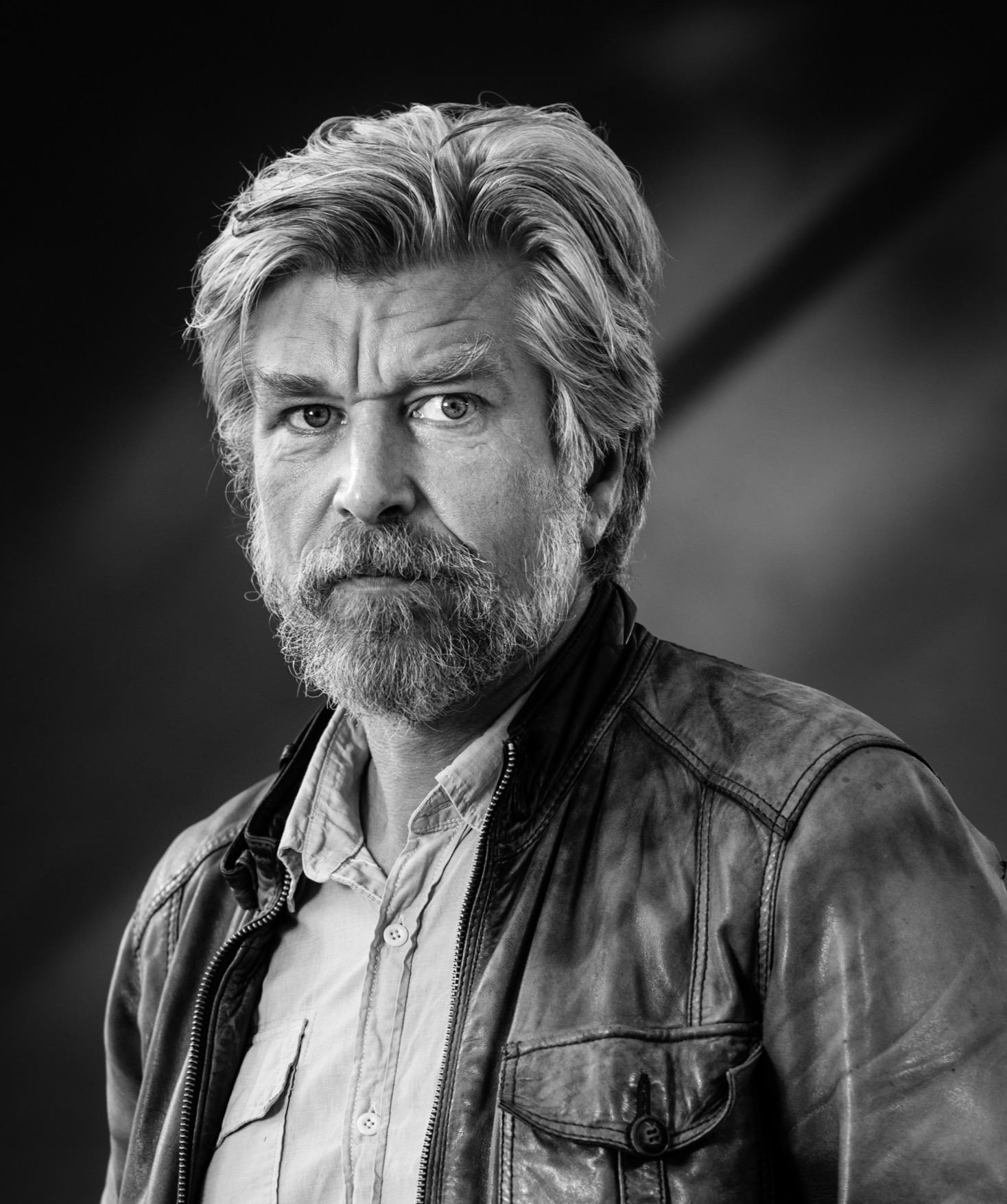

Triumph of the Will, the 1935 Nazi propaganda film directed by Leni Riefenstahl in Nuremberg, comes up twice in the final volume of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s six-volume autobiographical novel, My Struggle. Both mentions of the film occur in the midst of Knausgaard’s epic tangent on Hitler’s autobiography and the rise of National Socialism in Europe.

