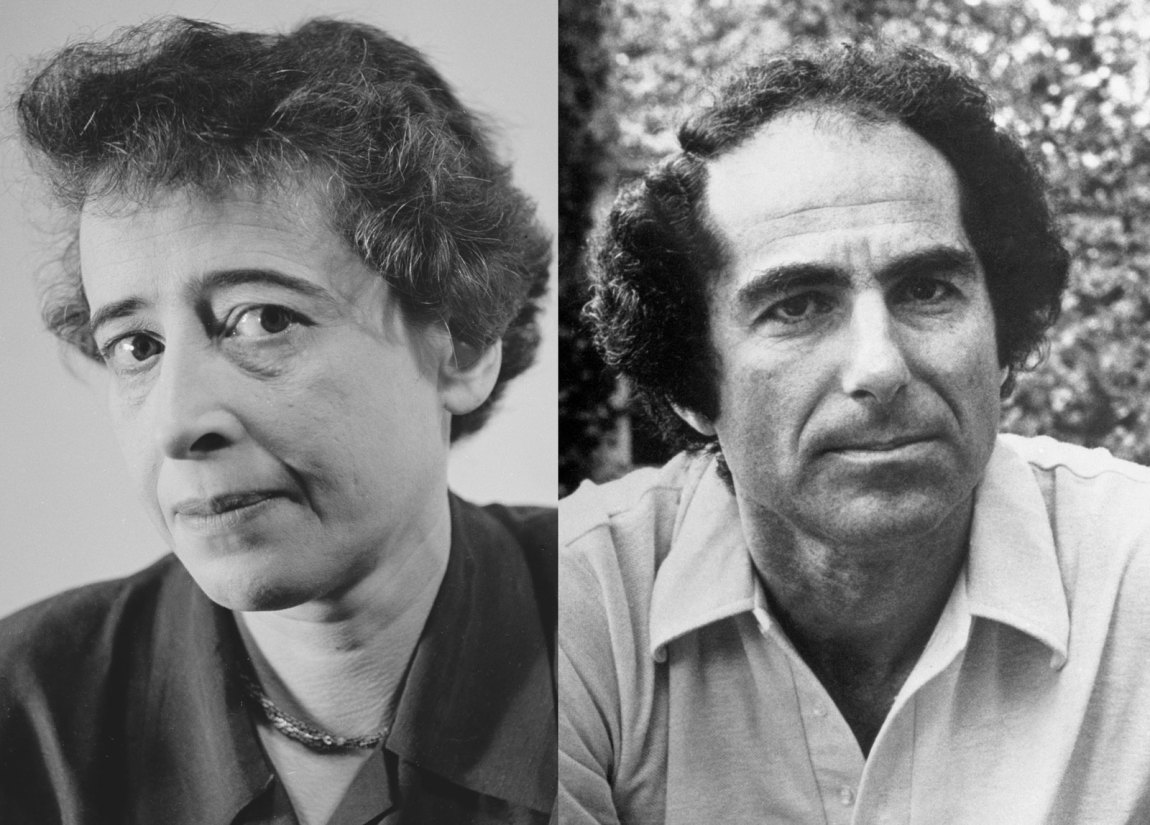

In 2014, the mystery writer Lisa Scottoline wrote an instructive essay for The New York Times about two undergraduate seminars she took with Philip Roth at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1970s. One of the courses was the literature of the Holocaust. Hannah Arendt was on the syllabus.

In his five-page discussion of those years at Penn, Roth biographer Blake Bailey makes no mention of this course or Arendt. Instead, he focuses on the other course, “The Literature of Desire,” and Roth’s erotic presence inside and outside the classroom. In the wake of the allegations of sexual assault and inappropriate behavior that have been made against Bailey, the omission may seem small or slight. Yet it is telling. As Judith Shulevitz argues in a searching analysis of the allegations and the biography, Bailey is as incurious about Jewishness as he is about the reality of women. When the two come together in the form of Arendt, his interest seems, well, nonexistent.

The result is a life stripped of one of its vital currents. Arendt was a real presence for Roth, and the unexpected convergence between their biographies and concerns, particularly regarding Jewish questions, is as uncanny as the doubles that populate Roth’s novels.

