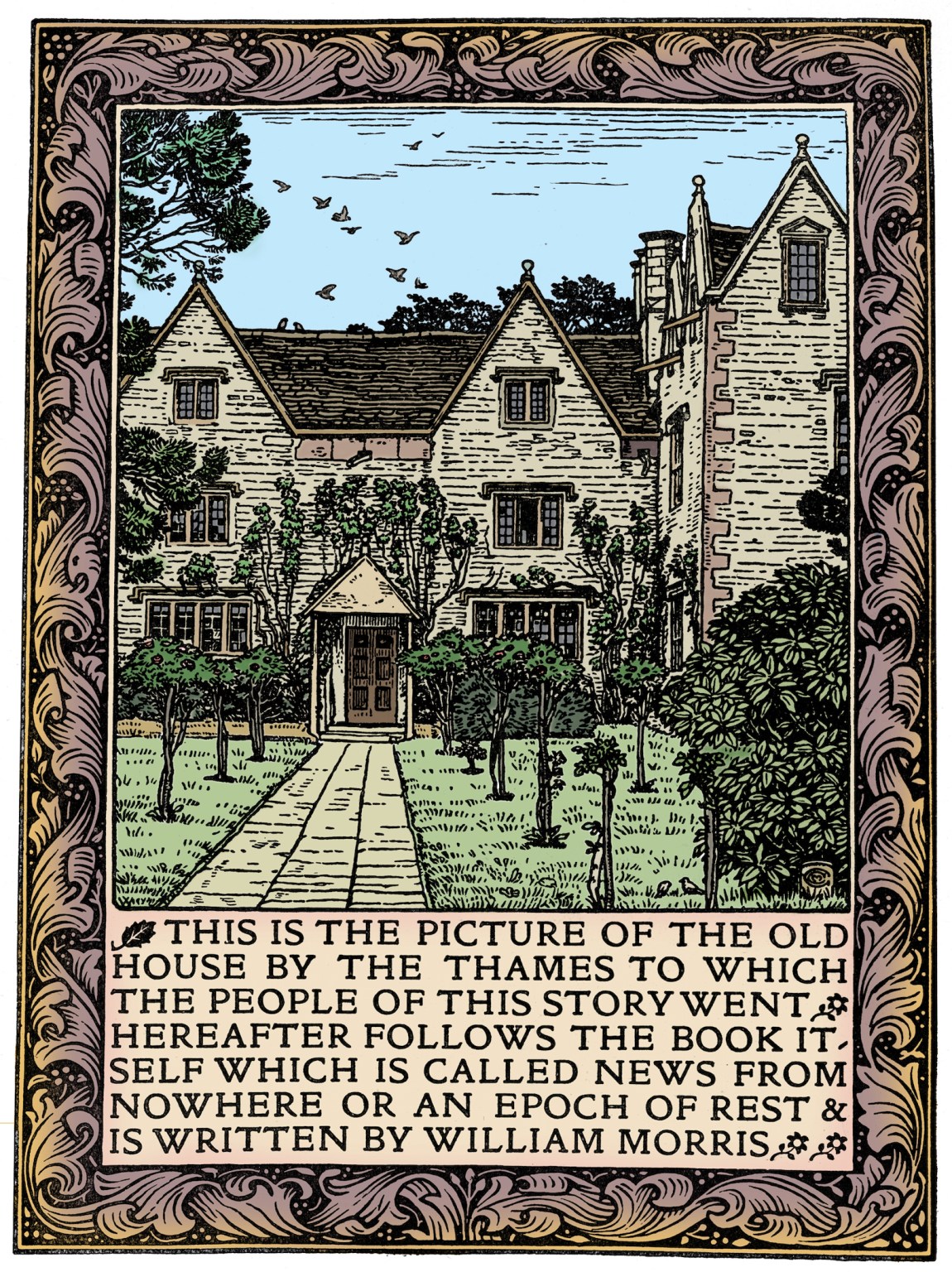

At the end of William Morris’s News from Nowhere, or, An Epoch of Rest (Being Some Chapters from a Utopian Romance), a woman named Ellen explains to the visitor, William Guest, that he cannot stay in this perfect place of clean air, meaningful work, and satisfying leisure. Not because of any fictional science of time travel, nor because he poses a threat to this particular future’s social harmony, but because his very being has been so thoroughly deformed by the social conditions of nineteenth-century industrial capitalism that he is incapable of experiencing the pleasures and desires of a world freed of competition, exploitation, and suffering. “You belong,” explains Ellen, “so entirely to the unhappiness of the past that our happiness even would weary you.”

