These days, people who can afford to ponder the questions are asking themselves where and how they should live. There has been an uptick in upper-middle-class urbanites buying property in rural areas where Covid-19 numbers have generally been lower, and, according to a Pew Research survey, about one in five adults has moved or knows someone who has done so because of the pandemic. Telecommuters with means have found rentals closer to nature and those with second homes outside the city have settled in for extended stays. Especially in times of crisis, the compelling pull of simplicity-in-nature—one of the many contradictions in the mythos of America—tends to reassert itself.

I moved to Vermont from New York City not during this crisis, but another, earlier one: the financial tumult of 2008. I was a young college-educated ex-publishing assistant, somewhat disillusioned; with no employment prospects in the city, I was determined to start over elsewhere. I moved to Vermont and got a job working for a local publisher that specialized in books on sustainable living, which was where I was introduced to the work and ideas of Helen and Scott Nearing.

The Nearings’ 1954 book Living the Good Life, about their experience of starting over in Vermont after they left New York during the Great Depression, became integral to my new way of life on the land—just as it had for generations of idealistic young people before me for whom it was a do-it-yourself homesteading manifesto. An enduring American type, the Nearings were writing in the spirit of earlier naturalist-philosophers like Aldo Leopold, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and John Muir. For the Nearings, too, nature offered a place of solace in the face of progress, a respite from the specter of industrialization, and a purity we should work to protect at all costs.

These were just the kind of intellectuals to whom I was looking for guidance: postindustrial but pre-hippie, hardscrabble socialists, looking for an alternative to capitalism.

*

Scott Nearing was born in 1883 to a well-to-do family on the central northern border of Pennsylvania, at the edge of a virgin hardwood forest. His father was a businessman, his mother a stalwart homemaker. Nearing received an elite education and went on to teach at the Wharton School of Business for seven years, until 1915, when he was fired for his increasingly outspoken, anti-oligarchical rhetoric. In 1916, he joined the American Union Against Militarism, was publicly opposed to US involvement in World War I, and for the next two years held a post as a social science professor at Toledo University in Ohio. Two years later, after his teaching contract was not renewed (for reasons undisclosed), Nearing moved to New York City where he became a founding member of the People’s Council, an antiwar organization whose aim was to mobilize workers and intellectuals against Woodrow Wilson’s Preparedness Movement.

Nearing also joined the Socialist Party and became a lecturer at the Rand School, where he lectured and published prolifically against American war recruitment. This outspoken advocacy eventually resulted in a sedition charge under the Espionage Act. (He was found not guilty but fined anyway.) In the 1920s, Nearing joined the Workers’ Party, writing for its newspaper and traveling widely to spread the word of communist potential. After diverging from the party’s adherence to Leninist theory in a piece he wrote on imperialism, though, Nearing was expelled in 1930.

By then aged fifty, blacklisted from academia and unwelcome in Communist circles, Scott Nearing was thoroughly disenchanted with public life. He had recently found new love, however; his much younger partner, Helen Knothe, was an accomplished violinist from a wealthy background. She also had a nonconformist streak, evident not least in her prior romantic involvement with the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti, who taught that the human search for meaning was a fruitless endeavor that limited the possibility of truth as a “pathless land” beyond the self. After Krishnamurti ended their affair, Knothe had made her way back to the US, soon encountering Nearing, whom she had met previously as a family acquaintance, at which point he became her mentor and romantic partner.

During the Great Depression, when capitalism looked to have failed catastrophically and many people were searching for a better way to organize the economy and society, Scott and Helen Nearing pondered a stark choice: leave the US, which they saw as an “ugly, tawdry, and wanton” wasteland, or remain within its borders and, as Scott wrote in his autobiography The Making of a Radical (1972), dig in as “the emissary lives in the midst of backwardness, but is not of it.” Nearing wrote that Americans were “farther from rationality and reality than the inhabitants of any other backward communities” he had seen while traveling the world. This particular American “backwardness” was, in part, he argued, the result of a US national emphasis on war-as-industry.

