At a cost of $2 billion to the national purse, Prime Minister Narendra Modi is building a monument to himself in Delhi. This revamp of the Central Vista, an architecturally imposing two-mile stretch of British imagination at the heart of the Indian capital, is supposed to symbolize a new, self-sufficient India, finally out from the long shadow of its colonial past. The project involves the construction of a new Parliament building, another set of edifices to accommodate all the ministries, an enclave for the vice president, and, most importantly, a new house and office for the prime minister himself. The land this new development will occupy has been the administrative heart of the country for the entire seven decades of Indian democracy.

The expense is outrageous. It beggars belief when you consider that the project has received a stamp of approval from the same government that hesitates to pay minimum prices to farmers for grain procurement, a government that would not cough up the money to provide transport for migrant laborers who instead tramped national highways on foot during the coronavirus lockdown last year, a government that has now thrown up its hands amid a deadly super-surge of Covid-19 after vaccinating less than 2 percent of the population.

Even before the second wave of the pandemic hit India in March, the country had seen an almost continuous decline in economic growth for three years. The unemployment rate was the highest it had been in five decades. Now, as I write, hospitals in Delhi and all over the country are running out of medical oxygen and even beds. Patients are dying in ambulances teeming outside hospitals or lying on park benches live-tweeting their dwindling oxygen levels. There is not enough space to bury or burn the dead. This is, quite simply, India’s gravest health crisis since independence.

Yet the backhoes and bulldozers are crawling alongside the Central Vista, digging up earth, felling trees. Behind temporary walls of sheet metal, the demolition continues, a public works department official confirmed, even as the city goes into another lockdown and the death count surges hourly. Consider this: at current procurement rates, the entire population of India between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, around 600 million people, could be vaccinated twice for the cost of this landscaping. But instead of doing something about tens of thousands of deaths each day, Modi is doing a renovation.

Aside from its now hideous timing, Modi’s grand projet is pointless but for its symbolic purpose. A scribe in a conservative magazine breathlessly welcomed its ambition to “change the physical face of Lutyens’s Delhi, India’s ultimate power zone.” In another piece, the same magazine characterized Lutyens’s Delhi, a neighborhood of the city named for Edwin Lutyens, the Edwardian architect who built the capital in the image of the British Raj, as populated by “a small elite group of Indians who have spent more than a decade portraying [Modi] in a negative light.” The pro-Modi media has turned such talk into shorthand for corruption in the Congress party, which has had a lock on Delhi’s ministries, and the district, ever since independence.

Lutyens’s Delhi was also a place where Modi was forever made to feel an outsider, denounced by liberal intellectuals for his complicity in the 2002 Gujarat pogrom, when Hindu mobs rampaged against Muslim citizens. Lutyens’s Delhi was a place, the then provincial governor was told repeatedly, he did not belong and would never rise to. Against this elite, he pitched himself as a not-one-of-them candidate in 2014—and won.

Toward the end of his first term, in 2019, Modi said that his only regret was that he could not make the people of Lutyens’s Delhi his own. But it was these people who found themselves displaced in Modi’s Delhi, not the other way around. Things got done the way he wanted them done. His second term has checked off items that have been on Hindu nationalism’s wish list for decades: the annexation of Kashmir, the erection of a Hindu temple in Ayodhya (on the same spot where Modi’s party had led a mob to demolish a mosque in the 1990s), the erosion of civil rights from India’s non-Hindu citizens. Now, with a rebuilt capital, Modi wants to enshrine these aspirations in concrete, to mark his conquest—much as Europe’s fascists did a century ago, the very movements that inspired Modi’s spiritual mentors in the paramilitary group Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh to envision a Hindu India.

A patch of land that was until recently open to all Delhi’s people, where anyone could go for a stroll on a summer night, buy an ice cream from a mobile vendor and contemplate the prospect of Indian democracy, is being usurped. It will now house high temples of a Hindu state, where vacant-eyed careerists will work with great efficiency for the benefit of the Hindu volk. But Modi’s Delhi has a contradiction at its heart: while claiming to be consigning the colonial past to the museum of history, it is in fact delivering the same old imperialism in a new, homemade wrapper.