In 1890, the year News from Nowhere was published, twenty-four-hour deliveries, video calls, and space travel were fictional. The environmental destruction produced by diesel-fueled trucks, rare earth mining, and rocket fuel were also in the future. But our own unhappiness remains strikingly similar to what Morris had in mind. It is a misery particular to global capitalism. Or rather, it is a constellation of miseries, unevenly distributed, like everything else, that results from the gross exploitation of nature and people necessary for supplying profitably our pleasures and comforts.

Many aspects of News from Nowhere set it apart from other utopian fiction of the time—it is decidedly socialist, conscious of the environmental costs of industrialization, backward-looking rather than futuristic, and free of prescriptiveness about any particular social arrangements—but Ellen’s melancholy observation on the psychic life of the capitalist subject is singularly important. If no other argument for revolutionary change made within the novel seems persuasive, this line, appearing late in the narrative, should give us reason to consider the insufficiency, even the costs, of a pragmatic reformist mindset. At a moment in history when social reform and conservationist policy have appeared on the political horizon, William Morris offers a reminder of the constitutive limits of our imaginations. He urges us to wish harder, not plan better.

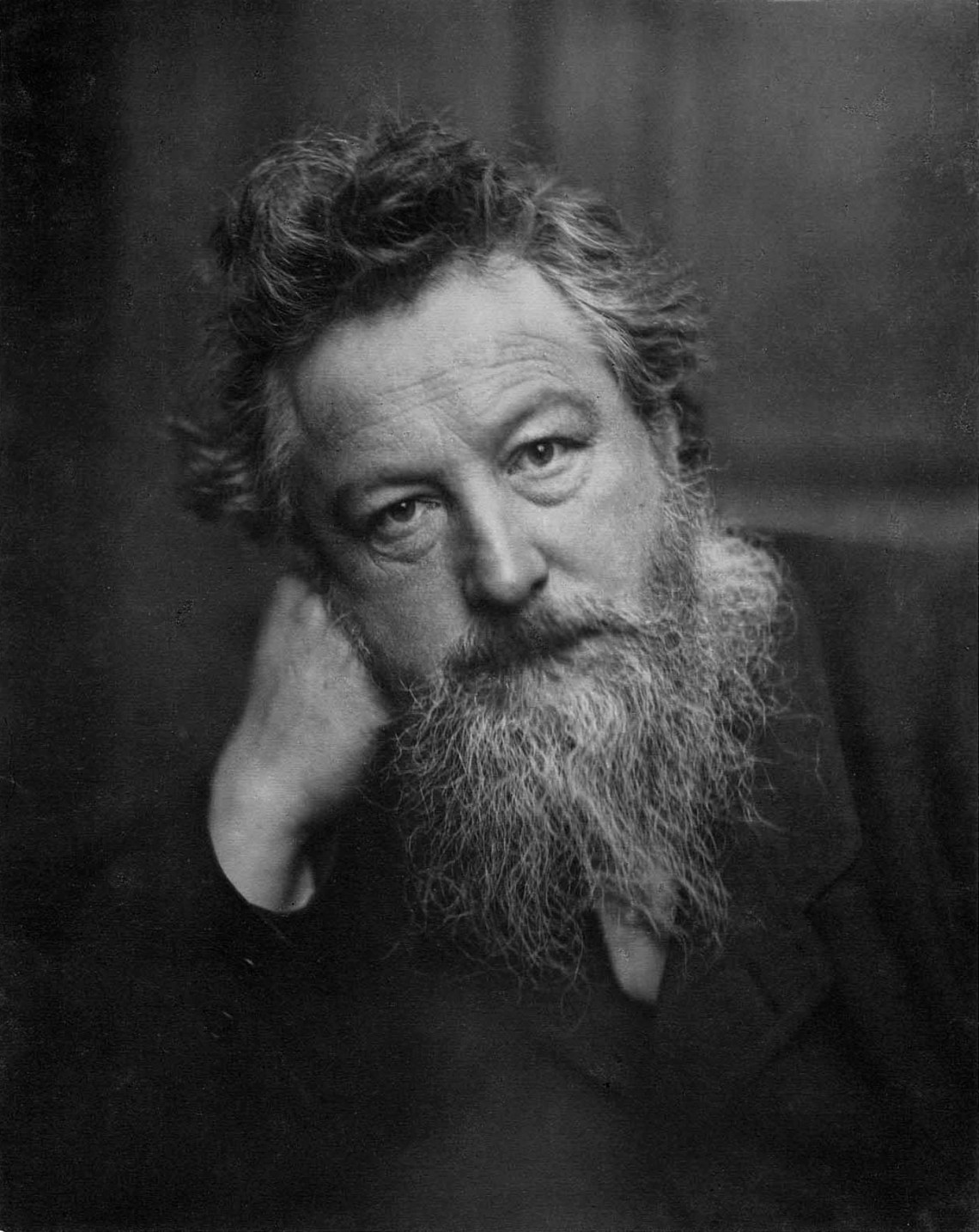

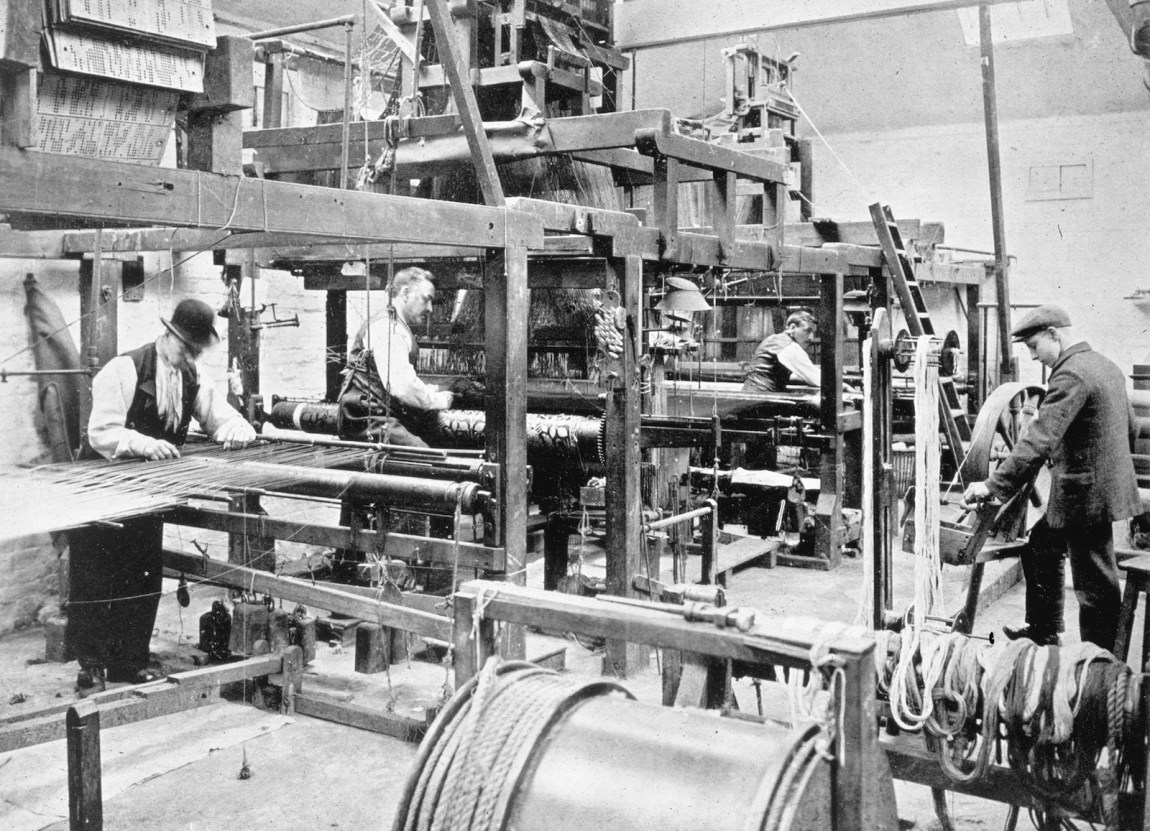

Morris was born in Walthamstow, Essex, northeast of London, in 1834. His influence on the decorative arts cannot be overstated. He was a founding member of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris’s firm produced high-end textiles, stained glass, and furniture, and his wallpaper designs, in particular, are familiar to many who might not even know their author. Morris’s quaint dictate, quoted ad nauseam, “Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful,” is not inconsistent with his worldview. He was concerned with beauty and utility, and horrified by the shoddy, mass-produced goods cranked out by industrial capitalism.

