One spring morning, on a return visit to Iran in 2015, I was sitting in a taxi stuck in traffic in Tehran’s Towhid Square and scanning the image-plastered dashboard to kill time. I took in the familiar snapshots: Los Angeles singers like Dariush and Ebi, scantily clad Bollywood actresses, framed verses from Qur’an swinging underneath the rear mirror, and an amulet dangling from its little frame. But amid this collage, there was also a photo of someone I had never seen before: a severe but distinguished-looking uniformed man. I pointed to the picture, and spoke.

“Do you like Soleimani?” I asked the taxi driver.

“Oh, of course,” he said. “He’s my man.” Then, seeing the confusion on my face, he added, “I hate mullahs as much as anyone, believe me. But Hajj Qassem is different.”

It was after that encounter that I began to notice how ubiquitous the image of Soleimani, a man whose name few people had known just a few years earlier, had become. In the windows of corner stores, on top of car trunks and van doors—posters of him were everywhere. Just like my cab driver, ordinary people had begun to revere him despite his steadfast loyalty to the system so many of them despised.

To urban liberals like me, this widespread adoration of Qassem Soleimani was baffling. He had never wavered in his commitment to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, and the Quds Force, the elite unit of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) under Soleimani’s command, had proved vital to propping up Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Soleimani’s surge in popularity after the Iranian intervention in Syria was also connected with the prevailing belief that it was he who had defeated ISIS. Without Hajj Qassem, according to conventional wisdom in Iran, that army of evil would have overrun the borders of Iraq and attacked Iran itself, raping women, enslaving children, and staging public beheadings. Soleimani had saved the nation.

Finally, as if Soleimani hadn’t been romanticized enough, the US military, at President Trump’s behest, assassinated him by drone strike on January 3, 2020, in a fashion that happened to neatly align with Shia martyrdom mythology: the central narrative of the holy day of Ashura involves a mighty power shedding the blood of a heroic underdog in a cowardly fashion.

Iranian officials were swift to launch a campaign integrating the loss of Soleimani into their daily political messaging. The campaign began immediately after Soleimani’s killing, and it remains in full force today. His face is everywhere, writ large and small on billboards and on walls, on posters and in graffiti, on paper and on screens.

This commemoration of Soleimani as the ultimate martyr is the latest manifestation of the Islamic Republic’s long history of communicating political messages in graphic media—a particular cultural tradition of propaganda. It is no overstatement to say that an understanding of Iranian politics today rests on the knowledge of the part murals have played ever since the regime came to power in 1979.

The first face of the revolution to become its leading icon was, of course, not a soldier but a cleric. “There were colored photographs of the Ayatollah Khomeini,” noted V.S. Naipaul in the travelogue of his first visit to Iran in that momentous year (published in The Atlantic in 1981), “as hard-eyed and sensual and unreliable and roguish-looking as any enemy might have portrayed him.” Naipaul got many things wrong about Iran at the dawn of the revolution, but there was something in this observation that was spot-on. Khomeini looked hostile. He never smiled. His piercing eyes, set deeply in his haggard face under a heavy black turban, stared belligerently at the camera. The mistrustful glare conveyed a clear message: I am watching you.

I was a child in the Eighties, and my memories of that decade almost all have an image of Khomeini embedded in them. His face was plastered on every empty wall in my hometown of Ahvaz, on our TV screens, even on the first page of our textbooks at school, and later on, after his death, on all bill denominations. The ubiquity of his likeness spoke absolute power.

Murals were a crucial element of Khomeini’s propaganda machine, particularly during the Iran–Iraq War. Some of those war murals can still be found on walls in Tehran and in other cities. They followed a simple template, involving a portrait of Khomeini accompanying wartime martyrs, innocent-looking young men, highlighting both their sacrifice and their complete devotion to the leader.

via Amir Ahmadi Arian

An Iran–Iraq war mural: the young man is holding a Kalashnikov, a picture of Khomeini attached to its barrel. His headband bears the nickname of Abolfazl, Imam Hossein’s half-brother, who sacrificed his life on the holy day of Ashura to bring water from Euphrates to his brother’s camp. The man is sitting against the backdrop of a tulip prairie, the flower that symbolizes martyrdom in Shiism.

