The first thing you see when you walk into “Extraordinary Realities,” Pakistani-American artist Shahzia Sikander’s major retrospective at the Morgan Library, is an Indian Devata dancer, gently resting her knee on the shoulder of Aphrodite. Cast in bronze, nearly life-sized, Promiscuous Intimacies (2020) is Sikander’s first sculpture, and her two women only have eyes for each other. Aphrodite toys with the Devata’s necklace. The Devata curves around Aphrodite like a snake.

The two sex bombs, archetypal respectively for East and West, expose the inanity of the categories. These avatars might be citizens of a single world—one where Alexander’s armies marched through the monsoon-soaked Punjab, where the inhabitants of the Indian city of Nysa claimed Dionysus as their founder, and where a statue of Lakshmi is hidden beneath the lava of Pompeii. Their separation only made sense according to the logic of newer empires. Here in the Morgan Library, they are wrapped together in love. Supremely self-confident and disdainful of all borders, the pair are the perfect guardians for a show in which Sikander blows open the form of miniature painting.

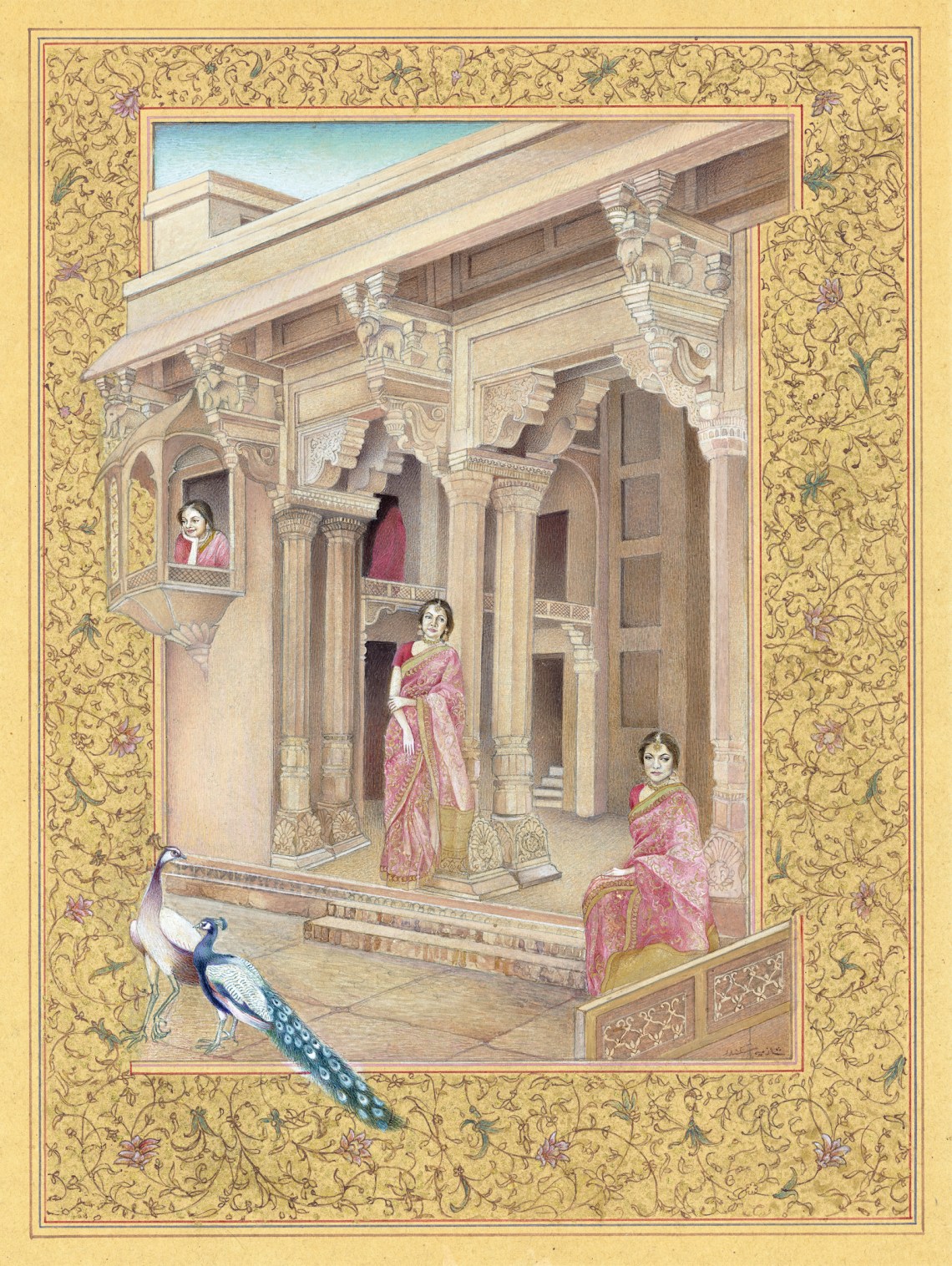

Mughal miniature painting is one of the world’s great visual art forms. First developed by Persian master painters in the sixteenth-century Mughal court, the genre was transformed over the next two hundred years by Indian artists into a medium of impossible refinement, intricacy, and dazzle. Miniature painting is still taught, in all its rigor, at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan, thanks in large part to the intransigent master painter Bashir Ahmed. Sikander was one of his students. So was another Pakistani painter, Hiba Schahbaz. At her studio, and later at the Morgan Library, Schahbaz explained to me the old techniques that students learned from Ahmed and told me what it was like to work under his tutelage.

