“What’s it like to have the entire place to yourself?” the security guard at the New Museum—an older Caribbean-American man wearing a blue uniform and black mask—asked me during my visit to Jordan Casteel’s exhibition “Within Reach” in late November. It was my first trip to a museum since last March, when the pandemic shut down New York City, and as the months passed, I had become more and more accustomed to the emptiness of previously crowded places. But as I made my way through the rooms of Casteel’s large-scale oil portraits of family members, college students, fashion designers, and subway strangers—nearly forty of them in all—I hadn’t noticed that the security guard and I were the only two people there.

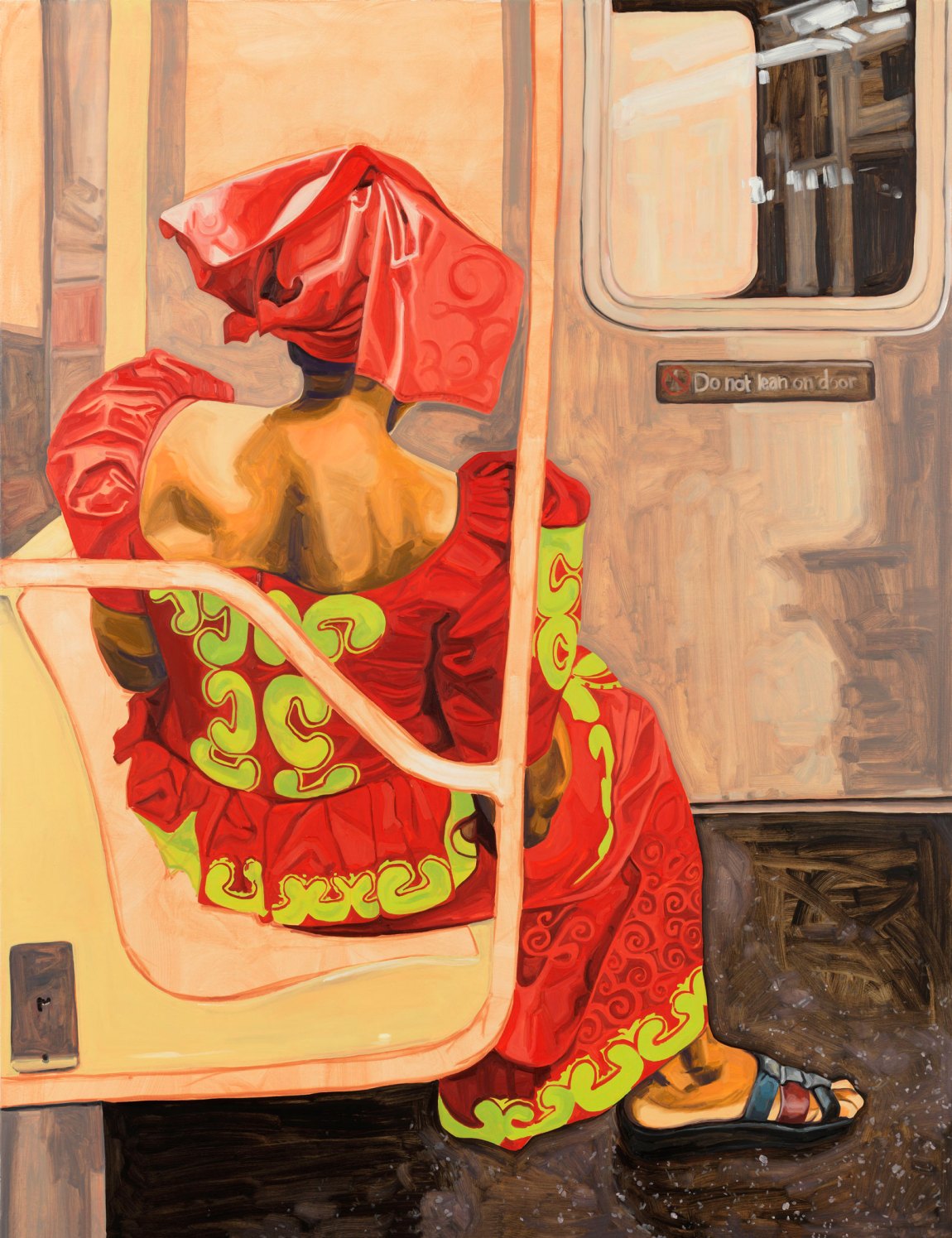

“Within Reach” is Casteel’s first solo museum show in New York City. It opened in February, just before the pandemic closures and soon after her 1,400-square-foot mural The Baayfalls—based on a painting she made in 2017 of the Senegalese-born fashion designer and Harlem street vendor Fallou Wadje and her brother, Baaye Demba Sow—went on display at the High Line. While the museum was closed, Casteel’s exhibition was available only virtually, an experience that offered viewers a rare opportunity to hear a description of her paintings in her own words. With James (2015), she says, she instantly recognized the potential for a portrait as she passed James selling CDs outside Sylvia’s Restaurant, while she was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2105–2016. “There was a light that shone on him that I’ve never seen a light shine on anyone in my life,” she recalled. But she almost missed the moment. “I was too much an introvert and too terrified to approach him,” she said. “But I realized that I made a grave mistake, that the world had literally handed me a painting on a stick.” So Jordan went back and photographed him, an exchange that “changed everything” for her.

This summer, Vogue commissioned Casteel to make a painting of a person of her choice for one of two historic covers for their September issue (the other was by Kerry James Marshall). Casteel chose to portray Aurora James, the creative director of the sustainable luxury brand Brother Vellies and the founder of the 15 Percent Pledge, a nonprofit that James created in response to the Black Lives Matter protests in June that calls on major retailers to dedicate 15 percent of their shelf space to Black-owned businesses. “I believe that what Aurora is doing is hugely important in creating the long-term change that Black people deserve and this country owes us,” Casteel told Vogue. “I see her as a light in a lot of darkness, and a potential for hope, a representative of change across all creative industries.”