Advertisement

Mural artists essentially functioned as morgue masters: they took photographs of dead soldiers, sanitized the blood and gore, and refigured them as celestial beings taken up into the embrace of the divine—a technique Hamed Yousefi showed in his 2013 documentary, Sanat-e Farhang-Jang (The culture industry of war).

With the death of Ayatollah Khomeini and the end of the war, which came within a year of each other, the ideological zeal that had engulfed the country in the immediate post-revolutionary period soon abated. The discourse shifted from martyrdom to managerialism: suits replaced uniforms, beards were trimmed short, battlefield commanders gave way to engineers. Women still had to wear full hijab, but they moved from support work behind the frontlines to jobs behind desks. Over the course of the Nineties, under presidents Akbar Rafsanjani and then Mohammad Khatami, only distant echoes of the tendentious ideology of the previous decade were heard.

This dramatic shift, reflected in the visual culture of the time, was clearly evident in newer public murals. The portraits of Khomeini and the martyrs lost their monopoly on city walls. A relatively obscure branch of Tehran’s municipal government known as the Institute for Urban Beautification (also known as the Beautification Organization of Tehran) gained prominence. It favored colorful, somewhat kitschy work often with themes from nature or inspired by the love stories of classical Persian poetry.

An artist named Mehdi Ghadyanloo was particularly influential in changing the visual landscape of the capital in the early 2000s. A student of fine arts at the University of Tehran, Ghadyanloo responded to the call from the city authorities for a competition to decorate the thousands of empty walls in the city. He won the prize and got to work. Equally indebted to the surrealism of René Magritte and the Pop Art style of David Hockney, Ghadyanloo manipulated perspective to create fantastical but highly rendered scenes: in his murals, cars fly and people walk upside down, gigantic balloons soar through illusory ceilings, and vast voids fill flat surfaces, usually against the background of a pristine blue sky.

Unexpectedly popular, his murals soon became an intrinsic part of the urban landscape, reflecting his optimistic vision of a livable Tehran. Ghadyanloo carefully skirted politics. His images are soothing backdrops, offering a whimsical utopia amid the chaotic metropolis.

Official ideology never disappeared from public spaces, except that Khomeini’s face was replaced by that of his successor, Ali Khamenei. But the fanciful and the doctrinaire coexisted on the walls of Tehran—until Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf became mayor. This former commander in the IRGC turned police chief went on to hold the office for twelve years. (Earlier this year, he became speaker of parliament, a testament to the closed shop of political power in Iran.)

At the time he was first elected, in 2005, the city was undergoing major changes. A decades-long expansion of the city has seen a large portion of its population relocated to far-flung suburbs, and enormous, endless expressways now slice through the urban fabric. Tehran now feels increasingly hostile to pedestrians and most Tehranis spend hours commuting in cars, seeing the outside world in fleeting flashes. As a result, the old neighborhoods’ wall paintings have lost their former visibility and relevance.

This car-centered urban sprawl has ushered in the billboard era. Large vinyl surfaces mounted on thick columns, enabled by new printing technologies, have replaced painted walls. Overly excited at the creative possibilities, the Institute for Urban Beautification went in for extravagant experiments, like its 2015 billboard gallery of modern art that displayed gigantic reproductions of works by Kandinsky, Pissarro, and other Western artists for ten days on more than a thousand billboards in the capital city.

Around the same time, the mural artists working for the Institute, many of whom were visual artists with experience in galleries or as graphic designers in private companies, began to develop a new aesthetic for the political messaging they were tasked with conveying. In effect, they attempted a creative synthesis of the nonpolitical style of Ghadyanloo with the pure propaganda of the Imam and martyrs imagery.

Advertisement

Anti-American themes, often crudely rendered, have long been a staple of Iranian murals. But in the mid-2010s, at the height of the nuclear talks, the Institute artists started co-opting Western cultural symbolism to convey the untrustworthiness of the US as a negotiating partner.

In this example, the Iranian representative and the US envoy sit across the table from each other. On the right is the Iranian, neatly dressed, his hands on the table to show he has nothing to hide, one fist clenched in determination. In contrast, the American slouches in his chair, his body language exuding arrogance. Beneath his diplomat’s white shirt and suit jacket, he is wearing military fatigues and combat boots. Under the table, he brandishes a gun.