Advertisement

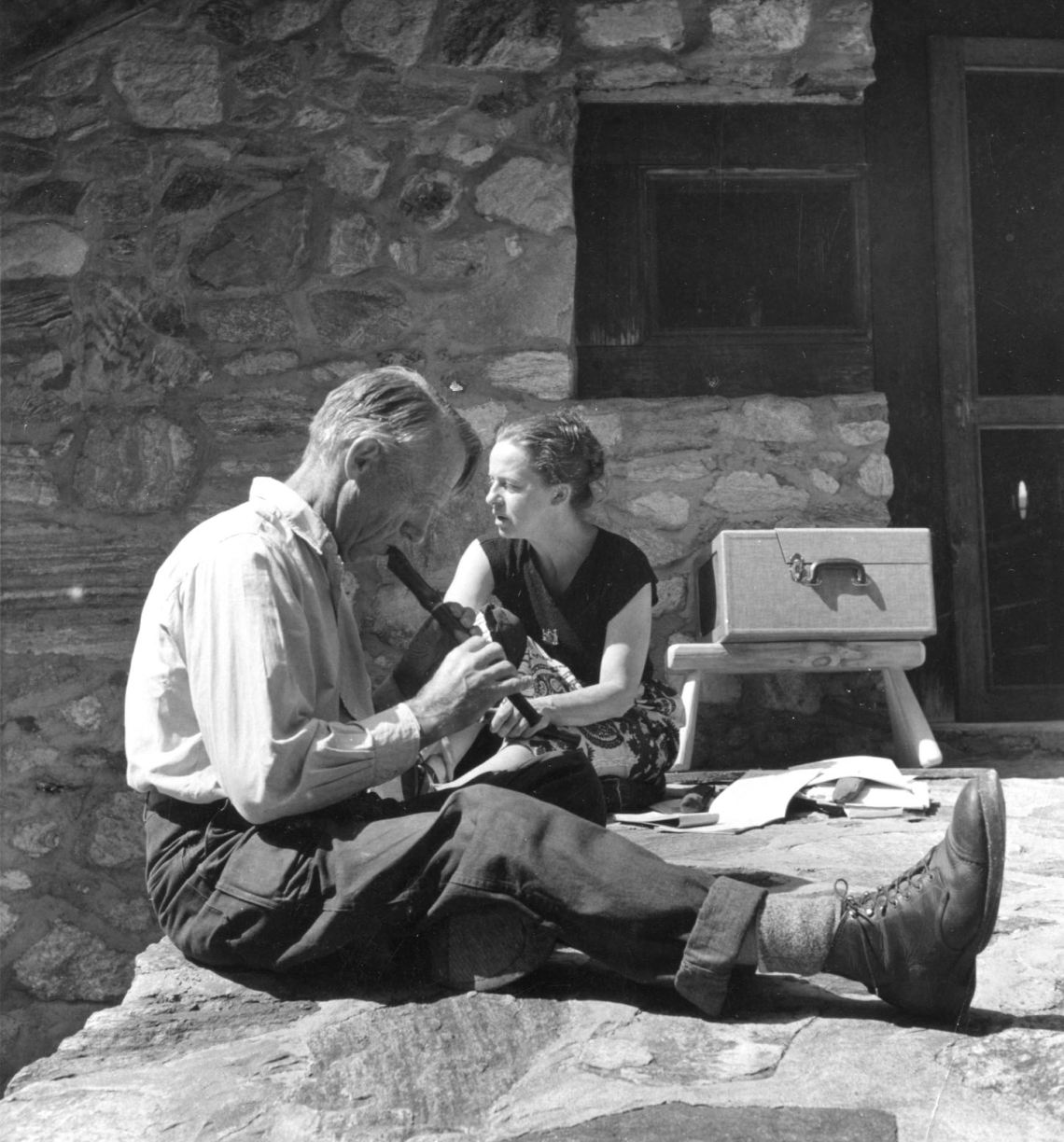

It was 1932, in the depths of the Depression, when the Nearings left New York City. In a self-imposed exile, they bought a rundown farm in an isolated valley in southern Vermont for what would amount to less than $6,000 today; in addition, they took on a mortgage of around $15,000. Inspired by the European chalets of Helen’s family’s Dutch heritage, they designed and constructed a homestead that would soon make them famous, lugging stones directly from the hillside and building it all by hand, with occasional help from neighbors with whom they bartered for labor.

