Not a photography exhibition, strictly speaking, “Photo|Brut”—currently at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City—is devoted to collages, assemblages, and modes of investigation that could be considered “photographic objects.”

Nearly everything comes from the French filmmaker Bruno Decharme’s personal collection of so-called outsider artists. Decharme, a onetime assistant to Jacques Tati, rejects the term “outsider art,” preferring “self-taught” or the painter Jean Dubuffet’s coinage “art brut”—“raw art.” By any name, “Photo|Brut” (the solidus providing an additional brutalist touch) is simultaneously disquieting and uplifting, a monument to human ingenuity as well as evidence of an imprisoning obsession.

Given the Folk Art Museum’s extensive holdings of the twentieth-century writer and artist Henry Darger, it is not surprising that Darger would be well represented. The exhibition’s emphasis on sketches and photographic source material only reinforces the sense of the eminently collectable Darger as an outsider who has crossed over. So, too, Miroslav Tichý, the show’s other prominent figure, whose homemade cameras and the blurry, distressed, hauntingly voyeuristic images they produced were shown to brilliant effect some years ago at the International Center of Photography.

While Darger and Tichý transcend categorization, “Photo|Brut” is organized into four suggestively titled sections: “Performing,” “Private Affairs,” “Reformatting the World,” and “Conjuring the Real.” Enigmatic fixations are ubiquitous, but the last section, padded with vintage “documents” of spirits and UFOs, is particularly notable for evoking pseudoscientific investigations. Far stranger than the psychokinetic photos on display are Horst Ademeit’s numbered, dated, and heavily annotated Polaroids documenting the effects of the invisible “cold rays” he discovered; as are also the photos that Zdeněk Košek clipped from pornographic magazines and “tattooed” with arcane formulae and symbols related to meteorological events.

Sexual content appears all but de rigueur. Indeed, the show may be usefully cross-referenced with The People’s Porn, Lisa Z. Sigel’s recent history of “handmade pornography,” which often involves the repurposing of commercial culture to self-titillating ends. The anonymous “Sex Doll Polaroids” reproduced in Sigel’s book are clearly a form of photo brut, although the only artist present in both book and show besides Darger is the illiterate farm worker Steve Ashby, who used magazine clippings, among other found materials, in his wood-based assemblages.

As well as its share of erotic collages and secret scrapbooks, “Photo|Brut” includes documented endeavors that, however libidinal, go well beyond porn. What manner of sublimation was involved in Eugene Von Bruenchenhein’s adoring photographs of his wife, or in the fifteen elaborate, lifelike, anatomically correct plaster children meticulously fabricated and photographed by commercial photographer Morton Bartlett? The latter are creepier than an episode of The Twilight Zone, while the enchanting (or perhaps enchanted) Mrs. Von Bruenchenhein, staring dreamily past the camera while variously posed as a pin-up, a prom queen, or a Hollywood-style Polynesian princess, is the exhibition’s unavoidable poster child.

If Von Bruenchenhein’s photographs evoke an “innocent” fairy-tale love story, a kindred obsession—German businessman Günter K.’s 267-photo documentation of an adulterous affair with his young secretary—suggests a tawdry B movie. Nor are these the only quasi-cinematic works on view. Another sort of narrative, Mark Hogancamp’s elaborate World War II drama, painstakingly staged in his backyard with Barbie-sized dolls in the fictional Belgian town of Marwencol, was first the subject of a documentary and then a Hollywood feel-good film, Robert Zemeckis’s 2018 Welcome to Marwen.

More than most surveys of outsider art, “Photo|Brut” serves to cast the work of successful art-world practitioners in a new light. Many of the outsiders make self-portraits in costume or, as Hogancamp does, photograph dolls in staged tableaux—work that, by recalling those quintessential art-world insiders Cindy Sherman and Laurie Simmons, critiques the deployment of these aesthetic strategies as a form of successful careerism. (The same cannot be said of Surrealist fellow travelers like the reclusive auto-portraitist Claude Cahun or the disturbed doll fetishist Hans Bellmer, both far closer to Art Brut than Art Cute.)