Originally from Denver, Colorado, Casteel graduated with a degree in studio art from the all-women’s Agnes Scott College in Atlanta, Georgia, earned her MFA from Yale School of Art in 2014, and is currently an assistant professor of painting at Rutgers University–Newark. She credits her family, however, for her understanding of art’s relationship to social change. Her father, Charles L. Casteel, is a corporate lawyer and avid art collector, while her mother, Lauren Young Casteel, is the president of the Women’s Foundation of Colorado, and the daughter of famed civil rights leader Whitney Young Jr. Casteel and two brothers (one whom is her twin) were also raised by their grandmother Margaret Buckner Young, a lifelong educator and one of the few African Americans to serve on the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the 1980s. As a result, her childhood was enlivened by her family’s active collecting of Black art, and their lively conversations about how Black creators seek to define and defy the world.

I spoke to Casteel over Zoom from my dining room in Newark, New Jersey. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Salamishah Tillet: Hey Jordan! Where are you?

Jordan Casteel: Good morning. I’m in my studio in the Bronx, but I just flashed back to being at home in Denver. My mom has had that same Romare Bearden image [“The Conversation”] that I see behind you right now hanging in our living room my whole life. It is one of my favorites. We also had Charles White’s Mother and Child.

Given that your grandmother was on the board of the Met when she lived in New York, did you also grow up in the museum world in Denver?

It’s so wild. My grandmother loved theater, dance, and the arts, and I imagine she was the sole Black woman on those boards at that time. I didn’t know much about her life here until I moved to New York City in 2015. She moved to Denver after my mom had me and my twin brother in 1989, but my family wasn’t deeply involved in museums. My grandmother did get my father into collecting, so there was always art around. And my dad told us stories of him running around and chasing down artists in New York and calling the gallerist Jack Shainman incessantly and being like, “I’m a Black man, sell me work. I’ll take a print.” He even tracked down the Faith Ringgold print Tar Beach Woodcut (1995) that was in her children’s book Tar Beach, which I loved as a kid. The first art class that my mom enrolled me in was a pinhole camera class at the local art students league. I didn’t do painting; I was really into crafting and craft supply stores like Michaels.

Advertisement

So when did you start formally training as an artist?

In high school I took a drawing class. It was put on my schedule by accident. But the teacher saw something in me and asked me to do a mural in the gym, which the assistant principal painted over because he didn’t like it. I painted these two Black basketball players.

