In 2012, archaeologists working with the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power made an unsettling find at the edge of an alkali flat known as Owens Lake, at the southern end of the Owens Valley in eastern California. Buried under the salts was an assortment of musket balls, bullets, buttons from US Cavalry uniforms, and artifacts from the native Paiute peoples (also known by their self-designation, Numa). In excavating the site, the archaeologists had uncovered the first physical evidence of a notorious massacre that had occurred over a century earlier, but that had been preserved only in oral testimonies and omitted in official US Army reports.

On the late afternoon of March 19, 1863, troops from the 2nd Regiment California Volunteer Cavalry and local militias fought a running gun battle with a band of thirty to forty Paiute fighters along a rocky escarpment called the Alabama Hills. Outnumbered, the Paiutes fled to the shores of Owens Lake and, pinned against the shoreline by the advancing whites, waded into its waters. Under the light of the moon, the soldiers and settlers lined the western shore and picked off the Paiutes. Those who didn’t die from the bullets drowned.

“The Paiutes had made their last stand at the border of the Bitter Lake,” the nature writer and novelist Mary Austin wrote forty years later, in 1903, “battle-driven they died in its waters, and the land filled with cattle-men and adventurers for gold.”

It was one of the pivotal skirmishes in the so-called Owens Valley Indian War, which started in 1860 when waves of cattle ranchers, drawn by a mining boom, came into the basin, and wrested the land from the Paiutes. For the Paiutes, the ranchers and their herds, far more than the prospectors, presented a fatal threat to their agrarian society, which included complex networks of irrigation ditches from nearby creeks to carefully tended plots of seeds and tubers. The war that ensued was a three-year cycle of cattle theft, settler vigilantism, and punitive expeditions by cavalry forces. It ended in devastating defeat for the Paiutes and their Shoshone allies. Bereft of their land and livelihood, the natives were relegated to wage labor at the bottom of the frontier order and eventually moved to reservations that exist to this day.

In the decades that followed, the waters of the lake where the Paiutes had perished dried up, the result of a transfer of mountain snowmelt and valley groundwater to the expanding city of Los Angeles. That controversial and transformative project, led by a gruff Irish-born engineer named William Mulholland, began with the city’s purchase of vast tracts of land and extensive water rights in the region, often under deceptive pretexts. It culminated in 1913 with the completion of an aqueduct to Los Angeles and the diversion of the valley’s agricultural lifeblood, the Owens River. Deprived of irrigable land and pasture, some farmers, ranchers, and townspeople later turned to violence, dynamiting the aqueduct and committing other acts of sabotage.

Today, a quarter of the Owens Valley floor is owned by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power—an arrangement that, for decades, assisted local ranchers through the city’s irrigation of leased grazing land, and that, more recently, has helped to keep unsightly urban sprawl at bay, to the delight of outdoor enthusiasts. But the valley’s indigenous activists, environmentalists, and some officials of its struggling towns have long opposed this ownership. Over the years, they have mounted, with only partial success, repeated legal actions against the City of Los Angeles to restore the water levels in the Owens River, limit groundwater pumping, and to return some land and water rights to locals. And they have good reason: with worsening climate change and the city’s recent cuts to irrigation on its leases, many in the valley could face an even drier future.

As struggles over resource extraction, the Owens Valley “Water Wars” carry echoes of the Paiutes’ resistance in the century before. And the 2012 excavation of the Owens Lake battle site represented, in a sense, a convergence of the two, chronologically disparate conflicts. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power had dispatched the archaeologists to survey the area as part of a project to mitigate toxic dust kicked up by winds from the dried-out lakebed. Before the project was undertaken, these carcinogenic plumes—caused by the city’s diversion of water to the aqueduct—filled the Owens Valley air with the largest single concentration of particle pollutants in the United States. Last fall, the valley reclaimed the undisputed title of having the most polluted air in America when the town of Bishop, at the northern end of the basin, set a one-day record during the California wildfires.

