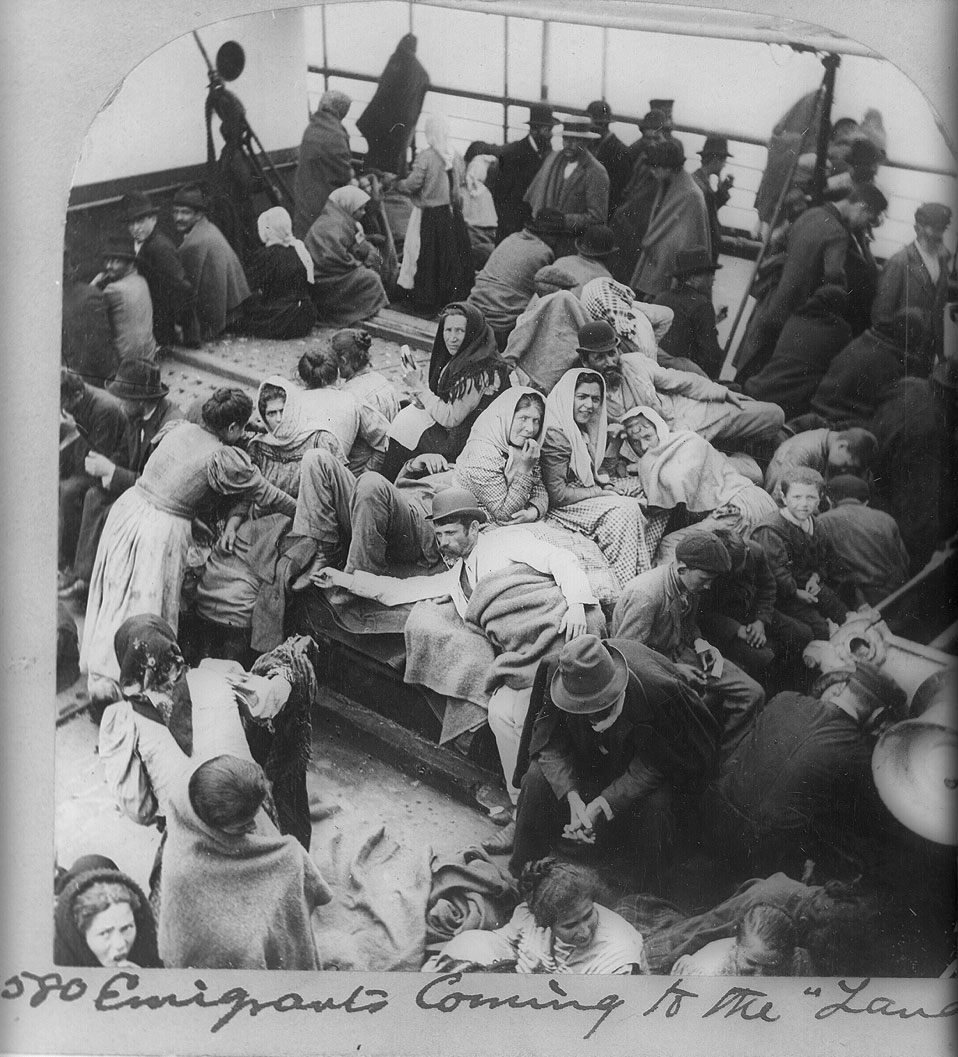

There he is, Georges Perec on site, in one of the immigration center’s old buildings, during the 1978 filming of Récits d’Ellis Island (he wrote the narration that became the book Ellis Island). We see him at a borrowed writing table, on his visit with the director Robert Bober and his crew to the island, that port of entry into “the land of the free”—at least, at first sight, to the weary eyes of the immigrants arriving on its shores, fleeing poverty, war, and persecution.

Ellis Island’s spell as an immigration center was relatively brief, lasting only thirty-two years, from 1892 to 1924, after which—until its closure in 1954—it served only as a detention center, as Perec reminds us. Yet it looms large in the collective imagination of a nation that has long prided itself on having been built by immigrants. It figures, too, in the family histories of those who were barred entry to the US and were deported back to Europe or elsewhere, which was the case for Bober’s Polish great-grandfather, who, inspected on arrival at the island, had tested positive for trachoma, a contagious bacterial eye infection that can lead to blindness and for which there was then no effective cure. Along with other infectious cases—as well as criminals, anarchists, and those deemed physically or mentally deficient (and therefore considered liable to become a public charge)—he was put on a steamship back to the Old World and never again set foot in the US.

