Jerry Mitchell’s story reads like a treatment for an inspirational docudrama. A small-town boy in 1980s East Texas reads a dog-eared copy of All the President’s Men and decides he wants to spend his life doing investigative journalism. After a few post-college years working on regional newspapers in Arkansas, he lands a job at a leading Mississippi daily newspaper, The Clarion-Ledger, where he helps solve some the most notorious racial crimes of the twentieth century. (The publisher of The New York Review, Rea S. Hederman, is a former executive editor of The Clarion-Ledger.)

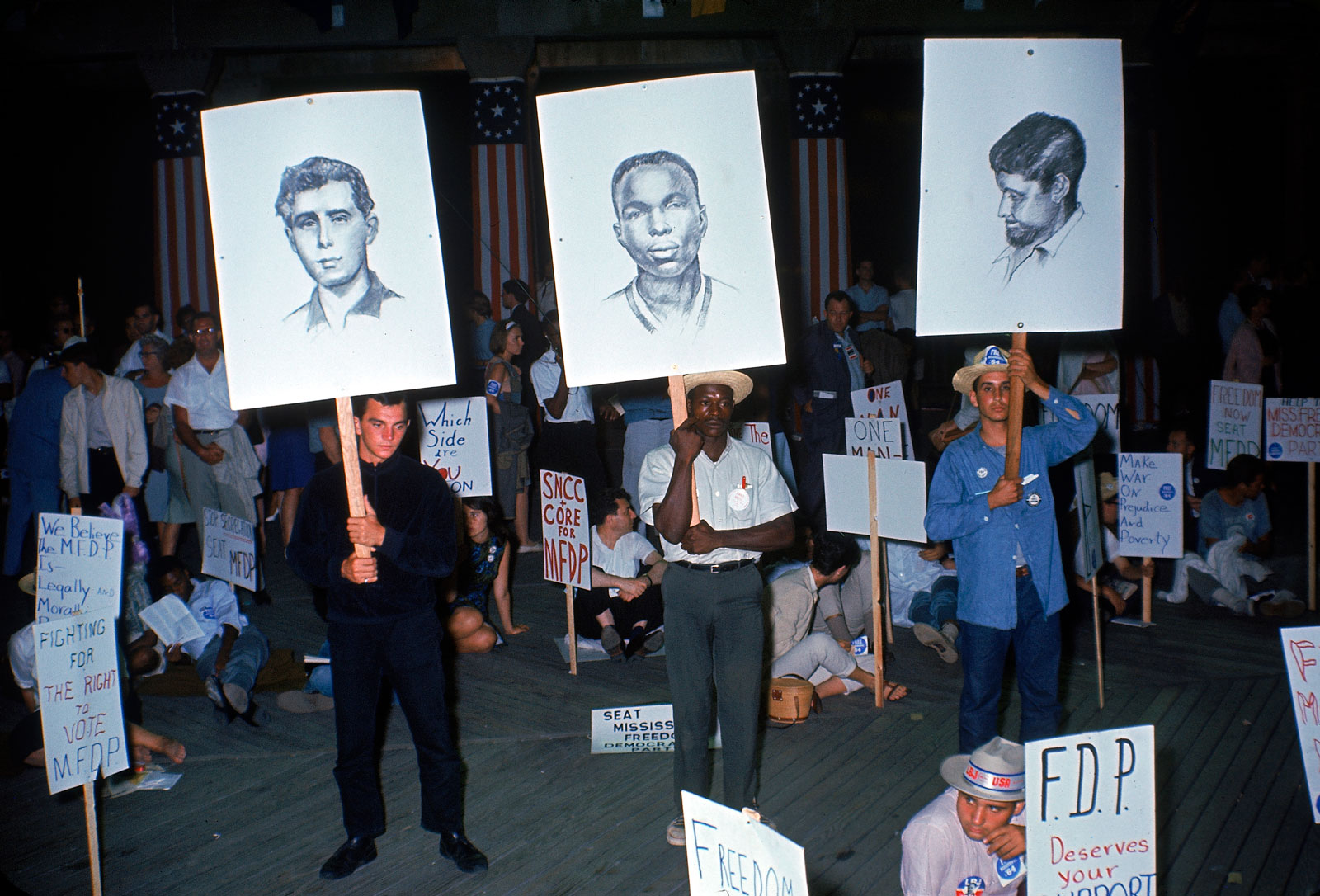

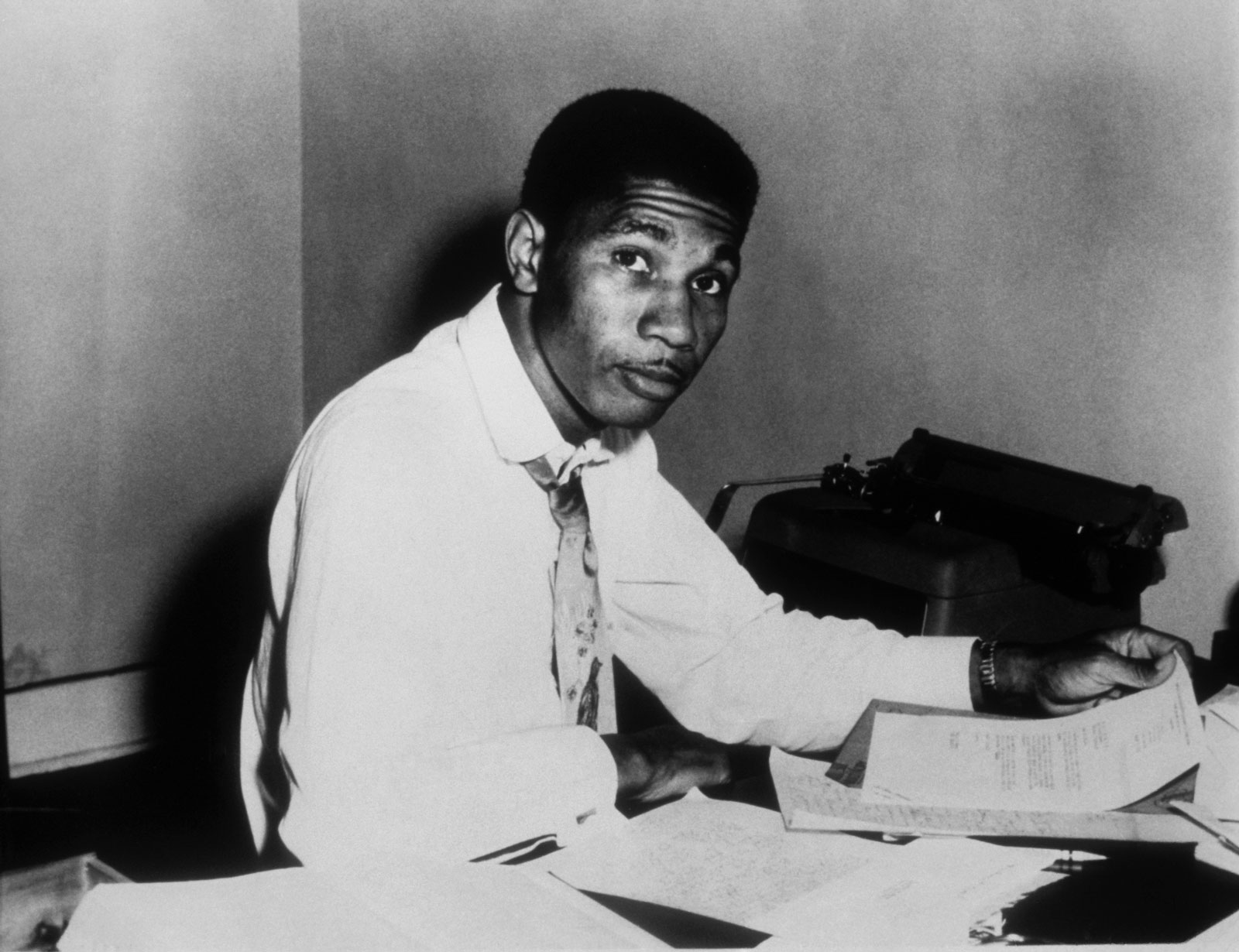

Among the murder cases that Mitchell investigated and got reopened were the 1963 assassination of Mississippi NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers, and the 1964 murders of civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner. Mitchell also uncovered new information that would prove central to the successful 2002 prosecution of Bobby Frank Cherry, one of the bombers of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four girls between the ages of eleven and fourteen.

