“I could spend my life prying loose the secrets of the insane,” André Breton wrote in the founding document of his new art movement, Surrealism, in 1924. “These people are honest to a fault, and their naiveté has no peer but my own. Christopher Columbus should have set out to discover America with a boatload of madmen.”

Breton’s reverence for insanity was far from unusual in avant-garde circles after World War I. Modernism had only recently sprung from the massive social change caused by the late-nineteenth-century technology boom. All the assumptions of the old, agrarian world—that God existed, and humans lived in tight-knit rural communities, surrounded by nature—no longer held when people moved to overcrowded cities to work in the new, industrialized societies. In the modern era, the art that had been taught for so long in the academies, with its classical subject matter and its strict ideas of proportion and beauty, was irrelevant. Instead, the alienated urbanites turned inward, searching for inspiration in sources they believed were untainted by bourgeois values and “civilization,” including the art of so-called “primitives,” of children, and the insane.

Then came the war. The carnage brought trauma to almost every household in Europe, and artists suffered as much as everyone else. Two of the leading lights of German Expressionism, Franz Marc and August Macke, were killed in the fighting. The sculptor Käthe Kollwitz lost her eighteen-year-old son, Peter, in Belgium: she would pour her grief into her work for the rest of her life. Many of those who survived the combat suffered nervous breakdowns, as Max Beckmann, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and George Grosz did. Others, such as Otto Dix, would spend years afterward reproducing the visions of deranged, grinning soldiers and gas mask–wearing aliens that had been seared into their minds at the front.

In 1916, a group of artists sheltering in Zurich, Switzerland, launched a deliberately irrational response: Dada. “Repelled by the slaughterhouses of the world war,” the movement’s Jean Arp explained, “we turned to art…. We searched for an elementary art that would, we thought, save mankind from the furious madness of these times.” By the war’s end, insanity had become a central theme for art. On top of its pre-1914 significance, madness was now an emblem of resistance to the generation of warmongers who had been so reckless of human life.

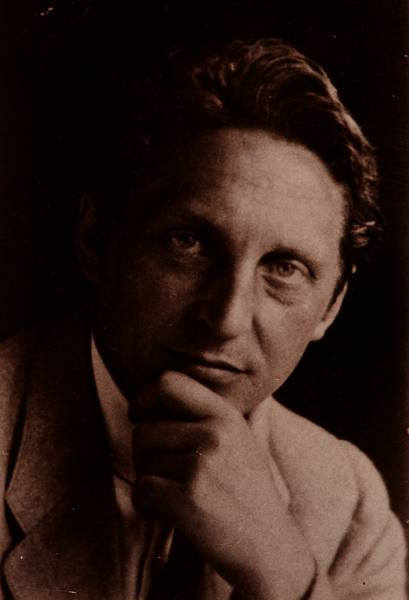

It was onto this terrain that a young assistant psychiatrist, Hans Prinzhorn, stepped at the start of 1919. Recently demobilized, Prinzhorn arrived at the prestigious Heidelberg University Psychiatric Clinic with a specific, self-defined role: he would gather a great quantity of the creative output of psychiatric patients. He was unusually equipped for this task, having trained both as an art historian and as a medical doctor. He also had his own psychological problems, possibly the result of his wartime experience. During two years of obsessive letter-writing, traveling, and collecting, he compiled what would become the most famous assemblage of psychiatric art in the world. It included thousands of works of every kind—sculpture, drawing, needlework, writing—executed with whatever came to his artist-patients’ hands, from chewed bread to discarded nursing rotas, even toilet paper. All had been created by residents of psychiatric institutions, and most were diagnosed with schizophrenia—a term recently coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler.

