When Merrick Garland arrived at the Justice Department on March 11 for his first day on the job as attorney general, he came with a politically unimpeachable but vaguely defined dual mandate—to renew the department’s commitment to the rule of law and to boost morale at the department. He had ably navigated his confirmation hearing, emerging with strong bipartisan support, while leaving open significant questions about how he will handle an array of unprecedented challenges, including Donald Trump’s federal criminal exposure, the misplaced priorities of the department, and an organization in a precarious state.

Garland was unambiguous on at least one subject: his disdain for the Trump administration’s so-called zero-tolerance policy along the country’s southern border, enacted from April to June 2018, which resulted in thousands of children being separated from their parents. Garland called it “shameful,” said he could not “imagine anything worse than tearing parents from their children,” and promised Congress “all the cooperation” possible to ensure accountability. This came about a month after the department’s Office of the Inspector General released a long-awaited report in mid-January (less than a week before the end of the Trump administration) that concluded that former Attorney General Jeff Sessions and senior officials at the department had “failed to effectively prepare for, or manage, the implementation” of the zero-tolerance policy.

The concerns about accountability for that policy involve difficult questions—institutional, political, legal, and moral—that will have serious long-term implications for the department. The last time the DOJ faced a similar challenge was in the wake of the torture program under President George W. Bush, and the department failed that test. It is vital that the Justice Department do better this time—for its own good, and for the country’s.

Unfortunately, the OIG’s report raises serious concerns about whether the government will be up to the task. It provides new details about how a small number of political officials developed and executed the policy, but its authoritativeness, clarity, and comprehensiveness, which some have lauded, is debatable at best—thanks to a series of subtle but crucial decisions about how the office handled the investigation. These deficiencies have gone largely unnoticed, and some of them unreported.

On its face, the report appears credulous of dubious and self-serving claims made by senior Trump DOJ officials, and it obscures important questions about the knowledge of senior officials about the objectives of the policy, as well as the involvement of career officials in executing it. In addition, according to a source familiar with the investigation, some officials within the OIG argued that senior Trump DOJ lawyers had not been truthful during the office’s investigation and that the department should have prosecuted one or more of them for lying to investigators, yet those concerns appear to have been resolved—without acknowledgment, much less explanation—in the Trump officials’ favor. (A spokesperson for the OIG declined to comment on either this or the other concerns with the report laid out here.)

The question of what can be done about any of this—what accountability looks like, and what purposes it should serve—is a complicated one. The most obvious mechanisms—through criminal, civil, and professional mechanisms, both formal and informal—face serious legal and practical obstacles. But unless the Biden administration and Congress undertake far more rigorous efforts, the country risks seeing similar abuses, and perhaps even worse ones, in the future.

*

The zero-tolerance policy, which became known as the family separation policy, was a decision to exploit the patchwork of legal rules and intricate bureaucracy that pass for our country’s immigration apparatus. It was a singularly cruel and deliberate abuse of government power that rightly provoked an outcry of public concern far beyond the broader challenges at the border that the Biden administration has inherited.

