On an unusually warm Saturday morning in late May, Eyad al-Hallaq stepped out of his family’s apartment in Wadi al-Joz, a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, and walked quickly toward the Old City. It was 6 AM, and al-Hallaq, thirty-one years old and autistic, was excited to finally return to the Elwyn El Quds Special Education School, where he was training to become an assistant cook. The school runs programs for children and adults with a range of developmental disabilities and was due to reopen that morning after a long break during the first wave of Covid-19 cases. Eyad, who had cognitive ability similar to a young child’s, had been restless to get back. When I spoke to his mother, Rana, this summer, she said he had even made her take him to the school a number of times, to prove that it had actually closed.

Al-Hallaq made his way uphill to the Old City, then south along its eastern wall until he reached the Lion’s Gate, a few minutes from both Gethsemane and the Dome of the Rock. Six years ago, when he began attending Elwyn, it took a full month of training before he was able to walk that route independently. But over time, he became so committed to the program that he would arrive an hour before the staff and other students, cleaning and preparing the school’s kitchen for the day’s work.

As al-Hallaq passed through the gate, according to reconstructions of that morning, two policemen posted there observed what they thought was suspicious behavior. Eyad’s parents describe him as extremely avoidant of interactions with strangers, but this should not have been an unusual encounter for either party—the instructors at Elwyn took care to introduce their students to the guards at the gate, teaching them not to fear the heavily armed border police. They asked the guards, in turn, to be mindful that the students’ sometimes odd behavior was not a threat. Eyad, moreover, was carrying a number of IDs: an Israeli state ID, a school ID, and a card identifying him as having significant disabilities.

Nevertheless, things escalated rapidly: within seconds, a chase began, with the policemen calling on Eyad to stop and identify himself, even as they warned of a possible terrorist over the radio. Two soldiers from the Israeli Border Police (known as “Magav”) joined the pursuit, also shouting at Eyad to stop. Al-Hallaq kept running—and the more senior of the two soldiers fired twice at his legs, missing with both shots.

Eyad’s personal instructor at Elwyn, Warda Abu-Hadid, also left her home early that morning, walking through the Lion’s Gate just minutes before he arrived. According to Abu-Hadid, as she moved up the street, she suddenly heard loud shouts of “Terrorist!” followed by a number of shots. She ducked into a garbage bay just off the street to hide—and immediately after her, she says, Eyad stumbled in, falling to the floor. He crouched against one of the walls of the small space and appeared to be bleeding. Abu-Hadid says that when a number of men in uniform followed Eyad in, pointing their guns at them both, she cried, “He’s disabled!,” even as Eyad kept saying, “Ana ma’aha!” (I’m with her).

The younger of the two soldiers opened fire on al-Hallaq, striking him in the abdomen. The senior one claims to have to yelled at his colleague to hold his fire—but the shooter has testified that he did not hear this instruction. At that point, additional policemen entered the garbage bay, and, according to Abu-Hadid, repeatedly shouted, “Where is the gun?” both at her and at Eyad. Around the same time, the younger soldier fired again at al-Hallaq, from nearly point-blank range. Eyad died immediately. Barely a minute had passed since he went through the Lion’s Gate into the Old City.

*

If the murder of George Floyd, which occurred just five days earlier, is remarkable for what it sparked—a broad social movement and a powerful, sustained call for change that reignited the discussion of race and police brutality in America—then the killing of Eyad al-Hallaq is remarkable for what it didn’t. In the days that followed, the murder drew some noncommittal condolences and mild condemnations from Israeli politicians, including Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Amir Ohana, the minister of public security and a Netanyahu loyalist. In a government meeting the day after al-Hallaq’s death, Benny Gantz, the centrist politician and alternate prime minister, said, “We are really sorry for the incident,” and that “conclusions will be drawn.” A large number of Jewish Israelis came to visit the grieving al-Hallaq family in East Jerusalem, including many parents of autistic children for whom Eyad’s murder hit particularly close to home.