The difference between the two writers is obvious. She was born in Germany in 1906; he was born in Newark in 1933. She fled Hitler and never looked back; he fled his parents and kept going home. She wrote The Human Condition; he wrote Portnoy’s Complaint.

Yet, throughout the postwar Jewish ascendancy in America, as other writers and scholars eased their way into the conversation, Arendt and Roth distinguished themselves—not by stirring up the little magazines but by contending with the Jews. Summoning the anxious wrath of a still vulnerable community, Roth and Arendt occupied a singular position: defending the margin against the marginalized, refusing the political pull and moral exaction of an embattled minority. Today, at a moment of rising anti-Semitism and increasing polarization, when the tendency, even among writers and intellectuals, is to circle the wagons in defense of team and tribe, their shared archive of heresy among the heretics pays revisiting.

*

That we even know of that archive is because of the work of another Roth biographer, Ira Nadel, in a little-noticed article in 2018. The story begins in August 1963, when the Princeton sociologist Melvin Tumin grumbles in a letter to Roth about the fact that Roth “liked” Arendt’s report on the trial of Adolf Eichmann, which had appeared in The New Yorker that spring. (Roth’s respect for Eichmann in Jerusalem seems not to have faded across the years. When she was in her twenties, the author Lisa Halliday had a relationship with a much older Roth, which she turned into fiction in Asymmetry. In the novel’s first section, which is set against the backdrop of the Iraq War, the Roth-based character tells the Halliday-based character, “If you want to learn about the Holocaust I’ll show you what to read.” One of the three books he recommends is Eichmann in Jerusalem.)

Eichmann in Jerusalem set off a furious reaction upon its publication. For her alleged soft-pedalling of Eichmann’s anti-Semitism and her criticism of Jewish leaders who cooperated with the Nazis, Arendt was vilified as a friend to anti-Semites and an enemy of the Jews. In the view of her critics, Arendt had not simply written a flawed book; she had revealed her bad character. She was a cretin and a criminal—heartless, vain, wicked, meretricious, cruel. The savage tenor of the campaign against her, which extended from the Anti-Defamation League and the World Jewish Congress to The New York Times and even Partisan Review, to which she’d been a longtime contributor, was captured by the words used to describe the controversy: her allies compared it to a pogrom, her antagonists to a civil war.

We don’t know what drew Roth to Arendt’s writing on Eichmann, but we do know that he, too, was unsettled by the question of Jewish collaboration with the Nazis. The “moral horror” of it, he said, “excited my imagination.” In 1959, Roth wrote a television play, “A Coffin in Egypt,” for NBC. He based the story on Jacob Gens, the Jewish head of the Vilna ghetto whom the Nazis deputized to make the monthly selection of a thousand Jews for the death camps. According to Bailey, Roth wrote three drafts of the script. He imagined Montgomery Clift for the part of the Gens character, whom he named Solomon Kessler. NBC paid Roth four thousand dollars, but decided not to move forward with the production. Slated for NBC’s Sunday Showcase, the play would never hold its own against The Ed Sullivan Show in the network’s ratings war against CBS. The material was too fraught.

Advertisement

The horror of collaboration, for Roth and Arendt, was not simply that it forced Jewish leaders to assume the power over life and death; it was how those leaders draped their power in biblical garb and endowed it with religious meaning. According to Arendt, Chaim Rumkowski, who headed the Jewish Council of the Łódź Ghetto, styled himself as an ancient Jewish king. People called him Chaim I; he “issued currency notes bearing his signature and postage stamps engraved with his portrait.” (In 1942, after the Germans demanded that the children of the ghetto be prepared for deportation, Rumkowski instructed their parents: “Hand them over to me! Fathers and mothers: Give me your children!”) In Roth’s script, Kessler and a rabbi conduct a Talmudic dialogue with an elderly Jew whom Kessler has chosen for deportation:

KESSLER: Do you want a thousand, or ten thousand!….You! On the train!…

OLD MAN: What did I do? Why—

KESSLER: I don’t know what you did! You lived a life—come on! Come on!….

