New Age mystics believe the earth is scored by invisible lines (energy or ley lines), that otherworldly power accumulates where these lines intersect, and that such intersections are the holy places of the planet—its chakras. Saul Bellow called them axial lines. The instructor at my yoga studio calls them energy vortexes. They say it’s no coincidence that shrines and places of pilgrimage congregate in the vicinity of such intersections. The pyramids of Giza. Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives. Uluru and Kata Tjuta, domed rock formations in central Australia. Ibiza in Spain. Mount Shasta in California. And—my personal obsession—Otero County, New Mexico and the surrounding terrain: the railroad town Alamogordo, the missile range and observatory, the black military sites and secret installations, the hunting ground of the southern Apache now reduced to the 463,000-acre Mescalero reservation, and the surreal gypsum desert known as White Sands.

The area around Alamogordo was the first part of the American Southwest to be added to maps of the “new world.” It’s where Geronimo made his last stand, where black members of the Union army may have come to be called “Buffalo Soldiers,” where the first modern American missiles flew, and where flying saucers are cited and sometimes crash. It’s where the first atomic bomb was dropped. This spooky, irradiated place is the closest thing America has to a spiritual capital.

*

It’s difficult to explain the cause of my obsession, but I do know when it started. I was fifteen. I spent the summer camping with friends in the Southwest. We rafted the Snake River, hiked the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and stood at the Four Corners, an appendage in each state, as if the lines on the map really meant something. We biked along the boundary of the White Sands Missile Range, the desolate plain where Robert Oppenheimer and his team detonated the first atomic bomb, the blast that some with a peculiar cast of mind believe kicked open a portal to the next world. The spot is indicated by a stone pyramid, a marker memorializing the day: July 16, 1945. If you look carefully, you can find bits of shimmering green rock nearby, trinitite, a mineral newly alchemized in the heat of the blast.

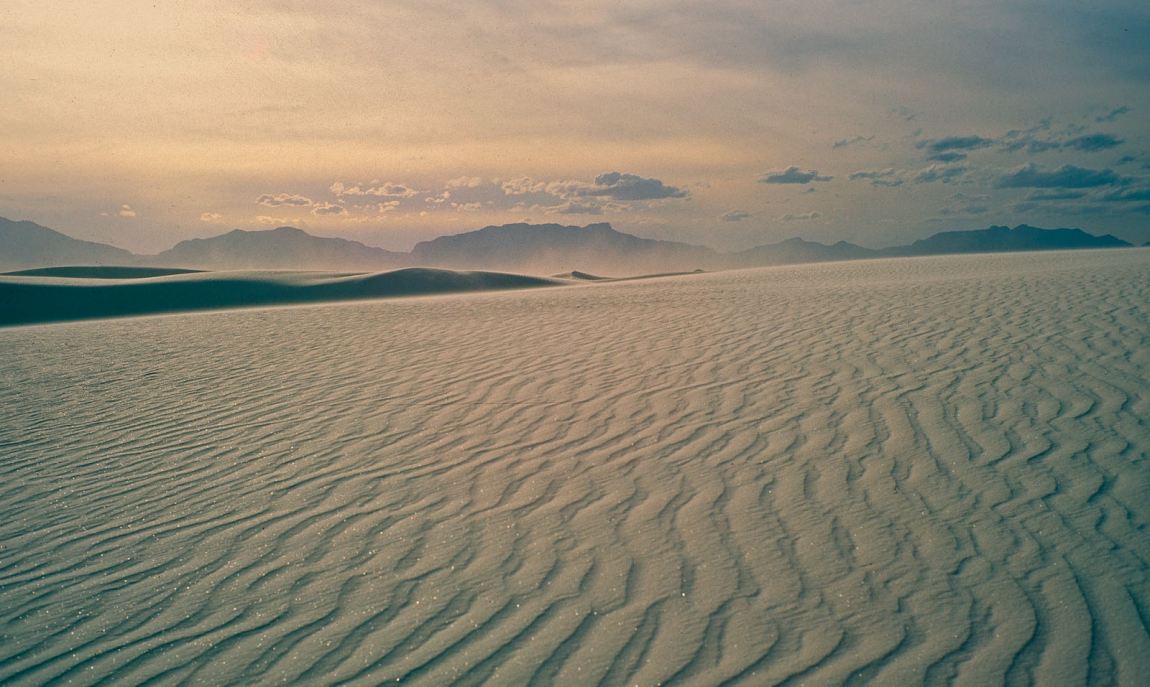

We camped in White Sands National Park, a Sahara-like sea of dunes. In the middle of the night, I stumbled out of the tent and into the universe. It felt as if I could reach up and pull down a handful of stars, as if I could see every constellation and planet and supposed-to-be-invisible chord that connected it all, the mechanism that made the whirligig turn.

The feeling I had that night—the otherworldly shiver of southern New Mexico—has been felt and expressed by writers, storytellers, and painters. It’s in the essays of D. H. Lawrence, the blueprints of Frank Lloyd Wright, the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe. It’s in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks, the most recent season of which takes the viewer inside the atomic cloud that towered above the desert and dramatizes the moment the demon was released.