Advertisement

*

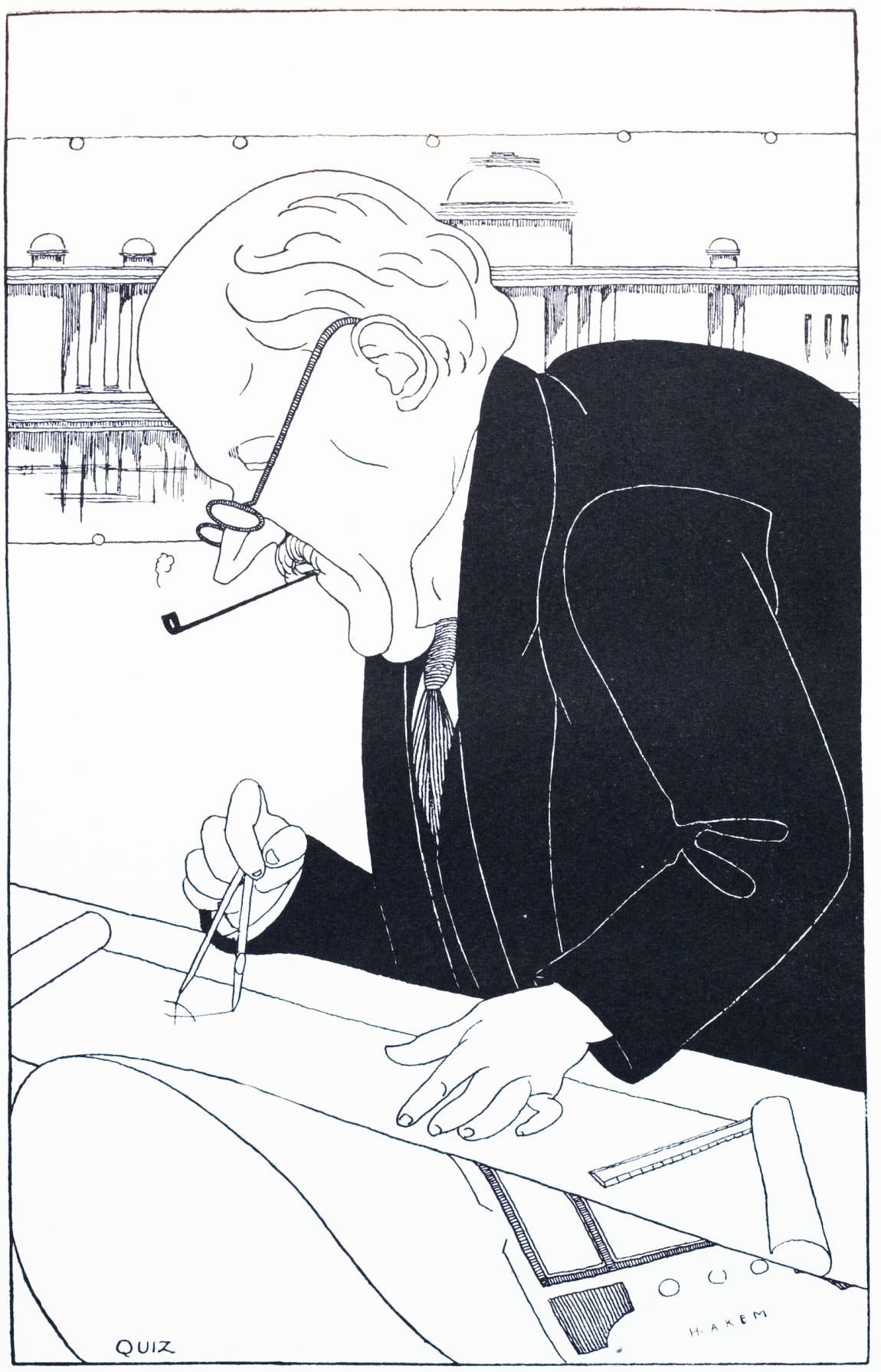

Edwin Landseer Lutyens was the chief architect of New Delhi as the seat of the British rule in India. About a hundred years ago, southwest of the sinuous old metropolis built by the Mughals, he sketched a European cityscape of straight, wide, tree-lined avenues converging on huge roundabouts. The idea was, in the political historian Sunil Khilnani’s words, “to hoist the imperial pennant on Indian territory.”