In Living the Good Life, the Nearings related the details of that project along with their decades of simple living, essentially outside the wage economy. Their account recorded both a pioneering approach to subsistence horticulture and a radical revision of work-life balance—decades before that phrase became current. The book also recounted their rigorously simple diet: mostly, they ate only what they grew, out of wooden bowls and with spoons they’d carved themselves. To the extent that they participated in the wider cash economy, they did principally through what they earned from maple-sugaring, which provided enough income to supply their few needs for basic commodities they could not supply themselves, such as citrus fruit, peanut butter, and olive oil. They laid great emphasis on strictly limiting their hours of labor in order to carry on their commitment to reading and studying. As time went by and the Nearings’ experiment grew in renown, a steady stream of disciples passed through, eagerly imbibing the couple’s values and ideas.

The Nearings embraced the parts of gurus and mentors, and wrote about exercising a “sense of social responsibility as teachers, and as members of the human race.” Believing that the entire capitalist order was on the point of collapse, their plan was as follows:

(1) to help our fellow citizens understand the complex and rapidly maturing situation; (2) to assist in building up a psychological and political resistance to the plutocratic military oligarchy that was sweeping into power in North America; (3) to share in salvaging what was still usable from the wreckage of the decaying social order in North American and western Europe; (4) to have a part in formulating the principles and practices of an alternative social system, while meanwhile (5) demonstrating one possibility of living sanely in a troubled world. The ideal answer to this problem seemed to be an independent economy which would require only a small capital outlay, could operate with low overhead costs, would yield a modest living in exchange for half-time work, and therefore would leave half of the year for research, reading, writing, and speaking.

That was the manifesto, but the Nearings’ definition of what they called “the Good Life” contained some glaring contradictions. While possible for “anyone,” they first had to be debt-free and healthy. In practice, they also had to have enough independent means to ensure not only their stable self-sufficiency, but also their capacity to reject what they called a “perverted view of economic principles”—that is, the profit motive. In short, to live without money, you had to have money.

“We were not well-to-do,” they wrote, claiming the virtues of their subsistence lifestyle, despite the guarantee of a future inheritance in their back pockets. They saw themselves as having burned their bridges, and it was true that they had rejected many social norms of their class. On their Vermont homestead, they set themselves apart from the “summer people,” the flush vacationers who came and went as tourists, whom the Nearings saw as parasites preying on local communities, obliging the year-rounders to “sell their labor-power…mowing their lawns and doing their laundry, thus greatly reducing their own economic self-dependence.”

“Such an economy may attract more cheap dollars to the state,” they wrote, “but it will hardly produce self-reliant men.” Self-reliance, that Emersonian ideal, was always their watchword, too.

*

This prolonged projection—seeking distance from what they did not want to identify with, and developing a rationale to support the ethics of that distancing—seemed to supply the central theme of the Nearings’ story. While allowing themselves access to the same class-based system of benefits and privilege that the summer people enjoyed, albeit with the material comforts scaled back, they curated an aesthetics of abstention and renunciation. At the same time, their quest to build a better society retained a philosophical gravitas that appeared to go beyond concerns of their own happiness, and which they could assert as radical social change. Like Tolstoy, whom Scott especially admired, they could live as peasants on their own estate—but proclaim it as a program, too.

As their fame spread, so did demand for the Nearings’ gospel of alternative living. On one occasion, to outfit Scott for his winter lecture circuit, Helen bought an old suit from a thrift store. When an audience member raised a hand to say, I recognize that brand—it’s fancy, Helen responded proudly, I got it for five dollars!

Advertisement

I had similar attitudes when I first came to Vermont, with my dirty boots and torn barn coat. When I met a local at the country store, I thought, we’re the same, we’re neighbors. I considered myself ethically sound, mired in muck, cultivating my gardens and mulching the garlic, making sauerkraut by the gallon—what more could I possibly do for the world, when building topsoil was so time-consuming? I thought about the souls of rocks, of microorganisms. I thought about all the wood we had to get in before dark. Our city friends thought we were radicals in our back-to-the-land adventure—and, I admit, I felt radical.

*

In The Making of a Radical, Scott Nearing described America’s cities as “over-crowded, congested, jostling, frustrating, and hectic…conditions that make a good life all but impossible.” He wanted to get back to the era of what he called “early Americans,” before the industrial revolution, “when most of the people of the United States wrested a living directly from nature…[a] rugged, vigorous people.” A time when, as Nearing wrote, “everyone pitched in and did their bit.”