Advertisement

During the months of those fires, I caught a rare break in the smoke and backpacked through the Owens Valley’s western mountains and lingered in its towns. It was, in some sense, a homecoming to a place where my family’s roots stretched back generations, and where I’d spent childhood summers and holidays. With America coming to grips with its legacy of dispossession, amid a deadly pandemic laden with its own inequities, it seemed the right time to explore the valley’s history of appropriation and preservation.

*

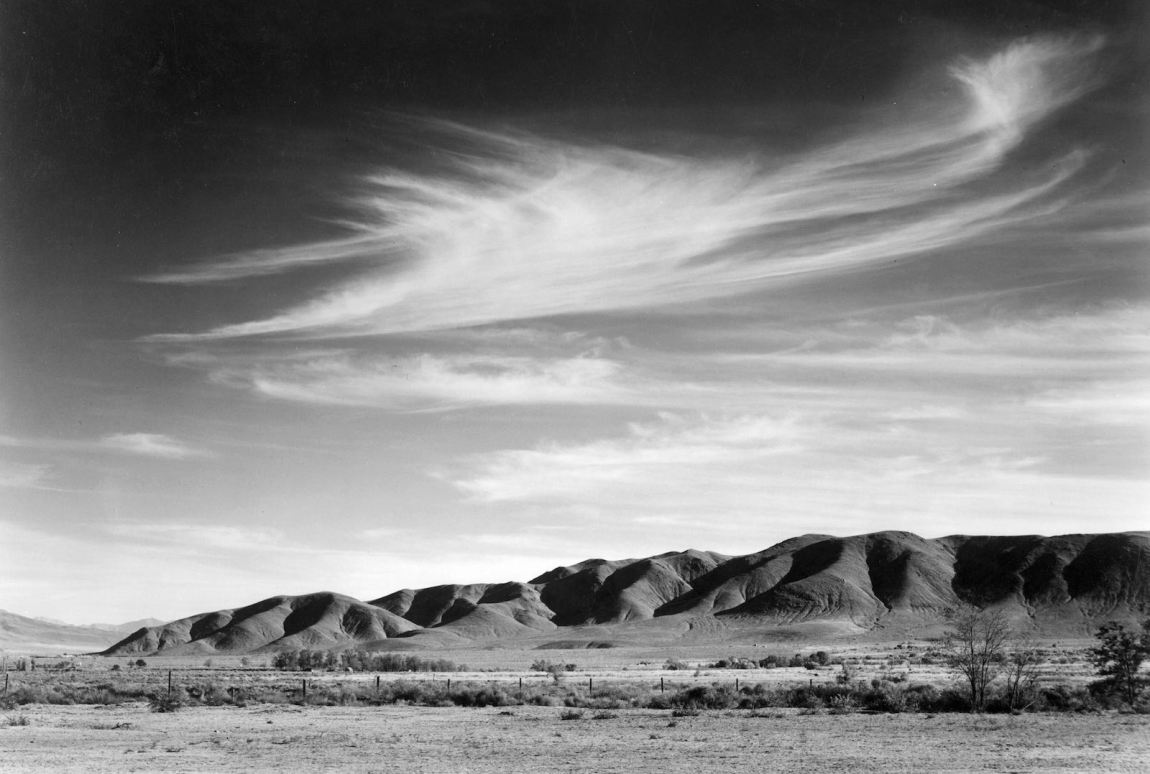

An arid stretch of land about four hours’ drive from Los Angeles, the Owens Valley is bounded by two parallel fault lines: the snow-capped Sierra Nevada mountains to the west and the White and Inyo Mountains to the east. Among urbanites, the valley is largely known as a scenic route to nearby northern ski slopes and wilderness backpacking, fishing, and rock climbing. Since the 1920s, the region has drawn countless film crews from Hollywood, who have used the rocky terrain as scenery for movies like Gunga Din, Iron Man, and Django Unchained.