For his work, Jerry Mitchell was nominated for the 2002 Pulitzer Prize, and in 2009, he received a MacArthur Foundation genius award. When Mitchell’s memoir, Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era, appeared earlier this year, The New York Times’s reviewer called it a “brave, bracing and instructive” book that “warrants praise, gratitude and a wide audience.”

I initially spoke to Mitchell in New York in February, then in further conversations by phone with him at his home in Mississippi. This is an edited and condensed version of our interviews.

Claudia Dreifus: In Race Against Time, you wrote about growing up in a place that was “something like” Mississippi. What did you mean by that?

Jerry Mitchell: Well, I grew up in East Texas, which is either the beginning of the South or the end of the South. It certainly wasn’t the Deep South. Once I got to Mississippi, in 1986, I learned the difference.

The N-word was something that had fallen out of polite conversation in Texas. When I moved to Mississippi, I started hearing it regularly, and not just from people who might be called rednecks. You heard it from people like judges. That shocked me.

What brought you to Mississippi in the first place?

A job. When I was twenty-two, Dave Kubissa hired me as a summer intern at my hometown paper, the Texarkana Gazette. He later became the editor of The Clarion-Ledger and offered me a job there. I became its court reporter.

How did you come to make the civil rights murders into your beat?

It was a series of circumstances that drew me into these cold cases. Mostly, I was outraged at the injustices I began to learn about. Specifically, that between 1954 and 1970, there had been more than a hundred and twenty civil rights–related killings in the US. About a third of them were in Mississippi. Very few even went to trial.

When did the idea of making these killings into the center of your work crystallize?

I’ll give you the exact date: January 10, 1989. I’d been at The Clarion-Ledger for less than three years. As court reporter, I’d been assigned to cover the press premiere of Mississippi Burning, a feature film loosely based on the 1964 murders of Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman.

Veterans of the civil rights movement despise that movie. They say it shows J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI as heroic and the local black citizens as cowering in fear—a huge inaccuracy.

You’re right. But for me, the movie was an eye-opener. I didn’t know much of the background. What I knew was that the murders were a landmark in American history. They were part of what helped eventually lead to the Voting Rights Act.

As part of the story, I talked with the two FBI agents, Roy K. Moore and Jim Ingram, who’d worked on the original investigation. They told me some of the backstory. They said there’d been more than twenty Klansmen involved and just about everyone in Mississippi knew their names. Yet the state wouldn’t bring murder charges against them. Finally, in 1967, the federal government charged them with conspiracy to violate the civil rights of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney.

After a trial, seven were convicted—and got off with light sentences. I couldn’t wrap my head around that: killers walking around free, and everyone knowing it, and winking and nodding. I thought, Let me see what I can dig up that could get some of these cases reopened.

How did you begin? Was it daunting?

I had done investigative work previously. I knew how to go about it. Initially, you ask, What documents still exist? Are there police reports? What’s in the court file? I’d look through newspaper clippings from the 1960s to find the names of witnesses or others who knew something about the crime. I’d try to locate them, or their descendants. Maybe someone had said something to relatives that would be a clue?

After assembling some preliminary information on different murders, I decided to put my efforts in two of the better-known cases. The Mississippi Burning case and the Medgar Evers assassination appeared to have the most promise. What I was looking for were cases with the most potential for being reopened.

Why were these two more promising than others?

Because, at least with them, you’d had trials, which meant there been investigations and there might be some records. With a lot of the cold cases, there’d been no trials, no arrests, no investigations.

With the Mississippi Burning case, the authorities seemed to have no interest in revisiting it. At least, not at first. So I always was working on two tracks: when I was stalled on the civil rights workers’ case, I turned my attention to the Evers assassination—where I had a few more leads. It would turn out that as I made progress on one case, it often led to new information on the other.

To give you some background on the Medgar Evers assassination: in 1964, a Klansman named Byron De La Beckwith was tried twice for the murder. Both times, he got hung juries and went free.

What I discovered in 1989 was that at the second Beckwith trial, the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission, a branch of the state government, had tried to get him acquitted by investigating potential jurors and giving that information to the defense. That was new information and it was key to eventually getting the case reopened.

What was the Mississippi State Sovereignty Commission exactly?

A secretive branch of the state government that spied on Mississippians in an effort to halt desegregation. They made files on people. It was sort of the Magnolia State version of the Stasi.