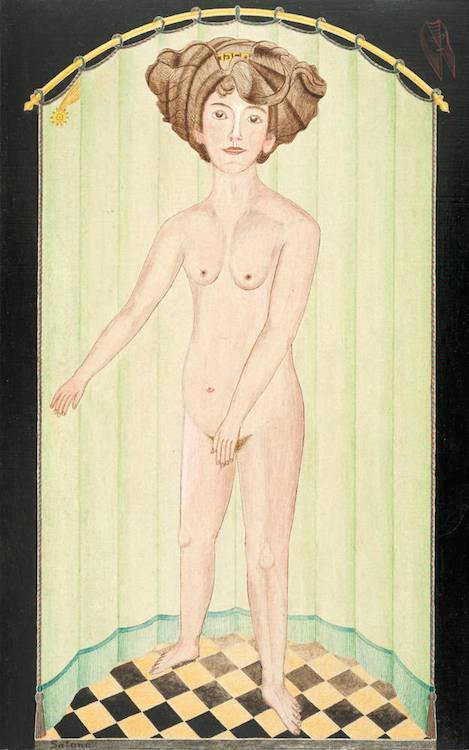

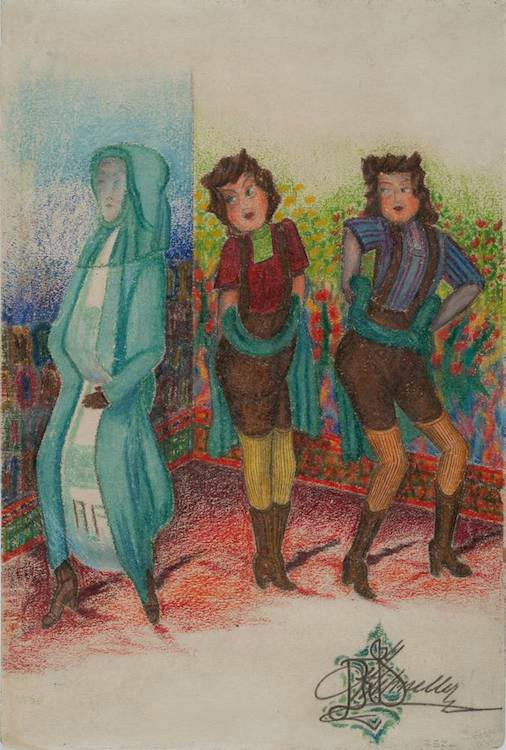

The Heidelberg Clinic hoped the collection would help with diagnosis, but Prinzhorn soon took against this idea: psychiatry had no business judging people by their creations. Instead, he was astonished by its value as art. He encouraged some of his favorite patients to produce more by offering small gifts of money or tobacco. In 1922, he published the conclusions of his study, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken, or Artistry of the Mentally Ill, a lavishly illustrated volume in which he identified ten of his greatest finds, his “schizophrenic masters.” Prinzhorn sketched out a medical biography of each “master,” alongside their work, though he used pseudonyms to protect their families from the stigma of mental illness.

To promote his findings, Prinzhorn took to carrying a portfolio of patient art wherever he went, and it left a profound impression on everyone who saw it. It seemed to force people to confront fundamental questions about schizophrenia and the zeitgeist, he observed. The artistic avant-garde’s response was dramatic. Professional artists who saw the images fell into a handful of distinct groups. There were those who admired or dismissed the pictures without differentiating “healthy” from “sick” work, and then there were those who renounced it all as “non-art” but who were fascinated nevertheless. A third category was “shaken to their foundations” by the material, Prinzhorn wrote, and believed they had discovered “the original process of all configuration, pure inspiration, for which…after all, every artist thirsts.”

Some were so overwhelmed that they were forced to reconsider their entire oeuvres. One such artist was Oskar Schlemmer. Schlemmer was at a crossroads in his artistic development in the summer of 1921, when he saw the Heidelberg works at one of Prinzhorn’s lectures. The experience sent him into a rapture. “For a whole day I imagined I was going to go mad,” he wrote to his fiancée, Helena Tutein, “and was even pleased at the thought, because then I would have everything I have been wanting; I would exist totally in a world of ideas, of introspection—what the mystics seek.”