With extensive use of local sandstone, Lutyens built what the British travel writer Robert Byron, visiting in the 1930s, described as “a scape of towers and dome…lifted from the horizon, sunlit pink and cream dancing against the blue sky, fresh as a cup of milk, grand as Rome.” The cynosure of this plan was the Central Vista, which took in the hexagonal arch of the War Memorial, commemorating the 70,000 Indian soldiers who died for the Raj in World War I, glided west on the Kingsway boulevard, with great lawns on either side, and sloped dramatically up a hill, on whose summit stood the Viceroy’s House, with its carved stone elephants, square courtyards, and towering bronze dome.

Two blocks on the hill for the offices of the Raj’s nomenklatura were designed for “government in its highest expression.” Bungalows for the colonial army officers sat, surrounded by plots of parkland, equidistant from one another on either side of the other avenues and interlinking roads. The distance of an officer’s housing from the Viceroy’s House denoted rank. The native subjects were to see in this city, in the view of the secretary of King George V, “the power of Western science, art and civilization.” They were to find themselves awed and subdued.

It was a hollow polis—embodying the order of the rulers, not the presence of its people—devoid of a public square. It made sense for the British to overlook that crucial feature of modern European cities. They were not building a shrine to democratic ideals or inviting public participation in governing. Speechmaking and public assemblies were not part of the theme.

Living beneath Lutyens’s grand dome, Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy, acted on the principle that, as he remarked, “I’m the chap who can’t be wrong—everybody else is wrong.” He governed, as one journalist noted, as “his own public-relations officer,” obsessing about camera angles; and from this residence he presided over the process that led to the partition of India.

Partition meant that several new cities had to be built more or less from scratch. In New Delhi, though, India’s postcolonial rulers settled for changing the nameplates. The Viceroy’s House became the President’s House. The senior civil service blocks on the hill became the offices of the Indian government. The Council Chamber, which had been placed apart from Kingsway—because, after the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms conceded partial self-rule after World War I, the natives were always visiting—became the Parliament House. The War Memorial became the India Gate. Kingsway became Rajpath.

What newly independent India chose to retain was more than merely cosmetic: emergency powers that the colonialists had used against pro-independence fighters were retained in the Indian constitution. The carnage that followed partition hung in the air of the halls where the Constituent Assembly framed the constitution; looking at the mayhem in the streets, the debaters agreed that the state had to be powerful to maintain order. The citizen, again, had to be kept chained by the colonial rulebook.