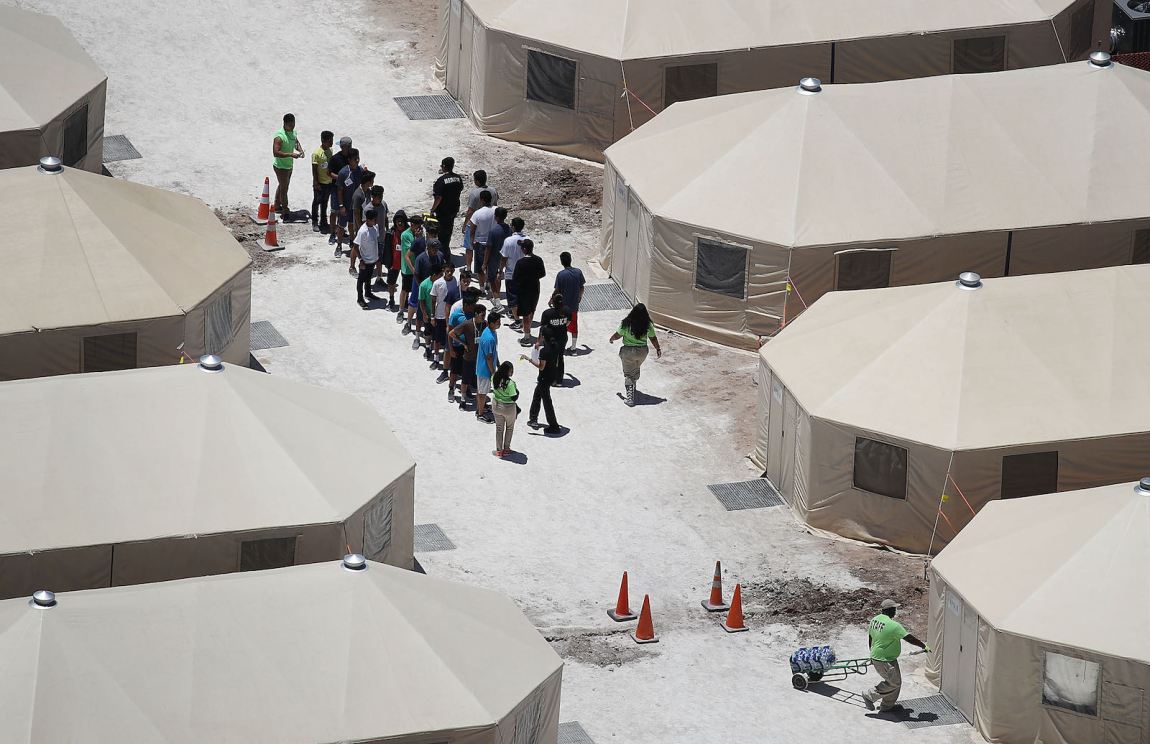

The complexities of the system are particularly acute when children are apprehended along the southern border. The law prohibits the government from holding “unaccompanied” children in criminal detention facilities and requires it to place them in the least restrictive setting possible. This generally means that the Department of Homeland Security transfers them to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement, which then places them in shelters until each can be released to an adult caretaker, pending the outcome of immigration proceedings.

In cases in which children and accompanying adults are apprehended—termed “family units” by officials—the law prohibits the government from holding children in criminal detention facilities with adult detainees or holding them in administrative detention with their parents for more than twenty days. Prior to Trump, this typically meant that the group would be released pending the outcome of immigration proceedings, assuming that the adults had no criminal history.

Kevin Dietsch-Pool/Getty Images

President Donald Trump holding a White House roundtable conference on immigration enforcement and sanctuary cities, with Attorney General Jeff Sessions, Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, and acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement Thomas Homan, Washington, D.C., March 20, 2018

Advertisement

In the simplest telling of the family separation policy, the Trump administration executed it in two steps. In early April 2018, Attorney General Sessions announced that the department was adopting a “zero-tolerance policy,” under which it would criminally prosecute everyone whom the DHS apprehended along the border and referred to the Justice Department for potential prosecution for illegal entry. At the time, this meant that apprehended family members would necessarily be separated: the government would henceforth hold the adults in criminal detention facilities, and the children—who could not be held in the same facilities and were thus deemed “unaccompanied” by the Trump administration—would be held separately by DHS and HHS.

In early May that year, the DHS formally announced that its agents would refer everyone they apprehended for illegal entry to the DOJ for prosecution. The result was to eliminate whatever remaining legal discretion that law enforcement officers along the border might have exercised when they apprehended families.

The resulting family separations prompted public outrage and protests. In late June, the Trump administration relented, and Trump issued an executive order that required the DHS to detain families together pending any criminal prosecution. (It was only recently—shortly after Biden’s inauguration—that the department rescinded the DOJ’s zero-tolerance charging policy.) Days later, in June 2018, a judge overseeing a lawsuit that had been filed by the American Civil Liberties Union declared the administration’s practice of separating families unconstitutional and ordered the government to reunite them.