I read every book and essay and treatise I could find about the region in those pre-Internet days. Histories, stories, novels. The diaries of Spanish conquistadors. The legends of Geronimo and his Apaches. I was looking for the crucial bit of information that would unravel the landscape, that would bring the White Sands into focus.

What was driving me?

I suppose I have always been hunting for God, a meaning or a pattern to life, and the place I feel I’ve come closest to finding it is in Otero County. Coronado and his search for riches, Geronimo, the atom bomb and rocket tests, the UFOs ghosting over the hills…why has this desert been the center of so much uncanny history, real or imagined? Is it the ley lines, or are the ley lines one of the fantasies invented to explain the shiver you feel when you stand alone beneath the stars? Maybe it’s the nature of the white sands, which, depending on the hour of the day and mood you bring to it, feels either brand new, still in the process of becoming, or like the oldest place in the world. If I could understand why the desert affects me so profoundly, maybe I’d know the reason for my obsession; maybe I’d know everything.

*

New Mexico appeared in the European imagination not as a new place but as the recollection of a very old place, a recovered memory.

There’s a Portuguese myth: at the time of the Moorish invasion in 711 AD, seven priests, believing the end of Christianity at hand, fled in seven ships, which took them beyond the Pillars of Hercules, where they settled seven uncharted islands, on each of which they built a city and a church. In the centuries that followed, Spanish and Portuguese sailors sometimes stumbled across one of these islands, one of these seven cities, which had grown prosperous, and they lingered there only long enough to repair their ships, pray in the church, and continue on.

Advertisement

Reported by seafarers upon their return, these islands were dutifully added to charts, but later, when captains went looking, they could not be found. The longer the mystery lingered, the more seductive the tale became. Some said houses in the seven cities were made of silver. Some said their beaches were studded with gold. The Age of Exploration, which began with Henry the Navigator in the 1400s, was partly about finding a water route to China, partly about planting sugar cane, partly about evangelizing, partly about glory, and partly about finding the seven cities.

For three hundred years, they appeared and disappeared from charts, drifting from the southern Atlantic to the Azore doldrums to the Caribbean. By the 1600s, they had turned up on maps off the east coast of North America, whence they began to move inland, forever glimmering just beyond the horizon.

*

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado did not look like the other famous conquistadors—Balboa, de Soto, de León—who fade into oil-painting antiquity. The same forked beards and stiff collars, the same dead eyes behind egg tempera. Coronado looks modern in comparison. In a characteristic likeness, he is seen in profile, features as chiseled as those of a screen star. His gaze is concentrated and happy, as if he’s about to throw four aces on the table and say, “Read ’em and weep, boys.”

In 1540, while serving as a territorial governor in New Spain, the colonial empire established in North and South America by the Habsburgs, Coronado was ordered to assemble an expedition, locate, and lay claim to the treasures of one of the seven cities, whose gleaming towers had been seen, in the fading sun, at a great distance, by a small party headed by a Catholic official named Fray Marcos.

Coronado led two thousand or so men into the wilderness north of Compostela (on the Pacific coast of modern Mexico). Among them were Native Americans in traditional robes and feathers, servants and slaves, goats and pigs to provide sustenance, and a cavalry of armored knights out of a storybook. Coronado wore a glided breastplate, leg guards, and a brass helmet with a red plume. He followed ancient trails that had been blazed and preserved by native people for thousands and perhaps hundreds of thousands of years.

Coronado’s exact path is unknown, but you can follow an approximate route on Google Earth. Leading his men from Compostela, a town on Mexico’s Pacific coast, he crossed the frontier near the present site of Agua Prieta, then headed in the Arizona desert, which is as monotonous as the background in a Road Runner cartoon.

Good trails don’t vanish; they get fortified, paved into highways. Even when its eight lanes are at a rush hour standstill, the logic of the old road can be felt beneath every switchback. If you drive on US80 from Douglas, Arizona to New Mexico, you are likely shadowing Coronado. You’ll cross a range of low brown hills into a cactus land. You’ll see tracks, but few trains; roads, but few cars; ranches, but few people. You might feel like you’ve wandered into a John Ford movie, and Cochise has led his braves off the reservation, and a West Point martinet is ordering you to do something that is both suicidal and immoral.

Coronado’s soldiers—poorly supplied and ill-equipped—were tormented by heat, hunger, thirst. By noon every day, their breastplates were too hot to touch, their swords too heavy to carry. Even if Coronado had known the truth about the first of the so-called seven cities, Cibola, he probably wouldn’t have told his men. The fantasy is what kept them alive.

The expedition was on the verge of starvation by the time it reached the city’s outskirts. The soldiers had been traveling for four months. Fray Marcos, the only member who’d previously seen the place, had seen it from a mile away, beneath a setting sun. In the fall of 1540, when he saw it again, he immediately knew it for what it was: not a gilded capital, but a poor pueblo, hovels built into a palisade. Such cliff dwellings, seen at a distance at dusk, caves lit by cooking fires, can indeed appear to be a glittering metropolis.