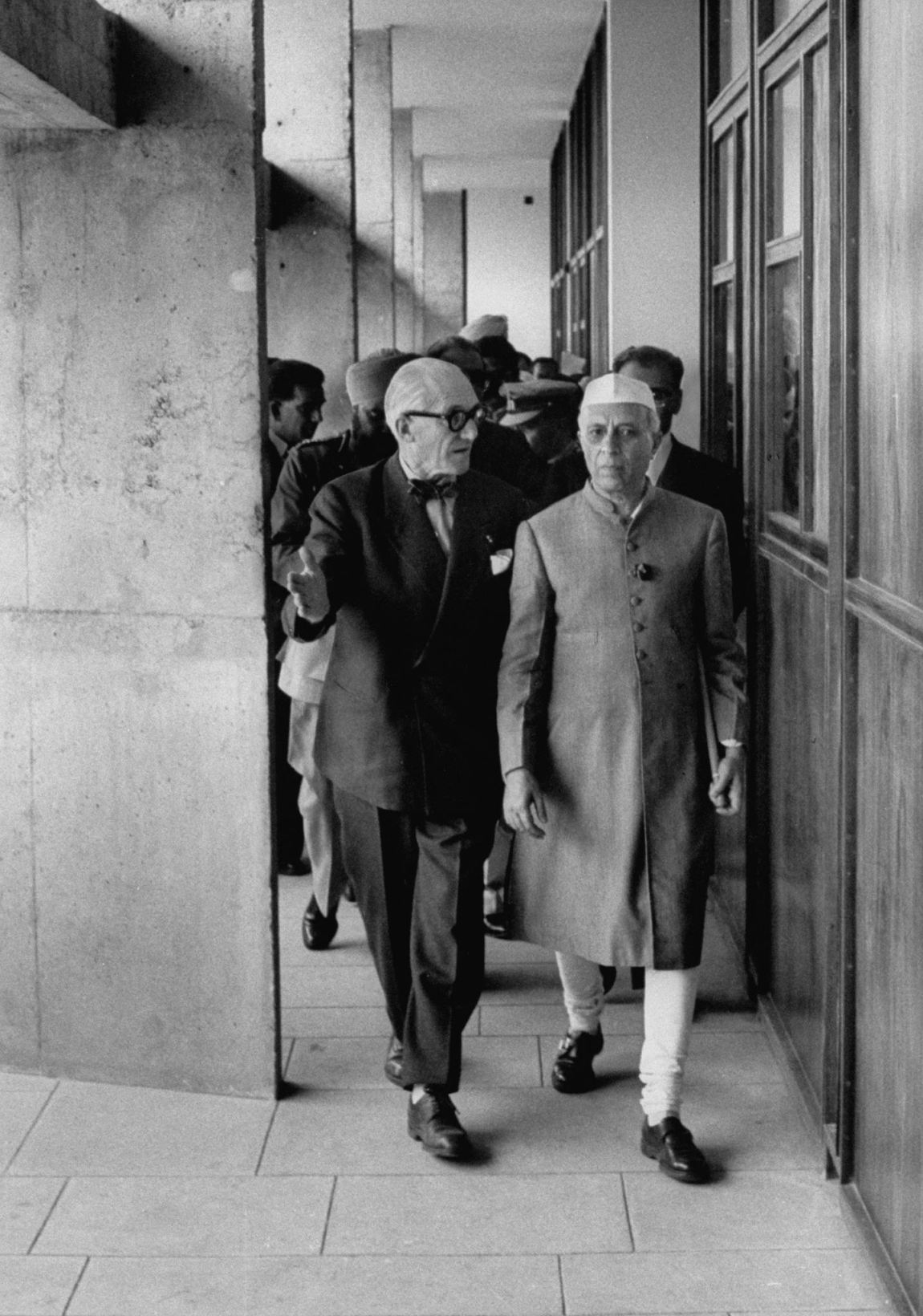

But Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, wanted an architectural showpiece of his own. He wanted the provincial capital of Punjab, Chandigarh, to compensate for the beauty of Lahore, lost to India as the capital of the new state of Pakistan, and to symbolize “the freedom of India, unfettered by the traditions of the past.” Accordingly, in 1950, he dispatched two bureaucrats to the rue de Sevres in Paris, where they solicited the services of Le Corbusier.

Corbusier at first told the pair that he could design the city sitting right where he was. But as the negotiations went on, Corbusier grasped that this was an opportunity to see his utopian plans not just entered for competition but, for once, fully realized: “It is the hour that I have been waiting for—India, that humane and profound civilization.”

Advertisement

When, a few months later, Corbusier arrived in India, he went to Chandigarh via Delhi, with the imperial hauteur of Lutyens’s Delhi etched in his mind. There, before even surveying the land in Punjab, he designed a new master plan for the city as if on a whim. One of his collaborators recounted:

Corbusier held the crayon and was in his element. “Here is the station,” he said, making a dot. “Here the commercial street,” and he drew the first road on the new plan of Chandigarh…. “Here is the head…Here is the stomach…Here the city-center.”

This was in the same spirit as Corbusier’s doodle sent to an official at India’s embassy in Paris with a note, in which he cast himself as guide and prophet. The city he built was no Ville Radieuse of the future, where residences would be assigned by family size instead of socioeconomic status. Instead, just like Lutyens’s Delhi, it was exclusively a government city, where one’s distance from the Assembly building was—and still is—a marker of one’s social status. The trees that line the sidewalk were not native species but transplanted from abroad. An artificial lake runs beside the city.

