Storm is the second-strangest book ever written about a storm. The strangest, which has never been published in its entirety, is a memoir by the self-taught artist Henry Darger. At approximately 5,000 pages, The History of My Life was one of the shortest things Darger ever wrote (his first novel, The Story of the Vivian Girls, for which his illustrations brought him posthumous celebrity, was three times longer). Darger begins with an account of his difficult childhood on Chicago’s North Side, his abandonment to the Illinois Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children, and his escape from the asylum at the age of seventeen. Though the asylum is about a hundred miles from Chicago, Darger has no choice but to walk home. Several miles into his journey, two hundred pages into the memoir, Darger is stopped short by a “stupendous and shocking” vision: a great storm racing across the plains. “It had far more wallop than even a powerful atomic bomb,” he writes. “It was a wind convulsion of nature tremendous beyond all man’s conception, immeasurable beyond all man’s conception, immeasurable beyond measure.” Darger’s description of the storm’s reign of destruction across southern Illinois fills his memoir’s remaining 4,878 pages.

George R. Stewart, born in 1895, three years after Darger, commits a similar act of narrative insubordination in Storm, which has sold over a million copies in more than twenty languages since its original publication in 1941. It is commonplace for hack reviewers to credit a novelist with turning an inhuman presence—a house of seven gables, a man-eating shark, the city of New Orleans—into “a character of its own.” But actually to do so, to situate an entire novel on the story of an inanimate, shapeless force, violates a fundamental law of novel writing—that one’s protagonist should have an inner life, or if not that, free will, or if not that, at the very least a consciousness. Though the novelistic form, as E. M. Forster has written, is “tirelessly occupied with human relationships,” Storm’s relationships are only half human, with its center of gravity resting unevenly on the inhuman half.

Stewart credited his inspiration for Storm to an experience that today, some eighty years later, is drearily familiar, at least during our ever-dilating hurricane seasons: reading in the newspaper of a catastrophic storm. He was in Mexico at the time, an English professor on sabbatical from the University of California, Berkeley, and was surprised to find news in the local paper about the large storms of his home state. As he later told an interviewer, “It seemed to me that anything which was so interesting as to be reported to people clear off in Mexico, should have a story in it.” He already had a feel for the subject, living in the Berkeley Hills. “I had watched the winter storm-fronts sweep in from the West with all their majesty,” he said. “No observing person can live in such a spot without becoming storm-conscious.” No observing person can live in the twenty-first century without becoming storm-conscious, but in this, as in so much else, Stewart was decades ahead of his time.

To research the novel, he became a storm chaser, grabbing his car keys whenever a weather report mentioned blizzards or landslides. He rode on a locomotive cowcatcher through Donner Pass and on a flatcar through Feather River Canyon; he stowed away in the engine of a snowplow and toured storm-damaged utility plants. Having been impressed with a storm’s “dramatic values,” he began to realize that a storm “had most of the qualities of a living thing.” “Most” is the workhorse of that sentence, though Stewart committed to his scheme with Darger-esque ardor, deciding that the storm would be not only the novel’s subject but, quite literally, its protagonist.

His heroine is born of a dalliance between northern and southern air off the coast of Japan. After a rapid gestation, she quickly begins to grow, devouring atmosphere. “Like a person,” writes Stewart, a storm “even takes in food, exhausts it of energy, and casts out the waste,” drawing moisture from the ocean and expelling it as rain. A junior meteorologist at the Weather Bureau, developing “a fatherly feeling” for the storm, christens it Maria (pronounced Ma-RYE-a) because he feels that he “must name the baby.” (Inspired by Storm, the National Weather Service would begin naming storms in 1953.) The baby eats and sleeps and makes babbling noises, but it does not stay cute for very long. Soon, it grows teeth.

In her infancy, Maria develops character, a personality, and even something that resembles feeling. “A storm,” writes Stewart, “seems to sheer off from a high-pressure area much as the human hand shrinks from the touched nettle.” Maria even develops an anatomy. She carries herself along “bodily,” sticks out her “long tongue,” and in a single mixed metaphor gains all four limbs: “long arms of rain ran miles ahead.” By the time she debuts on the Pacific Coast, she has left her youth behind; becoming “powerful and sedate in maturity, [she] moved with the steady, sure pace of majesty.” Maria comes to resemble “a middle-aged person who has grown too individualized, not to say crotchety, to fit any rules.” After a one-night stand with a mass of tropical air in the South Pacific, her “eastward bulge” begins to give “a distinct suggestion of mammalian pregnancy.” To the Junior Meteorologist’s grandfatherly delight, Maria delivers a new storm, Little Maria: “‘Why, I’ve known your mother,’ he [finds] himself thinking, ‘since she was a little ripple on a cold front north of Titijima!’” After she expends her vital energies on the Sierra Nevada—her life’s crowning achievement—Maria mellows into a toothless senescence and a quiet death, while her daughter, in search of new thrills, heads east, to New York City.