OLD MAN: I’m seventy-eight. Rabbi, who can be buried in a strange place?…

RABBI: “So Joseph died, being an hundred and ten years old, and they embalmed him, and he was put in a coffin in Egypt.” You remember? Joseph himself. Joseph himself had to wait for his sons to carry his bones to the homeland.

OLD MAN: I’m not Joseph, Rabbi. I’m me.

Once it’s clear that the Jews may exact vengeance upon Kessler for his collaboration, a Nazi tells him, “There’s a theory of Freud’s, Solomon, that the Jews themselves killed Moses. Well, you have been their Moses, their deliverer.”

*

Thanks to the decision of NBC, Roth was spared the denunciation of the Jewish establishment. It was a temporary reprieve. Like Arendt, he wound up writing something for The New Yorker that infuriated the Jewish community. “Defender of the Faith” appeared in the magazine in March 1959 and was included in Roth’s prizewinning collection of stories, Goodbye, Columbus, which came out later that year.

Where Jewish collaboration was the question of “A Coffin in Egypt,” the exploitation of Jewish solidarity is the subject of “Defender of the Faith.” That, too, was an Arendtian theme: Eichmann in Jerusalem opens with a scorching sequence on David Ben-Gurion’s using the Eichmann trial, the Holocaust, and the supposedly eternal threat of anti-Semitism to build “Jewish consciousness” and international support for the Israeli state. “Defender of the Faith” is set in a training camp in Missouri during the final months of World War II, after the defeat of Germany but before the surrender of Japan. A Jewish conscript makes spurious appeals of kinship to his Jewish sergeant, complete with references to Hitler and anti-Semitism, simply to gain special privileges and, ultimately, exemption from fighting in the Pacific. Both texts, Eichmann in Jerusalem and “Defender of the Faith,” are haunted by the possibility of Jews’ betraying themselves and their values through the manipulation of Jewish loyalty. In the wrong hands, solidarity can be as perilous as collaboration.

Roth’s defenestration came in 1962, on a panel at Yeshiva University, Arendt’s in 1964, somewhere on West 43rd Street. (Irving Howe, who chaired a public debate on Eichmann in Jerusalem, remembers its taking place at the Hotel Diplomat; the Princeton historian Anson Rabinbach claims it occurred at Town Hall.) Defending the treatment of Arendt, one writer claimed in Partisan Review that she “fared no worse than some critics of the American Jewish community—Philip Roth, for example.” What that treatment looked like was described years later by Judith Thurman:

[“Defender of the Faith”] sparked a violent reaction in certain quarters of the Jewish establishment. Roth was vilified as a self-hating Jew and a traitor to his people who had given ammunition to their enemies by seeming to reinforce degrading stereotypes…. Rabbis denounced Roth from their pulpits, and a leading educator at Yeshiva University wrote to the Anti-Defamation League to ask, “What is being done to silence this man? Medieval Jews would have known what to do with him.”

After the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint in 1969, Roth would be damned by the same holy triumvirate that had condemned Arendt for Eichmann in Jerusalem: Gershom Scholem, Irving Howe, and Norman Podhoretz.

*

In 1973, around the time that he was assigning her work in his classes at Penn, Roth wrote to Arendt that he had been reading “with fascination” her edited collection of Walter Benjamin’s essays, Illuminations. He enclosed his now-famous essay on Kafka, which had just been published in The New American Review. She replied that she had read “with the greatest pleasure” a satirical version of a Nixon speech that Roth had written for The New York Review of Books and joked that she feared Nixon would make use of the speech himself. She added that she was “looking forward” to reading Roth’s Our Gang, which had recently come out in paperback. He offered that “it would be nice to get together with you again” when he returned to New York in the fall. She suggested that he call her then and gave him her phone number (749-5846).

Advertisement

Arendt died in 1975, but that was not the end of Roth’s engagement with her or her work. A 1983 profile of him in People describes “a small but imposing hillock” of books on the bedside table “whose crest consists of a biography of Robert Lowell, Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, and The Jew as Pariah by Hannah Arendt.” In 1987, Roth would make his own trip to Israel where he attended the trial of a Nazi war criminal (John Demjanjuk). Like Arendt, he produced a controversial book from the experience, Operation Shylock, probing the most tender spots of Jewish identity.