Unlike Lutyens’s Delhi, Chandigarh did get a public square at the Assembly, but it never opened to the public. Since the 1980s, when Punjab was beset by a separatist insurgency, its flat cement expanse remains locked away behind gates guarded by armed security personnel.

There was no national ethos that informed the making of Chandigarh—the streets and sectors had no names but alphanumeric identifiers. Decorative features, which were minimal, involved not statues of freedom fighters but Corbusier’s own abstractions, like his male figure of ideal proportions known as the Modulor. It was a city you could airlift and drop anywhere in the world; it had no past, no history. “It hits you on the head, and makes you think,” Nehru said. “You may squirm at the impact but it has made you think and imbibe new ideas, and the one thing which India requires…is being hit on the head so that it may think.”

Ironically, it was Corbu the urban planner who left a greater mark on India than Corbu the architect. The grid pattern of Chandigarh’s layout became the template for several Indian cities designed by the Public Works Department. But thanks mainly to Corbu’s influence, modernist buildings also became a feature of them, most visibly at Ahmedabad in Gujarat—the state often called the laboratory of Hindu nationalism.

*

For a time in the 1980s, Delhi’s Rajpath—the former Kingsway—improbably morphed into the public square that Lutyens had purposely kept out of his designs. People with grievances varied and ever-changing came from all over the country to plant their protest tents on the great lawns of the Central Vista. Ramchandra Guha, India’s most popular historian, wished that he “had the time to walk on Rajpath every day from the first of January to the thirty-first of December, chronicling the appearance and disappearance of the tents and their residents. That would be the story of India as told from a single street.”

In the early 1990s, however, the protesters found themselves banished by decree, consigned to a remote area of the city, so as not to be an eyesore as India opened up its economy to world markets. The Central Vista became once again the exclusive domain of globalization’s new ruling class of politicians, lobbyists, bureaucrats, and liberal intelligentsia, who mingled in colonial relics like the Delhi Gymkhana Club. In the two decades of unceasing corruption scandals that followed the economic liberalization, Lutyen’s Delhi was the zip code of crony capitalism in India.

These were the networks that Modi promised to dismantle in his first election campaign as he crisscrossed the country in a privately chartered plane—never mind that these promises would prove hollow. The Gujurati businessman who funded the flights, Gautam Adani, has been repaid many times over with gargantuan profits since Modi came to power. In the last financial year, his net worth grew faster than that of Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk; he stands to gain still more from last year’s laws removing price controls in agriculture. More than 100,000 farmers have been squatting on the outskirts of Delhi for months to protest the measures. But Modi is not a man to roll back laws once they have been rammed through; taking a step back is too much for his vanity.

This obduracy could also explain why the Central Vista project must proceed and why its funds cannot be redirected into the cash-starved, cratering health infrastructure. Yet, for all the urgency, there is little to be said about the project’s architectural language. Bimal Patel, the man to remake the landscape for Modi, does not have the doctrinaire starch of a Lutyens or a Corbusier. “Bimal’s is a highly negotiated practice,” one of his peers told a reporter. Instead of pursuing his own motifs, Patel makes a point of giving his clients what they want, the way they want it. That is all that matters for Modi, who once criticized a black-and-white rendering of a proposed project as looking “like a barren widow.” “Make it colorful,” he ordered the architects. “Paint it.” And they did.

Patel comes from a family of architects in Gujarat, where, after Chandigarh, Corbusier was courted by the local elite to build in Ahmedabad, to help turn the city into a showcase of global trade and capital. Corbusier’s example inspired the modernist architecture of the city, where Louis Kahn, Charles Correa, Balkrishna Doshi, and Achyut Kanvinde also got commissions. Hasmukh Patel, Bimal’s father, was among them.