The “Conquest of Cibola” took less than an hour.

Advertisement

Coronado settled in a dwelling atop the village. At first despondent at the turn of events, he gradually recovered his optimism, and when the weather turned and the rains came and the prickly pear bloomed, he was overtaken by a desire to forge ahead. He sent scouts to explore the area, then report what they found. It was in this way that Europeans first came to know of the Rocky Mountains, the Colorado River, and the Grand Canyon.

Coronado’s soldiers encountered members of various tribes, including Zuni and Pawnee. One of these men, whom they captured and shackled and nicknamed, because of his headdress, the Turk, told them, through interpreters and with signs, that the legends were true, that there were indeed seven great cities in the north. He promised to lead the conquistadors to these cities—in return for his freedom.

By December 1540, the expedition had come within reach of the current site of Alamogordo. From there, they went to the White Sands.

For the Spaniards, it must have been like stepping into a fairy tale. The White Sands covers 275 square miles of the Tularosa Basin. Though a high plain, approximately four thousand feet above sea level, it had once been the bottom of an ocean. Then the continents drifted and collided, turning the depths into heights, the sea floor into savannah. When the water drained, gypsum remained, leaving behind this incredible Sahara of shifting white dunes. For Native Americans, it has always been a place of visions, disorientation, death. It’s not just the heat or lack of water. It’s the blinding glare and the evidence of an earlier dispensation.

There are old bones in the desert, the remains of defunct animal species, the giant fauna that once inhabited the Tularosa Basin: the dire wolf, saber-toothed cat, and giant sloth that were hunted to extinction by humans who crossed the land bridge from Asia.

The Turk led the Spanish deep into the unknown, continually claiming that the first of the seven cities lay just ahead.

The country was different when they reached what is now Texas. This was the Llano Estacado, the Staked Plains. To Coronado, it was a “sea of grass,” a seemingly endless expanse without tree, nor landmark. One of Coronado’s men likened it to the inside of a bowl, where the horizon rises above you on every side.

Concerned about a diminishing food supply, and the state of his men and horses, Coronado interrogated the Turk more intensely than before, forcing him to come clean: the cities of the north, the gilded buildings and treasure, the wealth, it was a lie, all of it, stories told to draw the Spanish into the crucible of the Llano, where the Turk assumed they would get lost and die and he would steal away. He had not counted on Coronado’s persistence—the strength of the fantasy, the dream—nor the fact that he, the Turk, would be kept in chains.

The Turk was put to death; Coronado pressed on. The expedition covered an unreal amount of territory. Starting at the Mexican border, they walked through Arizona, New Mexico, northern Texas, and the Oklahoma Panhandle into Kansas, continuing until they reached the site of modern Salinas, the geographical center of the continental United States, from where, standing on a hill, Coronado could see nothing but grassland ahead. According to Pioneer Tales of the Oregon Trail and of Jefferson County, the explorer left a monument before turning back, a cross with the inscription, “De Coronado reached this place in 1541.”

Coronado is a perfect patriarch for the American Southwest as his journey encapsulates the Age of Discovery in a single expedition. As with Columbus and Cortés, his evangelical and geographical mission was merely an occasion to search for every variety of wealth: slaves, fields, gold—the gold above the shrines, the gold on the fingers and around the necks of the native people, who, confused and terrorized, waved the strangers ever onward. The next island, over the next hill, that’s where you’ll find El Dorado.

*

New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin, a lowland bounded by the Sacramento Mountains in the east and the San Andres Mountains to the west, was a refuge for Apache warriors during the Indian wars. Locals can recite the names of the signature conflicts: the First Battle of Adobe Walls, where, in 1864, the Kentucky-born trader and soldier Kit Carson, backed by a few hundred cavalrymen, held off perhaps a thousand Kiowa, Comanches, and Apaches; Victorio’s War, a guerrilla conflict in which the Apache raided dozens of settlements before melting into the vastness, brutal fights in the fading light of the age. Victorio, who had black eyes and long black hair, was killed by the Mexican army in October 1880.

