On December 27, 2017, a thirty-two-year-old woman climbed atop a utility box on a busy Tehran block called the Revolution Street. People usually do not clamber on street furniture in Tehran, but this particular sight was odder still for its being a woman with a stick in her hand. Perfectly focused on her task, once she found her balance, she loosened the knot of her white headscarf and removed it—exposing her dark hair that fell to her waist. Tying the scarf to one end of the stick, she began, with slow, rhythmic movements, to wave her makeshift flag.

Traffic slowed. Passersby stopped to watch. For those few minutes, the flag-waving woman had fixed people’s attention. If she felt fear, it was not visible. At that moment, she became a nexus that connected Iran’s bygone veilless time to its current era of prohibition. She was not the first or only woman to stage a public protest against gender inequity, but this particular rebellion—removal of the mandatory headscarf—broke a taboo that had ruled for nearly forty years. It was as if, in all the previous shows of dissent, women had tip-toed around that ultimate symbol of their subjugation. This was a revolutionary act, one the regime would not tolerate even on the Revolution Street, where all past rebellions in Tehran had begun.

Vida Movahed was arrested and soon put on trial. By then, everyone had learned her name. She received a two-year prison sentence, the first nine months in solitary confinement. The first time Movahed’s image flickered on my computer screen, a wave of mingled fear and joy washed over me. Here was another generation pursuing the same dream mine had had. When I had first arrived in the US, in 1985, I thought that the longing one experienced in exile had to do with being displaced. But no longer. Now I knew it had to do with being wronged and wishing to see that wrong—which drove me from my homeland—righted. I can never forget the searing anger I felt as a teenager who had to walk the blistering streets of Tehran in August in mandatory Islamic uniform. As exiles, we must cherish what little vindication comes our way—if only by finding in the fleeting image of a veil-less woman a trace of our younger selves, stealing back our freedom.

*

On January 16, 1979, Iran’s last royal ruler, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, left the country, and just over two weeks later, his nemesis, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, returned from a fifteen-year exile, signaling the end of two and a half millennia of monarchy. The post-revolutionary period presented many pressing challenges to the Ayatollah: the imperative of establishing a new civilian government and ending martial law, while ensuring national security, and the need to reopen schools and the economy after months of nationwide strikes and shutdowns. But there was another priority for Khomeini. Two weeks after the revolution, he nullified the Family Protection Act, restoring the unilateral authority of men over their wives and children. On March 3, he barred women from serving as judges. Three days later, he announced that all women and girls over the age of nine, regardless of religious affiliation, had to abide by the Islamic dress code.

Revolutionary fever ran high in those days, and most people, regardless of their political leanings, revered the Ayatollah. Such was his standing that in a referendum that April, close to 98 percent of voters checked the “yes” box next to “Islamic Republic” as their preferred form of government. There was little sympathy for those seen as sympathizers with the former regime—as the Ayatollah’s death squads, going door to door, were soon targeting any political opponent.