Bober, when he learned that parts of Ellis Island had opened to the public in 1976, wanted to retrace his great-grandfather’s failed voyage and also interview Jewish subjects who had made it through the Golden Door and found a home in New York City. In Georges Perec: A Life in Words, David Bellos recounts that Bober, when inviting Perec to collaborate on the film, had to approach the writer many times. Perec was not drawn to nostalgia, or to the prospect of delving into Jewish themes. The buildings on Ellis Island, however, had sat abandoned for decades and their ruins did pique his interest.

Although annexed by Lyndon B. Johnson to the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1965, Ellis Island was not at first restored or developed. Its buildings remained vacant and prey to looters for another decade. A 1968 New York Times article described it as a “seedy ghost town,” its buildings full of what Perec and Bober later found there: “old bedframes and mattresses stacked in disuse. Tables, benches, and chairs lie about haphazardly. The floors of side rooms are strewn with broken ceiling plaster.” Except for vandals, no one visited but “pigeons and insects and sometimes Mr. Pingree Crawford,” the national park ranger assigned to oversee it.

“It was the idea of making a film about dereliction that finally swayed Perec’s mind,” Bellos writes. In June of 1978, only a few weeks after finishing his mammoth, 500-page Oulipian masterpiece Life: A User’s Manual, Perec traveled to New York City with Bober “to inspect the island and track down people who had entered America by way of Ellis Island.” Narrated by Perec, whose mellifluous cadences turn the lists of nationalities, of departure ports, and of ships’ names into entrancing litanies, the film bears witness to the Times report that the ferry that once took immigrants to Manhattan had become “a crumbling shell” floating next to a “concrete dock that is collapsing in places.” Debris had been cleared for tours led by park rangers, but the buildings wouldn’t be renovated until much later: the Registry Room; the medical examination area; and the halls where the Special Inquiry boards deliberated on the fates of those arrivals whose answers to the inspectors’ twenty-nine standard questions sowed doubts about their political affiliations or employability.

Prior to the trip, and in typical fashion, Perec worked the project he was about to begin into the novel that he was finishing. In the epilogue to Life: A User’s Manual, we learn that Cinoc, one of the elderly characters inhabiting the building on 11 rue Simon-Crubellier, “overcoming his fear of flying and of US Immigration, which he thought still happened on Ellis Island, had finally responded to the invitations he had been getting for years from two distant cousins.” You might have hesitated when reading Cinoc’s name, just as his neighbors did when he moved into the building. A list in the novel provides twenty alternative pronunciations, as well as an explanation for its gradual mutation from Kleinhof to Cinoc, all to do with the national origin of the authorities in charge of renewing his ancestors’ passports. Despite Cinoc’s ignorance of the station’s closure, it seems reasonable that the old man would be afraid of the island’s immigration officials. As lore had it, they seemed to translate last names almost homophonically, subjecting them to distortions that rendered them unrecognizable, another aspect of starting anew in the New World.

Advertisement

Perec finished writing Ellis Island upon the completion of the film in 1979, having taken on the project to reflect upon “the place where place is absent.” However, today’s Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration comes off as anything but a forsaken ruin. Rebuilt during Ronald Reagan’s presidency and open to the public since 1990, it now has a Gilded Age feel. Restored to its early 1920s appearance, there’s a sense of grandeur to the Registry Room. The building’s cafeteria boasts handsome Bentwood chairs and mahogany tables emulating the original dining room. The galleries devoted to the successful immigrants suggest that the process of receiving them entailed a restoration of dignity and personhood that dispossession and exile had threatened to strip away. Displays outline the medical attention that patients with curable conditions received before being released; the care taken of unaccompanied women and children while their male guardians were located to pick them up; and the support social workers and members of immigrant aid societies brought to the new arrivals, from donuts to employment opportunities in the city and beyond.