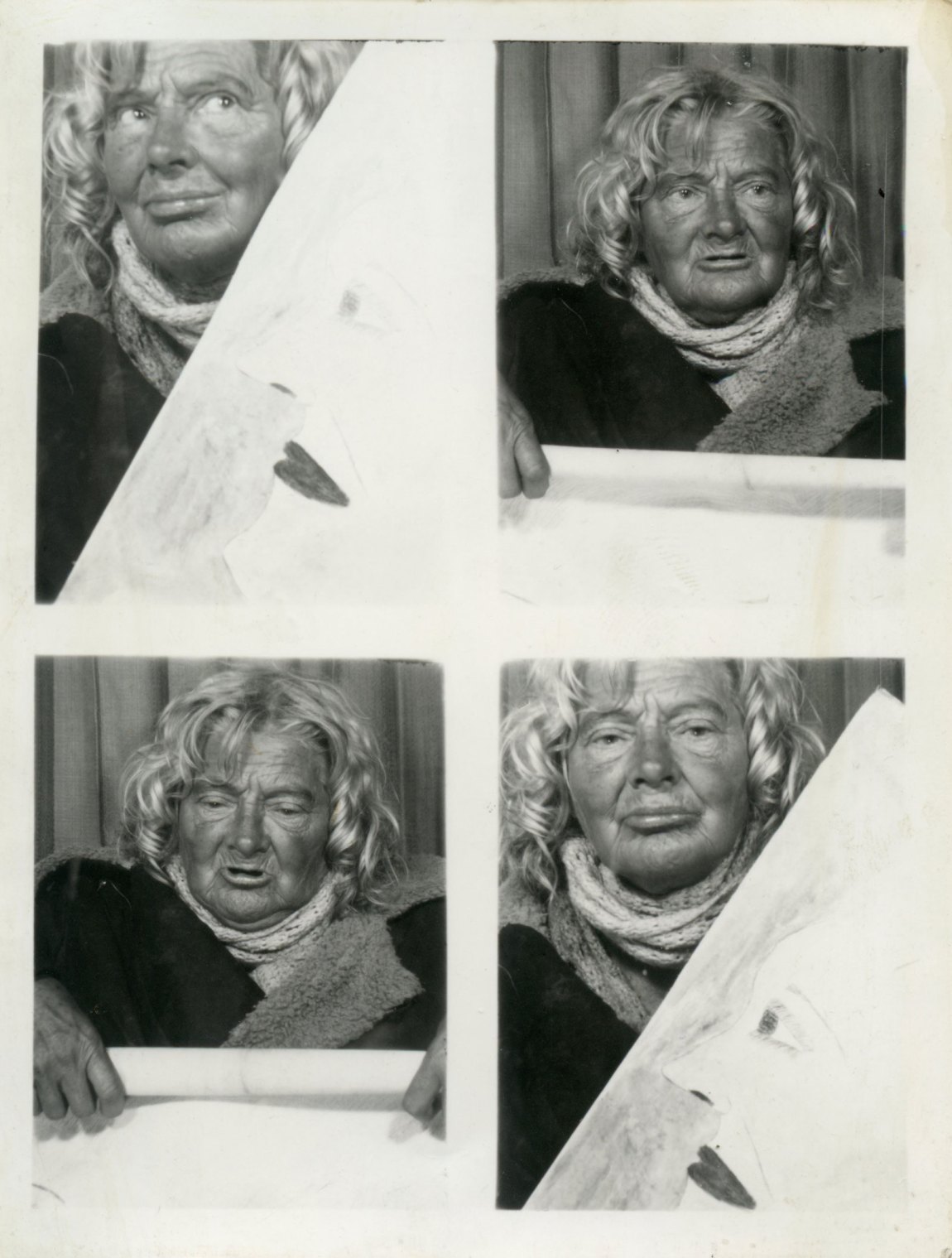

According to their capsule biographies, “Photo|Brut”’s dress-up self-portraitists seem particularly wounded by loss. Marcel Bascoulard, whose mother murdered his father, often appears in the same semi-crouch, dressed in female peasant clothing and staring down the camera like a stubborn child. After suffering the deaths of two children, Lee Godie lived on the street, made self-portraits in a public photobooths, and sold them outside the Chicago Art Institute. Alexander Lobanov, who invariably posed with rifles in his self-portraits, often flanked by similarly armed cameos of Lenin and Stalin, was rendered deaf and without speech at age seven. Tomasz Machiński, Ichiwo Sugino, and Marian Henel were all abandoned children.