Even in summer, the rooms had no fans, because fans stir up dust. Students mixed their paints from pigments. They made wasli paper, and brushes from squirrel tail hair. They used seashells as palettes and black tea as stain. Students dipped their brushes in the tea and stroked them on the paper to create subtle layers of brown. Then there was tapai, a technique in which the artist uses a semidry brush to painstakingly lay on pigment and thus create those cloudlike gradations that first drew me to miniatures as a little girl, when I peered into the glass cases at the Metropolitan Museum of Art manuscripts stolen from the countries where they were painted. I knew, even then, that their creators had achieved something I never would. To paint like that required a meditative focus that was miles from my own internal jabber. I felt a sharp longing to be the sort of person who could make pieces as fine as those.

When I was six, hypnotized by the pattern work on Shah Jahan’s saddle at the Met, Sikander was nineteen and had already started the piece that first made her famous. The Scroll (1989–1990) is at once a self-portrait and an endless page from a comic, detailing the prosaic activities of Sikander’s family home. When I saw it at the Morgan Library, I held my face close to the page to follow Sikander’s avatar. In that composition, she appears as a faceless young woman in a ghostly shalwar kameez, a figure who flickers in and out of the many rooms, an observer rather than a participant—which is to say, an artist—until, at last, she finishes painting her own portrait. The Scroll is Mughal in form, existentialist and uneasy in content. Sikander didn’t just copy the greats, but so internalized their grammar that she could use it to portray any room and its tchotchkes in all their particularities, tying the present to tradition, proving the tradition urgently alive.

Like Picasso, Sikander was still a teenager when she mastered her country’s characteristic classicism, and like him, she proceeded to take a blowtorch to the medium. Not to destroy but to redefine, to burn an inky slash mark between the miniature’s past and its future. When Sikander was twenty-four, she moved to the United States to pursue a graduate degree at the Rhode Island School of Design. Two years later, she took a road trip down the Eastern US, from North to South, with a voracious eye for the graffiti that covered not-yet-gentrified city walls. (The graffiti artists Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen later became part of her peer circle.)