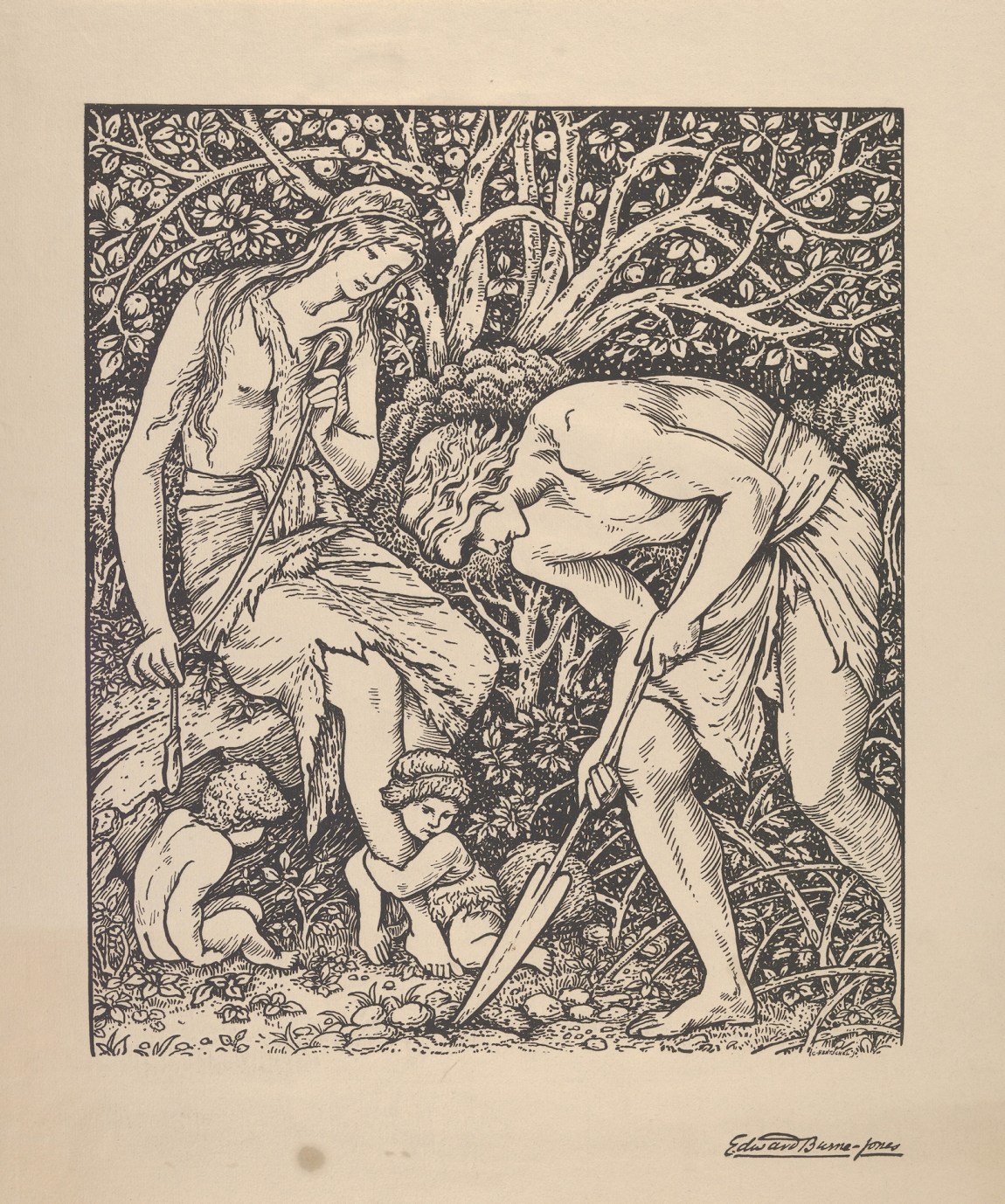

In common with the Pre-Raphaelite group of artists, with whom he associated, Morris took an interest in all things medieval. In his case, it was a predilection for the precapitalist past acquired while studying classics at Oxford, and one he maintained for the remainder of his life. But Morris did not think that wallpaper and well-lit factories were sufficient remedies for the ills of industrial society. Decoration was important—without it, “our rest would be vacant and uninteresting, our labor mere endurance, mere wearing of body and mind”—but to imagine that decoration alone would make work interesting and leisure fulfilling was a category error, a fundamental misrecognition.