A shocking amount of harm was inflicted during this relatively brief period of time. The Trump administration had not systematically tracked the children and showed little interest in addressing the humanitarian crisis caused by its actions. That task largely fell to the ACLU and its lawyers in a process of trying to trace and reunite family members that continues to this day, although the Biden administration’s family reunification task force is now, at last, expected to take over.

Lee Gelernt, one of the attorneys who filed the ACLU’s case, estimates that more than 5,500 children were separated from their families by the Trump administration, that more than 1,000 families remain sundered, and that the parents of roughly 500 separated children have yet to be located. “I never really fathomed that there would be this many children, that it would be so barbaric, that the children would be so young, that it would have been such a deliberate [effort],” Gelernt told me. “It turned out to be so much worse than we could have imagined—so, so deliberate. They [Trump officials] were so aware of the horrors that were going to occur to these children and still went through it.”

None of this could have happened without the involvement of many lawyers at the Justice Department—including not only Sessions, but also then Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein, the five US attorneys who run offices along the border, the many advisers to those people, and the career prosecutors who ultimately had to pursue the illegal entry cases in order for the policy to work. The OIG’s report attributes the resulting mess to a lack of planning and coordination: “Sessions and a small number of other DOJ officials” knew from the start that the zero-tolerance policy “would result in children being separated”—and, in fact, were “a driving force in the DHS decision to begin referring family unit adults for prosecution”—but they “did not effectively coordinate with” the US attorneys and other agencies. The report concludes that “the Department’s single-minded focus on increasing immigration prosecutions came at the expense of careful and appropriate consideration of the impact of family unit prosecutions and child separations.”

*

This sounds bad enough, as it stands. But it is not the whole story, for the OIG report’s assessment of the facts is charitable to the point of being obtuse. The crucial questions of what senior DOJ officials knew about the underlying purpose of the zero-tolerance policy and when they knew it are so oddly handled in the report as to obfuscate obvious conclusions, with the effect of making many of the central figures look much better than they likely deserve.

Sessions refused to be interviewed for the investigation, but several senior officials at the time—Rosenstein, Matthew Whitaker (then Sessions’s chief of staff), and Gene Hamilton, a counselor to Sessions who played a major part—acknowledged that they and Sessions all knew that the zero-tolerance policy would result in family separations. The report concludes that senior officials “were aware of many” of the problems that eventually resulted, but “did not attempt to address them until after the policy was issued,” and that their “stated expectations of how the family separation process would work” reflected ignorance of the governing legal requirements, “and significantly underestimated the complexities of the prosecution process.”

Advertisement

The top prosecutors along the southern border—the US attorneys for the Southern District of California, the District of Arizona, the District of New Mexico, the Western District of Texas, and the Southern District of Texas—claimed even more ignorance. John Bash, the US attorney for the Western District of Texas, presented himself to the OIG as a passive, slightly befuddled participant who did not fully appreciate the objective of the zero-tolerance policy when it was announced. He told the OIG that he “did not think that anyone expected that when the zero tolerance policy memorandum was issued, that it was a family unit policy—even though maybe we should have put two and two together.” The report says that he and the other US attorneys “expressed surprise when they learned in early May 2018 that DHS would begin referring” families for prosecution.

The implication is that there was some uncertainty about the administration’s implementing a policy that would deliberately result in family separations. In fact, there was plenty of evidence for this reported by the media from the first days of the Trump administration, including repeated statements from senior officials explaining that the objective of a policy with such consequences would be to deter illegal immigration across the southern border.

As early as March 3, 2017, Reuters published a story about a DHS proposal under which “women and children crossing together illegally into the United States could be separated by US authorities” in order “to deter mothers from migrating to the United States with their children.” CNN reported the same thing, and days later, the network’s Wolf Blitzer asked John Kelly, who was the Secretary of Homeland Security at the time, whether the DHS would “separate children from their parents if they try to enter the United States illegally.” Kelly responded, “Yes, I am considering—in order to deter more movement along this terribly dangerous network—I am considering exactly that.” Mental health professionals immediately raised concerns.