In 2018, Roth died. He was buried at Bard College, not twenty paces from the grave of Arendt.

*

While their stories overlap, Roth and Arendt were not doubles of each other. They did, however, write extensively about the double, which they viewed in remarkably similar terms: as an emblem of freedom and enemy of identity.

Initially, the double arouses a great disquiet in us, as the character Philip Roth, in Operation Shylock, discovers upon learning of his imposter. A cousin in Israel phones Roth in New York to say that Roth has just appeared on Israeli television, attending the Demjanjuk trial in Jerusalem. Then a writer friend phones Roth to say that he’s just read in The Jerusalem Post that Roth has delivered a lecture on “Diasporism: The Only Solution to the Jewish Problem” in Suite 511 of the King David Hotel. Roth calls the hotel and asks for Philip Roth. The receptionist yells out, “Hon—you.” A man picks up, and Roth asks him if this is Philip Roth. The man replies, “It is, and who is this, please?” Roth hangs up—just the first of several instances when, instead of affirming his identity as Philip Roth, he exits the stage, allowing imposter Roth to occupy the space, the self, where Roth once stood.

Why does Roth give way like that? In The Origins of Totalitarianism, which was published forty-two years before Operation Shylock, Arendt offers an explanation. No matter what our values may be, each of us is committed to the idea of the uniqueness, the separateness and individuality, of the self—not just our own self but the self as such. So possessed are we by that belief that “even identical twins inspire a certain uneasiness.” We would sooner disavow ourselves than compete with an imposter over the rightful possession of our identity. As Roth admits, had he simply said to the imposter, “Well, this is Philip Roth, too, the one who was born in Newark and has written umpteen books. Which one are you?” he could “easily have undone him.” But that “too” is one too many Roths for Roth, so it is he who is undone instead.

At the same time, all of us are doubles of a sort. Whenever we think, we split ourselves in two. The “two-in-one” of the “dialogue between me and myself,” argues Arendt in Origins and subsequent lectures and writings, is the source of thought and the essence of consciousness. The doubled self allows us the energy of ambivalence, which the belief in the irreducibility of the self precludes. “Always changeable and somewhat equivocal,” this “difference within” enables us to take up conflicting positions and inhabit multiple views. Rife with “ever-changing potentialities,” “this otherness” of the self to itself generates a motion of ideas and perspectives, like those we see in Roth’s best work, from The Ghost Writer to Operation Shylock, in which the character Philip Roth comes to the conclusion, “I will dwell in the house of Ambiguity forever.”

*

Internally doubled, we can never “assume the same definite and unique shape or distinction” that our external self has for other people, says Arendt. That self, the self we present to others or that appears to others, is unified and whole; it hides the double within. The external self is a fiction, a role we perform on the stage. As Zuckerman says in The Counterlife, that self is little more than our “capacity to impersonate” a character in the world. It necessarily involves elements of falsity and fakery.

Whether we think of that self as costume, deception, or untruth, its presentation distinguishes us from other animals. Through such presentation, we oppose ourselves against the fact and fate of the given. Whenever we generate something that is not true or create something that is not there—and that is what the presentation of self to the world is—we enact our humanness. “That’s how we know we’re alive,” Zuckerman says in American Pastoral: “We’re wrong.”

In her pioneering essays, “Truth and Politics” and “Lying in Politics,” Arendt mounts an unusually nuanced treatment, some might say a defense, of political liars. Deception is a permanent feature of political life because it shares the characteristics of political speech and political action. When politicians persuade us to act, they appeal to a reality that does not yet exist (equality, for example), but that they hope our actions will bring about. There is, in other words, a truth-denying and fact-defying element to all persuasive speech and political action.

We find an analogous conception in Roth’s treatment of the double. As the British literary scholar Josh Cohen argues in his authoritative article “Roth’s Doubles,” the Rothian double is a creature of deception because he is a creature of language. Words are “predestined to ambiguity,” Sigmund Freud wrote in The Interpretation of Dreams. That makes language the natural conduit, even incitement, to the fiction-making and divided selves of Roth and Freud (we dream in words; we construct egos and superegos out of and through words).