There are plenty of people with a taste for art, Morris wrote, especially among the cultivated classes, but the self-congratulation of those who produce high art, appreciate so-called beauty, and imagine well-appointed rooms to be evidence of advanced civilization “do not know what the scope of art really is, and how closely it is bound up with the general condition of society.” Art, he argued, is not “founded on the special education or refinement of a limited body or class.” It is, rather, “man’s expression of his joy in labor.” And given that the majority of men labored without pleasure, indeed with a fair amount of pain and misery, there couldn’t possibly be much beauty in the world.

According to his biographer, the British historian E. P. Thompson, Morris was the immediate heir to the Romantic revolt against the Enlightenment rationalism that had, with the first industrial revolution, congealed into an oppressive, mechanistic instrumentality. But unlike conservatives such as Thomas Carlyle, who was as horrified as any reformer or radical by the reduction of social relations to a matter of exchange, Morris’s conversion to socialism transformed his aesthetic and cultural concerns into a rich source of a critique of society with enduring explanatory power. Where Carlyle saw a malady, Morris saw symptoms of some more systemic pathology. In the formulation of the French political philosopher Miguel Abensour, Morris invented “a juncture between romantic rebellion and the new revolutionary demand.” The fullest expression of this was News from Nowhere.

Advertisement

The secular humanism of the Renaissance, Martin Luther’s revolt against church authority, and the economic and intellectual shifts brought about by imperial expansion and mercantile trade networks made speculations about social perfection and distant societies a concept in need of a name. In 1516, Sir Thomas More coined the term “utopia” for just such a purpose. It means, literally, “no place.” More’s Utopia begins with an alphabet and lays further claim to reality with a character’s derisive verse announcing the superiority of Utopia to Plato’s Republic, which “was just a myth in prose.”

More’s is, like all literary utopias, a profoundly political work, but it is not necessarily prescriptive. In his case, fiction was a life-preserving hedge, and what he intended to lampoon rather than promote is endlessly debatable. As a deeply religious person, he would have held a worldview fundamentally incompatible with the notion that men could plan perfection on Earth. On the other hand, the monasteries of More’s faith might reasonably be cited as early instances of ideal communities planned for harmonious living. In any case, his original Noplace set certain precedents, of both conceit and content, that are important for considering utopia’s uses.

Foremost among those, of course, is Utopia’s function as an elaborate instantiation of an imagined political situation that is, by all appearances, wildly unrealistic in the terms set by the society inhabited by the author (or narrator). This lack of realism is organically absorbed by utopia as a genre of fiction, but in spite of its being one of the more contrived literary forms, utopia has never been successfully contained by the organizing dichotomy of fantasy and reality. In popular speech, “utopian” has come to designate not complete fiction but, rather, outsized expectations for change. Conversely, as fiction, utopia is often read as a programmatic recommendation—in a way that literary realism never would be. Despite a quasi-theological insistence by certain factions of the political left on a cleft between utopianism and other forms of radical politics, utopia in common usage is all but defined by its connotation of the absurdly unrealistic idealism of all hopes for a revolutionary transformation of social relations. And indeed, utopian fiction tends to be heavy on planning and bogged in technical detail, and suffers, according to the Marxist geographer David Harvey, from either totalitarian impulses or an endless proceduralism.

The early nineteenth century saw another utopian moment that can be linked to major social upheavals, this time in the form of the French and American Revolutions. Major thinkers included Charles Fourier and Henri de Saint-Simon in France and Robert Owen in England. All three made serious proposals for planned communities organized around common property. This did not necessarily make them socialist, or even egalitarian. Fourier’s phalansteries, for example, made their premise for successful communal living a strict observance of class and other demographic distinctions. Saint-Simon was more dedicated to egalitarianism but was also deeply religious, and his social schemes were predicated on something closer to Christian notions of brotherly love than socialist principles. Still, Friedrich Engels cites all three as important, if flawed, early socialist thinkers.