The valley is also home to a shameful chapter in US history when Japanese Americans, most of them citizens, were rounded up and interned in camps by the wartime administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. One of those detention facilities, Manzanar, was constructed on the site of an old Paiute village in the shadow of the Sierras. The camp today is a place of memory, empty and stripped bare, save for a few reconstructed barracks and a guard tower, a museum, and the now-dry koi ponds once tended by the detainees.

Geologists have given a clunky technical term—“graben,” from the German for “ditch”—to the action of tectonic movement in the Owens Valley’s ancient formation. But I prefer a description from the writer Mary Austin, because it hints at the effect of human agency in modern times, as well as the region’s perplexing allure. “A land of lost rivers,” she wrote, in 1903, “with little in it to love; yet a land that once visited must be come back to inevitably.”

Those lost rivers are, of course, the Paiute irrigation canals. But they are also the valley’s major watercourse, the Owens River, diverted by the Los Angeles Aqueduct—a project that Austin opposed in its initial phase. With her prescient embrace of environmentalism, along with her defense of indigenous peoples’ rights and her feminism, Mary Austin seems a fitting guide to the region’s history and its connection to our troubled present.

Born in 1868, in Illinois, to a Civil War veteran father and a church-going mother, she attended a small Presbyterian college, pursuing studies in the natural sciences. After moving to California with her family, she married a Berkeley-educated engineer, but the marriage quickly soured. In 1892, the couple moved to the Owens Valley, where Austin separated from her husband for periods, taught school, and cared for a daughter who had severe mental disabilities. Over the next decade, she took long forays into the wilderness, making detailed notes, listening to native lore, and building a body of short stories, poems, and essays that attracted attention from editors in national publications like The Atlantic Monthly.

Settling in the tiny town of Independence, she wrote her best-known work, a collection of sketches of the valley, the adjoining desert, and its inhabitants published in 1903 as The Land of Little Rain. From the critical acclaim that greeted that slim volume, her reputation soared, and she was soon moving in literary circles that included Jack London, Joseph Conrad, and Willa Cather.

For decades, I had ignored the book, even though a first edition sat on the shelves in my mother’s ancestral home in Independence, down the street from the gabled house where Mary Austin had lived and written. Finally, on a blustery afternoon thousands of miles away on the East Coast, I opened a copy I’d acquired and started to read. The landscape that leapt from those pages was at once familiar and strange—I’d hiked its gullies, canyons, and mesas innumerable times, yet here I struggled to get my bearings. Her beguiling prose is lush with otherworldly descriptions of the flora and weather: fir trees are “star-branched minarets,” yucca leaves are “tipped with panicles of fetid, greenish bloom,” and thunderstorms “shake down avalanches of splinters from sky-line pinnacles.” Animals, meanwhile, are rendered with an idiosyncratic anthropomorphism: a coyote becomes a “water-witch,” and owls are “speckled fluffs of greediness.” But the most enduring enchantment of the book is its mythopoeic sensibility, replete with references to the lotus-eaters, the Chaldeans, Thor’s cup, and “the Iliad of the pines,” that elevates the land to a transcendent plane.

Advertisement

The Land of Little Rain is also infused with sympathetic portraits of the Paiute people, including a shaman whom Austin befriends only to learn later that he has been executed, according to tradition, when his tribe is stricken by disease and three of its members die under his care. At least one observer has uncovered traces in her book of a Paiute millenarian movement, the so-called Ghost Dance, which aimed at a revival of native society and the eviction of whites. More apparent is Austin’s outrage at the sexual violence committed by whites against the indigenous peoples, foreshadowing concerns that would emerge more vociferously in her later feminism. Women, she noted, “became in turn the game of the conquerors.”