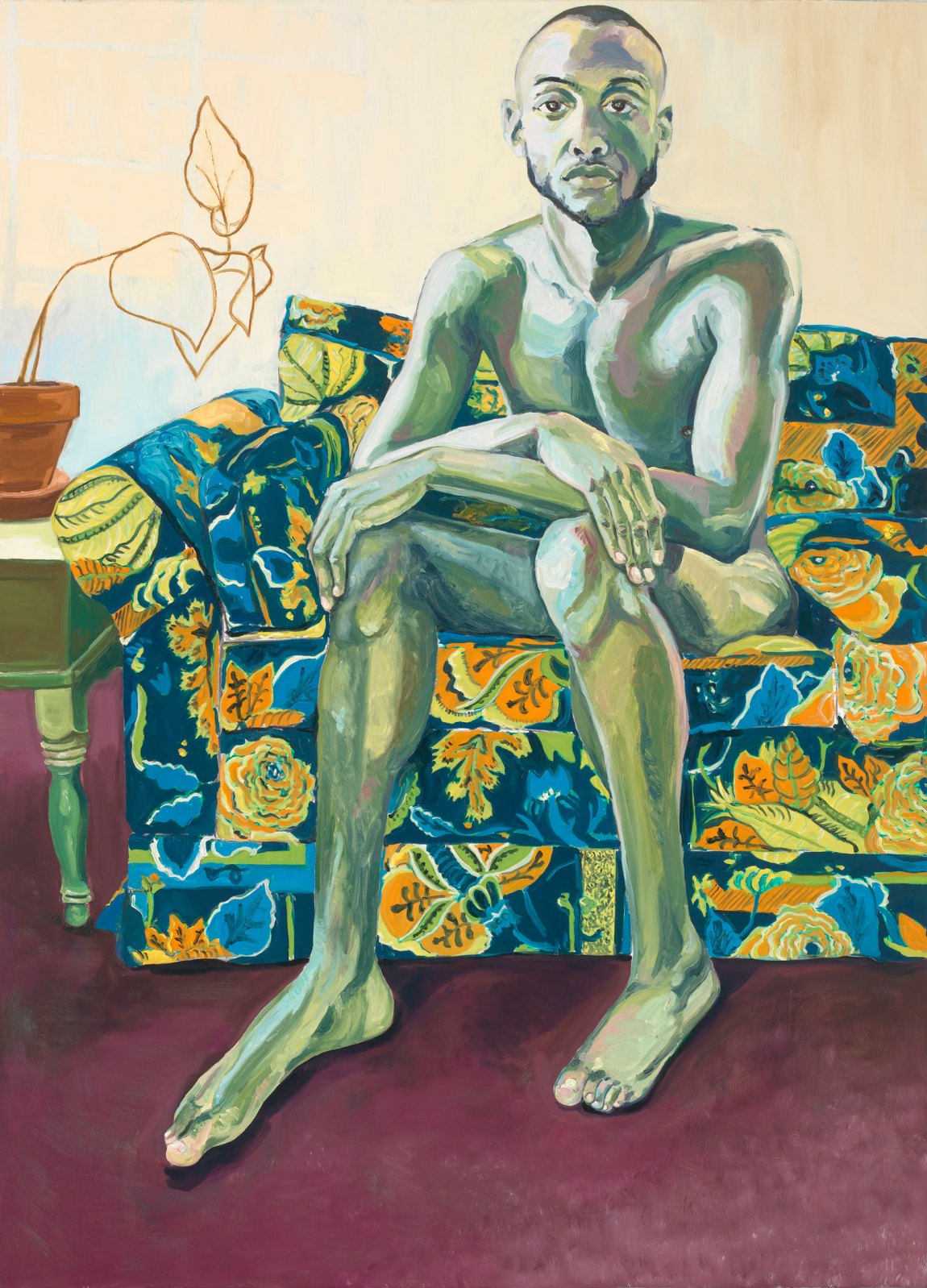

Do you think that experience informed the style and scale of your paintings? The works in your earliest series, “Visible Man,” which you did in graduate school and which are now at the New Museum, are massive.

I actually forgot about that until right now. I think that’s the kind of subconscious decision-making that was occurring for me. While I was in graduate school, I would just paint my friends. But with the nudes in “Visible Man” in particular, the scale became really important because I was thinking about the way that Black male bodies have existed in the visual and historical realms in the Americas, and how they’ve been villainized, made to feel small, disrespected. I just wanted to give them as much room as possible, and for them to be unapologetically present and wholly themselves in their humanity, regardless of their location. I also love the idea that they could feel like they’re stepping out of the canvas, and that collectors would have to make room for these people. In some cases, their feet literally press up against the frame—that of the canvas, but also it’s the frame of what they’ve been told is permissible for their existence that they’re pushing up against.