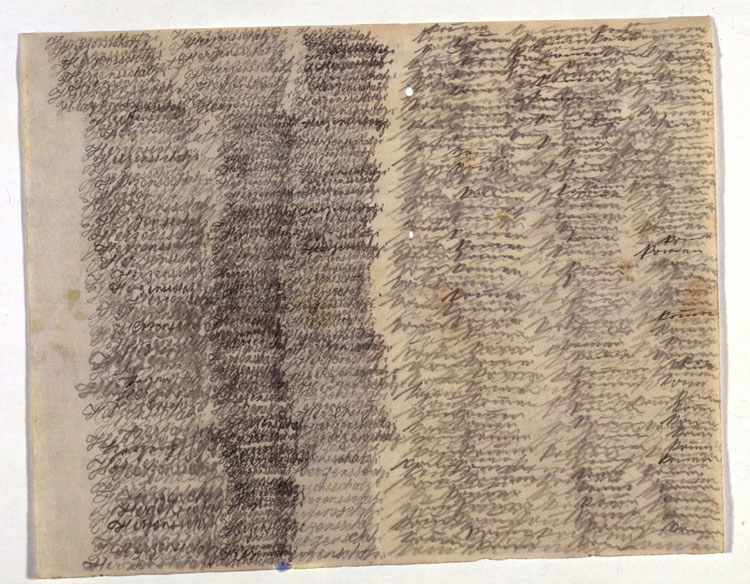

Schlemmer was particularly fascinated by the Prinzhorn artist Baron Hyazinth von Wieser, a law graduate from Vienna who believed his life was governed by magic and supernatural forces. The baron had invented an abstract system of “-ologies”—including willology, ideology, sexology, and jokeology—in which human characteristics were translated into geometric shapes. He had drawn a sheet of delicate symbols representing several of these states and had written across the top of this chart: “Dangerous to Look At!” Schlemmer couldn’t get this idea out of his head.

Of course, Schlemmer told Tutein, Prinzhorn’s material would be used as an indictment of modern art—“See, they paint just like the insane!”—and he had to admit it was “a dangerous game” modern artists were playing by exploring mental illness. Even so, he envied the patients, since he believed “the madman lives in the realm of ideas which the sane artist tries to reach; for the madman it is purer, because completely separate from external reality.”

Artistry of the Mentally Ill became part of the cultural conversation in Weimar Germany. The volume was passed around the Bauhaus, where Paul Klee taught. “Look at these religious paintings,” Klee told a colleague, Lothar Schreyer. “There’s a depth and power of expression that I never achieve in religious subjects. Really sublime art. Direct spiritual vision.” Klee would borrow ideas and motifs from the book for his own work. Alfred Kubin, a veteran of the Munich Expressionist scene, found the material “stupendous” and “overwhelming,” and hurried to record his impressions with “a feeling of most uplifting joy.” He even exchanged some of his work with pieces from the Heidelberg collection, putting the “insane” art on a par with his own.

The greatest impact of Prinzhorn’s work, however, was felt not in Germany, but in Paris, the world capital of art. The book’s courier would be the Dadaist Max Ernst. In the summer of 1922, the Cologne-based artist emigrated to France, where he was to form a ménage à trois with the poet Paul Éluard and his wife, Gala. On arrival in the French capital, Ernst presented his new friends with a copy of Artistry of the Mentally Ill.

The gift enraptured Éluard. It was “the most beautiful book of images there is,” he wrote, “better than any painting.” Éluard was close to André Breton, and soon the lavish volume was being shared among the proto-Surrealist group. It came to occupy such a central position in Breton’s circle, in fact, that it would be routinely referred to as the “Surrealists’ bible.”

“All the Surrealists had [Prinzhorn’s] book on the art of the mentally ill in their hands,” the painter André Masson remembered of that time; it was the “revelation” that helped them to conquer the irrational and reject the values of classicism. Breton wrote that Prinzhorn had given the artist-patients a “presentation worthy of their talents” for the first time. In so doing, he had “called for a direct comparison of their work with that created by other contemporary artists, a comparison which in many respects turns to the disadvantage of the latter.”

The Prinzhorn artist most favored by the Surrealists was August Natterer, an electrical engineer from Upper Swabia in southern Germany. Under great professional duress, Natterer was standing outside a barracks in Stuttgart one day in April 1907 when he noticed a spot in a cloud. The spot appeared to slowly grow into a screen, sixty-five feet high, on which appeared a vision so vivid he would be able to recall it for the rest of his life:

On this board or screen or stage, pictures followed one another like lightning, maybe 10,000 in half an hour…[and] the Lord himself appeared, the witch who created the world—in between there were worldly scenes: war pictures, parts of the earth, monuments, battle scenes from the Wars of Liberation, palaces, marvelous palaces, in short the beauties of the whole world.

