Wilfred Tebah collapsed on the cold linoleum floor of the Echo isolation ward of Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Pine Prairie detention center in central Louisiana on Wednesday, August 28, at 8 PM, screaming for help, unable to move his arms. After two weeks of refusing food and only drinking water from a fountain connected to the toilet bowl’s water supply, Tebah’s blood-sugar levels had dropped to a dangerous level and his blood pressure had shot up, putting him at risk of a stroke.

Because Hurricane Laura was battering the Louisiana coast, with high winds sweeping across the village of Pine Prairie inland, the facility’s doctor was absent, Tebah told me. Guards from GEO, the private corporation that runs Pine Prairie and other ICE detention centers across the country, rushed him to Savoy Medical Center in nearby Mamou. At Savoy, Tebah was handcuffed to a hospital bed as medical staff gave him two potassium tablets and poured glucose through three tubes into his mouth, stabilizing his blood sugar. Tebah said he was not conscious enough to give consent to being force-fed.

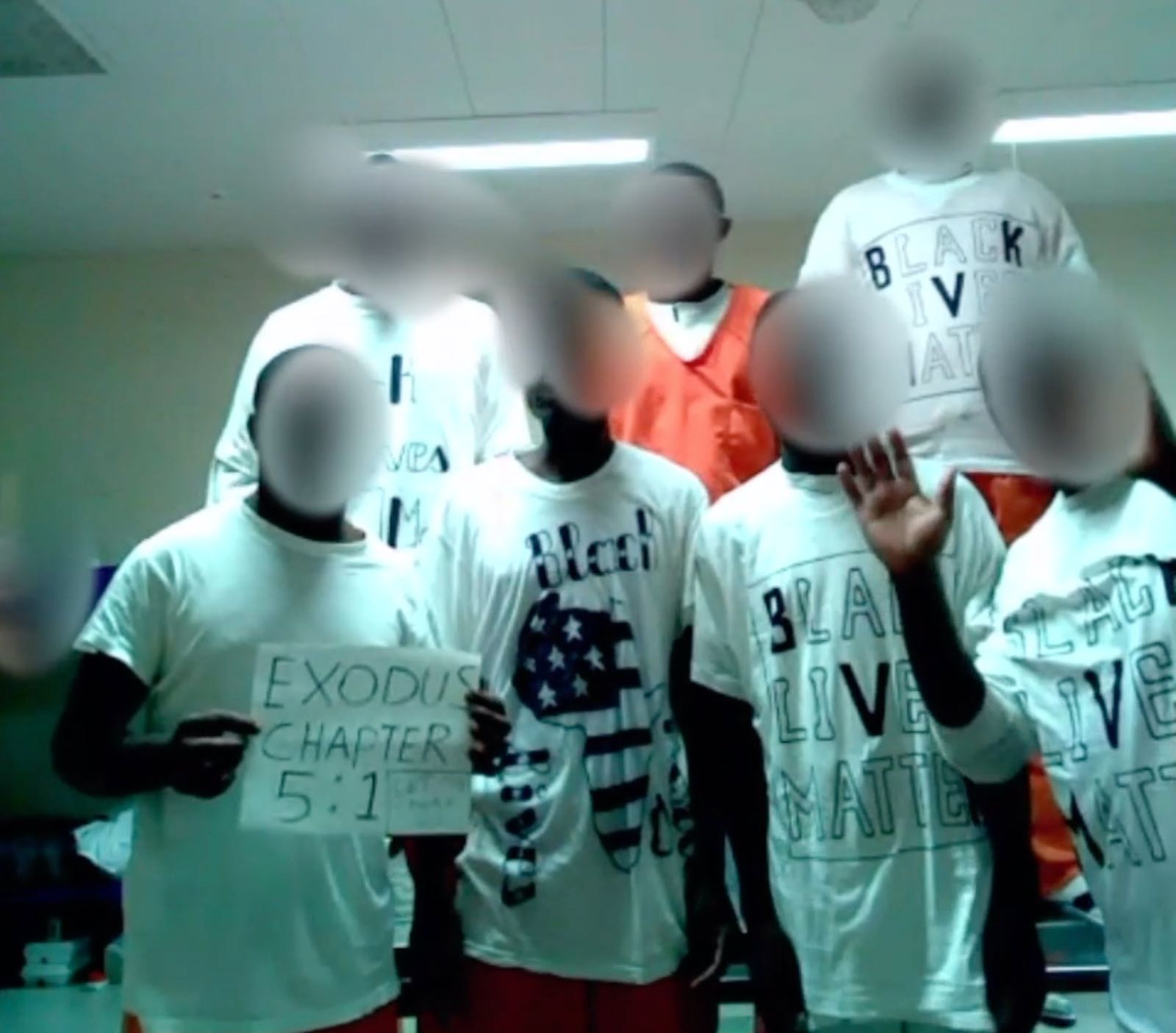

Over the last couple of years, Louisiana has become a national hub of immigrant detention, with eleven facilities that hold more than 15 percent of the total population in ICE custody. Normally, an average stay for an asylum-seeker held at Pine Prairie would be forty-five days, but the detentions of many of the African immigrants seeking refugee status now range from eleven months to two years. To protest these extraordinarily prolonged detentions, Tebah and forty-seven other African detainees began refusing food on August 10. Their hunger strike also aims to win redress for ICE’s failure to acknowledge their parole and bond applications, abysmal medical conditions, including a lack of Covid-19 precautions (even though several detainees are immuno-compromised), their being served food stuffs that have passed their expiration dates. Given these abuses, the strikers are demanding their immediate release.

