Americans born in the two decades following World War II grew up in an atmosphere of prosperity and hope. Between 1945 and 1970, US production of goods and services quadrupled, and much of the country began to take its modern form, with highways, motels and office buildings. By 1971, virtually every American household had a refrigerator, a washing machine, a TV, and a vacuum cleaner; and one in three had more than one car. Sure, there were problems, but wages, especially for manual workers, were rising, some of the worst legal barriers to racial equality were gradually being dismantled, and, at least at first, the futile horrors of Vietnam were not widely known.

But as children born in those years went to work, doors were beginning to close. The trouble started in the factory towns of Ohio, Pennsylvania, and upstate New York, and then spread nationwide. In 1976 and 1977, Bethlehem Steel laid off 3,500 workers in Lackawanna, New York, and 3,500 more in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, tripling the unemployment rate there in just one summer. In tiny Conshohocken, Pennsylvania (population 10,000), Alan Wood Steel laid off about 3,000 people. Millions more good manufacturing jobs would be lost in the coming decades, as factories downsized, moved abroad, or shut down completely. Even if some laid-off workers received severance, they now spent less at local bars, department stores, and other businesses, which soon closed, too, turning downtowns into ghost towns.

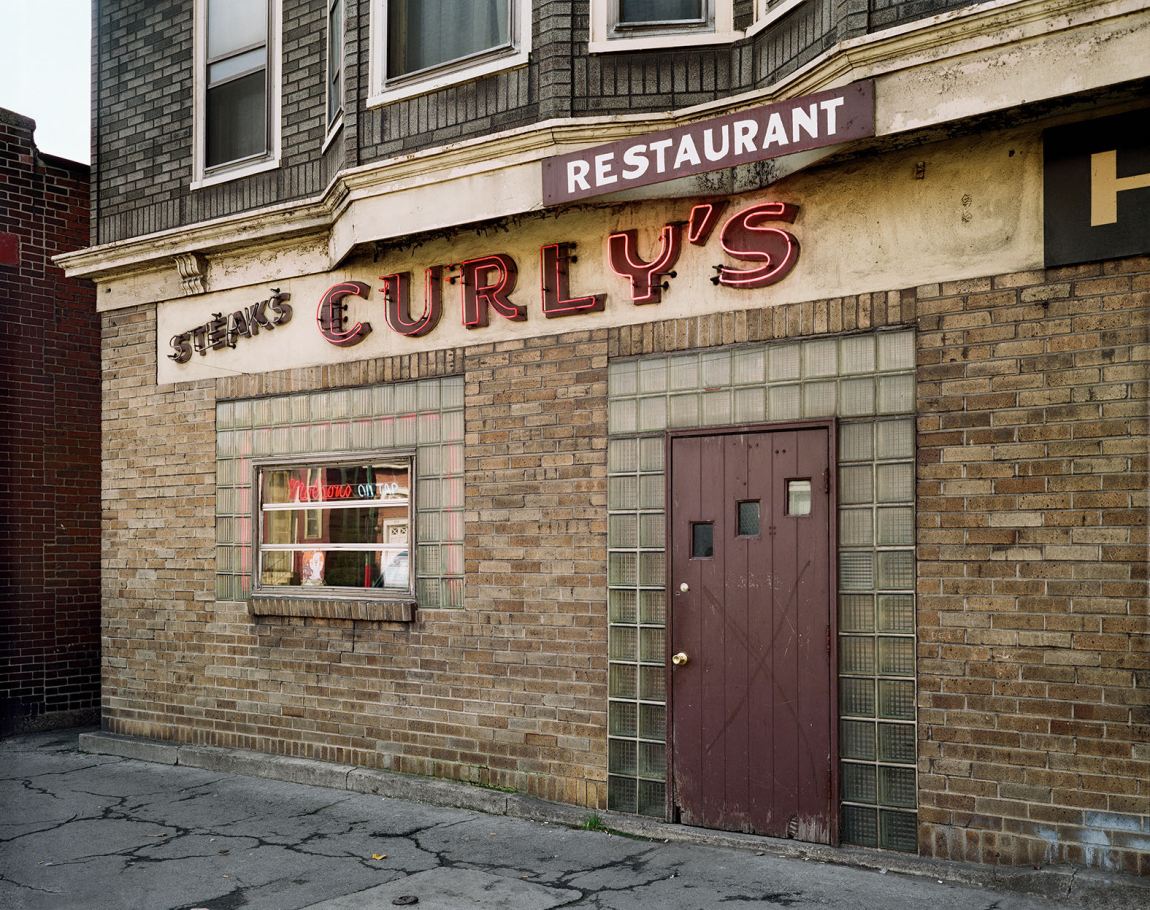

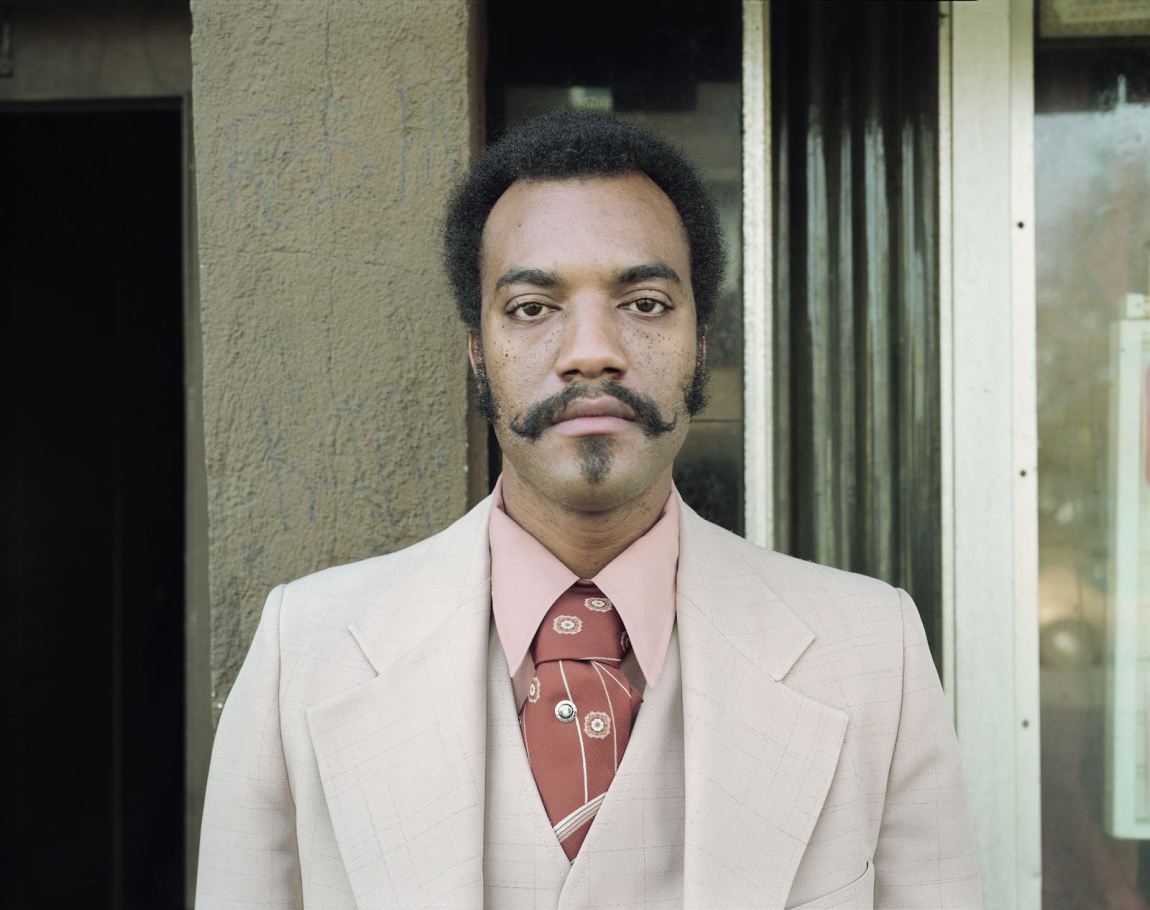

Stephen Shore captured this moment in a series of photographs made during the fateful summer of 1977 to illustrate a Fortune magazine article titled “Hard Times Come to Steeltown.” Shore’s story alludes to the fact that the problems people faced weren’t just material; they were spiritual, too. All calamities cause practical hardship, but some also change how we see ourselves. Slowly, imperceptibly at first, an epidemic of self-destructive behavior took root in these formerly optimistic towns. In the late 1970s, so-called deaths of despair—suicides, drug overdoses, and alcohol-related deaths—began rising among US working-class whites, even as rates of death from those causes were falling in almost all other populations, including college-educated white Americans, Europeans of all social classes, and, after the ravages of the 1980s crack epidemic, among US Blacks as well. By 2015, deaths of despair among working-class whites had risen so high that overall US life expectancy was falling for the first time since the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s.

At first, the people of Steeltown tried to fight back. Many had grown up with the New Deal notion that the purpose of government was to help people with their problems. They staged demonstrations against the factory closings and called on Jimmy Carter’s administration to provide financing and loan guarantees so that at least some of the factories could be saved. What the people of Steeltown didn’t know was that the Democratic Party, which had long defended labor and counted on its support, had undergone a strategic shift.