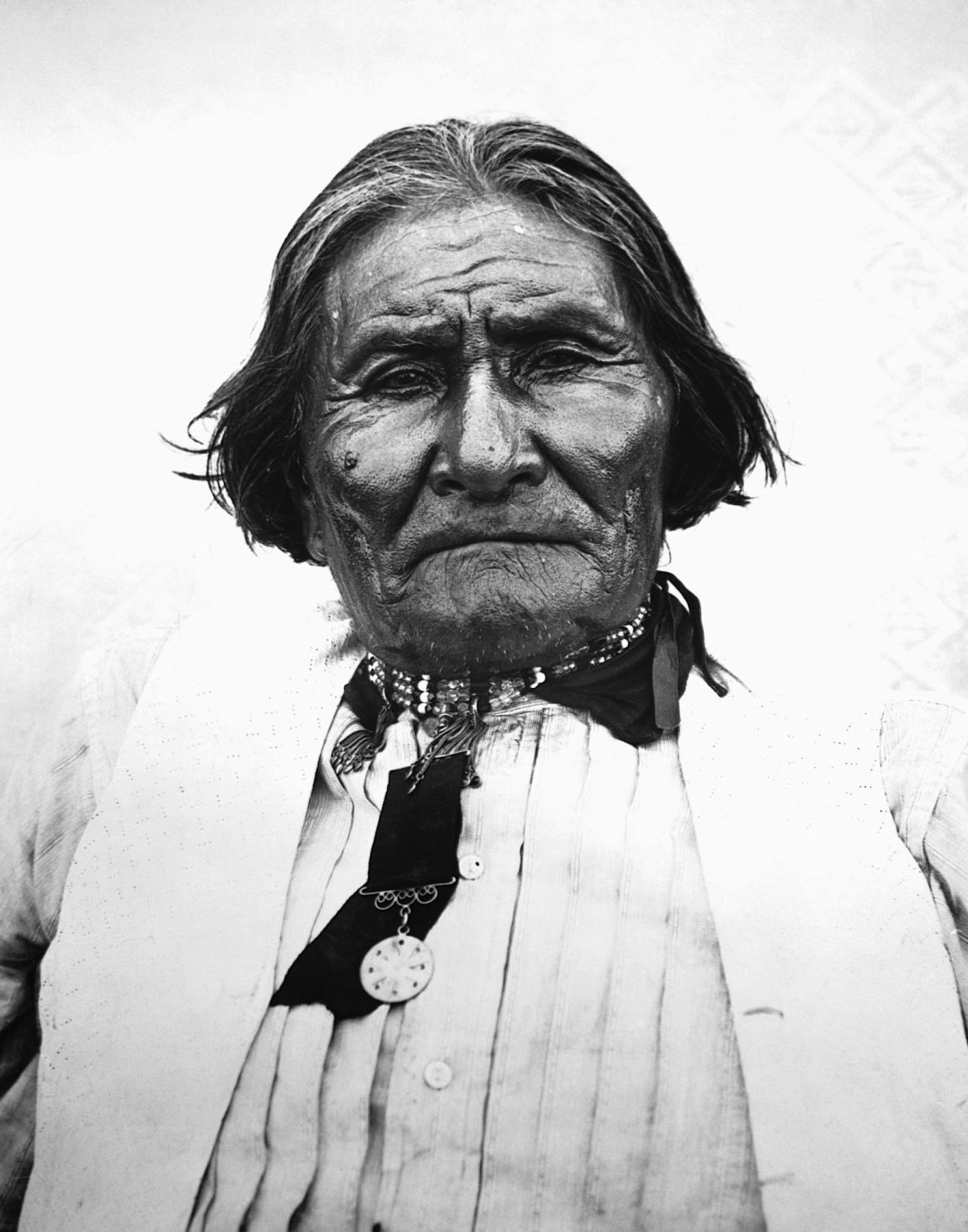

The most famous Apache of the era, Geronimo, had been forcibly settled on the San Carlos Reservation in Arizona, stayed for a time, then led hundreds of braves off the grounds and into infamy, where he remained for years, a free man at large, hit-and-running all across the region, slipping in and out of the nightmares of every rancher from Austin to Santa Fe—Geronimo the raider, Geronimo the untamed chief, Geronimo the face of death. It took five thousand American soldiers and two hundred Native American scouts to finally pin him down. He gave himself up in September 1886 in Skeleton Creek, a canyon in the Peloncillo Mountains in New Mexico. On his deathbed at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, in 1909, he said he still regretted the decision. “I should never have surrendered,” he told his nephew. “I should have fought until I was the last man alive.”

The western desert is an important place in African-American history, too. It’s where the 9th and 10th Regiments of the Union army were stationed in the 1860s and 1870s, the all-black units that were organized after the Civil War and functioned into the 1940s. The 9th, tasked with securing the road between El Paso and San Antonio, took part in dozens of battles on the frontier. Soldiers from the 9th and 10th fought Kiowa, Comanche, Cheyenne, and Arapaho in the Red River War of 1874. It was the Indians who called them “Buffalo Soldiers,” perhaps because their dark curly hair was thought to resembled a buffalo’s mane, perhaps because they fought so fiercely.

Mark Matthews, the last of the Buffalo Soldiers, died at age 111 in Washington, D.C., in 2005. Matthews, who was stationed at Fort Huachuca in Arizona in 1910, would have seen both the final Apache uprising at Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, in 1911 and the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001.

*

At a distance, he looked like a cowboy, a rider taking the view from a peak above the Sangre plains, from where he would see snowy mountains, roads, and the buildings of the Los Alamos Ranch School. Up close, he looked less cowboy than poet: a lanky, blue-eyed scientist in a porkpie hat who’d fallen in love with New Mexico during the summers of a sickly childhood. To Robert Oppenheimer, tasked with leading the Manhattan Project, the Los Alamos valley seemed like a perfect place to build an atomic bomb before the Germans did and help win the war.