It was back in February of this year that Tebah and forty-two other Cameroonian detainees at Pine Prairie first used hunger-strike tactics against what they termed “gross human rights violations” by ICE’s New Orleans regional field office and Judge W. Scott Laragy of the Oakdale Immigration Court. They were specifically protesting ICE’s refusal to acknowledge receipt of their parole and bond applications, their prolonged detention, and their lack of contact with any deportation officer. In addition, they alleged that Judge Laragy “dismisses almost all the evidence presented by us to support our cases,” and “often switches off audio records during hearings especially when he is going against the rule of law.” From 2014 through 2019, Judge Laragy denied more than 85 percent of the asylum cases he heard, a rate that is well above the national average (which is 63 percent). His office did not respond to a request for comment.

This first hunger strike lasted three weeks, ending “due to intimidation and pressure from ICE,” said Sylvie Bello, an immigration advocate who heads the Cameroon American Council. But then, only more months of inaction followed, and this, combined with deteriorating medical conditions at the facility, led another forty-plus detainees at Pine Prairie to declare another hunger strike. Though led by the Anglophone Cameroonians, this time they were joined by men from Uganda, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, Burkina Faso, and the Democratic Republic of Congo; the total number refusing food has fluctuated between forty-five and forty-eight, according to two detainees. When they announced the hunger strike by refusing their normal lunchtime meal in the cafeteria, guards blocked their exit and beat three of them, they told me.

Few advocates have taken up the detainees’ cause, but Rep. Ilhan Omar, Democrat of Minnesota, a vocal critic of ICE and the Trump administration’s immigration policies, said her office was helping them. “I am deeply concerned about the reports of bond and parole denial, physical abuse, and inadequate food for Cameroonian immigrants at the Pine Prairie detention center. We must call these actions what they are: human rights abuses, only the latest in a long line of dehumanizing tactics from the Trump administration, his Department of Justice, and ICE,” she told the Daily, noting that she is “currently working with my colleagues on legislative oversight on this case.”

In a statement sent to me via email on August 14, ICE denied the existence of a hunger strike. “Claims regarding an extended hunger strike by any group of detainees at the facility are baseless,” said southeastern region spokesperson Bryan D. Cox. It was true that some of the detainees had agreed to eat for a day as a condition of meeting with a senior ICE official regarding their case, but this blanket denial was a distortion. (In an episode of the Netflix series Immigration Nation, Cox is seen telling other ICE officials and members of the press that 91 percent of ICE arrests by one field office in 2018 involved criminals. When colleagues tell him those figures are false, he orders them to “own it.”) “ICE lies,” said Patrice Lawrence, co-director of UndocuBlack, an organization that provides services to undocumented Black people in the US.

Advertisement

On September 1, nearly three weeks into his hunger strike, Tebah—along with a few of the other hunger strikers with medical conditions—agreed to eat again. Others continued to strike, however, according to Tebah and Sylvie Bello. After Hurricane Laura damaged other facilities in the state, Tebah said that an additional two hundred or more detainees were transferred to Pine Prairie, putting them all at increased risk of Covid-19 infection.

Tebah, a twenty-five-year-old IT professional, is from the northwest province of Cameroon, an Anglophone region that since 2016 has seen a brutal civil war involving an armed insurgency against the Francophone-led government, a division that is a legacy of colonialism. According to the European Commission, the conflict has displaced more than 700,000 people; and according to the UNHCR, some 60,000 have been forced to flee to neighboring Nigeria.

In 2015, the European Union cracked down on undocumented migration to Europe from Africa, teaming up with the Libyan Coast Guard and the Nigerien military to prevent smugglers from transporting people across the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea. With the European routes closed, thousands of migrants then turned their sights on Ecuador and Brazil, to which they could get flights and visas, then make their way north overland to the US and Canada. In fall 2019, Tebah flew to Ecuador and journeyed across eight countries to ask for asylum at the Tijuana–San Ysidrio border crossing. He thus became one of about 10,000 Cameroonians to have fled their country for the US since 2016, according to Bello and Cameroonian-American immigration lawyer Pryde Ndingwan.

Tebah has been in the custody of Department of Homeland Security, which placed him in ICE’s Pine Prairie detention center, ever since October 11 last year. Along with the LaSalle and Alexandria detention facilities, also in Louisiana, Pine Prairie is notorious among immigration advocates for its mistreatment of Black immigrants.