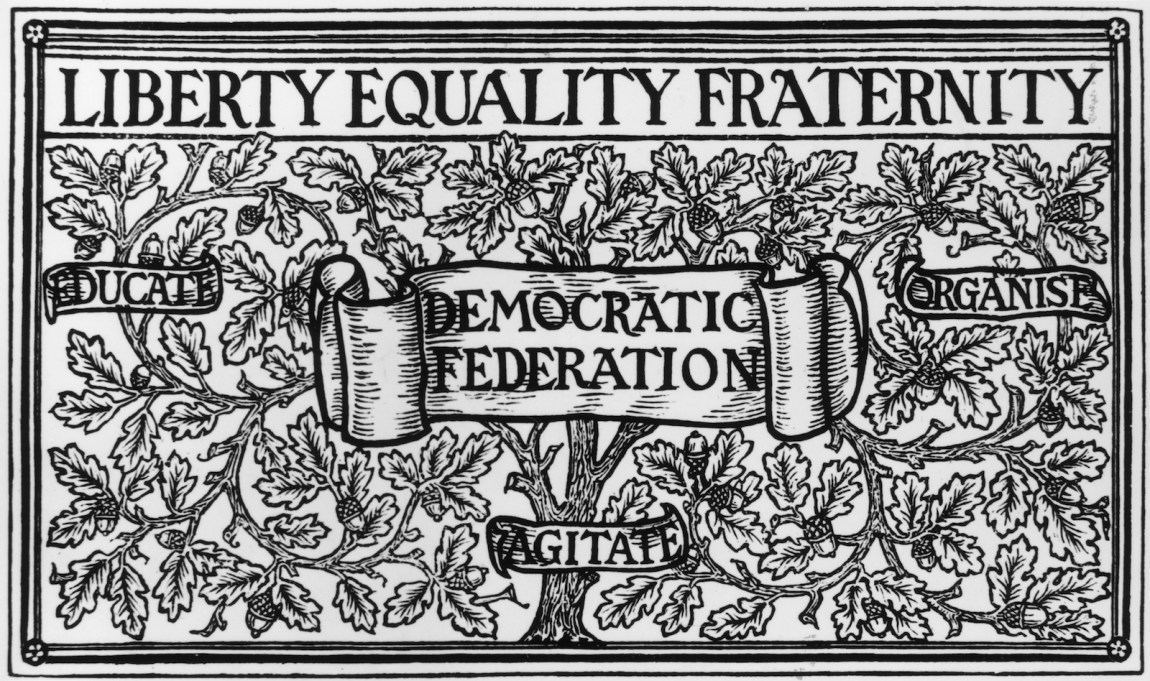

In 1882, Morris was introduced to socialism, and the following year he joined the Democratic Federation. He threw himself into organizing, founding the Socialist League in 1885, as well as its official publication Commonweal. In addition to serving as editor and being one of the main contributors to Commonweal, Morris went on the lecture circuit, giving talks such as “Art under Plutocracy” and “Useful Work versus Useless Toil.” He read Karl Marx’s Capital in French (he “suffered agonies of confusion of the brain over reading the pure economics of that great work”) maintained respectful relations with Friedrich Engels (who “regarded Morris’s medievalism ‘with good-humored toleration’” and associated himself with the Socialist League by contributing to Commonweal), and generally immersed himself in the newly vibrant socialism of 1880s London.

Utopia had continued to be a common fictional device throughout that century. One of the most influential of these literary productions was Looking Backward (1888) by the American Edward Bellamy. William Morris, unlike almost every other contemporary reviewer, hated this “very watery tincture of socialism.” Bellamy’s early novelization of what would become the socially responsible, egalitarian, and technocratic political core of American progressive politics was, according to Morris’s critique, the reflection of an “unhistoric and unartistic” personality whose imagination ends at the industrious, professional middle class. The novel’s so-called socialism came about gradually and, ultimately, as a result of consensus’s forming around the irrationality of capitalist distribution. There was, therefore, “no breakdown of that life, or indeed disturbance of it.” Bellamy eschewed any frightening language of change and conflict, but then his characters gained nothing but the right to work a little less and consume a little more in a landscape that was essentially a cleaned-up version of the one they already knew.

Advertisement

This wishful narrative of a mass coming-to-sense is all too familiar in mainstream liberal thought. Morris would have none of it. When he wrote his full response, in the form of his answering fiction, News from Nowhere, he made sure to include, as the backdrop to his story, a preceding great and bloody upheaval. Only the oldest of citizens had any memory of it or even any desire to know what had happened. In a society that was free of conflict, the discipline of history no longer served any function. But the war to end all wars had been a war—it was not a smooth transition brought about by the superior reasoning of reformers.