Advertisement

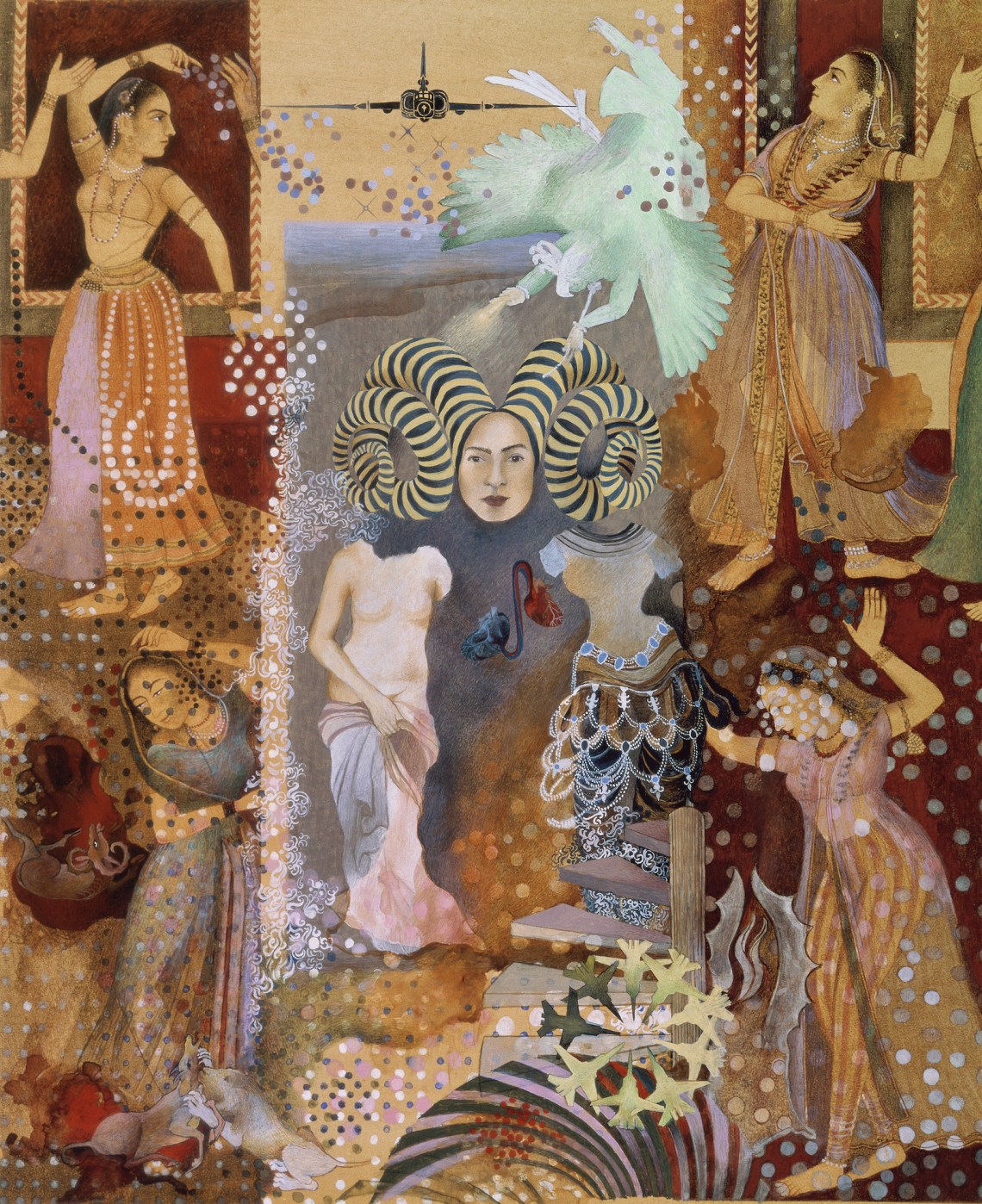

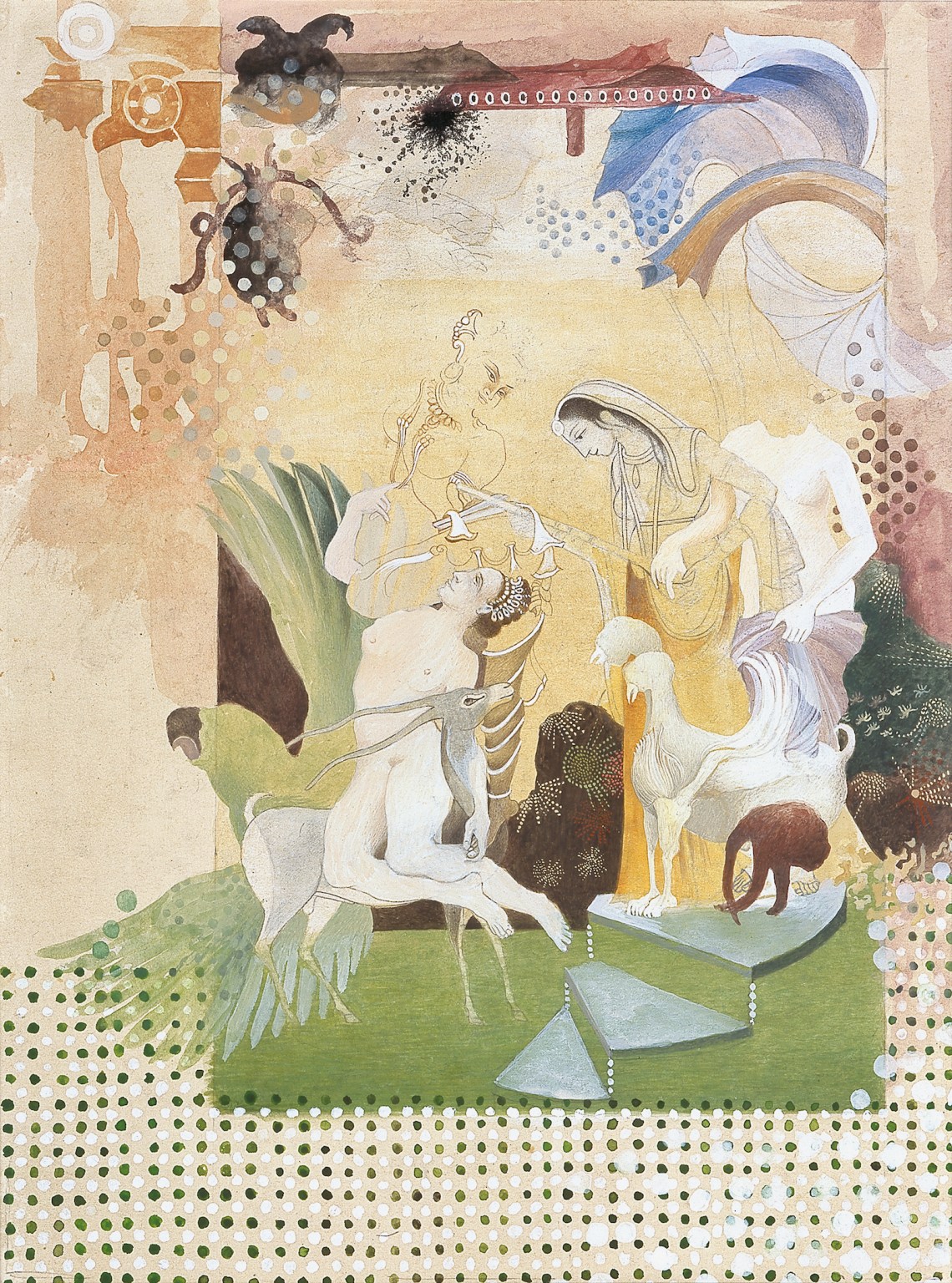

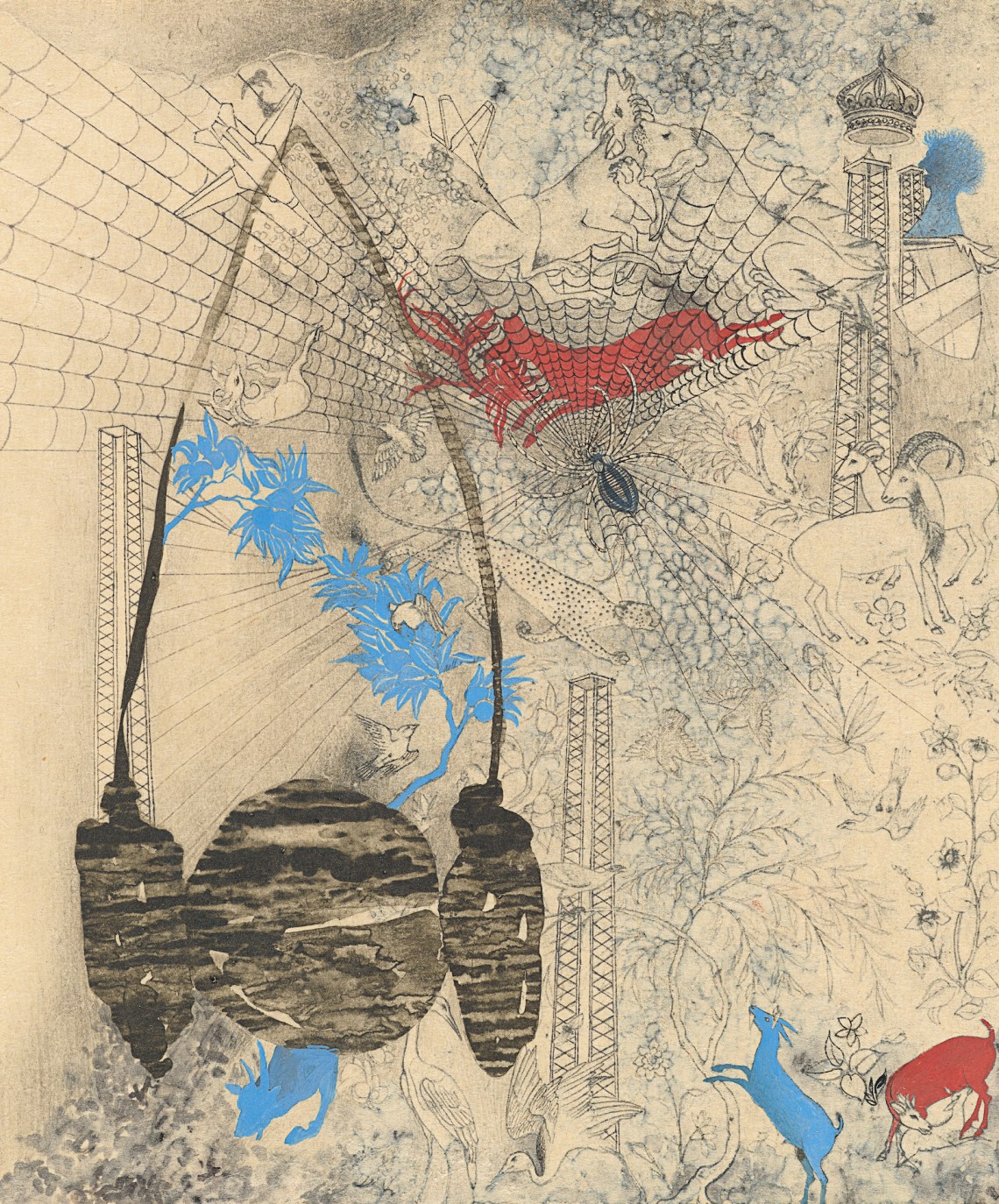

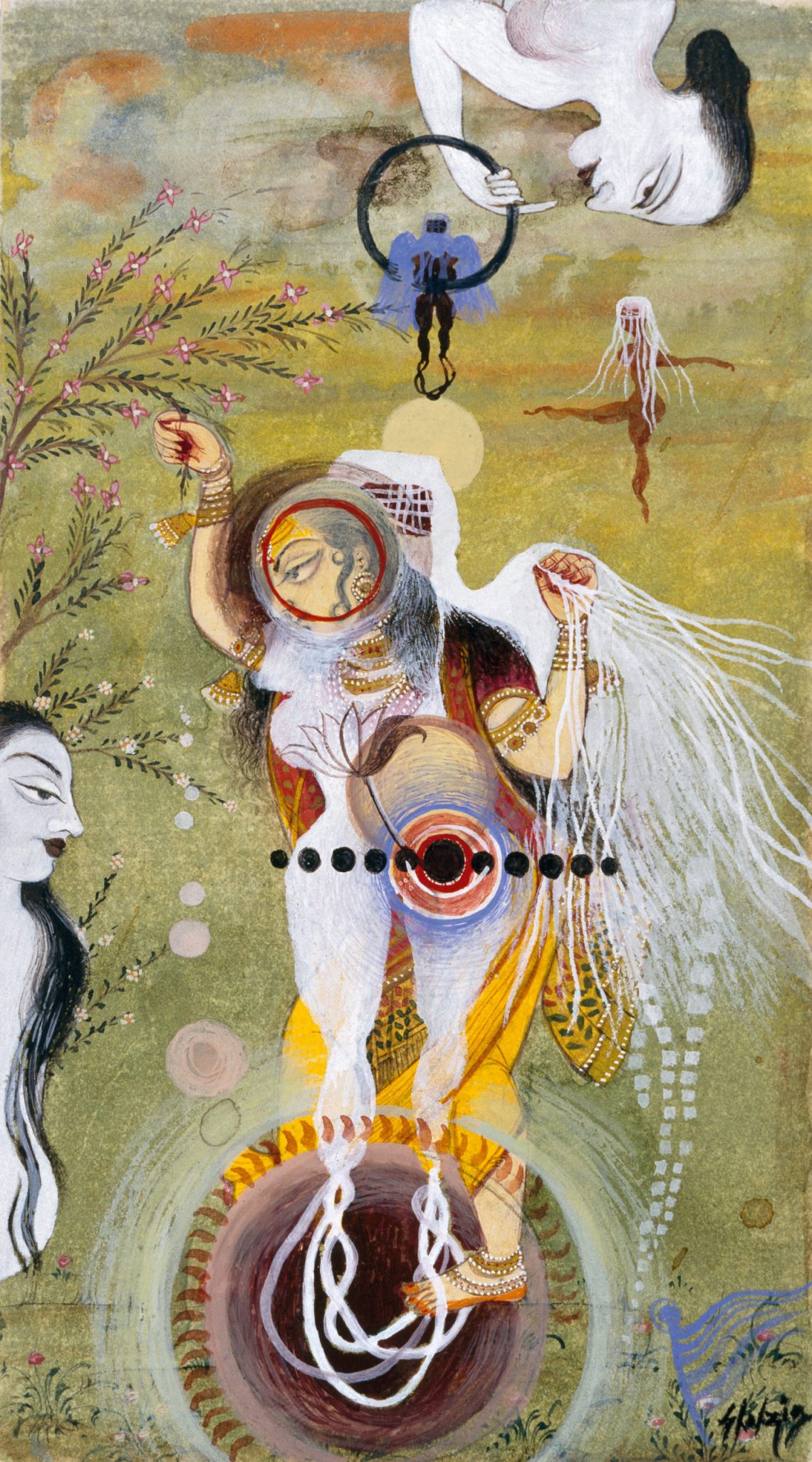

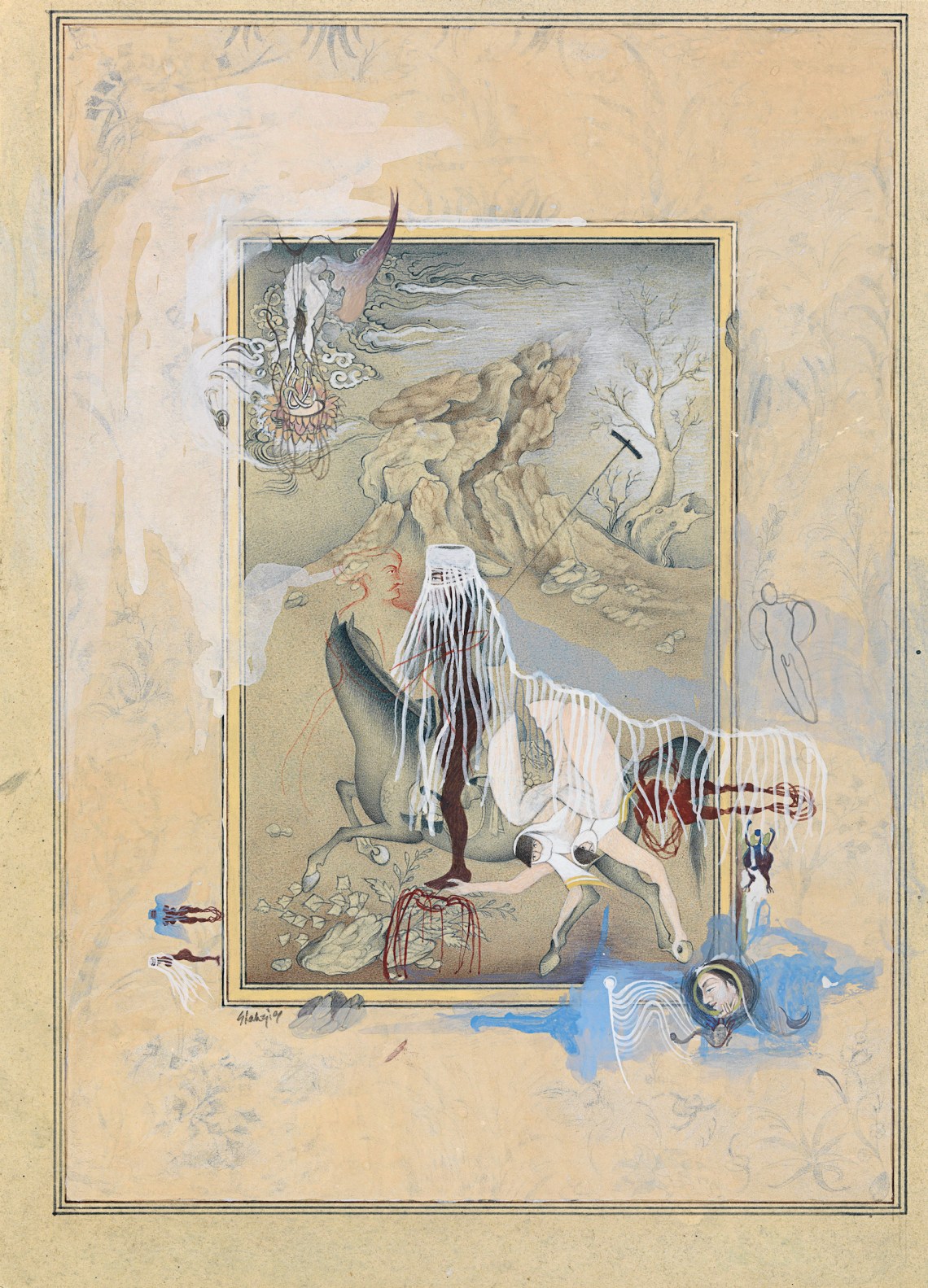

On the neat walls of the Morgan Library, I could see that street-artist swagger. With deliberation, Sikander defaces as she creates: in Dislocation (1995), she layers inkblots on tracing paper as if they’re Rorschach tests; in her animation SpiNN (2003), she ties the braids of gopis (devotees of Krishna) together like the twisted rebar from a demolition site; in Who’s Veiled Anyway (1997), her female figures do not merely dominate the center of the piece but spill over the margins of the image onto the scrubbed but still visible floral border.

“Painting spontaneously over my own laboriously crafted, painstakingly precise, single-hair-painted ‘miniatures’ was an act of rebellion, akin to