Today, Mary Austin is more and more lauded as an early environmentalist. “Man is a great blunderer…” she wrote in The Land of Little Rain. “It takes man to leave unsightly scars on the face of the earth.” Shortly after the book’s publication, she and her husband mounted a campaign against the early planning for the biggest man-made scar on her beloved “long brown land”—the Los Angeles Aqueduct. In a 1905 article she wrote for the San Francisco Chronicle, she decried what she saw as the “craft and graft” in the city’s quest for Owens Valley water, anticipating the legal challenges and violent reactions the aqueduct would provoke in the years ahead: “I promise you there will be entered against the city of Los Angeles incalculable forces,” she wrote.

For the native peoples, the valley’s water represented not just a livelihood but the very core of their identity and cosmology. The Paiutes call themselves the “water ditch coyote children.” Coyote, their demiurge, placed them next to a water ditch—the Owens River.

*

As for me, I am very much a child of the metropolis whose growth was fueled by the diversion of that river. And three of my male relatives worked to meet its unending need for energy. My father was an engineer for Southern California’s largest electricity provider, conducting research on wind turbines and electrical vehicles to reduce the city’s carbon footprint. My maternal grandfather was an engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power who lived in the Owens Valley and worked for sixteen years on its waterworks, starting first as a chainman surveyor and hydrographer and rising to become chief engineer and general manager of the entire organization. His father before him had worked on the aqueduct and was a close friend of Mulholland, its architect, serving as a pallbearer at his funeral.

A “towering,” “no-nonsense” figure, according to a Los Angeles Times obituary, my grandfather defended the aqueduct as vital for the city, deploying the classic utilitarian argument: “The greatest good for the greatest number of people.” The water brought from Owens Valley didn’t just feed the city’s faucets, sprinklers, and swimming pools, but it enabled the livelihood and prosperity of millions. He was similarly vocal in pointing out the attendant benefits of the aqueduct for the valley’s economic development, such as a city-built railroad and paved road that transported the ranchers’ goods out of the region.

His daughter, my mother, grew up in the Owens Valley and became one of its historians, publishing an oral history of its native and white inhabitants and working as a National Park Service consultant for a museum memorializing the Japanese-American internment at Manzanar. Back when Manzanar was an orchard town, well before the camp, her grandparents had owned a general store and served as the postmasters. In the 1920s, just down the highway from Manzanar, in the town of Independence, her great-uncle had built a hotel for the visiting film crews. The Winnedumah Hotel it’s called, after a granite monolith perched on the mountain ridge east of the town. This natural pillar, according to Paiute legend, is actually a Paiute warrior who froze into stone when a rival shouted a magical command, “Winnedumah!” which means, “Stay right where you are!”

I know this story by heart because it is inscribed on a bronze plaque over the stone fireplace in the hotel lobby. On countless winter nights as a child, amid the smell of the log fire and the whoosh of the freight trucks on the highway outside, I read those lines, exulting in their ancient mystery. The owner of the hotel in those days, a part-Paiute woman, used to take me into the desert to hunt for arrowheads. These relics, and the legend, seemed like whispers from a lost world, one now conquered, appropriated, and so frozen in time. Winnedumah. Stay right where you are.

Except that nothing is so immutable. The valley is shifting today, and its places and names and ownership are contested. The Alabama Hills, where the Paiutes fought their losing rearguard action before dying at Owens Lake, were named in honor of a Confederate warship, the CSS Alabama, by miners sympathetic to the secessionists. Now, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, there’s an effort afoot to remove that name. But replace it with what? Long before last summer’s awakening, the Paiutes had rejected the Confederate epithet, revering the hills as the site where, in one of their founding myths, a rampaging giant had come down from the mountains. The monster, too, met his end at Owens Lake—at the hands of a “water baby,” an aquatic, fairy-like spirit. In the twentieth century, the myth found a new resonance in the saga of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, with the giant as a stand-in for the ravenous metropolis.