*

The ever-talking double of the Rothian pantheon is a Jew. Jewish talkiness may be an artifact of theology (arguing with God), an effect of history (wheedling with Cossacks), a residue of Talmudic practice, or the product of psychoanalysis (“say everything”). Whatever the source, there is “inside each Jew,” as one character puts it in Operation Shylock, “so many speakers! Shut up one and the other talks.”

The irrepressible talker is mobilized by Roth against any notion of Jewish wholeness or authenticity, of being oneself, at home in the world. The authentic Jew is the fantasy of the Zionist and the anti-Semite alike. Both get a platform in the “Judea” and “Christendom” chapters of The Counterlife, in which they reduce the Jew to a singular, univocal self. Purged of ambiguity and uncertainty, that Jew has only one destiny: to vacate his diasporic premises and go back to where he belongs, the land of his ancestors, where he will stop talking so much, or at least in so many voices.

Roth’s defense of the double against Jewish reductionism and Zionist certainty is also, in a way, the upshot of Arendt’s strictures about the doubling of the self. The fact that “I am inevitably two-in-one,” she writes, “is the reason why the fashionable search for identity is futile and our modern identity crisis could be resolved only by losing consciousness.” The search for a grounding identity—Jewish or otherwise—necessarily finds its terminus in the stasis of a unified self, unable to carry on a conversation even with itself. Down such a path, she suggests, lies death.

*

Throughout their lives, the identity politics Roth and Arendt contended with most, or at least contended with most cogently, was that of the Jews. (When Roth’s male narrators and characters turn their gaze to women, these threads of ambiguity and ambivalence fray; when they speak about American identity, a sentimental, rank nationalism intrudes. Likewise, when Arendt takes up the question of Africans and African Americans, she gets caught in a thicket of her own, often ugly words.)

Jewish identity politics entailed two moves: first, reducing the Jewish experience to a single story of suffering, the Jew as the eternal victim of history; second, turning that victimhood into the foundation of Jewish existence, creating a ground of permanently extenuating circumstances upon which the Jews might act. When Portnoy complains to his sister, “The Nazis are an excuse for everything that happens in this house!” he isn’t speaking only of his family; he’s talking about the house of Israel.

Roth and Arendt turn the double into a figure of satire and irony, using its destabilizing comedy to deprive that house of its foundations. Roth’s most fanciful double is Anne Frank. In The Ghost Writer, the young Nathan Zuckerman, like the young Roth, has written a story that earns him the accusation of being a self-hating Jew. His accusers include his parents and Judge Wapter, a family friend and respected leader of Newark’s Jewish community. Desperate for exoneration, Nathan makes a pilgrimage to the home of an esteemed and elderly Jewish writer (modeled on Bernard Malamud) who lives in the Berkshires with his wife. There, Nathan meets the writer’s assistant, Amy Bellette. As the evening goes on, the form of Nathan’s redemption takes shape: Amy is really Anne Frank, and Nathan will marry her. What better guarantor of his Jewish credentials? He imagines returning to New Jersey and the conversation with his parents that will ensue:

“I met a marvelous young woman while I was up in New England. I love her and she loves me. We are going to be married.”

“Married? But so fast? Nathan, is she Jewish?”

“Yes, she is.”

“But who is she?”

“Anne Frank.”

According to Bailey, Roth originally wrote the Bellette character as if she were, in fact, Anne Frank. But that simple application of the reality principle prevented him from finishing the book. It was only when he realized that Bellette had to be a fantasy Anne Frank—a fictitious double, conjured from Nathan’s head—that Roth was able to find the comedy in, the meaning of, the story: how an agonistic writer could turn himself into a nice Jewish boy by marrying the nicest Jewish girl that ever lived, how the most sacred figure of the Holocaust—and the Holocaust itself—could be used to resolve the most profane family romance.

Setting out this astute reading of Roth’s Anne Frank in his article, “Roth and the Holocaust,” the UCLA scholar Michael Rothberg shows how the doubling of Frank enables Roth to examine and expose another doubling: the identification of postwar American Jews with the victims of the Holocaust. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, most American Jews sought to distance themselves from the Holocaust. By the 1960s and 1970s, however, the Holocaust had become a useful source of identification, a badge and a shield amid the intensifying racial and ethnic conflicts of a fraying America. Against that instrumental use of Jewish suffering, Nathan—and Roth—insist on preserving the distance between the Holocaust and American Jewry. After Judge Wapter compares Nathan to two of the most notorious Nazis, Julius Streicher and Joseph Goebbels (as Roth himself had been compared by the writer Marie Syrkin), Nathan complains to his mother, “The Big Three, Mama! Streicher, Goebbels, and your son!”