graffiti,” Sikander told me at the Morgan Library, “in that I was a kick-ass manuscript painter, but I was unafraid to violate the code, the language, the preciousness ascribed to the tradition.”

In this show, the juxtapositions are scintillating. Tantric acrobats. Brooklyn water towers. Horses that resemble the letters of a language that never was. The purported manuscript pages become palimpsests, entries in a sort of Borgesian library or archive, a repository as vast as the Earth itself. Her images invite the viewer down a rabbit hole papered with the detritus of empire, its wars and masquerade balls…

Sikander told me about one famous manuscript, the Shahnamah, or Persian “Book of Kings,” that disappeared from Istanbul’s Topkapı Palace library during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, only to emerge in the hands of a New England glassworks heir named Arthur A. Houghton Jr., who slashed apart, and sold off its pages one by one to realize tax benefits. These pages lived at last in the private collections and museums in Western capitals, far from Tabriz, the city in northwestern Iran where they were created. As in Iran, so in India: “During the European colonial era in the Indian subcontinent, many South Asian manuscripts were dismembered, scattered, and sold for profit in the West, stunting the canon of Central and South Asian pictorial traditions for good,” Sikander said. “Because artifacts and historical paintings from Central and South Asia are scattered in storages of Western museums and private collections, there is always an emerging scholarship around their histories.

“It is precisely this truncated aspect that has allowed me, a visual artist, to take liberty in imagining new art-historical narratives and connections,” she went on. “It was this lack of availability of the actual