The first comes during a discussion of the conversion of Martin Heidegger and other German intellectuals to Nazism. Quoting a German journalist on how Nazism provided a “widespread feeling of deliverance, of liberation from democracy,” Knausgaard indicates the sense we can get of “this aspect of the Third Reich—the popular demonstrations, the torchlit parades, the songs, the sense of community, all of which were unconditional joys to anyone who participated—by watching Riefenstahl’s films of the Nuremberg Rally… where all these elements are present.” Precisely because Riefenstahl’s film was so meticulously staged, Knausgaard alleges, it is striking how its “content far eclipses the fact, because emotions are stronger than all analyses, and here the emotions are set free. This is not politics, but something beyond. And it is something good.”

Knausgaard does not mean “good” in the moral sense. He refers to the feelings of the people involved in the marches and parades. As he does throughout the four-hundred page section, Knausgaard attempts to reconstruct the thoughts and emotions of those who were attracted to National Socialism, under the principle that it is impossible to understand the emergence of Nazism—“the last major utopian movement in the west”—without understanding what moved the people of Germany, and later of other European countries, to embrace it. And what moved them, in Knausgaard’s view, was not the Nazis’ promise to redistribute income, or Hitler’s analysis of world affairs, or even, initially, their hatred of the Jews. What moved them was, rather, the joyful feeling of togetherness and community, of being able to transcend not only the fragmented democracy of the Weimar period but politics altogether.

“In National Socialism,” writes Knausgaard, “philosophy and politics come together at a point outside the language, and beyond the rational, where all complexity ceases, though not all depth.” Riefenstahl’s film communicates the pleasure the people experienced—how “good” it felt to them—at having escaped the quotidian chaos of their shabby republic and their trivial private lives, at being liberated from the restrictions of rationality and deliberation, at being on the brink of achieving something large and lasting, deep and simple.

A similar focus on the emotional wellsprings of Nazi politics is evident in an important but largely overlooked recent film, which opens with black and white footage from Triumph of the Will. At the beginning of Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life, we see—in lieu of opening credits—images of Hitler in the open cockpit of a plane descending through the mist as he lands for the rally in Nuremberg, Hitler standing before a teeming square of Nazis in neat lines, Hitler riding in his cavalcade through the streets. The film then shifts abruptly to the mountain town of Sankt Radegund, in the Austrian countryside, which appears at first to exist in total isolation from the opening tableau.

Against a backdrop of green hills and blue skies, we are introduced to Franz, a farmer and father, along with his mother, his wife, Fani, and their three young daughters. There are no military parades in Radegund, and, in the consciousness of the farmers, there seems to be hardly any politics. Fani’s and Franz’s lives are consumed by their faith, their work on the land, and their family. They live in what appears to be a fairytale innocence.

The fairytale ends when Fani is shown looking skyward, alarmed at the sound of planes buzzing overhead. The war has arrived, and Franz is soon sent to a training camp for the German army. At the military camp, Franz watches quizzically as the recruits are shown filmed images—projected on an outdoor screen—of Nazis marching victoriously through foreign cities in flames. But the propaganda has the opposite of the effect it is supposed to have on Franz. When he is called to fight again, Franz informs the recruiters that he won’t go. Later, he resolves not to serve Hitler in any way.

Based on the life and letters of Franz Jägerstätter, a farmer born in Radegund in 1907, later beatified by the Catholic Church, the character cites his faith in God and his love for Fani as his inspirations for refusing to do what everyone around him does without exception and, in most cases, without hesitation. When asked to articulate his reasons, he says little; when challenged with the fact that his resistance will “change nothing,” he merely nods. Offered a chance to avoid military service if only he will sign an oath of loyalty to Hitler, Franz refuses. He is taken from his wife, mother, and daughters, then imprisoned, tortured, and eventually executed. In Radegund, his family is outcast from the community and deprived of wartime rations.

Advertisement

Some critics of A Hidden Life have bemoaned the film’s lack of historical detail, pointing out that hardly anything is said about concentration camps or about the intricate political circumstances that prepared the way for Nazism. According to The New Yorker’s Richard Brody, Malick uses Nazi Germany “emblematically,” as a merely metaphorical backdrop to “illustrate the ultimate clash of good and evil, the ultimate price of resistance.” Likewise, The New York Times’s A.O. Scott lamented that Nazism is “depicted a bit abstractly, a matter of symbols and attitudes and stock images rather than specifically mobilized hatreds.” These criticisms not only miss Malick’s point, they invert it.