And yet, the early 1700s were also a time when slavery had been central to the US economy for a century already, making humans-as-commodities the lynchpin of the country’s preindustrial production, a system that would not be abolished for over another hundred years. And while Vermont was an antislavery state, that did not make it a utopia of good intentions and communal fellowship; just ask the Abenaki.

The time Scott Nearing imagines when rugged early America was an ideal community, in which violence and exploitation were unknown, is, at best, a fantasy; at worst, complete delusion. The land was never pristine—wilderness is its own myth—and its indigenous stewards had consistently been displaced and their histories systematically erased so that white American agrarianism could develop. The same is still true today: working-class Vermonters and displaced Abenaki people, as well as immigrant communities, continue to suffer financial hardship and low employment rates, while the wealthy keep coming, bursting with bucolic ideals, setting up a seasonal hammock or selling free-range eggs for next to nothing because, to them, it’s partly a game.

*

Despite its short growing season, Vermont was, in the Nearings’ account, an ideal place to live well. With three quarters of the state reforested by the mid-twentieth century, after the land was first cleared by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century sheep farmers, they describe firewood as a virtually free, renewable resource, and land itself was, in their words, “affordable.” Rather after the manner of the early European settler mythology of feckless natives, the Nearings considered their systems of horticulture and general labor far superior to those of the local farmers, whom they describe working “as a result of accident or whim…appalled by such a planned and organized life,” and instead perfectly willing to stand around and talk for hours with anyone who passed.

In the Nearings’ Good Life, there was no dallying, except during the precise time they allotted for it as a form of cultural exercise. Their ethos was predicated on a strict set of guiding principles “as systematic as though we were handling a large-scale economic project”—as paradoxical as that sounds, since they had no interest in starting a business (nor any need to). Every decision within this model had a rationality based in their rejection of modernity’s alienations. In this, one might discern the paradox of a Protestant work ethic almost Calvinist in its rigidity.

This degree of rigor was crucial, they maintained, to enable self-sufficiency. They were not living to have fun, but to do something important:

We were not seeking to escape. Quite the contrary, we wanted to find a way in which we could put more into life and get more out of it. We were not shirking obligations but looking for an opportunity to take on more worthwhile responsibilities. The chance to help, improve and rebuild was more than an opportunity. As citizens, we regarded it as an assignment.

But improving and rebuilding what, and for whom? Were the Nearings conscientious objectors to a never-ending capitalist war, or were they, in fact, just another type of colonist? Although they report to have worked cooperatively with their neighbors—dividing a syrup harvest in exchange for labor, trading excess when they had bumper crops, even giving away a profusion of sweet peas to whomever should cross their path—it was plain neighborliness, not an economic plan that could be scaled up. Redistribution of that order would have required the good life to become a state-mandated program, which would have changed the definition of it entirely.

*

Reading The Good Life again years later, I did more background research. I found most articles about the Nearings were either hagiographic or crassly critical, calling them out for playing at being poor, and I wondered at times if I was being too hard on them, projecting my own desire to hide behind my “good” choices. And yet, I always felt there was a missing piece, something I had glimpsed but not quite grasped.

And then I landed upon another book Scott Nearing had published, decades earlier, in 1912. In this brief volume, titled The Super Race: An American Problem, he juxtaposed the price of war and the promise of eugenics:

The first step in Eugenics progress—the elimination of defect by preventing the procreation of defectives—is easily stated, and may be almost as easily attained. The price of six battleships ($50,000,000) would probably provide homes for all of the seriously defective men, women, and children now at large in the United States. Thus could the scum of society be removed, and a source of social contamination be effectively regulated. Yet with tens of thousands of defectives, freely propagating their kind, we continue to build battleships, fondly believing that rifled cannon and steel armor plate will prove sufficient for national defense.

Nearing’s anti-militarism, the axis around which his radicalism revolved, was thus rooted in the idea that certain Americans posed a fundamental threat to American society that fighting overseas would not solve. He gave a series of lectures on this theme at Cornell University in 1914, on the eve of the first wave of the Great Migration, when almost two million Black people moved from the Jim Crow South to cities in the industrial North, in search of greater freedom, safety, and opportunity. Similar ideas to Nearing’s about eugenics would soon be applied to justify compulsory sterilization of Black people, over many decades to come, across the country.