Advertisement

Within a week or two, though, the incident was mostly forgotten. The possible annexation of parts of the West Bank took over the headlines for a short while, only to be replaced, in turn, by a strong resurgence in Covid-19 cases. The policemen involved in the incident were investigated and taken off duty—but for the time being, at least, still walk free.

I went to visit Eyad’s parents, Rana and Khairy, in early July. The narrow street on which they live in Wadi al-Joz looks up toward the Hebrew University’s bright limestone campus on Mount Scopus, but it branches off more immediately into a main street dense with auto shops. A nearby convenience store had a photo of Eyad taped to the wall behind the counter.

Khairy greeted me with a soft handshake. He was lean, almost emaciated: his dark blue polo shirt hung loose, and the belt holding up his jeans was almost out of holes for the buckle. Grief lay heavy on the house, but both parents seemed to have become familiar with media visits, and knew how to fasten the microphones to their shirts. When I asked about the last time they saw Eyad, thirty days prior, Rana was quick to correct me: “Hamsa Wa-Thalathein,” thirty-five. Flashes of hot anger gave way to a deep sadness. Since Eyad’s death, Rana had been sleeping in his bed. Khairy, quieter, remained teary-eyed throughout our conversation.

Both parents were consumed with trying to reconstruct the events of Eyad’s final morning; they were mystified and outraged by the notion that he might have seemed a threat at any point during his interaction with the border police. Other than his IDs, Rana said, all he had on him were rubber gloves and a mask, per the Covid-19 regulations, and his phone. “I had to shave him myself every morning,” she added, dispelling the notion that he could possibly have been carrying any kind of weapon, “because he feared the slightest cut from a knife.”

Immediately following the shooting, it seems that the police themselves were driven into a ferment of confusion, initially unwilling to accept that one of their number had senselessly killed Eyad. In the hours that followed his death, they searched for a cause. They interrogated Abu-Hadid, al-Hallaq’s teacher, first at the scene of the killing and then in their headquarters in central Jerusalem, asking her what she did “with the gun Eyad passed to her” (“All he gave me was a pair of gloves,” she said). At the same time, a number of police officers burst into the al-Hallaq family’s apartment, turning over drawers and furniture in a fruitless search for evidence of wrongdoing— all before informing the parents, almost offhandedly, that their son was dead.

In the weeks since Eyad’s death, Rana and Khairy had become fixated on the cameras monitoring the Old City. There are at least seven of them positioned along the short stretch—just one hundred yards or so—from the Lion’s Gate to the garbage bay. (This stone-paved path, like everything in Jerusalem, is saturated with history and symbolism: a wall plaque notes that it is a part of “the road along which Jesus walked from the place of his trial to the place of the crucifixion,” known as the Via Dolorosa). Two cameras point inside the bay itself, showing the extent to which the Old City is surveilled. According to a municipal services worker I spoke with in the space, in which four bullet marks are still visible on one of the walls, the police came and confiscated all the security camera footage soon after the shooting.

Six weeks into its investigation, however, the Police Internal Investigations Department informed the family that while they had indeed “captured and examined all the security cameras immediately following the event,” the shooting itself was not captured on any of the footage. The cameras pointing directly into the trash room, they said, are privately owned, and had not been running at the time of the event. It is likely that, at some point, footage of the chase taken by the police’s own CCTV cameras at the gate and along the street will be released—giving the family and the public a partial picture, at least, of how the event unfolded. As to why it took six weeks to let the family know that Eyad’s actual killing had not been captured on camera, a spokeswoman for the department said the delay was intentional: investigators had wanted to keep any certainty about whether there was footage from the policemen they were questioning, so that their interview testimonies would hew more closely to the truth.