“He only meant that what happened to the Jews—”

“In Europe—not in Newark! We are not the wretched of Belsen! We were not the victims of that crime!”

The most absurd double, for Arendt, is Eichmann. Like Judge Wapter and Nathan’s parents, trying to turn themselves into a version of Hitler’s victims, Eichmann fails as a double. As Arendt observed, Eichmann claimed that he “personally” had nothing against the Jews; he had many “private reasons,” in fact, for not being a Jew-hater. Arendt’s critics have long condemned her for lending credence to these claims. In their eyes, Eichmann was the consummate actor, the greatest double of them all, artfully presenting one face to his would-be executioners in order to save his skin. But such accusations miss the dark comedy of Arendt’s Eichmann. Eichmann, after all, had freely admitted that he knowingly sent millions of Jews to their death. There was no way he ever would be forgiven that crime, even if he could prove that he hadn’t meant the Jews any harm. He was an incompetent liar, a bad double; the only person he wound up deceiving was himself.

Try as he might, Eichmann could never escape his buffoonery. As Arendt noted, he was forever attempting to present himself in one way only to see his double betray him.

Adolf Eichmann went to the gallows with great dignity. He asked for a bottle of red wine and had drunk half of it. He refused the help of the Protestant minister, the Reverend William Hull, who offered to read the Bible with him: he had only two more hours to live, and therefore no “time to waste.”

Arendt pauses to note the hilarity of that last statement: “No ‘time to waste.’” Where the hell did he have to go? His final words similarly betrayed him. Upon stating that he didn’t believe in life after death, he declared, “After a short while, gentlemen, we shall all meet again. Such is the fate of all men. Long live Germany, long live Argentina, long live Austria. I shall not forget them.” Every attempt he made to impersonate one character—the stoic believer in hard truths, the refuser of cheap comforts—was undermined by a follow-up showing that he hadn’t understood his lines. He was not the master of his double.

*

What makes Roth’s and Arendt’s comic treatment of the double so daring and destabilizing, even today, is their willingness to deploy it in the face of Jewish tragedy. As Arendt wrote in a 1944 essay on Kafka, laughter “permits man to prove his essential freedom through a kind of serene superiority to his own failures.” (Kafka, too, was a shared passion of Roth’s and Arendt’s, and like Arendt, Roth saw Kafka as “a sit-down comic” who did “a very funny bit…called ‘The Metamorphosis.’” Kafka influenced the writing of Portnoy’s Complaint, which can be read as a Rothian “Letter to His Father.”)

Comedy is a form of doubling. By creating an alternative self that is removed from a terrible situation, it denies the situation’s hold over us. It also denies the creators of that situation—Eichmann, for example—the grandeur and gravitas they seek. That is why Mel Brooks thought it so important to laugh at Hitler.

Like Brooks, who needed his 2000-Year-Old Man to complete his comedy, Arendt did not think it enough for victims to laugh at their victimizers. They also needed to laugh at themselves, demonstrating their transcendence of, their superiority to, their own flaws and failings. Here, her muse was the German poet Heinrich Heine, who believed that no matter how desperate the circumstances, there was a kind of complicity between tyrants and tyrannized that enabled the wheels of domination to turn. Angered not only by tyrants but also by “those who put up with them,” Arendt writes in “The Jew as Pariah,” Heine turned both figures into “ludicrous figures of fun.” Hence her controversial ironizing of the Jewish leadership in Eichmann.

When asked, in a 1964 interview, about the angry response of the Jewish community to her writing about the Jewish Councils, Arendt didn’t deny the wounds she had opened or the hurt she had inflicted. Nor did she deny her ambivalence about doing so. She refused, however, to back down from her mordant approach to the facts of collaboration. “You must be able to laugh,” she said, “since that’s a form of sovereignty.” This was the classic statement of a powerless people: to see laughter as a kind of sovereignty, a triumph, however momentary, over one’s powerlessness. Oppressed people are funny, the stereotype goes. To the extent that’s true, theirs will always be a comedy not only of the oppressed against the oppressor but also of the oppressed against themselves.