Acknowledging the racialized underpinnings of the Good Life is crucial to understanding it. Nearing’s earlier vision of a super race, however, has gone unremarked in the later celebrations of his life’s work. It is unclear, in any case, whether he ever disavowed these supremacist leanings or whether they were simply buried, as if a youthful indiscretion. But once known, this eugenicist framing places a new complexion on Nearing’s pacifism and his binary language about ethical living—and who the implied pioneers would be for a “simple life on the land,” as opposed to one in the “ugly alienated city.”

Scott Nearing was very far from an outlier in his interest in eugenics—indeed, these were consensus views held by many prominent social reformers of the era. Even later, at the very same time that the Nearings were signing on the dotted line of their beautiful new Vermont beginning, a well-heeled, Burlington-based white academic named Henry F. Perkins was introducing the Vermont Eugenics Survey. Created to determine what, or whom, could be blamed for the decline of the rural state, the survey ran from the 1930s to the 1940s in the interest of “community development.” Perkins defined its investigative mission as examining the following criteria:

[The] race descent of the four grandparents (or any other good reference that will give racial position); the place or habitat of the individual inadequate; the sort of land he lives on; the sort of communities in which he resides; how he takes part in social community activities; his occupation, his schooling and training, his pedigree or family history.

Based on this system of classification, the survey found that responsibility for the state’s social and economic problems lay with a surfeit of the “idiot, imbecile, feebleminded or insane.” While there is no evidence of Scott Nearing’s involvement in Vermont’s survey, it is striking how easily language he used could be adopted to define the survey’s purpose of identifying people who lacked “a normal share of vigor, energy, purpose, imagination and determination”—qualities that Nearing identified with New England’s early settlers of Northern European descent, and which he deemed necessary for the Good Life.

The Vermont Eugenics Survey ultimately led to more than 250 sterilizations, most of them performed on women; the number may have been higher because records are incomplete. During this period, members of the Abenaki community commonly went into hiding, often changing their names repeatedly and burning their possessions and personal records for fear of being targeted.

Last month, as the ninetieth anniversary of the Eugenics Survey’s being signed into law approached, a House committee of the Vermont state legislature completed its decade-long consideration of a bill expressing grave regret for the survey and the sterilizations carried out under its auspices. Commenting on the lawmakers’ final push, Chief Don Stevens of the Nulhegan Band of the Coosuk-Abenaki Nation welcomed the apology as a first step: “You have to at least acknowledge that there’s a wound there before it can heal.”

*

Lately, long-stagnant real estate values in Vermont are going up, thanks to a mass influx of upper-middle-class escapees from cities across the US during the pandemic. The rising property prices are a mixed blessing for Vermonters—a windfall for some, who see a possible increase in the tax base, the curse of continued gentrification and another form of erasure for others. These newcomers are now the equivalent to the Nearings’ “summer people,” whereas I’m what is called a “beforeigner.” Now the rural life is newly available to those with remote-working privileges connected by the telecommuter rail. It’s also a form of continued “white flight”—this time, not to the suburbs, but to the countryside.

Along with the wave of back-to-the-land hippies was a generation of radicals and reformers who followed in the Nearings’ footsteps—Sixties leftists like Murray Bookchin and Bernie Sanders, both incomers originally from immigrant backgrounds in New York City who became icons of egalitarian values and social activism, and drew others like them to the state. Their programs were decidedly less individualist, and certainly not eugenicist, but what metric determines the outcomes and impact of social change?

The American tradition of vigor-in-nature rhetoric demands redefinition. Ruggedness is all relative—the working farmers in rural Vermont, whose livelihoods depend on what they grow, live on the land under conditions very different from those who farm as a hobby. In fact, the family-owned farms that once spanned Vermont’s valleys—like those of the Nearings’ neighbors—continue to dwindle in number as the domination of conventional commodity agriculture has made it ever harder for them to make a living. And, of course, there are the Abenaki people, who continue to seek reparations for the land that was taken from them, a wound whose healing demands more than mere acknowledgement. Can the Good Life ever be good unless it is equally accessible for the working poor and the disenfranchised, or indeed anyone other than the wealthy and white?