“The truth is that what Black detainees undergo, what African detainees undergo, seems to be harsher than any other detainees,” Lawrence told me. “If they have any other intersection, if they are Muslim, or if they are queer, they receive harsher penalties from ICE.” Black immigrants face longer detention time, higher bond prices, higher chances of deportation, and more solitary confinement than any other group, according to Texas-based advocacy group RAICES. And besides the Africans, 44 percent of migrant families in detention nationwide are Haitian.

The modern history of immigration detention and deportations is the product of both Democratic and Republican administrations. In a 2018 report from the Center for Migration Studies, its director, Donald Kerwin, wrote that the Clinton administration’s 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act “eroded the rule of law by eliminating due process from the overwhelming majority of removal cases, curtailing equitable relief from removal, mandating detention (without individualized custody determinations) for broad swaths of those facing deportation, and erecting insurmountable, technical roadblocks to asylum.” The Obama administration deported 2.5 million people, significantly more than any other in American history.

The Trump administration has been especially punitive, with added racial animus against Black asylum-seekers, ending Temporary Protected Status for 59,000 Haitian immigrants, and shutting down the program entirely for El Salvador, Honduras, Sudan, South Sudan, Somalia, and other countries. Although that decision is still being fought in court, it has had devastating consequences for Haitian, African, and Afro-Latinx communities in the US. The Trump administration’s Muslim travel ban initially applied to two African countries, and was expanded in January of this year to include Nigeria, Eritrea, Sudan, and Tanzania—in total placing travel restrictions on more than 336 million Africans, or roughly 25 percent of the continent’s population.

The administration’s policy of keeping as many asylum-seekers as possible in Mexico during their immigration hearings, known as “metering,” has led to hundreds of Africans camping on the US–Mexico border in tent cities under the thumb of corrupt officials. American pressure on Mexico to tighten measures against migration across its territory has trapped thousands more Africans and Haitians in Tapachula, next to the Mexico–Guatemala border.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration has increased the average number of immigrants held in detention before the pandemic to about 50,000 from roughly 30,000 under Obama. (As of September 3, there were 20,713 immigrants detained, reflecting a reduction in numbers because of the pandemic.) In addition, ICE has been deporting Africans to unknown third countries during the pandemic, saying that it can’t reveal the third countries for security reasons. It has taken advantage of Covid-19 guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to justify a complete halt to processing new asylum cases during the pandemic; at the same time, the agency has been running near-weekly charter flight deportations to Haiti, according to Guerline Jozef, the president of Haitian Bridge Alliance, an advocacy organization that provides legal aid to Black migrants.

Advertisement

In July, the Associated Press revealed that “the Trump administration is detaining immigrant children as young as 1 in hotels, sometimes for weeks, before deporting them to their home countries under policies that have effectively shut down the nation’s asylum system during the coronavirus pandemic.” The use of hotels to separate children from their parents attracted attention because of the brazen use of the pandemic to circumvent child-trafficking laws. But the report did not mention the nationality or race of the children. “Nobody knew they were Black, so they just assume that if an immigrant family is being held in those places, they are Central Americans,” Jozef said. “But the reality is every single one of those families were Black families from Haiti.”

There are only a handful of legal aid groups catering to Black immigrants, and they are often underfunded and overstretched. Few Black immigrants are able to employ attorneys that greatly increase their chances of obtaining asylum. “The majority of Black immigrants do not have access to representation,” said Jozef. “Everyone is playing a part in the invisibility of Black immigrants. If they are invisible, their stories are not told.”

Louisiana’s Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards, and Rep. Garret Graves, a Republican who represents Pine Prairie’s congressional district, have thus far not returned calls and emails from activists regarding the hunger strikers. Cedric Richmond, a Democratic representative from a neighboring congressional district, sent a letter in July to ICE requesting a review of the cases of eight Cameroonian detainees in Pine Prairie, but the agency has not replied, Richmond’s spokesperson, Jalina Porter, told me. Immigration advocates say they want the Congressional Black Caucus to advocate for Black immigrants the way other caucuses do for the groups they represent. “We need more from the CBC,” said Sylvie Bello. “We need more from Cedric Richmond, from Karen Bass, from Yvette Clarke, from Hakeem Jeffries.” The caucus’s chairperson, Rep. Bass, Democrat of California, did not respond to requests for comment for this article.

Pushback by advocates has resulted in a few wins. Last December, Congress passed a provision called Liberian Refugee Immigration Fairness, which provides a pathway to green cards “for certain Liberian nationals and their spouses.” But as of August 31, by which date some two thousand Liberian-Americans had applied under the program, the immigration service had “given green cards to exactly zero people,” according to Lawrence. Many advocates view the Trump administration’s measures to freeze asylum and deport Africans, Haitians, and Afro-Latinos as a comprehensive effort to halt Black immigration to the US.

The African detainees at Pine Prairie are demanding an end to the abusive conditions highlighted in their protest videos. “We are like slaves, and the master is ICE,” one detainee told me. “We are begging you to help us in here. We are dying, for real.”