Advertisement

Rana and Khairy themselves are not satisfied with this explanation; and to many, the absence of footage of the killing will likely remain suspicious. When I spoke with investigators during the summer, they stressed they were pursuing all leads, and that the absence of video would not impede a full investigation. A number of eyewitnesses, Abu-Hadid among them, had by then given official testimonies; and in late August, the investigators conducted a formal reconstruction of the event in the Old City, tracing the chase from the Lion’s Gate to the trash room where Eyad was shot. But for Eyad’s mother, Rana, neither proof of the police’s brutality nor ensuring adequate punishment for the shooters was the main reason she cared about the footage. “I just want to see him one last time,” she said. “And then the world can go to hell.”

*

On my drive back to West Jerusalem from the Old City, I attempted to reconstruct in my mind the events of the morning al-Hallaq was killed. The way in which the incident initially transpired—the sudden, unexpected escalation and the violent chase—is not hard to imagine unfolding. There had been a number of attacks on border police by Palestinians in the months before al-Hallaq’s killing, and it is likely that the guards were more tense than usual. Just five days earlier, on May 25, there had been an attempted stabbing in East Jerusalem; and in late April, a corporal in the force had been run over and stabbed by a Palestinian at a checkpoint a few miles southeast of the Lion’s Gate. Moreover, one of the border police who gave chase to al-Hallaq was relatively new to the force, the equivalent of a college sophomore in age, and perhaps felt fear when he saw an adult Arab man behaving oddly, especially after hearing the word “terrorist” shouted over the radio. The job of policing Israel’s porous border with the West Bank sometimes demands split-second decisions in the face of what are often real threats; it is inevitable that these will sometimes be the wrong decisions.

But the brutal scene in the trash room, which begins with Eyad cowering against a wall and culminates in one of the policemen firing bullet after bullet into him, defeats any such reasoning. Rana told me that even in routine, day-to-day situations, loud noises and commotion could make Eyad curl up in a fetal position. However those final moments of his life played out, it is almost unimaginable that the police believed their lives were at risk. Comparisons between race relations in America and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict are often glib and sometimes cynical; but like the sustained, minutes-long pressure on George Floyd’s neck, Eyad’s killing reflects a level of ruthlessness that could only occur if the law enforcement officer saw the other as a potential instrument of violence rather than a fellow human being. Israel’s decades-long occupation of the West Bank (June marked its fifty-third anniversary) has left a deep imprint on both occupier and occupied.

And then there is Eyad’s autism. Even as it elicited public sympathy after the fact, his disability was almost certainly a factor in that morning’s heartbreaking outcome. Someone more attuned to the rules of interaction with the police would have recognized the power dynamic and the risks, and would have known never to run. But given the measures the school’s staff had taken to ensure the local border police were acquainted with the special needs of their charges, the burden of responsibility lies squarely and heavily on the police misconduct in this case. Eyad’s case is hardly the first time a routine encounter between Israelis and Palestinians went off the rails and ended in tragedy, but his killing reveals how tenuous any semblance of normalcy is—how quickly it can fray, become lethal, at the slightest deviation from the standard code of conduct.