*

If Israel and the Holocaust were the poles of Jewish identity politics in the postwar era, Jews in contemporary America—particularly younger, more progressive Jews—now have a third pole to contend with: Trumpism. The rise of Trumpism, in tandem with the Sanders left, has exploded long-held taboos of Jewish and American politics, allowing Jews, progressives, even some Democrats, to question entrenched beliefs about socialism, bipartisanship, and Israel. At the same time, there is little doubt that Trumpism, with its attending debates about fascism and anti-Semitism, has heightened the anxiety of American Jews and the American left. It has created an atmosphere not identical, but also not dissimilar, to that which Arendt and Roth confronted in the 1960s, when certain types of texts had to pass through a checkpoint and be examined for their help or harm to the “community.”

I first read The Ghost Writer in 1989. A twenty-two-year-old leftist Jew living in Oakland, California, I cheered Nathan’s refusal of the lachrymose conception of Jewish history: We are not the Jews of Belsen! We are not the victims of that crime! Coming on the heels of Donald Trump, today’s twenty-two-year-old version of me is more likely to identify with the response of Nathan’s mother: “But we could be.” Or with the Israeli professor who replied—upon hearing Roth’s claim that “more than fifteen years had passed since the publication of Portnoy’s Complaint and not a single Jew had paid anything for the book, other than the few dollars it cost in the bookstore”—“‘Not yet.’”

The left ascribes this shift to the rise of the Trumpist right. The right ascribes it to the rise of the woke left. The center ascribes it to the rise of polarization. But the truth is, we’ve been speaking in this anxious tense since September 11, 2001, when absolute safety became the name of our desire and we didn’t want the smoking gun to be a mushroom cloud over New York City. Once the argot of our parents and grandparents, “not yet” and “could be” have come to describe the mood of an ongoing moment. (Roth, arguably, made a small contribution to this turn. The Plot Against America, the story of an American Nazi elected to the White House, was published in 2004, at the height of George W. Bush administration, when parallels to European fascism, now forgotten, were running high. In the last year of the Trump administration, Plot appeared as a miniseries on HBO.)

Arendt was hardly unaware of the threat to the Jews. Forced to flee Nazi Germany and then France, she worked throughout the 1930s and 1940s to organize Jewish opposition to German fascism (and then Jewish opposition to Jewish fascism). But she saw how tempting it was to essentialize that threat, to make an unchanging danger and a reductive victimhood the conditions of Jewish being and the foundation of Jewish life. She saw how the possibility of communal harm could be used to make an end-run around the work of moral and political argument, both within a marginalized group and without.

Accused by a rabbi of inciting anti-Semites to hunt Jews as Hitler had once incited the Germans, Roth replied, “By simplifying the Nazi-Jewish relationship, by making prejudice appear to be the primary cause of annihilation, the rabbi is able to make the consequences of publishing ‘The Defender of the Faith’ in The New Yorker seem very grave indeed.” That leap, from text to attack, from thought to deed, did more than skip the mediating steps in between, ignoring the changing politics of power and position of any given moment. It made it difficult to read, and judge, the text outside the light of an enveloping darkness. Additionally, Roth noted:

If the barrier between prejudice and persecution collapsed in 1930s Germany, this is hardly reason to contend that no such barrier exists in our country. And if it should ever begin to appear to be crumbling, then we must do what is necessary to strengthen it. But not by putting on a good face; not by refusing to admit to the intricacies and impossibilities of Jewish lives; not by pretending that Jews have existences less in need of, less deserving of, honest attention than the lives of their neighbors; not by making Jews invisible.

These, then, are the stakes of our moment—not just for Jews or the left but for American political culture. Will we make the possibility of harm the grounding argument of our political life and the measuring rod of our literary judgment? Will we make a reductive victimhood our unchanging story? Will we give honest attention to the variousness of our lives, without solicitude or sentimentality? Will we allow ourselves complexity?