Another example appropriates the famous photograph of American marines raising their flag on Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima—except that here they are planting the Stars and Stripes not on a Pacific island but on a heap of destruction: broken bodies, demolished houses, and exploded cars. The iconic image of American heroism is turned on its head.

For the most part, though, this more sophisticated propaganda filled these billboards for only a few days at a time. The forces of exploding consumerism in Iranian society ensured that the space was soon taken by commercial ads. And for most of this latter period, the state itself seemed at a loss for a coherent, stable, visual theme to underpin its political mobilization. It was not until the assassination of Soleimani that it found one to replace Khomeini, who had died more than thirty years earlier, in 1989.

This first major billboard response to the Soleimani assassination was striking in its austerity of design: Soleimani’s stylized likeness against a huge, blood-red field. The phrase “your blood challenges any adversary,” inscribed in a computerized Nastaliq calligraphy, barely makes sense in English. More literally translated as “your blood calls for rivals,” it draws on cultural and linguistic understandings inaccessible to non-Farsi speakers.

Harif talabidan (to challenge, to call for rivals) refers to part of an ancient warriors’ practice, radjaz. By this custom, a rhetorical exchange would take place on battlefields of ancient Persia before two armies clashed: the mightiest warrior from each side would soliloquize, praising his own side, shouting out to his ancestors, and enumerating his reasons for confidence in victory, while at the same time hurling insults and deprecations at the enemy lines.

The verb harif talabidan almost always has a human subject, yet here the subject is khoun (blood). This billboard thus works as a succinct, modern radjaz, itself challenging on the enemies of the Islamic Republic to combat.

A different billboard featuring Soleimani (below) appeared at Vali Asr Square, one of the busiest central hubs in Tehran. Saluting the passersby, Soleimani stands at the head of a crowd designed to represent Iranians of all walks of life. The caption, which is taken from a well-known 1979 revolutionary song, translates as “Let’s move forward together, and sing in one voice: Viva, our beloved Iran!”

By Iranian standards, this billboard is notable for its diversity and inclusiveness—yet not a single cleric is represented. Save for three women in chador, no one even appears to be of a particularly religious bent. In fact, some of the women portrayed here, should they walk down the streets of Tehran wearing their scarves that way, might be stopped by the religious police.

This contradiction with official ideology reveals the intention behind the image: aware of the deep discontent in Iranian society, the authorities are using Soleimani’s popularity in an effort to repair their tattered legitimacy with their disaffected citizens—removing themselves and leaving only the general to represent the establishment.

Soleimani’s assassination has also provided the state with an opportunity to rekindle nationalist pride, a rallying point of support for Iran as a power in the region. In this image, Soleimani’s face has become a sort of map of Iranian strategic influence. The caption reads, “Soleimani is still alive,” with the hashtag #hardrevenge. Soleimani lives on as the personification of Iranian regional ambitions.

Palestine occupies a special place in this theme. The general’s martyrdom creates space for imagining a world in which the armies of the Islamic Republic vanquish the Zionist enemy and celebrate the liberation of the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

In this mural (below), Soleimani appears against the backdrop of the mosque. The simplicity of the image and its medium harken back, with an almost anachronistic quaintness, to the 1980s, when Khomeini and revolutionary martyrs appeared everywhere on city walls. Beneath Soleimani’s prayerful hands, the caption reads: “Quds [Jerusalem] is the compensation for your blood.” Yet Soleimani’s mild expression belies the martial message: he looks meeker than usual, his hair and beard whiter than they actually were. The modesty of his demeanor is perhaps a tacit acknowledgment of how distant the dream of a such a conquest in his name is in reality.