It was not, however, Morris’s Commonweal comrades but John Ruskin who first gave him “a form for his discontent.” In particular, it was Ruskin’s essay “The Nature of the Gothic” that inoculated Morris’s thinking against the pseudo-socialist reform mentality exemplified by Bellamy. Art is nothing less, Ruskin suggested, than an expression of social conditions in their entirety. This is different from claiming that certain styles are suitable to, or expressive of, a particular political tendency. His claim is much grander if highly subjective: in a world saturated with shoddy, factory-made objects that embody the misery of their own production, Gothic architecture represented a rare instance of actually existing beauty.

Ruskin crystalized the deficiencies and disappointments that organized the psychic life of a youthful Morris into a positive argument about a loss of pleasure in work. In Gothic workmanship, Ruskin argues, is “perpetual change,” indicating that the laborer or artisan must have been not only unburdened by his work but “altogether set free” by performing it.

If Morris’s political writing can be said to have a unifying quality, it is certainly the centrality of pleasure. Or more precisely, the ways that work, beauty, and pleasure have been deformed under capitalism and how they may be recovered. The more typical, reformist sensibilities in Bellamy’s work—superficially egalitarian, comfortably rational, and acceptably middle-class—should have been appealing to someone in Morris’s position and, indeed, in isolation, many of Morris’s statements about commodious living arrangements would fit comfortably in the mouths of Bellamy’s future citizens. But what was lacking in Bellamy was any real disjunction, any sense of a radical difference between then and now; what Ruskin’s writing did was to provide, in its fashion, proof that such difference was possible, that vague, abstract-seeming concepts such as beauty would be fundamentally altered by new productive relations in a reordered society.

Such actually existing beauty is, like the protagonist Guest in Nowhere, an alien presence, and any language that came readily to mind would prove inadequate to the task of describing something as radically unfamiliar as the Gothic. Or, more accurately perhaps, the Gothic might be described but not defined. It escapes the nineteenth-century mania for industrial patterns, figures, and all that is measurable. What it emphatically does not give us is uniformity, which is, according to Ruskin, architectural evidence of terrible working conditions: “wherever the workman is utterly enslaved, the parts of the building must of course be absolutely like each other.” Whereas, for Ruskin, the Gothic is aesthetic evidence of a better life made solid and material, if always elusive and forever escaping definition:

We have, then, the Gothic character submitted to our analysis, just as a rough mineral is submitted to that of the chemist, entangled with many other foreign substances, itself perhaps in no place pure, or ever to be obtained or seen in purity for more than an instant.

Morris inherits not just the content of these arguments but the conviction—the “of course” of Ruskin’s architectural pronouncements—that a building or any other object should be “[read] as we would read Milton or Dante.” Or, more to Morris’s taste, as he would read Romantic poets, Icelandic sagas, and medieval romances.

In 1884, William Morris, addressed the Hammersmith Branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF). “Revolution,” Morris began, “has a terrible sound in most people’s ears.” Even though revolution is not necessarily synonymous with “riot and all kinds of violence” and refers only to “a change in the basis of society, people are scared at the idea of such a vast change and beg that you will speak of reform and not revolution.” But reform was not what Morris was after, and the polite “envelope” provided by the word only disguised a situation that was “no less dangerous for being ignored.” Revolution and utopia both involve terrific imaginative leaps.

The former might seem more realistic because it is implicitly embedded in historical events. On the contrary, the imaginative exercise that is utopia, as well as Morris’s lifelong dedication to what society had deemed, in his words, the “lesser arts” and to things beautiful and, seemingly, politically insignificant, should remind us of the normative character of pronouncements about political realism and social significance, and how we conventionally define failure and success. From class division down to the separation of high art from mere decoration, capitalism has, according to Morris, thoroughly perverted our relations to the world. And this is why a selective return to precapitalist modes of production and social organization can be an imaginative asset for a utopian writer and revolutionary thinker. Future projections based on current modes of production are constrained by a logic of progress that is itself an invention of industrial capitalism.

News from Nowhere is not an accidental product of Morris’s youthful enthusiasm for Arthurian romance but a unique contribution to a genre that was, even then, in the process of being overtaken by science fiction—that is, fantasy based on capitalism’s promise of constant technological advance. And Morris’s fiction thus depends upon the revolutionary moment, a rupture in the mechanical, productive continuum of industrial progress. Morris’s “no place” proposes a world so different looking that even the institutions we consider salutary disappear. In fact, almost every activity that once filled our time is eliminated through an organic process of attrition following that radical break.