And I also love the dance that [a painting] forces you to do when it’s that big. You have to get up close, and then you have to step back, and then you get close again, and step back, and it’s a constant engagement. When you get up close, you see me. I feel myself very explicitly when I stand up close and look at the brushstrokes or the gestures. And then when I step back, I see the person in the painting, and it feels like a real relationship comes to life when you’re standing in front of the work.

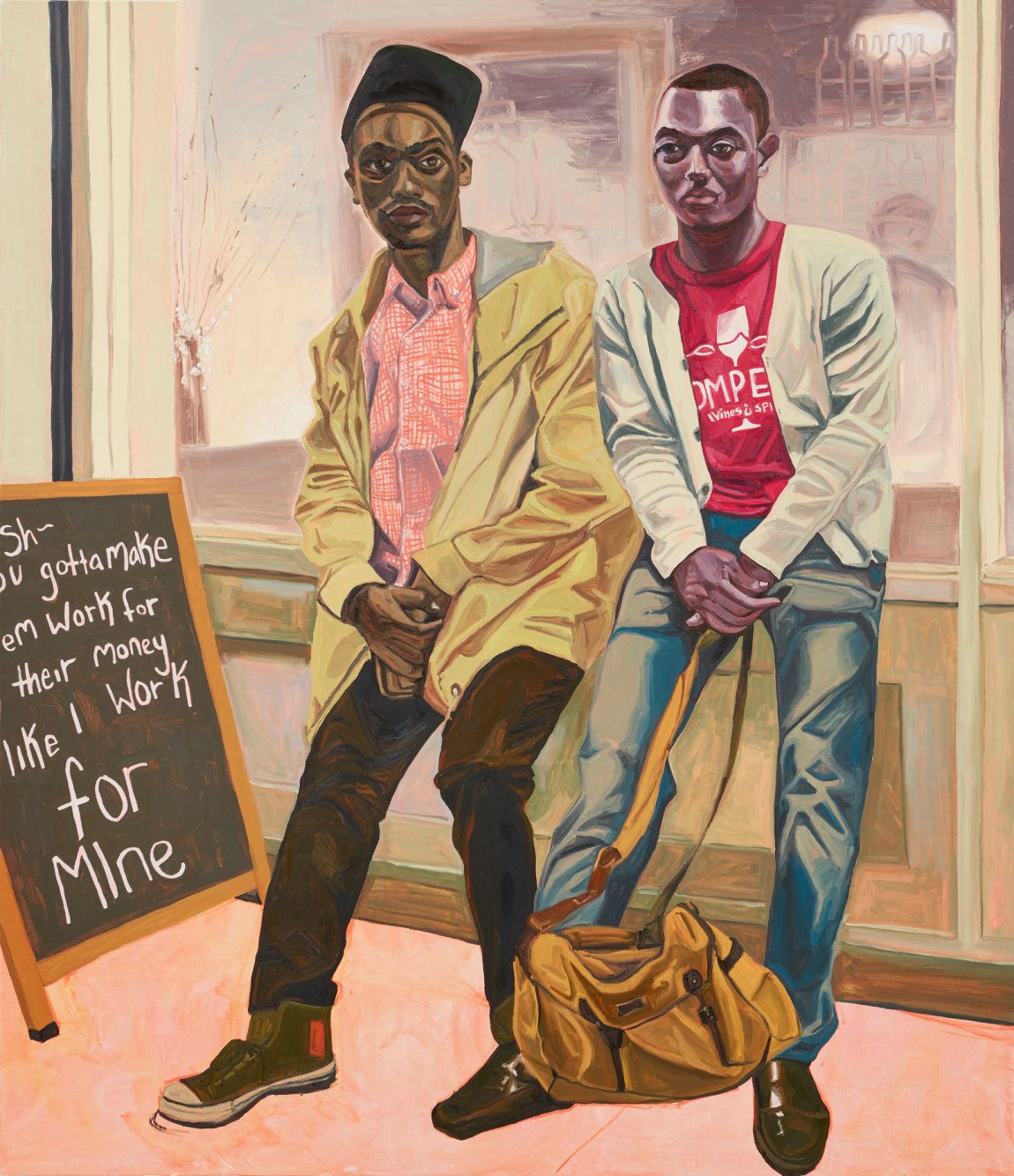

In the beginning, it seems that you were creating an intimacy between you and your Black male subjects that we viewers could experience and appreciate, but over time, I noticed your work evolved into you capturing the intimacy that Black boys and Black men have with each other.