Malick, like Knausgaard, thematizes the “symbols and attitudes” of Nazism because he perceives how central these were to the appeal of Nazism itself. The film demonstrates impressionistically what Knausgaard, with his characteristic thoroughness, lays out in voluminous excerpts of diary entries and contemporaneous accounts from the period: the “goodness” of Nazism was as much about its symbols and attitudes as it was about its policies and actions. But the appeal A Hidden Life makes as an artistic experience is the opposite of symbolic. For the contemporary viewer, the film’s power flows from the fact that, whatever political and social convulsions led to the moment when Fani cranes her neck skyward, individual Germans like Franz and Fani were confronted by a choice that remains perfectly legible today.

Some at the time may not have felt Nazism to be a choice at all. History nevertheless records that there were, without any doubt, resisters. The existence of these resisters has “proved crucial to establishing a kind of ex post facto moral compass,” writes Rand Richards Cooper in Commonweal magazine, “reminding Germans—rather in the way that the witness of passionate nineteenth-century abolitionists reminds Americans regarding slavery—that a point of moral sanity was in fact visible to some, and thus available to all.”

How does Franz achieve this moral sanity? That is the central question of A Hidden Life, and it is in how he addresses it that Malick’s critics find special cause for complaint. Scott, at the end of his review, confesses that his incomprehension of Franz’s motives may be related to his personal preference for “historical and political insight over matters of art and spirit.” It is refreshing to hear a critic be so honest about their intellectual biases. It is also revealing of the assumptions that seem to pervade the broader discussion in recent years—carried on mostly by academics and op-ed writers, as opposed to artists—about the relationship between the politics of 1930s Europe and those of our own time. But what if the capacity to appreciate the relevance of Nazism to our own time is, in fact, inseparable from our willingness to attend seriously to “matters of art and spirit”?

Knausgaard finished his novel—and Malick likely started working on his film—well before Trump took office, so it is misleading to think of their artworks as “responses” to the events of the past four years. Nevertheless, and partly for that reason, they offer a useful vantage point from which we can evaluate not only our own relation to that past, but also the limitations of the intellectual tools we have tended to turn to when trying to articulate that relation.

Beginning not long after the 2016 election with the historian Timothy Snyder’s bestseller Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (2017), soon followed by the philosopher Jason Stanley’s How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them (2018), numerous scholars have sought to use historical analysis of the Weimar period to alert Americans to the early signs of fascistic rule. As the Trump presidency has dragged on, these urgent warnings have given way to a wide-ranging debate, including in these pages, about whether such historical analogies are warranted or appropriate.

Understood in relation to that debate, Malick’s and Knausgaard’s artistic treatments of Nazism may persuade us not of the inaccuracy or inappropriateness of such analogies, but of their utter and complete futility—at least insofar as it is claimed such comparisons can inoculate us against repetition. In their focus on the emotional pull of Nazism—its promise to liberate citizens from the frustrations and banalities of an alienated, lonely existence, to connect them with a mass of like-minded souls in “unconditional joy”—the works of Malick and Knausgaard expose us to aspects of how fascism works that it would be laughable to think could yield to academic analysis, no matter how accessibly arranged.

Advertisement

“Establish a private life,” warns Snyder. “Listen for dangerous words.” Do we really imagine it was advice such as this that interwar Germans lacked?

*

The second time Triumph of the Will comes up in Book Six of My Struggle, Knausgaard reflects that “Nazi Germany was the absolute state. It was the state its people could die for.”

Watching Riefenstahl’s film of the rallies in Nuremberg, its depiction of people almost paradisiac in its unambiguousness, converged upon the same thing, immersed in the symbols, the callings from the deepest pith of human life, that which has to do with birth and death, and with homeland and belonging, one finds it splendid and unbearable at the same time, though increasingly unbearable the more one watches, at least this was how I felt when I watched it one night this spring, and I wondered for a long time where that sense of the unbearable came from, the unease that accompanied these images of the German paradise, with its torches in the darkness, the intactness of its medieval city, its cheering crowds, its sun, and its banners… [and] I came to the conclusion… that it came… from something in the images themselves, the sense being that the world they displayed was an unbearable world.