It was in the early 1960s that another French architect, Bernard Kohn, first proposed the redevelopment of the Sabarmati riverfront in the city. The project lay dormant for decades, until the beginning of this century, when it gathered steam under Modi, who was trying to rebrand the city of the pogrom into the city of prosperity. Bimal, with a practice inherited from his father and his own caste connections in the political leadership, turned out to be the man for the job. All he had to learn was to color his drawings brightly.

Last year, at a university in Ahmedabad, Bimal gave a presentation of what he plans to do at the Central Vista. By the looks of it, he was hesitant and a little vague, perhaps still feeling out his client’s wishes. The blueprint showed ten new buildings—to my eye, formed in a square though some accounts call the layout “doughnut-shaped”—to accommodate a re-ordering of the ministries currently scattered around Lutyens’s network of roads. There will be an underground metro-link and endless parking lots. The Parliament building will be expanded, the original form preserved, with a thousand new offices for the parliamentarians, presumably in high-rises. The civil service blocks on the hill will be turned into museum space; if the government’s revisions of history in school textbooks are any guide, these are likely to take the form of Hindu propaganda and Modi worship. Modi will not be moving into the President’s House—a new one will be built for him, on what Patel calls a “diamond-shaped plot” near the hill.

No design for this residence has been published to date, but it is unlikely to be a modest dwelling. Since the riverfront project with Patel, Modi has developed a taste for building behemoths: the world’s tallest statue, a six-hundred-foot colossus of Vallabhbhai Patel, Nehru’s deputy and icon of Hindu nationalism; the world’s largest cricket stadium, named for the prime minister, naturally; the longest tunnel in the Himalayan foothills. Patel has also been enlisted to revive the glory of Kashi, the spiritual capital of ancient India, in Modi’s parliamentary constituency, Varanasi. This involves renovation and expansion of several dozen temples in the city, but also bulldozing parts of the most intricate human settlement imaginable and offending the locals, for whom every inch of the land there is sacred. But the scorned residents of Varanasi should take solace in knowing they are better-off than those who were displaced permanently to make way for the riverfront development and Patel colossus.

The Central Vista, too, is protected by a long list of environmental and heritage laws, as well as the norms set down in Delhi’s decades-old master plan. These are being overridden: neither Patel nor Modi has bothered with process or legality; neither citizens nor conservation experts have been consulted. Yet the Supreme Court, the guardian of the rights of the government in India, has blessed the project. It will go on. The National Museum, the National Archives, and several buildings, such as the Vigyan Bhavan, will be dynamited. The Rajpath, reserved for public use since the 1960s, will be for the state’s exclusive use—though there has been no admission of this to date. Even that informal public square will be permanently abolished. Instead, Patel promises cafés.

Of course, there is a language to mask this destruction and appropriation; you hear a lot of technocratic talk. “Anybody who’s trying to make administration work more efficiently will see the need for having appropriate infrastructure,” Patel said in an interview. “The kind of synergies that you get from everybody being in one place, from having a standardized infrastructure…anybody who has run large organizations knows that you need the infrastructure.”

If the Central Vista project sounds like the new headquarters of a multinational corporation, a controlled, centralized environment with closed-room meetings and periodic televised addresses from the CEO, that’s because it is. This is the corporatized, national-populist dream of the future, quite different from Nehru’s independent-modern quest. To paraphrase Khilnani, Modi’s ambition here is to hoist the saffron pennant on the dome of Indian democracy. It is an imperializing fantasy, as supremacist and subjugating as the Raj’s, with a more garish aesthetic.

The government has declared the Central Vista project an “essential service” during the current lockdown, so that the migrant laborers can continue working during curfew hours. These are the same people who had walked hundreds of miles on foot to get to their villages during the last year’s lockdown. Now, they are making their way back to the cities to find work, and already feel trapped. Some of them, toiling on the Central Vista, are earning less than twenty dollars for a week’s work; others are worried about catching the virus and dropping dead. They are terrified of the news coming from back home, from hospitals, from crematoriums.

These are the anxious hands constructing the emperor’s palace, as funeral pyres billow smoke in the sullen Delhi sky around them. It won’t stop, for Modi, too, is sure he’s the chap who can’t be wrong.