paintings, objects, the tactile historical work around me while growing up in Pakistan that made me gravitate to digging into the provenance of objects and the archives, the inherent violence in that legacy.” As she said this, I thought of myself, forever going back to the Met to devour those Mughal miniatures.

Despite her early acclaim, Sikander soon grew tired of Western art historians’ and curators’ fixation on her identity as a Pakistani woman, of their ignorance of the feminist traditions she drew upon, and of their assumptions about Eastern repression and Western freedom. This predicament only worsened after September 11, 2001. Suddenly, Sikander found space shrinking for an artist who was at once cosmopolitan and Muslim. Before the al-Qaeda attacks, the law firm Skadden Arps had commissioned her to create a large mural, which was to feature a many-armed goddess who would have been at once pagan, Indian, Islamic, Jewish. After 9/11, all the client saw was the weapons in some of the goddess’s hands. Pressured to alter the image, she withdrew from the project. All that remains is a gouache study, titled A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation (2001). For years that followed, she felt that her work was “glossed over and straitjacketed” by crass assumptions about her identity; as a consequence, she stepped back from the commercial gallery world.

With “Extraordinary Realities,” Sikander stands in her rightful place, just as women stand at the center of her work. In Uprooted Order I (1997), an anonymous angel embraces an Indian dancer. The dancer’s body—or is it the angel’s?—shines through her sari, and she is pregnant with a lotus blossom, black suns, a red dwarf star. Here in the trophy room of a long-dead robber baron, Sikander holds court with a host of rebel queens. Long may they reign.