In 1974, a new cohort of Democratic lawmakers who’d grown up in affluence long after the Great Depression arrived in Washington, D.C. They were keen to get the economy, then staggering under the OPEC oil embargo, moving again, so they jettisoned many of the Democratic Party’s foundational principles, including a commitment to the use of banking and industry regulations to ensure relative economic equality. Unlike their New Deal predecessors, who were vigilant antimonopolists, suspicious of capital, these new Democrats tended to agree with their Republican peers that over-regulation was stifling growth. As a result, Carter began a huge deregulation program that continues to this day, and he did little or nothing to help labor cope with the changes.

Democratic strategists knew the party would pay political costs, but as Matt Stoller writes in his recent book, Goliath: The 100-Year War between Monopoly Power and Democracy, they saw blue-collar workers as expendable, reasoning that they could still cobble together a winning coalition of “African Americans, feminists, and affluent, young, college-educated whites” like themselves. They were mistaken. During the 1980 election campaigns, Ronald Reagan was hesitant even to visit the depressed steel towns of Ohio and Pennsylvania, let alone give a speech there. After all, in 1976, Carter had secured 129,000 votes from just two counties in Ohio’s Mahoning Valley, enabling the Democrats to win Ohio by just over 11,000 votes. But when Reagan arrived in Youngstown, Mahoning Valley’s labor union stronghold, in October, he was pleasantly surprised by the warm reception he received from workers at a Jones and Laughlin steel factory.

“We’re fed up and we’re scared,” one worker told a Washington Post reporter. “Why not give Reagan a chance?” In an impromptu speech, Reagan made no specific promises, but said he wouldn’t forget what he’d seen that day, and he blamed Carter for the problems. The Democratic lead in the Mahoning Valley shrank considerably, and Reagan carried Ohio in November.

Reagan ushered in the merger, the hostile takeover, and more downsizing, none of which helped the people of Steeltown. But he also managed to channel people’s anger away from Wall Street and toward welfare scroungers, crack addicts, environmentalists, feminists, immigrants, and others whom the Democrats seemed to be mollycoddling. Reagan’s Christian allies also promoted a muscular evangelical creed, which encouraged people to look either to powers supposedly higher than government or within themselves for solutions to their problems.

When these workers heard Reagan’s “government is the problem” slogan, it must have resonated deeply. The Democrats were known for spending money, but not on the things that made sense to these struggling workers. As Democrats pushed for reproductive rights, gay rights, and the empowerment of people of color, the working-class whites left behind in Steeltown felt increasingly disenfranchised and voiceless. This deepened racist and sexist sentiment, as if fighting homophobia, supporting equal opportunities for people of color, and defending reproductive rights were a zero-sum game, played at the expense of Steeltown’s inhabitants.

When the Democrats finally regained the White House, Bill Clinton disparaged regulation and labor’s demands, and supported the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization, which shipped more jobs to Mexico and China. He also removed the word “antitrust,” introduced in 1880, from the Democratic platform. Steeltown simmered for the next two decades. In 2016, Hillary Clinton won the Mahoning Valley by a margin of just 3 percent. In 2020, it swung Republican for the first time since Nixon’s 1972 landslide.

As Stoller points out, the politicians of the Progressive and New Deal eras anticipated that this would happen. They knew democracy was incompatible with extremes of wealth and poverty, and they feared that rampant inequality would foster the rise of Trump-like demagogues with fascist tendencies who would promise to smash the nation’s oblivious institutions on behalf of an angry rabble that saw itself as disenfranchised. That’s why Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Delano Roosevelt created policies precisely to counter inequality and went after concentrated wealth with antimerger legislation, the creation of institutions like the Securities and Exchange Commission, and investigations into the anticompetitive tactics of banks and companies; it’s also why they took steps to regulate the stock market, create compulsory licensing of technological discoveries so that small firms could share in the profits, and break up big utilities and banks through the Glass-Steagall Act, among other measures.

The US soon became a battlefield, not just over policies, but over what is true, what is just, what is moral, and even what is real. What Democrats saw as injustice to asylum-seekers, Trump’s supporters saw as justice toward themselves. What Democrats saw as regulations necessary to staunch existential threats to the planet, Trump’s supporters saw as the handcuffs of self-appointed climate-kook vigilantes, whose real aim was to drive away industry and further impoverish them. What Democrats saw as Trump’s attack on democracy, his Capitol-storming supporters saw as a spirited defense of democracy, and so on. By 2020, Trump’s Steeltown supporters were so blinded by bitterness that they failed to notice that even as their candidate demonized Wall Street, he gave its plutocrats a colossal tax cut and them almost nothing.

Most of the photographs in Shore’s Steel Town are eerily depopulated, but the stunned expressions of the people he does capture belie their colorful 1970s outfits and mutton-chop sideburns. It’s as if they’d just been told moments before that they have a terrible disease. Even those who attempt to smile know everything has changed. This is what it feels like to learn that the institutions you thought respected you and spoke for you have turned alien, and your world has split in two.