Revolution is frightening and utopia is boring. Fear and boredom, affectively different as they may be, both issue from a strong aversion to fundamental social change. Frederic Jameson has suggested that rather than being afraid of the bloody revolution necessary for the achievement of a radically reorganized, perfect society, we are, in fact, afraid of utopia itself: the end, rather than the means. To say that we would be bored by utopia—that, in the words of Morris’s character Ellen, “happiness even would weary [us]”—is not a minor observation. Consider for a moment what would we do without suffering, without competition, without conflict. This is the stuff of professional motivation, of satisfaction in accomplishment, of romantic triumph. It is both how we live and how we entertain ourselves.

Utopia, as both way of life and literary genre, can therefore seem bland to the point of being soporific. As important for Jameson, though, is the “statistical” quality of the citizens of utopia:

This effect of anonymity and of depersonalization is a very fundamental part of what utopia is and how it functions. The boredom or dryness that has been attributed to the utopian text…is thus not a literary drawback nor a serious setback, but a very central strength of the utopian process in general.

This is, after all, what radical egalitarianism implies: in Jameson’s words again, a “desubjectification” that signifies the “loss of psychic privileges and spiritual private property, the reduction of all of us to that psychic gap or lack in which we all as subjects consist, but that we all expend a good deal of energy on trying to conceal from ourselves.”

Morris was acutely aware of this fear that, logically enough, grows in direct proportion to material comfort. The beneficiaries of capitalism have more to lose materially speaking, but more importantly, these comforts correspond to and reinforce “psychic privileges and spiritual private property”—the very ability to conceive of oneself as an individual who strives, accomplishes, creates, and exists as a singular and independent entity. Morris’s writings on revolution, work, and pleasure were not solely intended for middle-class readers, yet this is the audience he often ended up addressing, and it was, he knew, the class position most familiar to him. How to sell revolution to those who had abundance, not “nothing to lose but their chains,” was a matter that required more than enlisting their sympathies in the form of donations and letters to their members of Parliament. Converting this class to the cause of socialism meant persuading them that revolution was desirable and that their self-annihilation as a class would be an improvement.

“I must ask the rich and well-to-do what sort of position it is which they are so anxious to preserve at any cost,” he asked. If they would give an honest answer to this, he argued, it would have to be their place atop a vast scheme of militarized imperial plunder. “Our present system of society,” he told his largely genteel Hammersmith audience, “is based on a state of perpetual war.”

Capitalism depends on both exploitation and expropriation. These two forms of wealth production tend, in our time, to map onto a core–periphery model of society that allows those of us inhabiting the metropole to imagine that affordable healthcare, living wages, or a universal basic income are capable of solving every social ill. Such reforms, if realized at scale, would indeed improve the lives of many, and that, given the current state of affairs, seems as radical and even utopian as anything available. But even if we managed to do away with the worst forms of wage-labor exploitation, its “better” forms would inevitably involve continued extractive profiteering and rent-seeking from somewhere else.

Morris’s utopia offers us a glimpse of how we might live without the never-quite-suppressible knowledge that pleasure under capitalism is always—no matter how local and green and clean and responsible you are—implicated in another’s suffering. The very comforts and conveniences we take for granted are supplied by that state of “perpetual war,” with all the death and destruction that entails. This sounds melodramatic, perhaps, and the solution sounds impossible, but the thought experiment is worth entertaining. Utopian modes of thought are, in fact, habitual to us: capitalism itself excels at futurology, and what is the popular liberal conviction that an invisible hand might equitably distribute goods and services if not completely utopian? The world we inhabit is full of elite planned communities and extravagant, cargo-cultish infrastructure projects promising economic prosperity to anyone in their orbits.

Revolution is frightening and utopia is boring. But if we could contemplate exchanging our present perpetual war for an unknown future, and a perhaps painful confrontation with the way that our very desire, our quest for fulfillment, is shaped by a system that necessitates exploitation, we might, like the narrator in News from Nowhere, experience unalloyed pleasure:

Here, I could enjoy everything without an after-thought of the injustice and miserable toil which made my leisure; the ignorance and dullness of life that which went to make my keen appreciation of history; the tyranny and the struggle full of fear and mishap which went to make my romance.