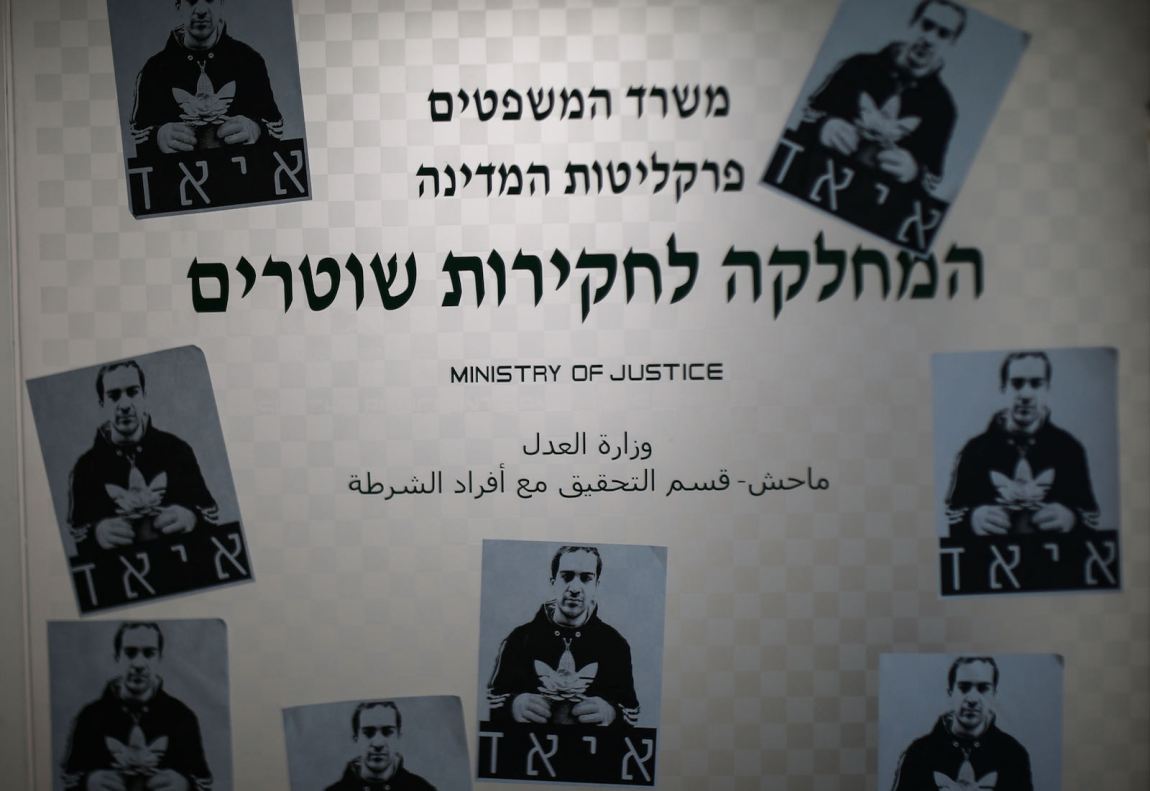

In late October, the Police Internal Investigations Department decided to charge the policeman who shot and killed al-Hallaq with reckless manslaughter, pending a further hearing. In its press statement, the department cited the “circumstances of the event,” among them al-Hallaq’s being unarmed and presenting no threat to the police or public. In this admission, the event stands out: according to the Jerusalem-based human rights organization B’Tselem, eleven Palestinians have been killed by Israeli security forces over the past two years while fleeing and posing no immediate danger, most of them shot in the back. None of the shooters, soldiers and police officers, were charged in those cases.

Saddest, perhaps, is the extent to which many Israelis will see Eyad al-Hallaq’s death as an unfortunate consequence of the fight against terrorism yet remain convinced that the current status quo in the conflict is inevitable. The possible annexation of the West Bank, source of much heated debate in June, has been postponed for much the same reason that the peace process seems to have stalled indefinitely: most Israeli Jews are fine with things the way they are. A certain “anti-solutionism” has set in, even among left-of-center citizens, who are politically animated primarily by their distaste for Netanyahu and his multiple allegations of corruption. Tragic events like al-Hallaq’s killing occasionally bring the conflict to the fore, and in a less cynical climate, the murder of a young autistic man might have brought a moment of real reckoning. But Israelis have become so practiced at reciting the events that have led to this moment—a litany of bad-faith negotiations, intifadas, and failed agreements—that they’ve become almost inured to the possibility of change.

Still, throughout the wave of protests that has unfolded in front of Netanyahu’s official residence over the past few months, among the many demonstrators calling on the prime minister to quit, a small but committed group has shown up, week after week, with signs reading “Justice for Eyad.” Perhaps change always seems impossible until it happens; perhaps a movement may yet come of this.