Advertisement

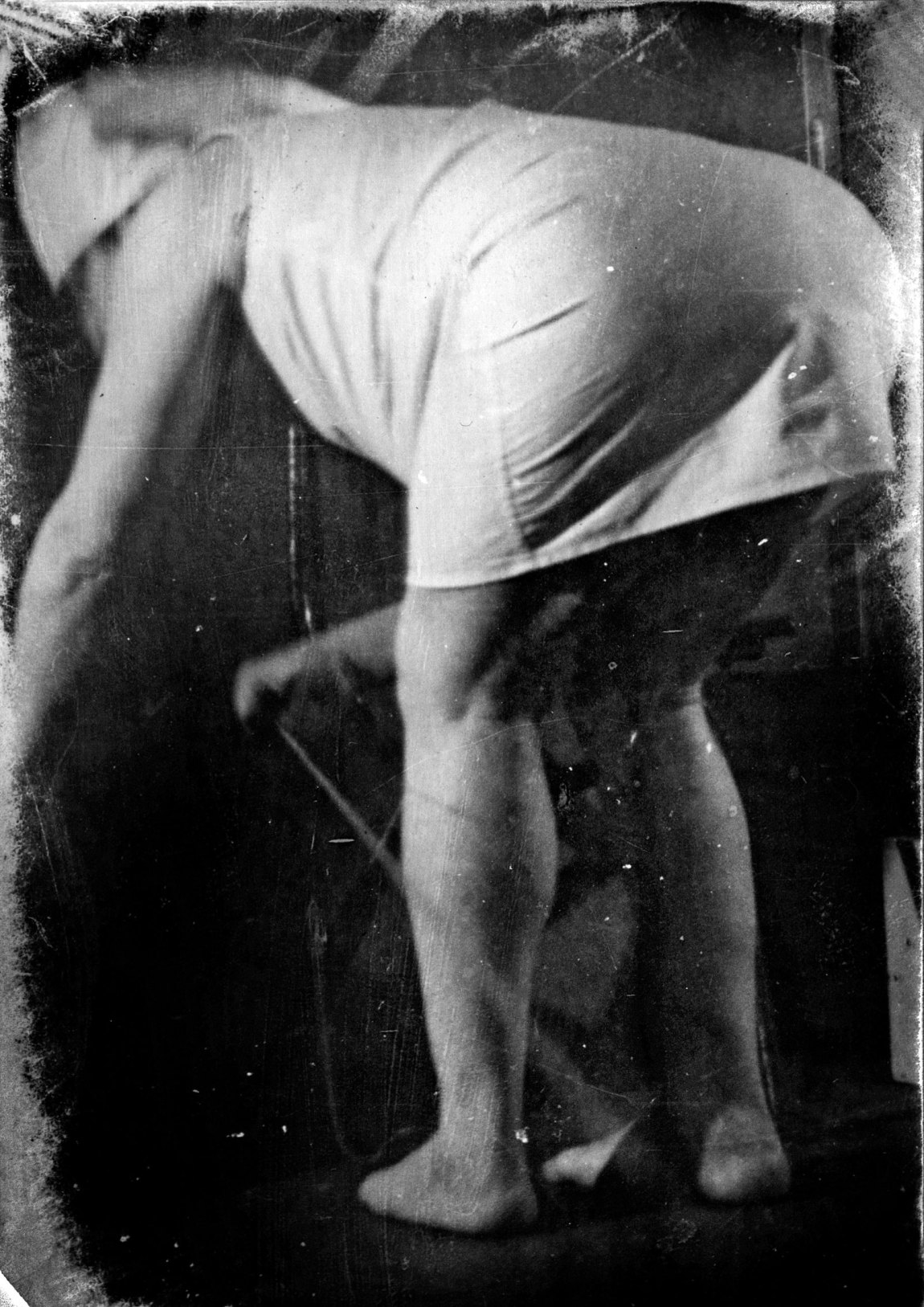

Machiński captures himself dressed as both male and female historic figures, including what appears to be a smirking Pope John Paul II and a snarling Mother Teresa. Largely based on celebrities, Sugino’s alter-ego selfie portraits, posted to Instagram, yield some quirky facts: Quentin Tarantino has more “likes” than Keith Haring but fewer than Freddy Mercury. Hardest to assimilate, Henel’s photographs show him in a white nurse’s shift presenting his butt to the camera, as well as similarly dressed dolls arranged to suggest an amorous tussle between two sumo wrestlers.

Off-putting as their subjects may be, there is undeniable beauty in Henel’s starkly lit, tightly composed images. The function of the aesthetic, the critic Harold Rosenberg wrote in 1970, is “to make a fetish potent outside its cult”—an observation that applies to Henel, Ashby, and the homeless Brazilian collagist Jesuys Crystiano, among others in the show—as well to master assemblagist Joseph Cornell, another Surrealist fellow traveler, not included here, who may be the greatest outsider artist of all (although he has long since been assimilated into the modern art pantheon). Still, art that arises from trauma, magical thinking, and what might be tactfully called mental “difference” (the show avoids diagnoses) can be both more and less than art—less in its naive solipsism, more in its single-minded compulsion.

Much of the work in “Photo|Brut” isn’t primitive so much as it’s primal, derived from a deep psychological or even physiological need. Described as having been a child with “numerous developmental problems,” including autism and hearing deficits, Elisabeth Van Vyve communicated largely through a disposable camera, photographing her surroundings and carefully archiving the images. To ponder these homemade ideograms—carefully framed streetscapes or studied arrangements of ordinary objects—is to be transported back to the caves at Lascaux. They are art before “Art.”