Ernst drew direct inspiration from Natterer. Obvious parallels can be seen between the patient’s Der Wunderhirte (the miracle shepherd) and Ernst’s 1931 collage Oedipus: both show sitting, free-floating figures, along with an animal, and emphasize the legs and feet. Natterer’s principles can also be found in a host of other Ernst creations, including his 1923 painting Der Sturz der Engel (the fall of the angel).

Advertisement

No Surrealist would go on to achieve greater notoriety than Salvador Dalí, who drew inspiration from at least two Prinzhorn artists, Carl Lange, a former salesman who saw miraculous figures in the sweat-stained insoles of his shoes, and a sadomasochistic former Bavarian railway employee named Joseph Schneller. It was said that Dalí spent most of the 1920s trying by every means possible to go insane, and when he failed, he developed his own insanity-emulation processes, including the “paranoiac-critical method.” Using this technique, he sought to bypass the brain’s systems for ordering the world by invoking a state of delusional paranoia, projecting his own interpretations onto objects around him, much as a child might spot a face or an animal in an oddly shaped cloud. The result was a series of visual double meanings that replicated insanity perfectly, Dalí claimed. “The only difference between myself and a madman,” he declared, “is that I am not mad.”

The Surrealists pushed their cult of insanity to absurd heights, romanticizing mental illness far beyond its often grim reality. Éluard pronounced that it was those outside the asylum who were imprisoned, and that liberty could only be found inside, while Antonin Artaud compared asylums to slave colonies and identified psychiatrists as a public enemy.

*

Not everyone liked what they saw in the Heidelberg collection, however. Prinzhorn noticed that the culturally conservative were the least enthusiastic about his material, and in 1921, a critic arrived at the clinic who exactly fit that description. Wilhelm Weygandt had recently become professor of psychiatry at the University of Hamburg. Though a political liberal, he was deeply reactionary when it came to medical and cultural issues. At a meeting of psychiatrists and neurologists in 1910, he had been so outraged to hear Freud’s ideas about child sexuality that he banged his fist on the table and yelled that it was a matter for the police. He had also put a great deal of effort into accumulating a gruesome collection of psychological artifacts, including almost three hundred skulls of psychiatric patients and a large quantity of case photographs of disabled people. He had his own patient-art collection, too: hundreds of examples of what he called “pathological art practice,” including drawings, paintings, sculptures, and embroidery.

Weygandt was at the forefront of a growing band of medical men who were alarmed at modern art’s preoccupation with insanity, and when he saw Prinzhorn’s work, he was livid. Soon after his visit, he poured his scorn into an article for the Berlin weekly Die Woche, in which he decried the obsession of “extreme modern art” with madness. The pictorial creations of the mentally ill could be “medically interesting,” he wrote, but there was no such thing as “mad art.” The alleged artistic expressions of mental patients were merely the clumsy, technically awkward “congenital nonsense” produced by insane impulses. Reproducing works from his own collection of patient art alongside those of professionals, he subjected artists to a disparaging psychiatric “analysis,” comparing a landscape by Klee with a “schizophrenic insane image” and conceptual work by Pablo Picasso with the “delusional ideas” of paranoid patients. He also described paintings by Paul Cézanne, Oskar Kokoschka, Wassily Kandinsky, Kurt Schwitters, and Vincent van Gogh in pathological terms. The amazing similarity between “mad art” and the “excrescences of modernism” was symptomatic of an Entartung, or “degeneracy,” an “aberration from the path of normal thought and feeling” which, “in our sick and troubled times,” contributed to lowering the dignity of mankind.

In raising the specter of degeneration, Weygandt introduced one of the canards of nineteenth-century thinking into the discussion around Prinzhorn’s material. As the French race theorist Count Joseph Arthur de Gobineau had defined degeneracy in the 1850s:

A nation is degenerate when the blood of its founders no longer flows in its veins, but has been gradually deteriorated by successive foreign admixtures; so that the nation, while retaining its original name, is no longer composed of the same elements.

