Every August, the public library in my hometown of Blue Hill, Maine holds a wet paint auction. Local artists, some seasoned, some aspiring, go out in the early morning to find their subjects: the dawn on the mudflats; blue islands slouching across the horizon; the nostalgic white pentagon of the post office. In the afternoon, seasonal residents linger in the Biography section with plastic cups of wine, bidding on studies of water and sky to add to their collections. The landscape of Maine—glacially gouged, furred with pines—precludes other muses, offering up endless variations on its theme with every change of the light, season, and tide. It is relentlessly consumed, reproduced, and sold, albeit in a less extractive way than the mining and lumber industries once used it. The art economy and its bedfellow, tourism, have made nature more valuable unspoiled.

Of course, it’s difficult to capture the natural splendor of an ageless place in ways that are surprising and new, especially in Maine, where there is so much tradition preserved in the buildings, the jobs people work, and the people themselves. “The place always reminds one of some abstract pictorial representation of itself,” wrote critic and novelist Elizabeth Hardwick, who summered down the road in the old port town of Castine. “Every little inlet, with its empty boat, the mast standing watch, is an illustration from a bad book.”

Hardwick spent the colder seasons in Manhattan. None are more to blame for the clichés of Maine art than New York’s creative class, which has long found refuge from “the hurly burly” of the city, as modernist artist John Marin wrote to his gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, in rural Maine. It was a place to live cheaply, with vistas everywhere on which to riff and hone one’s technique. Robert Henri, teaching a radical form of realist painting at the Art Students League of New York, brought George Bellows, Randall Davey, and Rockwell Kent to Monhegan Island to study the motion of crashing waves with kinetic brushstrokes; Kent found in Maine “enough for me, enough for all my fellow artists, for all of us who sought ‘material’ for art.” After World War II, the state became an important stage for American modernism and the craft movement.

The Farnsworth Museum in Rockland has recently published a catalog, Maine and American Art, that plumbs themes of identity and place through works in its collection, timed to coincide with the state’s bicentennial. The region has been a fertile place for art-making since long before European colonists arrived, and the essays in the Farnsworth catalog make frequent mention of the Wabanaki tribes and allude to the Red Paint People, whose fine stone adzes and sculpture have been excavated along the coast—allusions that serve to expose the perspective of the rusticator, tourist, itinerant, and the idealist in the art that we associate with Maine.

One of the earliest Maine landscape paintings is deeply impressed on my mind: a reproduction of Jonathan Fisher’s A Morning View of Blue Hill Village (1824) was hung in the basement of the congregational church where I babysat during Sunday service. In it, two women gaze over an orderly town, while a villager nearby beats away a snake. The forest had been cleared for timber and pasture (it has since returned), and the region’s allure was of raw material to be shaped, though even a subsistence life there was difficult. Fisher, a young Harvard graduate with skills as an architect and linguist, had sailed to Blue Hill to serve as its pastor in 1795. He tried to mold the small port town after his own Calvinist ideals (as well as his aesthetic sensibilities—he designed much of the town) and his repudiation of the industrialism that was sweeping Massachusetts.

Maine has continued to be a destination for escape and renewal. For many, it is the end of the road, a promise of semiretirement that has given even well-established artists the space to make what has turned out to be their best work. Winslow Homer moved to Maine late in life to care for his father, spending the rest of his career painting the sea in all its moods; the starched, cheerful beachgoers that populated his earlier work were succeeded by castaways and rain-spattered fishermen’s wives. Berenice Abbott followed US Route 1 from Key West all the way to Fort Kent, documenting America in the year 1954. She returned to Maine in 1966 to live, first in an old inn and then in a cabin in Monson on the fringe of the Great North Woods, where she photographed logjams, tractors, wharves piled with line and lobster traps, and the people who worked them.