Advertisement

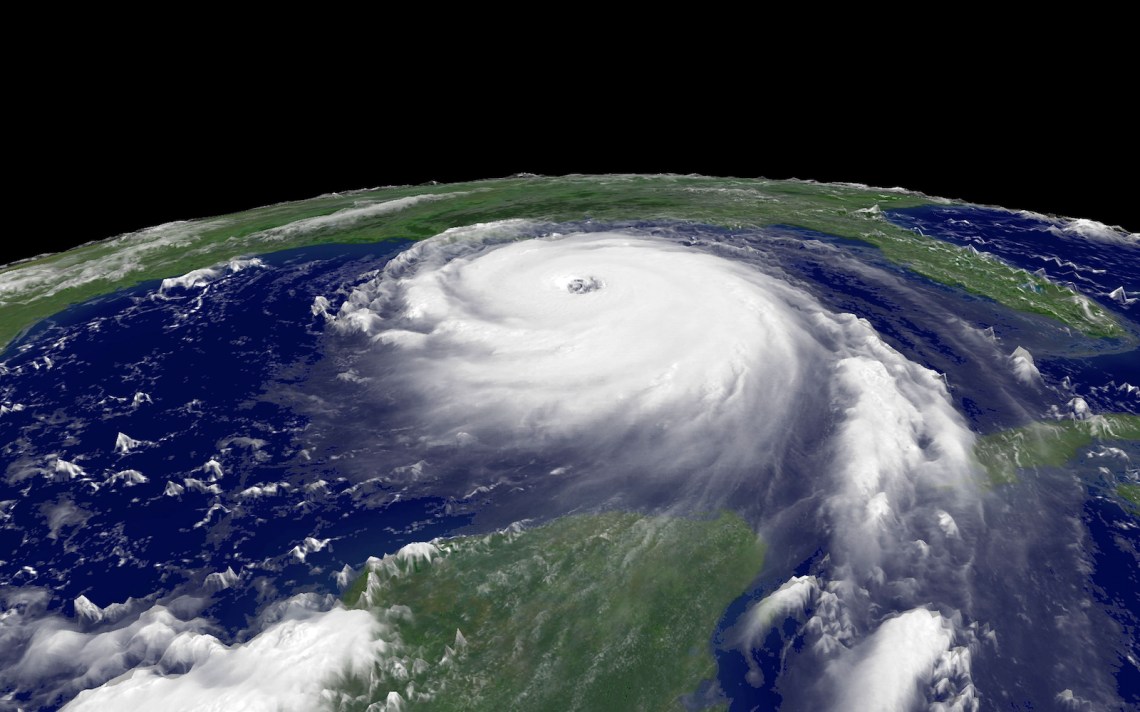

A superhuman character demands a superhuman setting and timeline. Storm begins, and ends, with a cosmic view of earth—as seen from outer space. The same image of the earth, adrift in blackness, would first appear in a photograph taken by the crew of Apollo 8 in 1968, a symbol that would launch the modern environmental movement. Stewart, uncommon among novelists who, as he would later complain, “want to emphasize the connection of people all the time,” defiantly takes the global perspective. He traces the narrative of his heroine back to the history of the glaciers that forged Donner Pass, the influence of the sun’s passage on the trade winds, and the effect of the earth’s rotation on polar air. “If the earth had not been revolving,” writes Stewart,

the frigid air might merely have moved out in all directions from the pole, pushing beneath the warmer air in somewhat orderly fashion, as ink spilled upon a blotter seeps out to form an ever larger circle. But actually the cordon of storms surrounded the polar air, holding it back by the force of their winds as a line of police, now jostled back a little, now pushing forward, restrains an angry crowd.

As far as Maria’s concerned, her only peers are the mountains and rivers she bestrides, the trade winds she navigates, and the atmosphere of which, for a brief reign, she is queen.