Later that month, Kelly seemed to walk back his comment and the public clamor largely died down for the rest of the year. However, the administration and the Justice Department had already begun a pilot program earlier in March in the area of El Paso, Texas that continued through November. The OIG’s report provides details from within the department during this period, but the problems—which previewed the chaos that would result when the policy went border-wide in 2018—had already spilled into public view. In November 2017, the Houston Chronicle reported on a magistrate judge in the Western District of Texas who said that he had “repeatedly been apprised of concerns voiced by defense counsel and by defendants regarding their limited and often non-existent lack of information about the well-being and whereabouts of their minor children from whom they were separated at the time of their arrest.”

The issue returned to national prominence in January 2018, after Kirstjen Nielsen had become secretary of homeland security and Kelly had moved to become Trump’s chief of staff in the White House. That month, Senator Dianne Feinstein, Democrat of California, asked Nielsen at a hearing whether the administration was “considering a proposal that would separate children from their parents at the Southwest border,” and Nielsen told her that the DHS was “looking at a variety of ways to enforce our laws to discourage parents from bringing their children here illegally,” but that “no policy decision” had “been made.” In the weeks that followed, members of Congress, as well as child welfare and immigration rights advocates, again sharply criticized the idea.

At the end of February, The New York Times published an op-ed by several advocates for immigrant children who warned that the DHS “may soon formalize the abhorrent practice of detaining the children of asylum-seekers separately from their parents” in order “to strong-arm families into accepting deportation to get their children back.” This would be a program they condemned as “tantamount to state-sponsored traumatization.” The next day, the American Academy of Pediatrics echoed those sentiments.

Sessions finally announced the zero-tolerance policy in early April, and in early May, Nielsen agreed that the DHS would detain all adults apprehended crossing the border and refer them to the Justice Department for prosecution, including those traveling with children. Sessions gave a speech that eliminated whatever ambiguity may have remained. “If you cross this border unlawfully, then we will prosecute you. It’s that simple,” he said. “If you are smuggling a child, then we will prosecute you and that child will be separated from you as required by law.”

Over the next six weeks, before Trump finally brought an end to the family separation component of the policy, administration officials—including Sessions, Kelly, and others—repeatedly gave public explanations that the policy’s express purpose was to deter illegal immigration. And as all of this was unfolding, numerous mental health professionals continually expressed horror and disgust at the separations, predicting that it would inflict serious, years-long mental health problems.

All of this information, which was available to anyone who had questions about the administration’s objectives, strongly undercuts any claim by Trump DOJ officials that they were uncertain about what the zero-tolerance policy was intended to accomplish. Yet nearly all of it is excluded from the OIG’s report. (The single exception is the Houston Chronicle’s November 2017 report, which had previously been referenced in an internal document.) The report’s failure to overlay Trump officials’ accounts of internal deliberations with the public record is more than a failure of narrative: no competent investigator interested in evaluating someone’s knowledge or mental state to establish possible culpability would categorically ignore public information widely available at the time.

*

Some of the problems with the report may have to do with the ostensibly minor but practically significant question of who actually conducted the investigation within the Office of Inspector General.

The report was prepared by the office’s Evaluations and Inspections (E&I) Division, which is typically tasked with analyzing the efficacy of programs within the department. By contrast, it is the office’s Oversight and Review (O&R) Division that customarily handles high-profile investigations that may involve serious, high-level misconduct. That is the unit that produced the OIG’s most high-profile and aggressive reports during the Trump years, including reports that criticized former FBI Director James Comey, former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe, the department’s investigation of Hillary Clinton’s e-mail, and the department’s surveillance of Carter Page.

The Justice Department’s inspector general, Michael Horowitz, did not mention any of this when he testified before the House Oversight Committee about the office’s report on family separations, but the distinction is more than bureaucratic. The aforementioned source familiar with the office’s investigation told me that the effect of delegating the investigation to one division rather than the other is “dramatic,” since, among other things, the O&R division notably employs special agents, as well as former prosecutors, who have experience using investigative practices that are appropriate in cases involving serious misconduct. This can include questioning techniques that can be crucial when witnesses have a strong interest in denying or minimizing their part in potential misconduct.