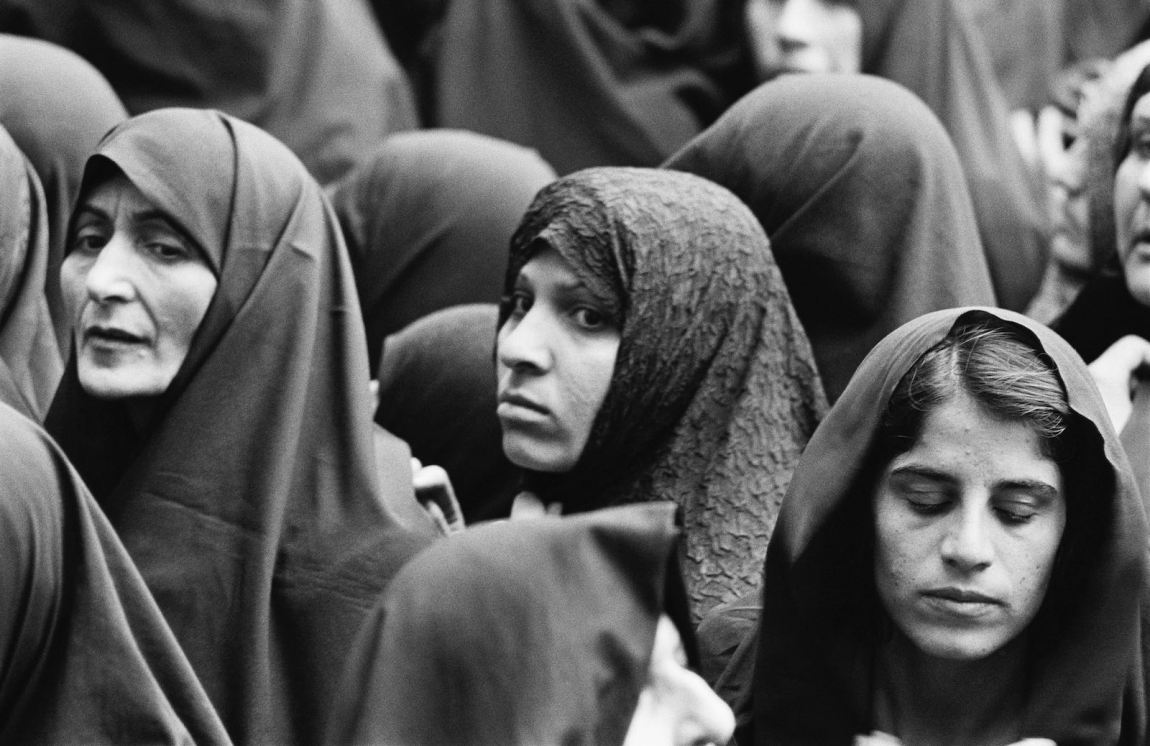

The space for dissent was shrinking, but it had not yet disappeared. On March 8, International Women’s Day, thousands of women took to the streets to protest the restitution of the mandatory hijab. “We did not rise up [against the Shah] to go backward,” they chanted. The participation of two particular groups contributed to making this demonstration historic. The first comprised women who had always worn the veil but said they did not wish to impose their choice on others and wanted women to have the right to choose how they dressed. The second involved primarily French and American feminists, some of whom, like Gloria Steinem and Betty Friedan, demonstrated in front of the Iranian embassy in Washington, D.C., while others, like Kate Millett, traveled to Tehran itself with the Committee for International Women’s Rights. They saw the Ayatollah as a threat to women’s rights worldwide and were determined to show solidarity with their Iranian sisters.

The mood of defiance was best captured by Millett, who looked straight into the cameras and called the Ayatollah “a male chauvinist.” It was the last time anyone inside the country spoke so boldly against him without suffering retribution. It also marked the end of an era in which Iranian women could call on the overt support of Western feminists in a struggle deemed universal. After that moment, such universalist claims fell out of favor among Western feminists, who came under fire in academic and activist circles for imposing their values on anticolonial movements; instead, a cultural relativism came into vogue, one that tended to view the veil as an authentic exercise of native traditions, rather than as a symbol of oppression and inequality.

Advertisement

That night, in our living-room in Tehran, I remember watching the evening news and feeling confused. The women protesting looked like women I knew, yet the official broadcaster’s anchor called them “corrupt,” even “prostitutes.” Nonetheless, the protest forced the officials to backtrack for a time, claiming that the Ayatollah had merely proposed what he thought was best for women in calling for a restoration of the veil. But this much had become clear: while the Ayatollah might rail against the Great Satan, the United States, and its ally, Israel, and puppet rulers, the Pahlavis, he was willing to act against an unnamed enemy: free and independent women. To close observers of his political rise, he was simply revealing what had always been his agenda.

*

Khomeini’s earliest objections to the Pahlavi dynasty centered on the toxic effects of Westernization, whose chief manifestation was in the unveiled presence of women in public. Reza Shah, the first Pahlavi king, had banned women’s Islamic dress code, the headscarf and the veil, in 1936. His son advanced his father’s policy with other reforms, which, among others, gave women the right to vote. In a 1963 letter, Khomeini protested to the king: “The good of the nation and the peace of all hearts rests in the close adherence of the monarchy to the mandates of Islam, which prohibits the participation of women in the political process.” In a sermon that same year, he warned of the hazards of women’s participation in the workplace: “Women will paralyze productivity in any office they enter. Whatever entity women enter, mayhem will enter along with them.”