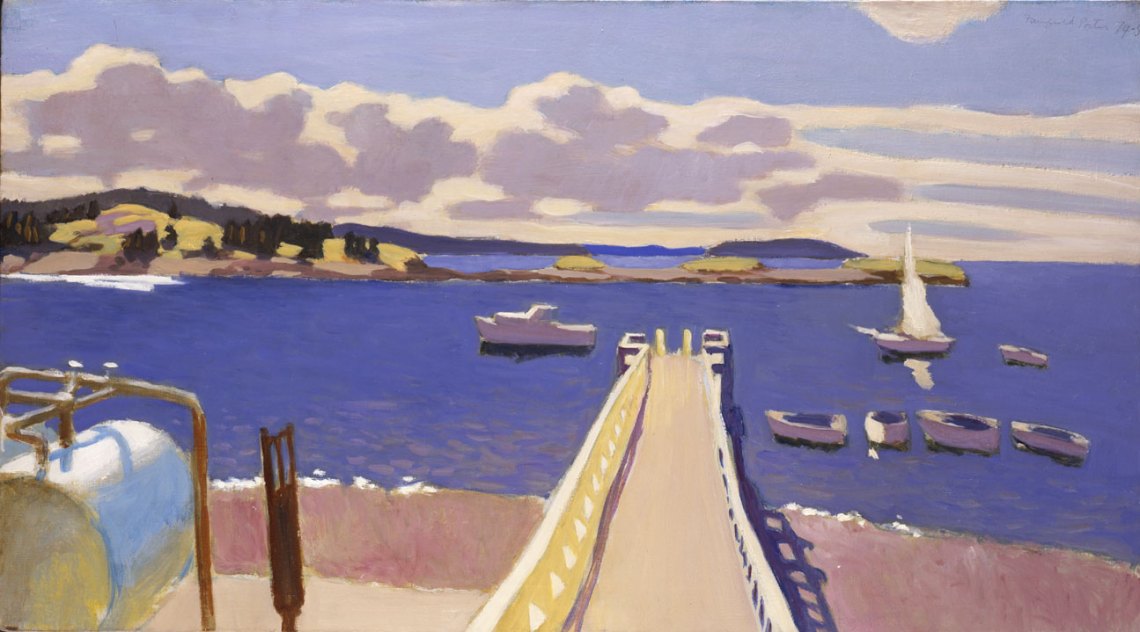

Abbott was on the lookout for a different Maine than depicted by the painters of vacationland: Frank Weston Benson’s white-clad daughters, in Impressionist style, reclining on sun-dappled hillsides; the August heat and idleness of Fairfield Porter’s flat, domestic vignettes populated by people in chinos and lawn chairs. In Maine, more than other places, physical setting is expected to work itself on the human soul, and the mossy hikes, numbing swims, and other repetitive activities of vacation are a part of the artist’s labor. For those who preferred to build character through voluntary hardship, Maine supplied more than enough of that “material,” too; John Marin, with no fashionable summer house in the family, holed up in decidedly uncomfortable digs on a spit of granite in West Point. He described his Maine as “one fierce, relentless, cruel, beautiful, fascinating, hellish, and other ish’es, place” (in thirty-eight years, he did not attempt the winter), and he rendered the convolutions of the coast in the same chaotic Cubist style that he did the hurly-burly cityscapes he had fled. Edward Hopper had an eye not for natural beauty but for abandoned houses and industrial shipyards, which he soaked in chilly blue shadows.

I grew up attuned to the strange contradictions of life in the rural yet cosmopolitan towns of Down East Maine, studded with galleries, where well-known writers, following Thoreau and E. B. White, hide out in old farmhouses (an article in the Travel section of The New York Times laughably compared a local seafood dive to The Algonquin Hotel) and where a local farmer has ceramics in the Smithsonian. I was also keenly aware of the politics of “nativeness,” as Marsden Hartley, who was born in Lewiston, put it: the possessive tensions between locals and summer people, the subtler but no less potent distinctions between generations-long residents, back-to-the-landers, and green suburban transplants like my family. These tensions twanged painfully this spring and summer, when small communities braced for moneyed refugees from New York and other hubs of contagion. Artists from away have always had to contend with their outsider status by making some bid for authenticity. Kent, fresh from Columbia’s architecture school, elected to work as a carpenter, lobsterman, and day laborer, clearly wanting to embrace the rugged qualities he admired in the locals of Monhegan.

Artists enabled a transformation of Maine’s coastal economies from subsistence to tourism, a legacy of gentrification that the Farnsworth catalog grapples with in part through the story of the Olson House, made famous by Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World. Over decades, Wyeth painted the Olsons, a poor brother and disabled sister who worked a saltwater farm in Cushing, often letting features of their dilapidated farmhouse—in Alvaro and Christina, a weathered door and an old bucket—stand for its inhabitants. When Christina died, the house, its likeness hanging in the Museum of Modern Art, was bought by the Hollywood producer Joseph Levine, who renovated it with the intention of displaying his personal Wyeth collection there. The small town’s residents resented the influx of tourism and publicity; the house became the object of an awkward legal dispute between the Levines and the state of Maine, and in the end it was purchased by the CEO of Apple, who donated it to the Farnsworth in 1991.

At First Light, a book of photography by Walter Smalling Jr. of artists’ houses and studios in Maine, is a sort of companion to the Farnsworth catalog. Short essays further explore the sense of place that drew artists and permeated their work. The houses tell stories all their own. Many were custom-built, fashioned after their occupants’ notions of New England life. Fisher painted his house yellow with ochre dug on his property and insisted on keeping his family busy with the production of hats and textiles. Homer’s house in Prouts Neck was like a ship, paneled inside with polished boards, with a cantilevered balcony from which to watch the sun rise over the sea. Lois Dodd and Frank Weston Benson both painted the landscape onto the interior walls of their homes.

