This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

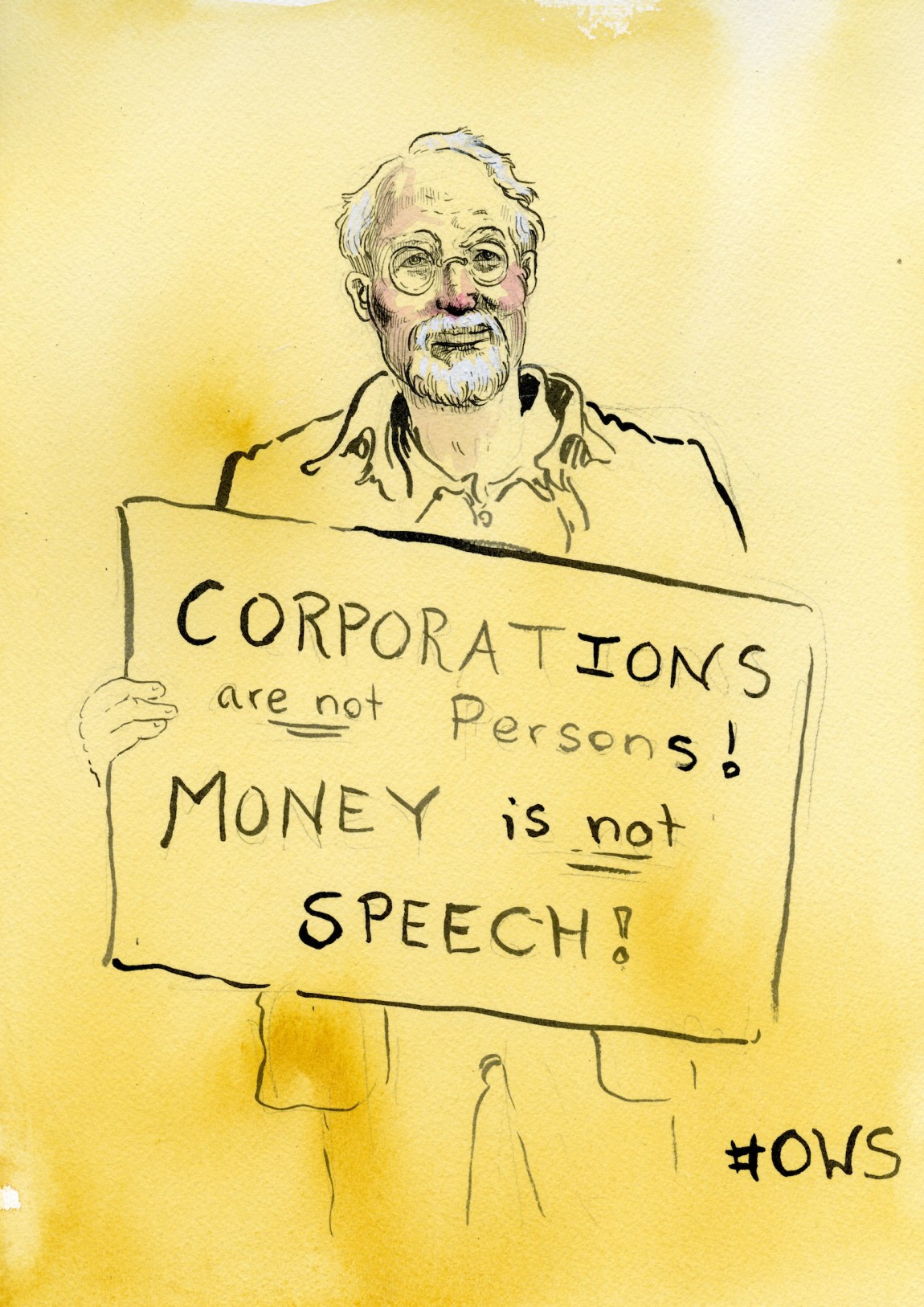

On September 16, 2021, we published Molly Crabapple’s essay “Occupy Memory,” a personal reminiscence about the movement that began—exactly ten years ago—with a protest gathering in Lower Manhattan that led to the occupation of Zuccotti Park. As she relates, Crabapple was drawn in by the unique character of its radicalism, and contributed in a host of ways—not least, by supplying artwork for posters and placards, a selection of which accompanies her article. This week, she also reflected on how we might understand Occupy Wall Street in historical perspective, and what it achieved; this was the starting point for the conversation that follows.