Once again, the emphasis is on the affective allure of this “paradisiac” world, the pleasure that is involved in sublimating one’s individual will to the mythic collective. To make one feel justified in dying for one’s country is, in some sense, the greatest gift a country can bestow on an individual. And yet Knausgaard, watching the film as an adult in a liberal democracy more than seventy years later, finds it “unbearable.” What is it in this world—or, more precisely, in “these images” of it—that are so unbearable to Knausgaard?

One of the chief insights yielded by Knausgaard’s close reading of Mein Kampf is that Hitler, for all his vehement disgust with modernity, was “one of us.” He was modern and Western in the sense that he was secular yet wanted some larger meaning; modern and Western insofar as he craved something that the rationalized, bureaucratic nation-state is organized to exclude. To say that Knausgaard arrived at this insight by making an analogy between Hitler’s time and our own would be to miss its force, for the analogy presumes a distance requiring some leap of imagination—or historical scholarship—in order to bridge it. In fact, no such distance exists.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Knausgaard recounts, large portions of Western high society “closed the door” on religion, while millions were uprooted from their communities and traditions, often settling in overcrowded cities teeming with poverty, exploitation and, soon, militarism. If we can only clear our eyes of self-serving fantasies, Knausgaard believes, we will see that we are still living, spiritually if not quite synchronously, in that century, and that its problems are still our problems. Among the largest of these is how individuals cut off from religion and tradition can satisfy their craving for meaning and transcendence, how they may connect with that “deepest pith” of human life.

Knausgaard acknowledges the salience of this problem, and also the ugliness of the ways many modern societies have endeavored to solve it. His artistic project in My Struggle may be viewed, in one respect, as an argument for art, rather than politics, as the proper place to explore the transcendent. Throughout the six volumes, Knausgaard strives to make contact with the “inexhaustible” feelings—feelings he associates with experiences of joy, beauty, plenitude, ecstasy, and reverence—that he believes are suppressed in so much of modern, secular life. In Book Six, he emphasizes that these emotions are also at work in Riefenstahl’s film, and that they speak to some of the elemental forces that drove Nazi ideology. But whereas Riefenstahl intentionally blurs the line between aesthetic feelings and political ones, Knausgaard insists on the necessity of segregating them. In contrast to the undifferentiated masses that populate Riefenstahl’s “German paradise,” the responsible modern artist anchors their artistic vision in distinctive personal experience, which they invest with what Knausgaard calls “the inimitable tone of the particular.”

But even within art, Knausgaard argues, the Nazi experiment has had its effect. So complete was the catastrophe of Nazism that it warns us not only against the danger of utopianism in politics, but also against the danger of utopianism in any collective cultural endeavor, including art. Knausgaard laments the extent to which Western art after Nazism has been oriented toward ideas (the cerebral, the critical) rather than toward the emotions (the passionate, the inexpressible), but his novel, about the life of a bourgeois man raising his family, demonstrates that even he does not wish completely to disavow this orientation. Indeed, as many critics have noted, Knausgaard surrounds his musings on the transcendent with thousands of pages documenting a man making cereal, tidying his children’s bedrooms, checking his email, and agonizing over whether he should get off the couch to make another cup of tea.

The prosaicness of My Struggle is, in this light, an act of prudence and self-limitation: while expressing his perennial attraction to the “inexhaustible” emotions, Knausgaard never forgets their danger. The long digression on Hitler—the culmination of Knaugaard’s book-length Kampf against what he takes to be his own Hitlerian impulses—ends with Knausgaard’s remembering the moment he felt most powerfully the stirrings of the “we” he associates with fascism: in the aftermath of Anders Breivik’s summer camp mass shooting outside of Oslo in 2011.

This “we” emerged amid a moment of national mourning and grief, and yet Knausgaard still perceives in it the germ of a potentially fascist collectivity. Even sitting alone, as he writes the final portion of his book from his home office in Malmö, a medium-sized city in Sweden, where he lives with his wife and his (then) three children, Knausgaard recognizes in himself a desire he identifies with Nazism: to reach beyond the dull comforts and tedious complications of bourgeois democratic life. But he also knows something the Germans marching in Riefenstahl’s film did not know, and this thing compels him to resist this desire, as it relates to politics and even to art.

What makes Riefenstahl’s film unbearable to Knausgaard is that he knows the catastrophic endpoint of the joyful, torchlit parade. We might even say My Struggle in its entirety is an investigation of the liberal-democratic self—in its nobility as well as in its banality—that has been shaped by the knowledge of where Hitler’s parade of the “we” ends.