In towns where little is developed and nothing is demolished, houses are passed down, repurposed, saved, haunted, and serve as material links between generations of artists. The cape house that Rockwell Kent built for his mother on Monhegan is now owned by the artist Jamie Wyeth, son of Andrew, who doesn’t live there but lives in a lighthouse, having said that “to live in a lighthouse is the quintessence of Maine.” Robert Indiana was seduced by an Odd Fellows hall in Vinalhaven, situated across the road from a house where Hartley had summered in 1938. This coincidence inspired the Hartley Elegies, a series of serigraph prints after the military symbols Hartley painted in Berlin for his fallen soldier lover. Indiana inscribed his tributes with the towns Hartley had lived in: Lewiston, New York, Berlin, Ellsworth, Vinalhaven—a circuit beginning and ending in Maine. Hartley wrote that his “native hills” had gone with him to Paris, Berlin, and Provence.

Advertisement

It would have been fascinating to see what remains of Louise Nevelson’s childhood home in Rockland. As a Jewish immigrant, the daughter of a lumber merchant and woodworker, she had a more ambivalent relationship to the state and its quaint architecture. Knowing that the only way to make a name for herself as an artist was to escape her small town, she made a calculated marriage to a Wall Street businessman and moved to New York. It’s impossible to look at the white assemblages of Dawn’s Wedding Feast (1959) without seeing the dismantled houses in their salvaged banisters, clapboards, and molding. (The Farnsworth has one column of the installation which, like Nevelson’s marriage, did not remain intact.) Though she bestowed much of her early work on the Farnsworth, Rockland has claimed her with much more enthusiasm than she ever claimed it.

Artists who did make their permanent home in Maine chose a degree of professional obscurity, and they risked being pigeonholed as regionalists or merely craftspeople. Bernard Langlais retreated to Cushing after his totemic wooden sculptures of farm animals were dismissed as folk art in New York (his delightful parody of his neighbor Wyeth, a wooden Christina with pink sleeves like lobster buoys, seems to critique the rustic flavor of art that is palatable to urban audiences). The Passamaquoddy artist Molly Neptune Parker, who died in June, spent her life weaving traditional baskets from the wood of the ash tree, a craft that has helped her tribe to survive economically and culturally in the face of assimilation.

Lengthy passages on shipbuilding aside, craft is largely neglected in the Farnsworth’s narrative of art in Maine. The vibrancy of Maine’s art scene is supported by traditions of apprenticeship and collective making, and by the postwar studio craft movement. Less well-known than Skowhegan School of Art and Sculpture, where artists like Lois Dodd, Alex Katz, and David Driskell came to develop a voice at a far remove from the conventions of academia, the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts was founded in 1950 to provide a space for artists to learn new mediums from one another—producing fewer great works than inspired forays, collaborations, and digressions. (The school’s early history is the subject of a recent book, In the Vanguard, which accompanied an exhibition at the Portland Museum of Art last summer.) Its campus on Deer Isle was where my grandmothers, one a ceramicist and the other a sculptor, distanced themselves from confining marriages and experimented with fiber and photography. It was where I learned to smith iron and silver, dye textiles, throw pots, and silkscreen—skills that were not merely hobbies but avenues for a livelihood that seems far more possible and rewarding there than in the most creative circles in Brooklyn, where the things one makes always beg for justification in the form of money or publicity. I learned letterpress from a former MPDC policeman who carted a trio of antique news presses into the woods to set poetry and Thomas Merton quotes; I know a young couple who stopped heating their home in the dead of winter in order to reserve firewood to stoke the kiln.

It was only after training abroad in Paris and Berlin that Marsden Hartley embraced the subject matter of his home state and established himself as “the painter from Maine” in an essay, “On the Subject of Nativeness.” The “opulent rigidity” and the “stout substance and texture” that he admired in the landscape and its people were embodied in the thick lines with which he rendered clouds, boulders dropped by glaciers, and the biceps of fishermen. His brooding paintings of Mount Katahdin—the Farnsworth has an early study, Song of Winter No. 6 (1908–1909)—the Down East coast, and the stormy gulf were contributions to what he suggested was a collective, continuing effort that ultimately dispensed with borders or provenance:

When the picture makers with nature as their subject get closer than they have for some time been, there will naturally be better pictures of nature, and who more than Nature will be surprised, and perhaps more delighted?

It’s a more generous way to read the work at the library auction, and one I’m more inclined to than Hardwick’s exasperated snark. When I picture Maine—where I no longer live, having myself absconded to the city—I see it through the dark, rich oils of Blue Hill mountain by the pastor’s wife, and the witty but tender portraits of the Christmas tree farm and seafood shack by the waitress who gave me drawing lessons. The personal and the specific are the antidotes to cliché, but these are often only recognizable to those who know a place intimately, and see, in every little inlet, home.