High in the Sierra mountains to the west of the hills, there’s a craggy pass where I’ve often hiked, reveling in the views of the valley. This was once a Paiute trading artery before other miners, this time sympathetic to the Union, dubbed it Kearsarge Pass, after a now-vanished mining town named for a Union warship, the USS Kearsarge, that destroyed the CSS Alabama in a Civil War naval battle off the coast of France. The pass connects to a trail and wilderness area that stretches across the crest of the Sierras, named for John Muir, the famed naturalist often heralded as the father of America’s national parks. In the centuries before, the Paiute used this trail as well, calling it Nüümü Poyo or “The People’s Road.”

Muir was a contemporary of Mary Austin, and his reputation as an environmental writer has long overshadowed hers. For me, though, The Land of Little Rain outshines in every respect anything the founder of the Sierra Club wrote. The two authors were actually rivals in their day, sparring in the pages of their books over the land they both loved and its inhabitants. In contrast to Austin’s affinity for the Paiute, Muir took a disparaging view of the indigenous peoples, whom he called “dirty,” “lazy,” and “deadly.” Thanks to Black Lives Matter, his lionizers in the American conservation movement have finally been forced to confront the racism of their icon—a reckoning that for some activists has laid bare the foundational whiteness of the national park enterprise.

More significantly, perhaps, Austin objected to Muir’s attempts to impose on the landscape an Edenic pristineness fenced from any working use by humans—including the natives, whose eviction he supported. Instead, she argued for responsible, low-impact land use, especially by shepherds and indigenous people. The grazing of sheep, an animal that Muir derided as a “woolly locust,” and especially the Paiutes’ controlled burning, she noted, kept the soil healthy and guarded against forest fires. More than a century after her writings, this is a method of resource stewardship that fire scientists and policymakers are reassessing after the infernos of last year—an incipient admission that perhaps the Paiute, and Austin, were right all along.

*

One day last summer, I climbed the mountain at the southern terminus of the John Muir Trail, Mount Whitney. At over 14,000 feet, it is the tallest peak in the forty-eight contiguous states of the United States. While the twenty-two-mile route requires no mountaineering skills, it is still a formidable ascent. Almost every year, tragically, the mountain claims a toll of injuries and deaths—from falls, altitude sickness, or exhaustion, and even by the frequent lightning strikes at its summit in the late afternoon. My own hike was without hazardous incident, except that I was on the trail much longer than I’d expected, the result of dithering at the top.

Night fell as I started the last part of the descent. Soon, the mountain was cloaked in nocturnal blackness—utter, impenetrable blackness, except for the multitude of stars above—“large and near and palpitant,” as Mary Austin described them. “Wheeling to their stations in the sky, they make the poor world-fret of no account.”

Before long, the battery in my headlamp gave out, leaving me without light to negotiate the twisting switchbacks of the trail. My companion, another solo hiker whom I’d met on the ascent, saved me with a spare. She was a Mexican woman, an experienced trekker in this backcountry, who told me she was from an indigenous group on Mexico’s Pacific Coast that had once thrived from fishing. When the waters were fished out, the young people of her tribe had headed north. She herself had dashed across the Mexico–California border two decades ago, working since as a house cleaner in a wealthy ranching town south of Santa Barbara. After the pandemic shuttered that business, she’d spent her days hiking in the Sierras, sleeping in the back of her car.

About an hour or two after we crossed back down below the tree line, into groves of piñon and junipers, we spotted the flashlights and indistinct faces of an approaching party of rangers. They warned us to hurry off the mountain: reports had come in that a mountain lion was trailing some hikers, they said. The rangers were going to deal with the animal.

“And so what?” the Mexican woman said angrily, after they had gone by. “This is the lion’s home.” She was right, of course.

At the trailhead, near midnight, I said goodbye to my companion and passed another bevy of armed rangers and sheriff’s deputies who’d mobilized against the big cat. I was concerned that my family and friends in the valley below might be alarmed by my extended absence. I needn’t have worried, though: from the porch of their cabin, they’d tracked me descending the mountain.

The beam of my headlamp had been floating down through the darkness like a falling star.