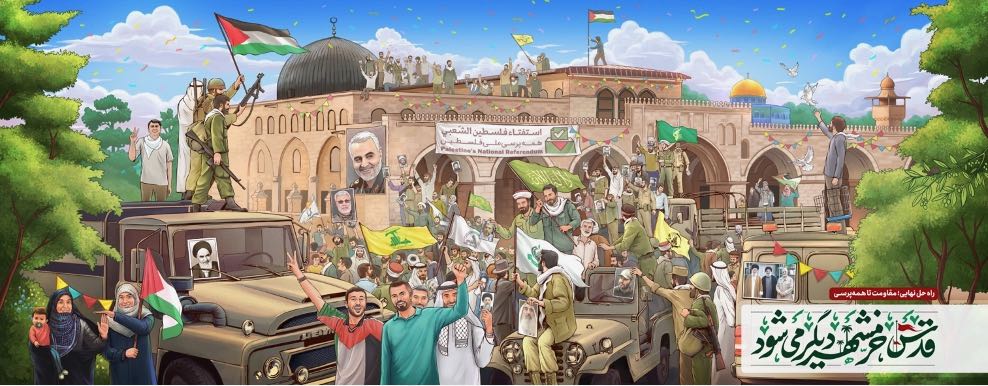

That restraint is absent from this detailed representation, below, of the utopia envisioned by the Islamic Republic. It connects a triumphant moment in post-revolutionary Iranian history, the breaking of the siege of Khorramshahr during the Iran–Iraq War, with the future capture of Jerusalem: “Quds will be the next Khorramshahr.”

The only identifiable Iranians in the image wear the IRGC uniform. Having taken over the al-Aqsa Mosque, they are celebrating with ordinary Palestinians. Iranian-backed groups like Hezbollah and Hamas are represented through symbols on and around the jeep in the foreground. The man on the hood is holding a portrait of Sheikh Yassin, the founder of Hamas, along with Hamas’s original flag. Above him, another man is waving the flag Hamas has used since 2007, when it took control of Gaza. The Hezbollah leader Imad Mughniyeh’s likeness appears several times, given pride of place thanks to his close ties with Soleimani. The yellow flag in the back of the car belongs to Liwa Fatemiyoun, an Afghan militia that also fought in Syria under Soleimani’s supervision. The ensign of Hashd al-Shaabi, an Iraqi Shia paramilitary group, also features, while the blue-and-white flag of Israel burns. The only sign of the PLO is atop the mosque in the background, where a forlorn-looking fellow timidly waves the group’s banner (the PLO is dominated by Fatah, Hamas’s rival for Palestinian leadership).

All told, this billboard represents the most elaborate treatment of the post-Soleimani utopia envisioned by the Islamic Republic, a detailed cartoon-graphic account of its idea of compensation for his blood.

This vast, nationwide campaign of commemoration for Soleimani aimed, above all, to exploit his popularity as a symbol of national unity while saber-rattling to advertise the country’s power to exact revenge on Soleimani’s assassins. In reality, both national unity and retribution have proved to be chimeras. Beset by domestic corruption and severe economic sanctions, Iran has problems that run too deep to be dispelled by poster art.

Indeed, it now looks as though the disjunction between the regime’s official messaging and its relative impotence has caused the martial, militant tone to give way to a very different mood. The following, erected at the same spot as the “Call for Rivals” billboard, exemplifies this transformation.

The occasion for this image is the newly designated National Daughter’s Day. The caption reads: “With my angels, I am close to the heavens.” Relegated now to the background, to the left of a youthful, caring father, Soleimani’s framed portrait hangs on the wall, beneficently watching over the happy family, presumably from those same heavens.

In another, similarly themed poster, two other girls are delighted at the sight of a cake. The wall behind them is decorated with a child’s painting of the Prophet Muhammad and Imam Ali. The image was created to celebrate the Shia anniversary of the Prophet’s designation of his cousin Ali as his successor, an occasion that has nothing to do with commemorating Soleimani, yet here he is again, holding the two girls in a framed photo on the shelf, as if a family member himself.

In this new phase of messaging, Soleimani is no longer at the center; a framed version of him hovers in the background, the national trauma of his loss soothed by the pious but gentle incorporation of his memory into Iranians’ daily domestic life. From the bold promises of bloody revenge to the proclamation of regional hegemony and fantasies of revolutionary justice, and finally to the quiet commemoration of the martyred general in the family home, the Islamic Republic is enacting its need to heal this wound to the nation’s pride on the walls of Tehran.