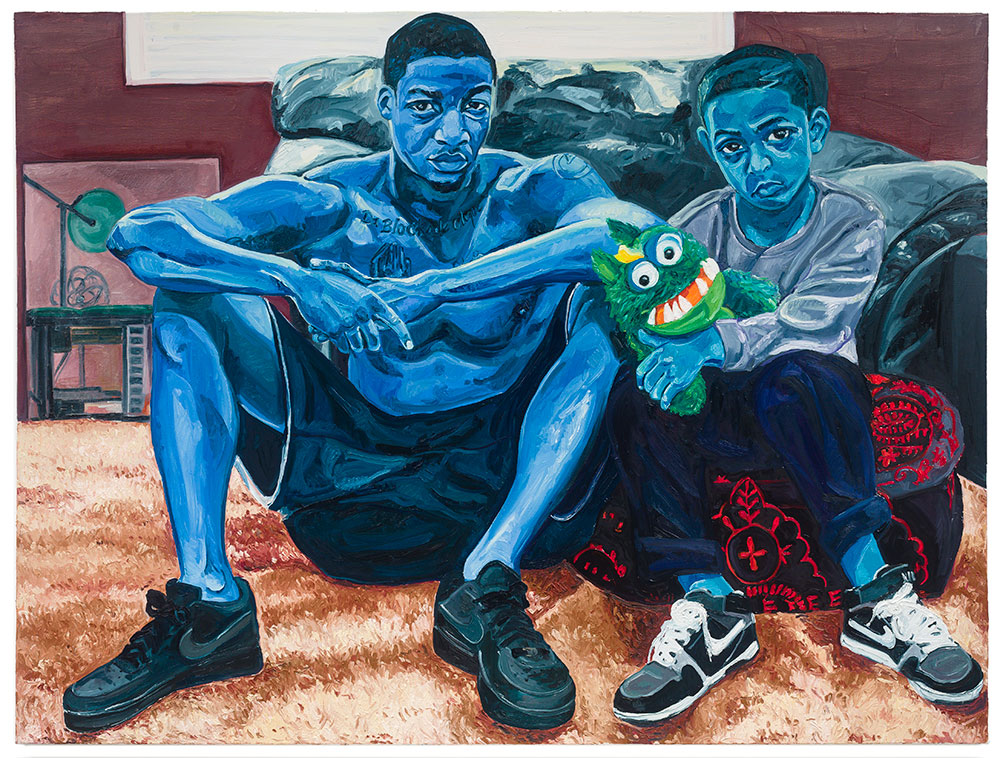

One hundred percent. I think the first painting I did in that body of work was in 2015, and it was of my brother and his son [Miles and Jojo] in which they’re blue figures. I went to my brother’s house that day with the intention of painting him by himself, and then my nephew got in the frame and was like, “I want to be a part of this.” So I kind of went with it, and then once I made that painting, I thought there was something special that occurred between them, and it created a new question for me to explore.

The blue in that painting is so dynamic.

That is probably the most intuitive part. I’m totally pulling from a random haphazard pile of colors when I’m choosing the skin tone. I was looking at a lot of Bob Thompson work and thinking about how Blackness is really expressed in a multitude of ways. Physically and emotionally the way that we all connect to our Blackness is like a mosaic. It’s not a one-two punch in the way that the world likes to imagine it. If I look at my own family, my twin brother is darker than I am, my older brother’s lighter, there’s a real spectrum that exists, I think, within Blackness and within a lot of our own families, so I was very confident in using, and very explicit in using, color to express that. And that blue was literally just a random color I picked up that my nephew says makes them look sad, but that wasn’t a conscious decision. I remember showing it to him when he was six years old, and he was like, “Why do I look sad, and why am I blue?” It was like, “Hm, I hadn’t thought that, but good question.”

Advertisement

People often link your work to the Black Lives Matter movement. Did it shape the urgency of your work?

I think it was a timing happenstance where the world was reckoning with something that I had known since I was a kid, that my life and my brother’s life could be at risk in a way that those of my white peers weren’t. I just understood something innately in my body as a young person.

At the same time, to make work as a Black woman is always going to be a political act. I think there’s no question that those themes are ever present in my work and my life as a Black woman and as a sister and as somebody who has loved many men and people of color in my life who I fear for, you know? That’s just real. But I also wanted to paint what I know most intimately, and that is my family and my friends, and a lot of those people are people of color.

Because there’s such a gap of these images in art history, I’ve been very explicit about wanting to represent them. As much as we can flood the walls of museums with Black and Brown bodies, I think, the better.