This preaching roused social conservatives and the less educated, who were among his earliest disciples, but left secular Iranians and the educated middle class unmoved. Then, in 1964, a new law prompted a fresh intervention by Khomeini, one that changed the course of his career and the nation’s history. That year saw passage of a bill that extended diplomatic immunity to all American military personnel living and working in Iran. However, the Ayatollah, fully intent on inflaming public sentiments, unleashed a torrent of venom in which he claimed that immunity had been granted to any American in the country:

Our honor has been trampled underfoot…. The dignity of the Iranian army has been trampled underfoot!…. If someone runs over a dog belonging to an American, he will be prosecuted. Even if the Shah himself were to run over a dog belonging to an American, he would be prosecuted. But if an American cook runs over the Shah, or the clergy of Iran…no one will have the right to object. Why?

This time, the Ayatollah’s political advisers realized that his speech presented an opportunity to broaden his base, by appealing to the left-leaning elite that saw American imperialism as the root of all evil. One such adviser, a young cleric named Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani (who would later become a two-term president), recommended that the Ayatollah temper his tone about women’s rights, to maximize that appeal.

Khomeini’s capitulation speech resulted in his being sent into exile, but it also turned him into a household name. He cast himself in the image of a selfless nationalist, an Iranian Mahatma Gandhi, fighting the foreign powers who were plundering the motherland. Through the 1970s, Khomeini escalated his anti-American rhetoric, speaking of Pahlavis as “American puppets.” He even cultivated Iranian socialists by Islamizing Marxist terms like “proletariat,” “bourgeoisie,” and “classless society,” which in turn gave those concepts a wider currency. It was as if Khomeini had tried to start a fire by using patriarchy as kindling, only to realize that anti-imperialism made far better fuel.

*

After the historic March 8, 1979, demonstrations, the authorities realized that the path to repealing the right of women to choose their own attire could not be a straight one. Instead, they adopted a series of half-measures that would ultimately lead to the same goal. If they could not impose the hijab, they could order greater sex segregation—in the name of giving women the freedom to go without the hijab in female-only company. Soon, hair salons, sporting events, public pools, election sites, beaches, and private parties were all sex-segregated. Schools were also segregated, and since only women could teach in all-girl schools, and since not enough women had the training to teach advanced science and math, some all-girl schools did without those classes. As a result, girls’ education was seriously degraded, which in turn sharply reduced the number of women entering the fields of science and math in universities.

Advertisement

In championing all things Iranian, the authorities recast the hijab as just another Iranian national tradition, like the Indian sari or the Japanese kimono. And those who did not embrace the hijab risked being seen as agents of “Westoxification,” the regime term for the corruption of the authentic Iranian culture by malign Western influences. In particular, women who refused to wear the hijab were suspected of harboring closet royalist sympathies for the deposed Westernizing king. No one who wanted to stay alive, let alone keep their job, in Iran in 1980 would risk that—so people went along. In an interview, the leading woman novelist Simin Daneshvar said, “When we can rebuild this ruin of a country, restart its economy, boost its agriculture, and establish the rule of justice and liberty…then we can tend to minor matters at leisure and think over the women’s appearance and dress code.”

Even the secular left assented, arguing that debate about the hijab should not get in the way of first “completing the revolution to its successful end.” Kar, the weekly paper of the most popular Marxist-Leninist group, went so far as to promote the hijab among its female cadres, trying to retrofit the Islamic dress code to a Marxist worldview: “It is precisely to instill self-control in the individual and to increase labor productivity that Islam recommends the hijab.”