The E&I team that conducted the OIG’s investigation of the zero-tolerance policy used about a half-dozen policy analysts—not investigative agents—and did not even have a full-time attorney assigned to the team. The source familiar with the investigation summed it up by telling me: “You can’t really hold people accountable through an E&I review. You’re essentially pre-supposing the outcome—that nothing wrong happened.”

*

The OIG’s report suffers from several other conspicuous flaws that call into doubt the seriousness and comprehensiveness of the undertaking.

The lengthy delay to its completion—two-and-a-half years after the policy had nominally ended and less than a week before the end of the Trump administration—is hard to fathom. NBC News reporting suggested that the delay may have been because “there were people inside the Justice Department who really didn’t want this report to come out,” but other investigators of the family separation policy had managed to work far more quickly: inspectors general at the DHS and the HHS issued reports critical of their agencies, and congressional Democrats completed two reports on the policy, even as they noted that Trump officials, including some at the Justice Department, had obstructed their inquiries.

It is hard to believe this was entirely unintentional, given Horowitz’s track record during the Trump administration, which was marked by aggressive inquiries into areas of interest to Trump and congressional Republicans (Comey, McCabe, Hillary Clinton, Carter Page) and by slow or nonexistent investigations into areas of justifiable concern on the part of Democrats, including leaks to damage Hillary Clinton and to discredit the Trump-Russia probe, the FBI’s investigation into Brett Kavanaugh, and much else touching senior Trump DOJ officials. It was no surprise that Horowitz escaped the administration’s May 2020 purge of inspectors general.

In this case, the report’s ultimate conclusion—that Sessions and his team “failed to effectively prepare for, or manage, the implementation” of the zero-tolerance policy—is, at best, incongruous and, at worst, nonsensical, since there is no morally defensible way to “effectively prepare for” and “implement” a program that is designed to traumatize children. At best, we are talking about degrees of awfulness.

The factual account provided by the report is also focused almost exclusively on that small group of senior officials—Sessions, Rosenstein, Hamilton, and the five US attorneys along the southern border—while others who participated in crucial discussions get the benefit of anonymity. According to the source familiar with the office’s investigation, one of them was an official in Rosenstein’s office named Iris Lan, later nominated by Trump to be a judge, though never confirmed. Another is Chad Mizelle, a lawyer who participated in a critical planning session in December 2017 while working in that same office; shortly thereafter, Mizelle moved to the White House to work on the policy. (Neither Lan nor Mizelle, who now works at the law firm Jones Day, responded to a request for an interview.)

Career prosecutors are also almost entirely absent from the report even though their participation in the policy was integral, since someone at the Justice Department had to stand up in court to represent the government in all of the underlying criminal cases. Career lawyers are not supposed to be automatons. They have ethical and legal obligations to report suspected impropriety—even if those concerns would have fallen on deaf ears at the time—precisely because they may be the last line of defense to it. It is entirely possible that a coordinated opposition among a large group of career prosecutors along the border could have stopped the policy early in its tracks.

Whether and to what extent these prosecutors actively supported the policy or simply went along with it to keep their jobs is relevant but no excuse. According to a report from The Guardian, one career prosecutor objected to the policy during its pilot phase in the El Paso area, and he was reassigned—thanks to an intervention by Lan in Washington. The OIG’s report does not mention this episode. Indeed, perhaps the most shocking and dispiriting feature of the OIG’s report is that it does not identify a single instance in which anyone involved, at any level in the department, objected to or raised concerns about the policy on grounds that it was inhumane or liable to cause harm. No one in the report expresses regret for their participation or even accepts responsibility for their part in the policy’s implementation.

The document is, in sum, a staggering catalog of bureaucratic deflection and blame-shifting among senior Trump DOJ officials.

Gelernt, from the ACLU, is keeping an open mind for the moment. “We’re beginning to get a handle on where all the political people were, but I don’t think we have all of it, and I certainly don’t think we know where all the career people were and who was pushing back and who wasn’t,” he told me. The OIG report “scratched the surface,” he added, but it is “critical that the public at large understand what happened, and how it happened,” including how career prosecutors navigated what he acknowledged may have been a difficult choice to complain internally—or perhaps even to resign. “What I hope is that if they stayed, they were pushing back,” he told me, because it “should have been clear” that the policy “was illegal” and it “should have felt morally repugnant.”