Matt Seaton: You identify the primary motor behind Occupy Wall Street as anger at the bailout of the 2008 financial crash, though you also connect it very aptly to other, international protest movements. But I also think of Occupy as an inheritor—in its anticapitalist orientation and in its internationalism—of the antiglobalization actions of the 1990s and early 2000s, especially the 1999 Seattle World Trade Organization protest. Do you see that, as well?

Molly Crabapple: Absolutely. I didn’t mention the WTO protests only for reasons of space (and because I was a bit too young to have been involved), but more than a few very active Occupiers had experiences in the Battle of Seattle. Another, much more proximate though less credited influence was the tragically unsuccessful movement to save an innocent Black man, Troy Davis, from being executed by the state of Georgia [in September 2011]. In New York, protests for Occupy and protests in defense of Davis often merged, and Davis’s defenders gave Occupy a better understanding of police and racism.

These earlier or allied movements often seemed to catch fire, flame briefly, then fizzle. People say the same about Occupy. What’s your underlying theory of political change, how you understand the effect of such movements?

If one views success as the existence of Occupy-branded protest camps across the world ten years later, Occupy certainly failed. But issues that Occupy championed, such as student debt forgiveness, bans on evictions, single payer healthcare, an end to the murderous war on terror, are no longer fringe. They are mainstream. This is Occupy’s success.

I’m also conscious, though, that the political left has a pathology of celebrating failure—from Spartacus to the Spartacists, and beyond—of turning heroes into martyrs and ennobling historic defeats. Is there a risk of this in memorializing Occupy? How do we avoid that?

It’s not just the left. All movements love their martyrs, who are useful by virtue of being silent. The important part is to look clearly at one’s own, and one’s own movement’s past, and to speak about them honestly.

On the other side of the ledger, perhaps, after 2011 “inequality” became a buzzword, Thomas Piketty went on the bestseller list, AOC got elected, Bernie Sanders ran two historic presidential campaigns, the pandemic bailout was very different from the 2009 one, and so on. How do you fit Occupy into all that?

Occupy broke the American taboo on talking about class. Even better, it named a clear enemy: a corrupt, rapacious, and frankly none-too-bright financial elite that they called the 1 percent, which had bought off the politicians and was sucking all the life and money out of everyone else. This was bracing stuff and, I’d argue, did much to make everything you mention possible.

I really identified with what you wrote about your queasy feeling of demonstrations’ feeling pointless and a bit embarrassing. Did Occupy change that for you permanently?

Yes. Because, for the first time since the huge anti-war demonstrations that I took part in, I saw protests that everyone was participating in. It did not feel like the hobby of a tiny, powerless subculture (however correct that subculture was). Since then, taking part in protests has felt like the rent I pay for living in this world.

As you touch on in your piece, there was a lot of grayhead eye-rolling about Occupy’s leaderless, communalist ethic, its laundry list of demands, its lack of traditional party-political structure, etc.—and this was very much part of the critique of its ultimate loss of momentum and “failure.” But it sounds as though you don’t accept this, and want to recuperate something about what was “disorganized” about Occupy as being of lasting value. Can you define that more?

I don’t know what these grayheads wanted. Did they expect Elizabeth Warren to ride in on a white horse, call a mass gathering of square-jawed truck drivers and photogenic grandmothers who would all spout perfect economic statistics and identical, incisive policy proposals, and thus, by sheer force of their rightness, end foreclosures and ruinous medical debt forever (in an incrementalistic, reformist way, of course)? I think many of the critics who dismissed Occupy were very comfortable: they had neither understanding of nor sympathy for the suffering that 2008 wrought on millions of people. So they went down to the park, found a dude in a silly hat, and used whatever he said to distract from the imperative to address that suffering.

Advertisement

In a recent piece in The New Yorker, Andrew Marantz took a deep dive into the world of organizers behind a purported “left turn”—a reversal of the neoliberal counterrevolution against New Deal America that we’ve been living through since at least the Reagan era. Yet here we are with a president in post only after the failure of a far-right insurrection to prevent his inauguration and a Congress so finely poised on knife-edge majorities that arguably a single senator has more control over his party’s agenda than Biden does. Is this really the inflection point of that left turn or the last best hope for the republic’s democracy?

The left turn is the last, best hope for the republic’s democracy.