Not all the galleries present a rosy picture, of course: many are devoted to the family separations, deportations, and tests and systems implemented to keep emigrants out of the country, such as the puzzles to assess “feeblemindedness.” One poignant display features the brief Biblical passages that arrivals over sixteen years of age had to read in their native language to prove that they were literate, texts revealing either some bizarre empathy or mystifying callousness on the part of the immigration officers. Take, for instance, the examples in Swedish and Rumanian respectively:

And behold, there came a great wind from the wilderness, and smote the four corners of the house, and it fell upon the young men, and they are dead; and I only am escaped alone to tell thee. (Job, 1:19)

I water my couch with my tears. Mine eye is consumed because of grief. (Psalms, 6:6, 7)

This was, after all, the “Isle of Tears.” Récits d’Ellis Island opens with a sequence of the images and postcards in the scrapbook that Perec is going over before cutting to shots of the film crew aboard a ferry contemplating the same views—of a commanding Statue of Liberty and of the spellbinding waters at the mouth of the Hudson River. Both seem to be the only things that have not changed, but these are not the same waters that Perec was regarding in the scrapbook seconds earlier at his desk. And they are certainly not the same waters as today: in the more than forty years since the film, gaps in continuity are instantly noticeable, especially the Twin Towers in the background, those emblems of a geopolitical order that was radically altered by their collapse on September 11, 2001.

At the time the documentary was made, it was still possible to equate immigration with legal immigration. The civil rights movement had warmed the public to the influx of immigrants and refugees, and, in 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson had abolished the 1924 national-origin quota laws that had ended the largest immigration wave in the US’s history, favoring the immigration of fair-skinned Western and Northern Europeans. After September 11, xenophobia reappeared in the guise of patriotism and measures to crack down on illegal immigration gradually led to its criminalization, paving the way for the Department of Homeland Security and the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (or ICE) agency, and the wave of for-profit detention centers built across the US since. In 2019, on average, there were 55,000 men, women, and children confined on a daily basis, often for more than a month, and sometimes even for years.

Obama had sought comprehensive immigration reform but Congress blocked it every step of the way, and though he tried to streamline the legal immigration system and minimize the time that migrants spent at detention centers, he was saddled with the sobriquet Deporter-in-Chief by immigrant rights activists. If reliance on these facilities was in the process of being phased out at the end of Obama’s second term, Trump doubled down with his “zero tolerance” approach. Although it was rescinded in the summer of 2018, Trump’s policy separated over 2,500 children from their families; reunification is still incomplete. In the fall of 2019, by ending the catch-and-release policy, Trump sent ever more taxpayer dollars to the pockets of the private corporations running the detention centers: the largest being Core Civic and the GEO Group.

No “big, beautiful wall” protected the world from coronavirus, and the wreckage it has left in its wake will be here for the foreseeable future. Coronavirus might be novel, but the blatancy of the anti-immigrant rhetoric defining the Trump era was not. Some of the cartoons in the Ellis Island museum date back to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and others depict impossible-to-climb walls and overflowing “melting pots” of “unassimilated aliens.” “That immigration problem again!” reads the caption of a 1921 Newark News cartoon with a woman carrying a trash can that says “undesirables for America.” She stands on a riverbank; on the other side, Uncle Sam, with a club labeled “US public sentiment,” drives a sign into the ground—“No dumping ground for refuse.” Immigration advocates’ views are represented in these galleries, too. A 1916 cartoon from Puck shows a Native American chief telling a pair of pilgrims: “You can’t come in. The quota from 1620 is full.”

Advertisement

For Perec, Ellis Island was “a factory for transforming emigrants into immigrants.” Does the now commonly used term migrant point to their being in limbo, neither here nor in their places of origin, ensnared in endless bureaucratic processes and political pandering? Are they today’s occupants of that nonplace Perec found in Ellis Island? The place where place is absent, no matter how confined?

Perec understood the absurd logic of boundaries. As he wrote in Species of Spaces of walls: “There are pictures because there are walls. We have to be able to forget there are walls, and have found no better way to do that than pictures.” Or as he noted of doors: “We protect ourselves, we barricade ourselves in.” And yet, as he added on borders: “Countries are separated from one another by borders. To cross a border is quite a moving thing to do: an imaginary limit.”

Ellis Island doesn’t tell the island’s secret history as an internment camp for immigrants, prisoners of war, and US citizens of German, Italian, and Japanese descent during and in the aftermath of World War II, but it allows us to imagine how Perec would go about cataloguing it. An inventory of what is to be found in today’s American detention centers might serve as a discontinuous sequel, perhaps trumping Perec’s own summation of Ellis Island as “the ultimate place of exile.”