The source familiar with the OIG’s investigation commented: “I don’t understand why the civil servants didn’t push back more than they did.” Then they reflected: “The system is designed to keep people from pushing back.”

*

The Justice Department’s ability to do its job properly relies on the honesty of its employees, and the OIG is supposed to facilitate that through a logic of deterrence—by censuring employees who demonstrate a “lack of candor” when speaking with investigators and, in serious cases, by referring their conduct to criminal prosecutors. There was a particularly strong imperative for an accurate factual record in this case—to prompt internal reform, to provide public accountability and congressional oversight, and, above all, to afford some measure of justice for the families who were separated—but the OIG’s report comes up short.

Numerous portions of the report suggest that senior Trump DOJ officials—particularly Rosenstein, Bash, and Hamilton—were not completely honest with investigators. According to the source familiar with the office’s investigation, officials within the office even debated whether one or more of them should have been referred for criminal prosecution for making false statements.

Rosenstein, for instance, initially told the office that “he was only generally aware of the El Paso Initiative and that concerns related to family separations did not come to his attention until the spring of 2018,” but “that he believed Bash and the other US Attorneys would have ‘flagged any issues that arose.’” The OIG provides the subjects of its reports with the opportunity to review drafts and to comment prior to their completion, and after Rosenstein reviewed a draft of the OIG’s report—which makes clear that the El Paso program was, in fact, a disgraceful mess that had drawn criticism from judges and defense lawyers—he then suggested he’d been actually misled, telling the office that he “recall[ed] hearing about this El Paso program that had been a great success.… I didn’t personally study the El Paso program, so I didn’t know whether it was a success or not.”

Rosenstein also initially told the OIG that he “wouldn’t have asked for assurances” from the DHS about its ability “to manage the children who were entrusted to them,” “because I would have assumed that they have appropriate systems in place.” After he reviewed a draft of the report, he added: “I just wasn’t involved in the formulation of the policy, and [as] it was under way, I was getting reassurances” from DHS “that I now believe to be wrong.”

Rosenstein initially told the OIG that the coordination between the DOJ and the DHS had been “tremendous,” that it was “unlikely that ever in American history has there been more coordination about enforcement,” and that “[t]his was not an issue that was just left to the field.” After he reviewed the draft, he revised the extent of how tremendous things had been: “Rosenstein distinguished between the high level coordination that occurred between the Attorney General and the DHS Secretary with the lack of ‘operational coordination’ that occurred prior to implementation of the policy.” In other words, subordinates were to blame.

There are equally striking instances of inconsistent or implausible claims by Bash, the US attorney for the Western District of Texas who was sworn in in December 2017, shortly after the end of the El Paso pilot program. But perhaps no one comes off worse in the report than Hamilton, Sessions’s adviser and his leading proxy in developing and implementing the zero-tolerance policy. Based on the OIG’s account, the best that can be said about Hamilton is that he sincerely did not care what would happen to the children, but like Rosenstein and Bash, the details of his account are also hard to take seriously.

Hamilton, for instance, told the office “that ‘our understanding’ at the time the zero tolerance policy was issued was that the prosecution and sentencing of family unit adults could be completed in an ‘afternoon’ and that defendant-parents would be reunited with their children shortly after being sentenced to time served, without a prolonged separation from their children.” The claim is ridiculous on its face given the mechanics of how criminal cases work and flatly contradicted by information that the policy’s leaders received at the time.

The OIG’s mild criticisms of the principals involved in the family separation policy have made it easy enough for these figures to stay largely out of public view since the report’s publication. Sessions was virtually impossible to find until Reuters managed to track him down in early March, when he told the outlet that it was “very unfortunate…that somehow the government was not able to manage those children in a way that they could be reunited properly” and that “it turned out to be more of a problem than I think any of us imagined it would be.” Neither claim is credible given the information per the OIG’s report. Rosenstein, who works at the law firm King & Spalding, also did not return a request for an interview for this article, and Hamilton declined through a lawyer. Rosenstein’s senior deputy at the time, Edward O’Callaghan, who also refused to be interviewed by the OIG, now works at the law firm WilmerHale and did not return a request for comment. Bash today works at the large law firm Quinn Emanuel, which once worked in opposition to the zero-tolerance policy, but he declined to speak with me on the record.