In February 1989, after the ACLU filed a lawsuit to open up the commission’s files, some of its records were accidentally made public. And in there was some surprising information relating to the murders of the three civil rights workers. It showed that in 1964, a spy had infiltrated the office of the main Mississippi civil rights coalition and stolen the application forms of the Freedom Summer volunteers. He [the spy] took them to the commission.

I then did a story showing how the state of Mississippi had spied on Rita and Mickey Schwerner in the months prior to his being killed. What I learned that was new was that the Sovereignty Commission had produced a report on the Schwerners and that this file was given to the police in Meridian, where the couple ran the local Freedom House.

In Meridian, probably half the police were in the Klan. This showed a direct connection between the Klan, the police, and the state.

After that break, there was another relating to the Medgar Evers murder. It turned out that the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission had actually aided Byron De La Beckwith with his defense when he was put on trial in 1964. That discovery was central to the Hinds County assistant district attorney’s reopening of the case, which led to Beckwith’s 1994 murder conviction.

Before that trial you went to Beckwith’s home and interviewed him. Why?

I want to talk to the killers. Always.

Were you surprised he was willing to see you?

No. I passed The Quiz.

What was that?

It was a long list of questions like: Where do you live? What are your parents’ names? Where do you go to church? I could’ve refused to answer them, but I knew he’d love my answers because I had a conservative southern WASP upbringing.

Once I got to his house, I asked the questions. When you’re talking to the killers, they may not give you a straight answer to “Did you do it?” But you want to see their reaction when you ask.

So you asked Beckwith if he’d shot Medgar Evers?

I did.

And what’d he say?

He said no. He blamed it on Lee Harvey Oswald. [Laughs.]

In Race Against Time, you wrote that you sometimes worked with law enforcement in your investigations of the cold cases. Should a reporter be doing that? Some people say it blurs the lines between the press and law enforcement.

Advertisement

I have a friend who, like me, is an investigative reporter and he wears a button that says, “I just catch ’em, I don’t fry ’em.” I like that. I’m exposing the injustice. I’m not the authorities. I’m not the jury.

But you did work with law enforcement, right?

Oh, yes: my goal was always to try to get these cases reopened.

Some I worked with more successfully than others. The Hinds County DA’s office, they loved me one minute and hated me the next. On the Medgar Evers case, they hated me when I discovered that the rifle used in the assassination had ended up in the gun collection of a local judge. On the other hand, they loved me when I had received from Myrlie Evers-Williams, the civil rights leader’s widow, her family’s copy of the court transcript from the second Beckwith trial.

With the Evers case, just about all the evidence, including the murder weapon, had disappeared from custody. You couldn’t have reopened the case without that transcript.

And I had a great relationship with Ben Herren, the FBI agent on the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing case. I also had a terrific relationship with the federal prosecutor there, Doug Jones. He’s now the senator from Alabama.

At one point, I was going to interview Bobby Cherry, one of the suspects who was living freely in Texas. I didn’t know the case very well. And they gave me a background briefing, saying that they believed Cherry had planted the bomb.

Herren has since told me they never would have been able to solve the Birmingham case if it hadn’t been for the press. I think that’s right. What happened was that Cherry held a press conference in Texas at which he proclaimed his innocence. His granddaughter saw it and said, “Wait a minute. He’s not innocent. He bragged about his involvement.”

When I did a story about the grand jury in Birmingham taking another look at the case, the Associated Press carried my report, and it was published across the country. In Montana, one of the ex-wives of Cherry read that. She drove more than two hundred miles to the nearest FBI office and told them something to the effect of “He told me he lit the fuse.”

The testimonies of Cherry’s ex-wife and his granddaughter were crucial to winning the Birmingham case. In 2002, thirty-nine years after the crime, this killer of children was finally convicted of murder. He died in prison—as did Byron De La Beckwith and Edgar Ray Killen, who’d organized the killing of the civil rights workers.

What’s the argument for having trials at such a late date? Is it the same as pursuing grizzled Nazi war criminals?

In many ways, it is. Sure, the punishment is late, but the families of these victims still want to see justice before they die. And when these trials occur, the families and the public learn what really happened. History is corrected.

After I started working on the Mississippi Burning case, we learned that Mickey Schwerner, one of the three, had been on a Klan death list. Sam Bowers, the imperial wizard, ordered it. So that was already in play when they were murdered. The order to kill always came through Bowers.