While Stewart endows Maria with limbs, intelligence, and a personality, his human characters, some of whom only appear once or twice, are as faceless, anonymous, and freethinking as the ants they resemble when seen from the troposphere. Most are nameless, denoted only by professional title: the Navigator, the Secretary of the Trade Association, the Chief Service Officer. The most prominent of the secondary characters, perhaps to neutralize their sustained presence in the novel, are further anonymized to abbreviations, the already lowly Junior Meteorologist reduced to the J.M., the humble Load-Dispatcher to the L.D. Confronted with the storm’s cunning, Stewart’s men and women respond with either blind self-interest or the brainlessness of deer. When the Road Superintendent inspects snow-buried traffic, he encounters “one pair of eyes after another staring out stupidly, looking a little perturbed but just waiting for somebody else to straighten things out.” As an epitaph for our species, it’s hard to improve. “By God, by God, but civilians were a poor lot of mammals,” thinks the Flood Control Co-ordinator. “It might be a good thing,” he concludes, “if the whole valley (or the whole world perhaps) should become only a far-stretching welter of brown waters with a few heads bobbing about here and there for a little while.” Those final four words are especially good, a gratuitous sadistic twist.

As Stewart elevates the storm to protagonist, and demotes his human beings to animal passivity, what seems at first a high-concept premise develops into something more radical. Stewart’s biographer, Donald M. Scott, calls Storm “the first ecological novel,” which is fair. The term “ecology” was coined in 1866 by the German zoologist Ernst Haeckel to describe the study of the relationships between living organisms—including human beings—and their environment. Storm’s drama hangs on the influence of environmental conditions on human fate, on the revelation of indirect but profound connections between erosion, ice melt, and vermicular digestion on the intimate lives of Americans who give no thought to the natural world beyond the daily forecast. Though they don’t tend to realize it, they are as beholden to the world’s biological cycles as are trees or sow bugs.

Stewart’s prose is never more rhapsodic than when he charts profound transformations that unfold over vast, inhuman stretches of time: the beaver colony’s work to impede the flow of a mountain creek, rainwater’s patient assault on limestone canyons, a river’s magic trick of turning a mountain into a molehill. In his spriteful dramatizations of natural processes, we see Stewart for the kind of writer he really is. He is not chiefly concerned with writing novels about complex human imbroglios, like The Petrified Forest or Grand Hotel, which he cited as initial models for Storm. He is instead a poet-ethicist in the tradition of John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Annie Dillard, a dramatist of the natural order and our fragile standing within it.

Advertisement

A major running subplot concerns the decomposition of a cedar tree that first sprouted on a ledge in the Sierra Nevada in 1579—a drama that reaches its culmination, more than a hundred pages and about three hundred and fifty years later, when the bole drops down a cliff and snaps a telephone pole. Stewart follows the ecological ramifications past the mountain range and into society. The collapse of the cedar leads a Boise man to lose a prospective job, denies a girl in Omaha a final conversation with her dying mother, and ensures a divorce in Reno. Such chains of events recur frequently throughout the novel—falling air pressure in Winnipeg causes a storeowner in Sacramento to buy a new car; heavy rain over central California brings suicides in Florida. The desperate actions of human beings in response to the storm come to seem as predictable as the stages of the hydrologic cycle or the circulation of the oceans. As the reader stands back, counseled by Stewart to take the galactic view, it becomes clear that the panics and euphoria caused by Maria are not the exceptions but the rule. Maria, after all, is not a particularly severe storm. It is not even unusual. As Stewart writes, “Other storms would come.”

After Storm, Stewart would write a quartet of ecological novels, all inventive in form and all but one of them best-sellers. The most prominent of these is Earth Abides, which has never gone out of print, the parable of an ecologist who survives a plague that has killed most of humanity. It would be a full generation, however, before other novelists tried to apply ecological thinking to their fiction—a gap in the literary record that we can see plainly from the distance of several decades, as a paleoclimatologist can detect a drought in the varying widths of tree rings. “Most people are not interested in the natural background,” Stewart would say near the end of his life, “at least not most novelists.” It would be two generations before any novelist dared again to attempt that most ineffable and maddening of subgenres: the climate novel.

In The Life and Truth of George R. Stewart, Scott notes that a little more than a year after Stewart’s death, in 1980, a “century-sized Maria of a storm hit California.” San Francisco received half of its annual rainfall in a day; eighteen thousand landslides occurred in a night. At Thornton State Beach, a small park just south of San Francisco that Stewart had frequented, an avalanche of mud buried the George R. Stewart Nature Trail. Maria, or one of her great-granddaughters, had paid him a tribute.

That storm, in the final analysis, was not unusual either. What was unusual was the existence of the state park, the product of shortsightedness and unmerited optimism in the powers of human enterprise: it lay on a vulnerable hillside below Route 35, dangerously exposed to the action of tides and coastal storms. Four decades later, the park remains closed to the general public.