By the 1920s, Gobineau’s ideas had spawned a host of cultural theories that attributed Western decline to contamination by alien elements—including the ideas of his friend, the composer Richard Wagner, who bemoaned Jewish influence on German culture in his essay “Das Judenthum in der Musik” (Judaism in music). It wasn’t long after Prinzhorn’s publication that unscrupulous politicians began using the connection between modern art and insanity for their own ends. Once Germany fell under the control of Adolf Hitler—himself a self-taught artist, and a war veteran diagnosed in 1923 as “a morbid psychopath…prone to hysteria”—his National Socialist regime used the pseudoscientific concept of “degeneracy” and the Prinzhorn collection as propaganda tools.

The “Degenerate Art” exhibitions that toured the Reich from 1937 would incorporate works from the Heidelberg collection to “prove,” as the official guidebook insisted, that modern artists were even more “sick” than genuine “lunatics.” At the conclusion of the “relentless war of destruction against the last elements of our cultural decomposition!” that Hitler announced in 1937, modern art in Germany had largely been eradicated, so-called degenerate artists forced into exile or banned from painting, and 200,000 psychiatric patients murdered in a “euthanasia” action that is widely acknowledged as a precursor to the Holocaust.

The Nazi destruction of people and paintings did not mark the end of art’s bonds with insanity, however, and Prinzhorn’s collection survived the war, most probably in case it was needed for a new propaganda show. After Hitler’s downfall, madness would re-exert its influence, thanks in large part to the French artist Jean Dubuffet.

Dubuffet had first encountered Artistry of the Mentally Ill as a young painter in the 1920s. “It showed me the way,” he said later, and made him realize that “all was permitted, all was possible.” At the end of World War II, he returned to Prinzhorn’s themes with a new movement, Art Brut, or “raw art,” which aimed to liberate art from the grip of the cultural establishment. He embarked on a journey of discovering, collecting, and publishing the work of psychiatric patients and other non-professionals. In September 1950, he traveled to Heidelberg to see Prinzhorn’s collection. Dubuffet spent two days at the clinic, taking copious notes. He would use the art of psychosis as inspiration for his own paintings of the human interior, which he described as “landscapes of the brain.”

Knowledge of the Prinzhorn artists once again began to spread among the European avant-garde, and in 1951 Dubuffet took his collection across the Atlantic, to New York, where it remained for a decade on the East Hampton estate of the Abstract Expressionist Alfonso Ossorio, a close friend of Jackson Pollock. Some of the most illustrious names in American art came to see Art Brut here, including Pollock and Lee Krasner, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, and the critics Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg. Dubuffet also traveled to Chicago, where he set out his antiestablishment agenda in a famous lecture to the city’s Arts Club. The theories he presented there sowed the seeds of another American art group, the Chicago Imagists.

In the 1970s, as collectors became more conscious of the many types of creative expression that existed beyond the artistic mainstream and the commercial art market, the British critic Roger Cardinal coined a new name for this kind of material: “outsider art.” A “revolution in awareness” had taken place, Cardinal proclaimed, in which galleries sought to address this immense field of overlooked activity, including psychiatric art, folk art, street art (including graffiti), and art by incarcerated people. From 1993, New York would host an annual Outsider Art Fair. Reporting from the twenty-seventh edition of the fair in 2019, The Art Newspaper asserted that commercial interest had made this diverse material a “hot commodity.”

The works Prinzhorn gathered can still be found at Heidelberg. His great achievement was to free them from the asylum and send them out into the wider world, where they both inspired modern artists and helped broaden the definition of what art could be. Since 2001, pieces from the collection have been displayed in their own gallery—something Prinzhorn always pushed for, but which never materialized in his lifetime—and, for some time now, researchers have been working to fill in the gaps in the artists’ biographies. For the most part, these talented individuals lived anonymous, stigmatized lives behind the walls of psychiatric institutions, through a terrible time in twentieth-century history. Now, at least, we know them by their real names.