Malick, too, knows where this parade ends, yet he comes to a conclusion different from Knausgaard’s about how art might be meaningful after Auschwitz. In a review that chided the film for its “heavy-handed moralism,” the critic Lidija Haas observed that it was “hard to tell whether it’s an intentional irony” that Malick begins A Hidden Life by showing a “fantasia” of a mountain community that a “fascist would adore.” I don’t see anything ironic about it, but Malick’s romantic evocation of life in the mountains, in a movie that begins with footage from Riefenstahl, could hardly be accidental.

Before her Nazi period, Riefenstahl both starred in and directed a series of “mountain films” that were reputedly admired by Hitler. In these films, wrote Susan Sontag in her famous essay on fascist aesthetics, the “mountain is represented as both supremely beautiful and dangerous, that majestic force which invites the ultimate affirmation of and escape from the self.” A Hidden Life also makes use of a majestic romantic imagery: the mountains shrouded in mist form the backdrop for more than one scene in which a farmer is tilling the fields at dusk. That this imagery is deployed in a film devoted to resistance to Nazism, however, might inspire us to ask whether it is necessary—or wise—to abandon the field of the emotional sublime to the fascists.

Ever since Walter Benjamin observed, in the epilogue to his much-cited 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” that the logic of fascism was toward “the introduction of aesthetics into political life,” Western artists have gravitated toward one of two paths. Many leftwing artists, suspicious not only of the aestheticization of politics but of any emotional appeal not immediately assimilable to their political purposes, have taken part in a counterattack that culminates, as Benjamin predicted it would, in the full “politicization of art”—that is, the reduction of art to agitprop. Liberals and many conservative writers have, on the other hand, predominantly done as Knausgaard recommended and tried to sequester aesthetics within the artistic sphere, even there taking care not to let things get out of hand.

An appreciation of the full spiritual force of movements like Nazism might encourage us to countenance a third alternative, one that acknowledged the centrality of symbolism and emotion to political life, and deployed them against the eroticized collectivism that is so evident in Riefenstahl’s film. This aesthetics would honor the triumph, we might say, not of the collective will, that threatening “we,” but of the individual conscience.

Midway through A Hidden Life is an arresting tableau: Hitler, again in grainy film footage, appears in uniform, playing with a little boy on the viewing deck of his retreat in the Bavarian mountains, the sun glittering off the mountainside behind him. The interlude—beautiful but haunting (haunting because beautiful)—underscores, just as the film’s opening does, the aesthetic and emotional appeal of the Nazi project. Malick does not shrink from this appeal, but neither does he allow it to shrink his own ambition as an artist. In a film that begins with Riefenstahl’s footage, the very worst that can ensue from the politicization of such ambitions is in full view. But A Hidden Life rather than being intimidated into modesty by fascist art, presents a countervailing utopia to the völkisch collectivist one, holding out the prospect of a different kind of “escape from the self.”

It is not incidental to Franz’s story that, for him, religion is still an open door. Christianity provides both the substance and the inspiration for the orienting world “beyond” politics in A Hidden Life. Of course, as the film depicts, plenty of churchgoing Christians were among Nazism’s most enthusiastic supporters. And conversely, the aesthetic power of Malick’s late films, even as they have grown more explicitly Christian in their imagery and message, is perfectly accessible to many of us who are not Christians. Christianity, in these films, is one among many educators of the moral sentiments, one among many reminders that ethical action is not dependent on “historical and political insight” and often will remain unmoved by it. Art can be another such educator.

“I have this feeling,” Franz tells the Nazi judge who presides over his trial. “If God gives us free will, we’re responsible for what we do—or what we fail to do. I can’t do what I believe is wrong.” Franz’s belief, like the beliefs of the fascists, is based on a feeling. This why his “resistance” has seemed opaque to those more accustomed to researching and factchecking their way to virtue, but it is precisely what gives his story its relevance in a period in which a new emotional sincerity is spreading throughout our political life, often overpowering our liberal-democratic caution about political passions.

Yet, in contrast to the fascists, Franz does not clothe his moral feeling in self-certainty; still less does he attempt to transform it into dogmatic judgment. Rather, he accepts that his decision is vulnerable to counterarguments, including those that his wife and lawyer repeatedly put before him. He could be wrong, he acknowledges to the judge, but he cannot sign the oath. It is not only fascist feelings that are, sometimes, inexpressible.