Once purchased by the government, the valley was blacked out of maps. It became home to the hundreds of engineers and physicists who pledged to complete the project that had begun in 1939 when Einstein wrote FDR, warning that Nazi Germany might succeed in building an atomic bomb, unleashing a destructive force never before known in human history.

Oppenheimer recruited many of the world’s greatest scientists—Edward Teller, Richard Feynman, John von Neumann—to work in New Mexico. These men, engaged in solving practical problems—How much uranium is needed to start a chain reaction? Can a bomb be made small enough to fit in a plane? Will the chain reaction ignite the atmosphere?—can be pictured, in khaki and tweed, puffing professorial pipes, numbers dancing above their egg-shaped heads, staring across the valley at the unlettered, tobacco-chewing cowboys who once worked the same terrain: Sam Walker, who, with a handful of Texas Rangers, won the Battle of Walker’s Creek in 1844; John Coffee Hays, who pursued Comanches on the frontier; Ben McCulloch, who, if not for the measles, would’ve been killed at the Alamo, but became a hero of the Mexican War and a villain of the Civil War instead.

The Manhattan Project might have been discontinued when Germany surrendered in 1945, but Japan was still fighting, the battles in the Pacific were violent and costly, and the big technological kinks had all been worked out. Besides, how can you build a bomb like that, with all the money and prestige invested, and not use it at least once? Or maybe twice?

That’s not how Oppenheimer and his colleagues expressed the dilemma, of course. To them, there was a great danger in not using the bomb. If the war ended with mankind in possession of the bomb and the knowledge necessary to make it, yet no physical example of the existential threat it posed, they believed the chances of an atomic arms race followed by a civilization-ending war were far more likely. It had to be used, they argued, so that the public would understand why it could never be used again.

In the spring of 1944, Oppenheimer drove hundreds of miles across New Mexico in search of a suitable place to test the first bomb. He was less concerned with bystanders, the so-called downwinders, who would notice the effects of radiation only years later, than with Russian spies. In the end, he settled on a desolate expanse northwest of Alamogordo. Barracks were built, guard posts, viewing stations, and a one-hundred-foot steel tower from which, at 5:29 AM on July 16, 1945, the bomb was detonated.

Most of the observers—Oppenheimer was there, along with a few dozen other scientists, officials, and military officers—turned away at the moment of ignition. These men wore sunglasses or goggles. Edward Teller, the Hungarian physicist and future father of the hydrogen bomb, had slathered his face and arms with suntan lotion. The atomic flash that precedes the explosion is a dozen times brighter than the midday sun. Met with an open gaze, this flash can cause blindness.

The desert, which had been dark, was suddenly lit like a football field under stadium lights. The distant mountains, black a moment before, were illuminated. Every rock and ravine appeared with hallucinatory clarity. A boom followed, then a building roar. It sounded like a tornado churning across the fields. Then the mushroom cloud, which would become a trademark image for the age. There were additional explosions inside the cloud, set off by colliding molecules. The steel tower was gone, vaporized. For one thousand feet in every direction, the sand had alchemized into green glass, the trinitite named for the Holy Trinity, a reference Oppenheimer said he took from the John Donne poem “Holy Sonnet XIV: Batter My Heart, Three-Personed God.”

In the moment of triumph, Oppenheimer quoted the Bhagavad Gita: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Was this the first of the seven cities, discovered at last?

After all, what had these new explorers, these conquistadors of the atom, found but the ultimate fortune, the ultimate power?

Three bombs were built at Los Alamos. The first was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by a B-29, impossibly high, a splinter in the sun, an imperfection in the sky. Dropped from 31,000 feet, detonated at 1,900. The flash was indescribable. Birds burst into flame mid-flight. Men and woman vanished, leaving their shadows burned into sidewalks. Some 80,000 people died in the first seconds; twice as many succumbed to injuries and radiation in the weeks and years that followed. The second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki three days later.

Oppenheimer, ebullient at first, was soon overcome by terror. He later said he’d been woken from his dream by a fellow scientist, who, in a moment celebration, smiled and said, “We’re all sons of bitches now.” He became frantic to warn the world. He insisted on meeting the president. He said he wanted to tell Truman about the bomb; what he really wanted was absolution, which you can’t get from a politician, even a progressive. Truman grew impatient with Oppenheimer during the meeting, which took place in the Oval Office. Oppenheimer said, “Mr. President, I feel I have blood on my hands.” The comment infuriated Truman, who said, “The blood is on my hands.” He ended the meeting, then told his chief of staff that he never wanted to see Oppenheimer again. In a letter to Secretary of State Dean Acheson, Truman called the father of the atomic bomb a “cry-baby scientist.”