The largest Islamic revolutionary organization in Iran, the People’s Mujahedin—shortly to be outlawed by the Ayatollah and become his most formidable opposition—designed a new Islamic uniform for women. It included a black veil, the chador, that is open at the front, requiring women to hold its corners in their hand to keep it closed (unlike the burqa or the abaya, which are worn like dresses and are put on over the head). This design thus hampered women’s freedom of movement. The overall new uniform—a long, loose coat-like garment, a scarf worn down to the edge of the brows, a pair of pants, and close-toed shoes—covered all but the hands. Later dubbed the manteau, it became the standard outfit for female office workers and schoolgirls—I wore it myself all through high school. Soon, it became mandatory dress for any woman outside the home.

By 1981, with the war between Iran and Iraq already underway, the veil had transcended its status as a mere item of clothing. It was the emblem of anti-imperialism, the hallmark of national unity, an expression of cultural identity, the most effective form of resistance against foreign influence, the surest way to honor the martyrs, the safest armor to ward off toxic influences, and the greatest proof of loyalty to the Supreme Leader and the revolution.

*

When the dress code was first enforced, the Ayatollah was beginning the second year of his rule—at the head of a new, postrevolutionary government run by leaders who thought it their divine mission to reshape the world. By the end of that decade, the war was over, the Ayatollah was dead, and the regime was governed no longer by revolutionary true believers, but by pragmatists who were mostly looking out for their own interests. Iran still had no diplomatic contact with the US, since all relations had ended with the seizure of the US embassy in 1979. Then, in 1997, another blow came: the European Union cut relations with Iran, too, after the verdict of a German court implicating Iran in the assassination of four Kurdish dissidents in Berlin. To quell internal dissent and reestablish economically vital ties with Europe, the regime needed to show a new image to the world—and so, in June 1997, a smiling clergyman named Mohammad Khatami rose to power on the promise of initiating a “dialogue among civilizations,” and heralding a “reform era.”

The journalists from around the world who flocked to this new Iran reported two fundamental changes: first, the popular hatred for America had subsided; second, the “hijab police” were less visible. With diminishing enforcement, the hem of the manteau was rising, its form was becoming more fitting, its look perfectly colorful and even fashionable. This new manteau would having been unthinkable when in the 1980s, when I was a teen, when the headscarf and the manteau could only be gray, black, dark blue, or brown, and its fabric had to be thick and plain. By 1984, the year that I finally left Iran, not a week went by when I was not stopped or warned to bring my scarf forward to the edge of my eyebrows. By 1997, the scarf was barely staying on the women’s heads, and often slipped off entirely. While these were important acts of rebellion, still like all other rebellions, they needed a leader to become a movement.

*

What is most surprising about Masih Alinejad is less that a diminutive woman with an unruly head of hair could become the opposition figure most feared by the regime than that she is herself a genuine product of the postrevolutionary era and its ideology. Born in 1976, in a small village in north of Iran, she was raised in a poor, very conservative family. Her brothers were decorated veterans of the Iran–Iraq War, her father a member of the Basij, the regime’s most reliable paramilitary force. If Masih did not make her hijab perfect, it was not the police she feared. It was her father.

But her real trouble began with love. In 1996, she met a boy and married, and the young couple moved to Tehran, so that he could pursue his literary ambitions. He soon found his way into the city’s literary circles, but his wife, with her provincial accent and manners, was an embarrassment. Within a year, he divorced her.

Masih’s family, feeling disgraced, pleaded with her to return home. But she refused. She had decided to stay, learn to drive, find a job, and make a life. Her career in journalism began with an unpaid internship at a newspaper, Majles. By the year’s end, her byline was appearing on the front page. She’d surprised her editors, and herself, by her ability to charm her subjects into confiding in her—and here her rural accent had proved an asset, setting her apart from her colleagues and spurring affection from hardened politicians. Soon she was a top domestic correspondent, respected by colleagues, a favorite of readers. But she was also outspoken—which is why her editors, under pressure from the Ministry of Intelligence, barred her from covering the 2009 presidential elections. She was the most effective and beloved journalist in the country, but suddenly she was out of a job.

Disaffected, she got a visa to leave the country and traveled to England. Soon, she shed her scarf and wore a hat instead. Then, strolling down a London street one day in 2014, she took the hat off, too. The breeze blew through her hair, and she felt overjoyed. A few days later, on May 3, she uploaded a photo of her scarf-less self onto a public Facebook page, dubbing the post “My Stealthy Freedom.” In truth, she missed home and wanted to reconnect with her followers. So she invited other Iranian women to share images of their moments of stealthy freedom, expecting the page to get just a few photos. Instead, hundreds of images of women without their hijab poured in from across the country, and soon from supporters around the world.