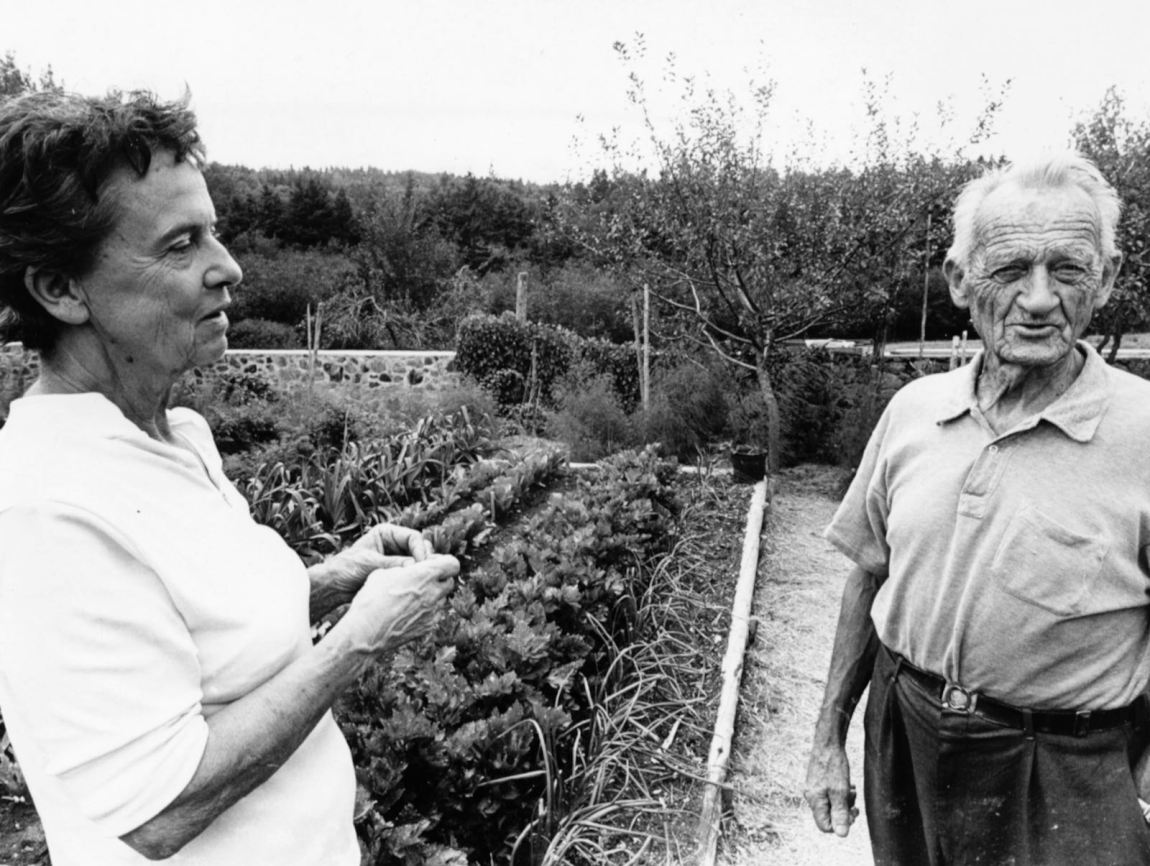

After twenty years of their first rural experiment, the Nearings left Vermont—alienated, ironically enough, by what they saw as the state’s culture of individualism and a lack of collective, cooperative ethos among Vermonters. They moved to rural Maine to start again, and lived out the rest of their lives there, on another hand-built homestead, which overlooked the Penobscot Bay. The next thirty years looked much the same as their time in Vermont, even as the world changed around them. Their homestead is now an informal museum, wooden spoons still hanging on their hooks beside the cupboard.

That second attempt to perfect their rugged, rural vision encapsulated the central contradiction of the Nearings’ radical impulse: to reform society by fleeing from the social. After Scott’s death, Helen Nearing published a memoir called Loving and Leaving the Good Life (1992). In it, she wrote: “The universe is too magnificent as it rolls on to concern itself overmuch with personalities. The greatest thing we can do with our lives is to realize and live in the entirety rather than in our own puny selves.” That sounds like a return to the ideas of Krishnamurti, but you might choose to hear a faint echo of a call to collective action.