*

How long would it take a spaceship to travel from a distant galaxy—Proxima Centauri, say, where three planets, including one something like our own, orbit a red dwarf a mere 4.2 light years from earth—to New Mexico? Let’s say the crew was responding to an emergency call that came in the form of a mushroom cloud that alerted the extraterrestrial authorities to the sort of nuclear fire that can spread? If you believe the findings of Ufologists (as a field, it is known as Ufology), it would take such a craft, powered by space-warping antigravity technology, no longer to cross the universe than it takes you to walk from your bedroom to your basement.

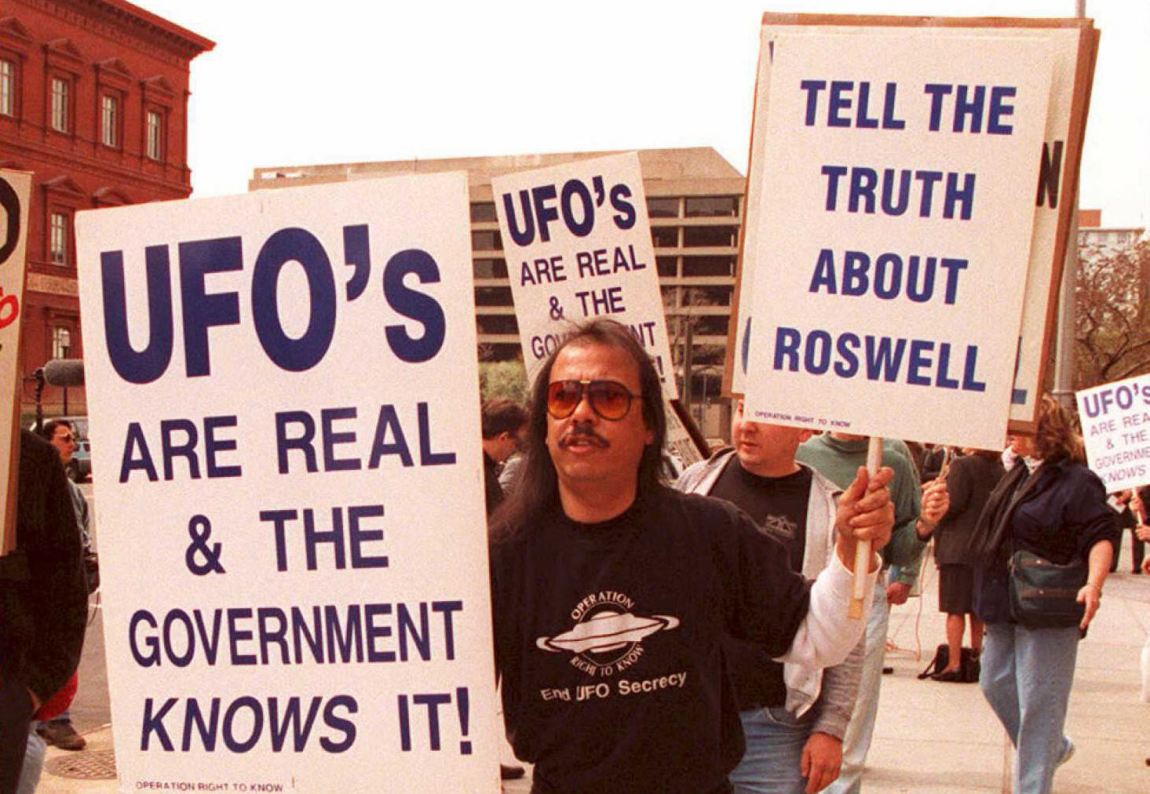

Ufologists make this circumstantial case: the first atomic bomb was dropped in White Sands in July 1945; disk-shaped craft, “flying saucers,” were reported in the skies above Southwestern deserts soon after. The phenomenon culminated on a ranch near Roswell, New Mexico, in July 1947, when a sleek ship, possibly struck by lightning, fell from the sky and skidded across a pasture. On July 8, The Roswell Daily Record ran the headline: “[Roswell Army Air Field] Captures Flying Saucer On Ranch in Roswell Region.”

The story, picked up by the wire services, appeared in newspapers across the country soon after the feds had carried away the debris, which officials dismissed as the wreckage of a weather balloon. The Defense Department rewrote the story in the 1990s, issuing a statement claiming that what crashed in New Mexico in 1947 had, in fact, been the remains of a top-secret project, a dirigible that could detect an atomic explosion anywhere on the planet.

Ufologists heard this revised statement as more obfuscation. Besides, they already knew what happened near Roswell. A UFO, sent from an alien star system to monitor mankind’s atomic experiments, went down in the desert. The bodies of alien beings—gray creatures with big heads and huge eyes—were recovered and brought for autopsy to a complex beneath Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. The banged-up saucer was taken to a secret base in Nevada, where it’s been studied ever since. Ufologists claim that as many as nine extraterrestrial ships are currently in the possession of the US government, stored in hangers at a black site in Nevada near the highly classified Air Force base known as Area 51. Some of these ships are supposedly of recent vintage, while others, having been discovered in archaeological digs, are ancient.