Bash’s firm did, however, provide me with a statement that said that Bash “took a well-documented stance against family separations”—citing “[a] thorough reading of the OIG report” and “news stories in The New York Times, The Guardian and other major media outlets”—and had “repeatedly raised major problems with it, sought and obtained exemptions for families, and worked to end it.” So far as I can tell, none of this is true. The Times and The Guardian published pieces suggesting that Bash at one point refused to separate children under the age of five—hardly a bold stand even if it had been true—but according to the OIG’s report, all he actually did was tell Rosenstein that prosecutors in the office had declined two such cases, based on an apparent misunderstanding about the Border Patrol’s policy at the time. When Rosenstein told him that should not have happened, Bash relayed that message back without any evident debate.

*

The question of what accountability ought to look like for the family separation policy is fraught, but the Justice Department, the Biden administration, and Congress have several options.

The judge handling the ACLU’s 2018 lawsuit concluded that the Trump administration’s family separation policy “shock[ed] the conscience” and thus violated the parents’ substantive due process rights to family integrity. Lawsuits seeking monetary compensation from the government—asserting tort and constitutional claims—have already been filed, but the standards that apply to such lawsuits are stringent, and the cases could prove difficult to win. The Biden administration could use them as settlement vehicles to compensate victims, in view of the fact that the ACLU’s lawsuit is a class action, but there are challenging policy issues that the government would have to resolve first.

Even if the government ends up financially compensating the families, there remains the question of individual accountability—particularly for the people, including senior Trump DOJ officials, who exercised most authority in executing the policy. Some have broadly suggested that criminal prosecutions should be in order, but however heinous the policy, it is difficult to envision a theory of criminal liability that might plausibly apply under the circumstances.

In theory, lawyers are subject to ethical rules and the supervision of professional bodies, but these are generally slow to act and toothless in their enforcement. And as Stephen Gillers, an NYU law professor and expert on legal ethics who reviewed the OIG report’s executive summary, told me: “Lawyers can act entirely ethically and immorally at the same time. The same act can be ethical so far as lawyers’ rules are concerned and grossly immoral such that there’s no consequences.”

Informal sanctions seem more possible—after all, nothing prevents members of Congress from refusing to confirm these lawyers for future positions, including as judges, and large law firms could opt not to hire them. In practice, even this deterrence is rarely applied. One of the drafters of the DOJ’s Bush-era torture memos is a law professor at Berkeley and a prominent conservative legal commentator; another serves as a judge on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Before the 2020 election, congressional Republicans confirmed two lawyers involved in the family separation saga as appellate judges: Chad Readler, who defended the policy in court, now sits on the Sixth Circuit, and Patrick Bumatay, who worked on developing the policy, is a judge on the Ninth Circuit.

The most potent tools to pursue accountability belong, in fact, to the Biden administration and Democrats in Congress. A far more comprehensive inquiry into what happened at the Justice Department should take place, and it ought to include a searching review of the conduct of career lawyers, as well as of Trump’s political appointees. Horowitz, the department’s Inspector General, in particular, owes the public some answers about how the OIG’s investigation was conducted, why it took so long, and how questions about the veracity of Trump DOJ officials were settled. Whether conducted by the Biden administration itself or by Congress (through a select committee or multiple committees in concert), the scope of this investigation should encompass the Trump White House and should include subpoena power. (Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee have said they will conduct hearings, but that committee already has a hefty workload.) The standard for this inquiry should match the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s report on the Bush-era torture program.

At present, congressional Republicans seem keen to politicize the problems at the border that Trump left behind. Those long-term government failures, which are now the Biden administration’s responsibility to fix, should not distract from holding to account those officials who ordered and organized the deliberate sadism of the Trump administration’s family separation policy. There have to be consequences for this shameful episode in modern American history, and there cannot be bureaucratic alibis for those who freely participated in it. We could call it a zero-tolerance policy.