I confess that when I first saw the My Stealthy Freedom Facebook page a few years ago, I dismissed it as another social media fad. I did not see its potential, indeed its revolutionary effect: the more women dared to participate, the more submitted their own photos. Then, three years ago, Vida Movahed, perhaps tired of acting stealthily, made her move. Following her bold public act, dozens of other women followed suit—a new campaign of protest was born, taking the Stealthy Freedom movement to a new level, with the hashtag #GirlsofRevolutionStreet.

Masih Alinejad’s social media accounts now boast more than five million followers, more than those of Iran’s president and Supreme Leader combined. She receives hundreds of video submissions weekly. Her haters send threats, but most followers are her fans. For the first time in Iran’s modern history, there is an independent voice inviting people not to follow a leader, but to lead themselves, to be the agents of the change they wish to see.

I have often wondered how Alinejad has been able to achieve what so many other feminists have not: the mass mobilization of Iranian women in revolt against Iran’s official patriarchy. The answer, in part, is that her metamorphosis from a veil-wearing woman to one who cast it off had been so public. So many women had watched her journey in its every detail that in the end, it was as if she had left an instruction manual for “auto-unveiling.” And part of the answer, too, is that it no longer made such a difference that a regime critic was isolated in exile; through social media, she was a vivid presence among her Iranian public.

A small act of civil disobedience burgeoned into widespread resistance, organized and led by women themselves. The campaign invited women to use white headscarves, signifying their peaceful act, on Wednesdays and, those who could, drape the scarf on their shoulders or around their necks. Such was the way the hashtag #WhiteWednesdays came into being. Another hashtag, #MyCameraIsMyWeapon, has given women the power to out their harassers for the world to see.

The authorities look away for the most part, hoping to avoid bringing more attention to the campaign and fueling the movement that has attracted women young and old—and men, too. There have been more arrests and convictions for women going unveiled. Six of the leading #WhiteWednesdays campaigners are currently in prison, among them Saba Kordafshari, who received a twenty-four-year sentence—ostensibly for “walking unveiled,” but really because she refused to denounce Masih Alinejad or the campaign. But few things show the authorities’ relative impotence in the face of the campaign more than the triangular caps they have had to install on top of utility boxes in an attempt to prevent more Vida Movahed–type moments.

There are still those who say the mandatory hijab is a minor issue, but the women forced to live with it see it as a daily reminder of the inequality they no longer wish to tolerate. More prominent voices within Iran, including some female members of the parliament, have come forward to acknowledge not only the reality of gender discrimination but also the way it is reinforced by the hijab as its most blatant symbol. In February 2018, the office of the President Hassan Rouhani finally released a four-year-old public opinion survey showing that at least half the country now believes that the government should not require or regulate the hijab.

In 2019, just before Covid-19 drove everyone inside their homes and put public protests on hold, the streets surrounding the former US embassy in Tehran were empty of the usual chanting crowds. At several schools and universities where US flags had customarily been laid on the ground at entrances, inviting students to step and wipe their feet on them, now the young people walked around the flags or moved them aside altogether. As for the slogans chanted at demonstrations recently, one of the most popular has been “Our enemy’s right here. They lie when they say it’s America.” Because controlling women has become both difficult and politically costly, the regime has taken a pernicious new step to transfer those costs to the citizens themselves. Since late 2020, women who are caught on traffic cameras driving without their headscarves will receive hefty fines and have their vehicles impounded, making their act of disobedience economically unaffordable. The measure also has the effect of pressing families to do the work of the hijab police by ensuring that female family members do not drive unveiled.

If the regime had been able to strike a compromise with women on the hijab when the protests first began, perhaps it would have brought the movement to a premature end. But by declaring the hijab an impassable redline, it has forced the women to recognize something they did not realize at the outset of their disobedience: they will never be rid of the hijab until they are rid of the regime.