The Roswell incident jumpstarted a Ufology industry that continues unabated. According to the National UFO Reporting Center, an unofficial, independent body, there were 5,971 reports of UFOs in the United States and Canada in 2019 alone. Although sightings are reported everywhere, traffic has been heaviest in the vicinity of nuclear test sites and silos. According to some Ufologists, the parameters of this new age were established on February 20, 1954, when President Eisenhower met with an ambassador from a planet known only as KRLL.

UFO has, in fact, become a superannuated term. People in the know refer to the mysterious objects as UAP, Unexplained Aerial Phenomena. These days, UFOs are for kooks and late-night radio nuts. UAPs—even Ufologists speak of UAPs—are the province of serious people, secret agencies that research “close encounters”—such as a November 2004 incident in which Navy pilots, flying from an aircraft carrier near California, chased and filmed a UAP that the lead pilot, Commander David Fravor, likened in shape to a Tic Tac. Commander Fravor told reporters the craft, which had no visible means of propulsion, defied the known rules of physics, dropping from 80,000 feet to sea level just like that. Or the March 2014 incident off the Carolinas in which the pilot of a Navy Super Hornet chased a mysterious object that crossed the sky like a beam of light.

These events made the front page of The New York Times. When I asked the coauthor of the Times pieces if he believed we had been visited—that is, if he believed what he had reported others believed—he schooled me on the difference between believing and reporting.

It’s not about belief, he explained.

But I think he’s wrong. I think it is about belief—all of it: the seven cities, atomic fission, the A-Bomb and H-Bomb, the Tic Tac emerging from the heavens, the Navy commander chasing it across the sky. If you don’t believe, the crafts will not be seen or they will be explained away. If you do believe, they will turn up in every book, document, and patch of sky. Believers spot ancient spacecraft and alien creatures on the walls of Sumer, in the Torah, and in the ceremonial paintings of Native American tribes. There are three ways to regard the reports of visitation:

A: It happened.

B: It’s a lie.

C: It did not happen, but many people believe it did, which would make it not a lie but a myth. Even more than a myth, a religion, a faith for our time, the second coming in alien form, salvation from above, an otherworldly being who has descended to guide us through the inferno. Maybe the patriarchs misunderstood. Maybe the angels were aliens. Maybe the wheel Ezekiel saw burning in the sky on his way to Babylon was a supercruiser from Zeta Reticuli. When Harry Truman read the first report on the Trinity test, he asked himself if the atomic flash and mushroom cloud were what the Evangelist had in mind when he described the “fire of destruction.”

The director of the 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Steven Spielberg, returned to the topic with the 1982 blockbuster E.T. the Extraterrestrial—for devotees, the greatest book in the UFO bible, for what is this movie-myth if not the story of Jesus, a peaceful, enlightened being who has come from the beyond to suffer and die here on Earth. Here, too, are the disciples, the children who carry E.T. on their bikes, for, as Jesus says, “unless you change and become like little children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” Here, too, are the Pharisees, the government bureaucrats who want to autopsy the alien. And here, finally, is the savior’s resurrection, a triumph over death: E.T.’s ascension to the heavens in a glorious multicolored craft.

*

In 1983, E.T. surpassed Star Wars to become the top-grossing movie of all time. In its first year, the movie made nearly half a billion dollars. More than entertainment, it was a phenomenon. People stood in line to see it a second, third, fourth time. And the merchandizing, my God: all those dolls, pillows, fitted sheets, and, of course, the greatest of all tie-ins, the video game.

The movie was released at the apex of the first home-gaming boom, when millions of Americans were parked in front of their living room TVs playing Atari, a company that began with two guys in a garage and an idea that became Pong. It was revolutionary. For the first time, viewers would not sit passively before a screen, but control the action themselves. Atari was purchased by Warner Communications in 1976 for around $30 million. By 1982, it had become the company’s top division, responsible for more than 30 percent of corporate profits. Space Invaders, Asteroids, Missile Command, these games carried the company, which only increased the pressure to churn out the hits.

And what could be bigger hit-making material than E.T.? Atari paid Spielberg’s company around $20 million for the video game rights, a record sum then. The movie had been released in June; the deal was not finalized until late July—leaving Atari just a few weeks to turn the blockbuster into a game in time for the start of the Christmas shopping season.

Atari’s programmer, Howard Scott Warshaw, who had pulled off a similar feat with the Indiana Jones game, blames the absurd timetable for the disaster that followed. E.T. was a terrible game. It sold for about $20, a king’s ransom in those days. But when kids got home, tore open the packaging, and put the cartridge in the machine, what they got was garbage: a widget claiming to be the character E.T. stumbling across the screen before falling into a simulated ditch. And that was it, the whole game. Spielberg had us looking to the stars. Warshaw had us staring into a ditch. Hundreds of thousands of kids went to the mall to demand their money back; the game was a flop that helped end that first gaming boom.