How many of the cold cases is Bowers linked to?

The White Knights of the KKK in Mississippi are linked to at least ten. If you count the Evers killing, it’s eleven.

They even killed their own. In the case of Robert Earl Hodges, he had just left the Klan, and Klansmen worried that he might talk to his son-in-law, a highway patrolman.

Do you think the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination was part of the Klan’s portfolio?

It’s a good question. The evidence obviously appears to point to James Earl Ray. A number of people believe he was set up. Who knows?

We can certainly say that the White Knights wanted King dead. There was a $100,000 bounty that the White Knights put on him, news of which got to the prison where Ray was and that he escaped from. There’s plenty of evidence that Ray pulled the trigger. He may have killed with the belief that the Klan or others would reward him.

I wouldn’t doubt there was some kind of conspiracy to kill King.

What links the civil rights–era murders to contemporary news events?

The dehumanization of the victims. That’s the same now as it was then. Once you dehumanize someone, you give yourself permission to harm them. When you see the eight-and-a-half-minute video of the murder of George Floyd, there isn’t a moment when Floyd’s humanity is recognized by the cop who killed him.

The other parallel is in the role of law enforcement in enabling or even committing these crimes. These days, you sometimes hear reports of white supremacist groups infiltrating police departments. Back in the 1960s, members of the KKK purposely joined police departments.

In the Mississippi Burning case, it was the Klan with the cooperation of law enforcement that did the killings and the cover-up. In fact, about a hundred law enforcement officers from Neshoba and Lauderdale counties were in the Klan. The Neshoba county sheriff, Lawrence Rainey, and his deputy, Cecil Price, were among those in 1967 tried with violating the civil rights of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.

The terrorism had a clear purpose: to restore and maintain white supremacy.

And today?

It’s the same thing. When I saw that video of the killing of Ahmaud Arbery, I felt sick: white men chasing down a young black man and killing him in cold blood. It reminded me of pre–Civil War slave patrols that gave any white man power over anyone of color.

Under Georgia law today, residents can arrest each other if they’ve witnessed a crime and the police are not around. The white men who killed Arbery hadn’t even witnessed a crime. Arbery was chased and killed by Gregory McMichael, a former police officer and a retired investigator for the DA’s office, and his son, Travis. A neighbor, William Bryan, videoed the killing.

McMicheal’s law enforcement background led two prosecutors to recuse themselves. The second said the killers could not be held responsible under Georgia law.

The thing I’ve learned from all my reporting on the 1960s is that impunity always leads to more crime. You saw this with the Klan. They would beat someone terribly, and law enforcement, which often had Klan members in it, would do nothing. Then, down the track, the same people killed someone. You saw that again and again.

You mentioned earlier that some present-day police departments have been infiltrated by white supremacists? Do you have proof of that?

There have been multiple recent reports of police posting racist materials on social media. Another source is a 2006 FBI report that was never made fully public. A redacted summary was released. It warned about white supremacists infiltrating law enforcement.

The report also warned about “ghost skins,” hate group members who don’t display those beliefs so that they can “covertly advance white supremacist causes.” This June, twenty-six members of Congress requested that the entire report be made public.

You’re no longer at The Clarion-Ledger, your home for three decades. Why did you leave?

I took a buy-out; I wanted to start a nonprofit, the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting, which seeks to ensure that investigative reporting stays alive in a state where it is desperately needed. We’ve just spent a year investigating prisons: we pointed out that if nothing was done, they would blow up. Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened, at the end of last year. Nine inmates died in a riot that was put down.

We’ve also reported on the historic lack of public education funding in Mississippi. I was curious how underfunded African-American schools were compared to schools for white kids. I couldn’t find figures for it. With some help from a mathematician, we were able to compare white schools to black schools between 1890 and 1960. The historical difference in allocation of funding was worth about $25 billion (at today’s prices).

H.L. Mencken once said that to be a journalist is to “live the life of kings.” Long ago, when you first read All the President’s Men and decided to become an investigative reporter, did you envision yourself living a king’s life?

I believe I have one of the best jobs in the world, but I don’t think of myself as a “king.”

I don’t generally talk about this much, but I am a person of faith. I do feel blessed in my work. Here’s how I think about it: people of faith and journalists should both be about seeking truth.

I personally feel that God wants justice. To me, it all fits together.