For Atari, the problem was only partly financial; it was also logistical. By the following summer, the company’s warehouses were jammed with millions of unsold cartridges. What to do with this huge heap of failure? In the fall of 1983, Atari loaded its overstock in trucks and dumped it in the desert.

And where was the landfill that became the graveyard of Atari’s E.T. Jesus?

In Alamogordo, of course, capital of Otero Country, on the edge of the White Sands. And so the story of the landfill became part of the desert legend—where they’d tested the first atomic bomb, where the UFO crashed in 1947, where E.T. was buried.

Because Atari dumped their remainders in relative secrecy, some dismissed the story of the landfill altogether. As in: no way, never happened. Others believed, but didn’t care. Still others did care. And it was some of these people who, refashioned as urban archaeologists, located the lost tomb in 2014. The first cartridge was exhumed on April 26. By summer, 700,000 copies of E.T. had been unearthed in Alamogordo. And so the urban archeologists took their place alongside Coronado and Oppenheimer, seekers drawn to the place where the ley lines meet.

*

I have been back to the White Sands twice since I was fifteen: once when I was crossing the country by Toyota in search of pop culture lore; once when I was trying to make sense of the music and last days of Gram Parsons. I stood in the desert in the middle of the night on both occasions, and on both occasions, I felt the same as I did when I was fifteen—that though the universe is infinite, I could reach up and pull down a handful of stars.

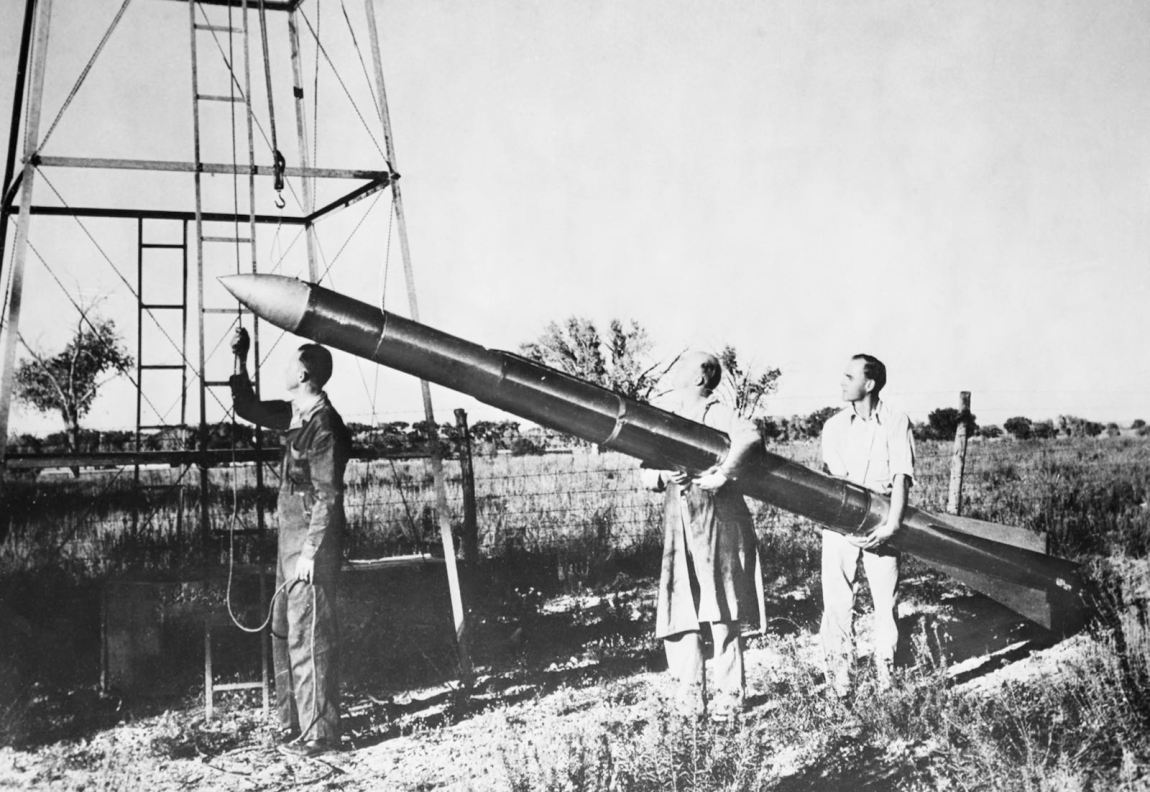

I was older each time, but nothing had changed. Every moment in the desert is the same moment in the desert. It’s as if all those numinous passages of hemispheric history—Coronado jangling by with his conquistadors, Geronimo and his braves, Oppenheimer building his tower and dropping his atomic bomb, the blinding flash and the mushroom cloud, the door torn from its hinges, the rocket engineers sending up the last of the Nazi V-2s, the ranchers spotting their flying saucers, a fleet in formation, the vision of aliens becoming a religion, and a video game that fails and is buried beneath the sand—happened not just in the same place but at the same time. As if, as per Einstein, it’s happening still.