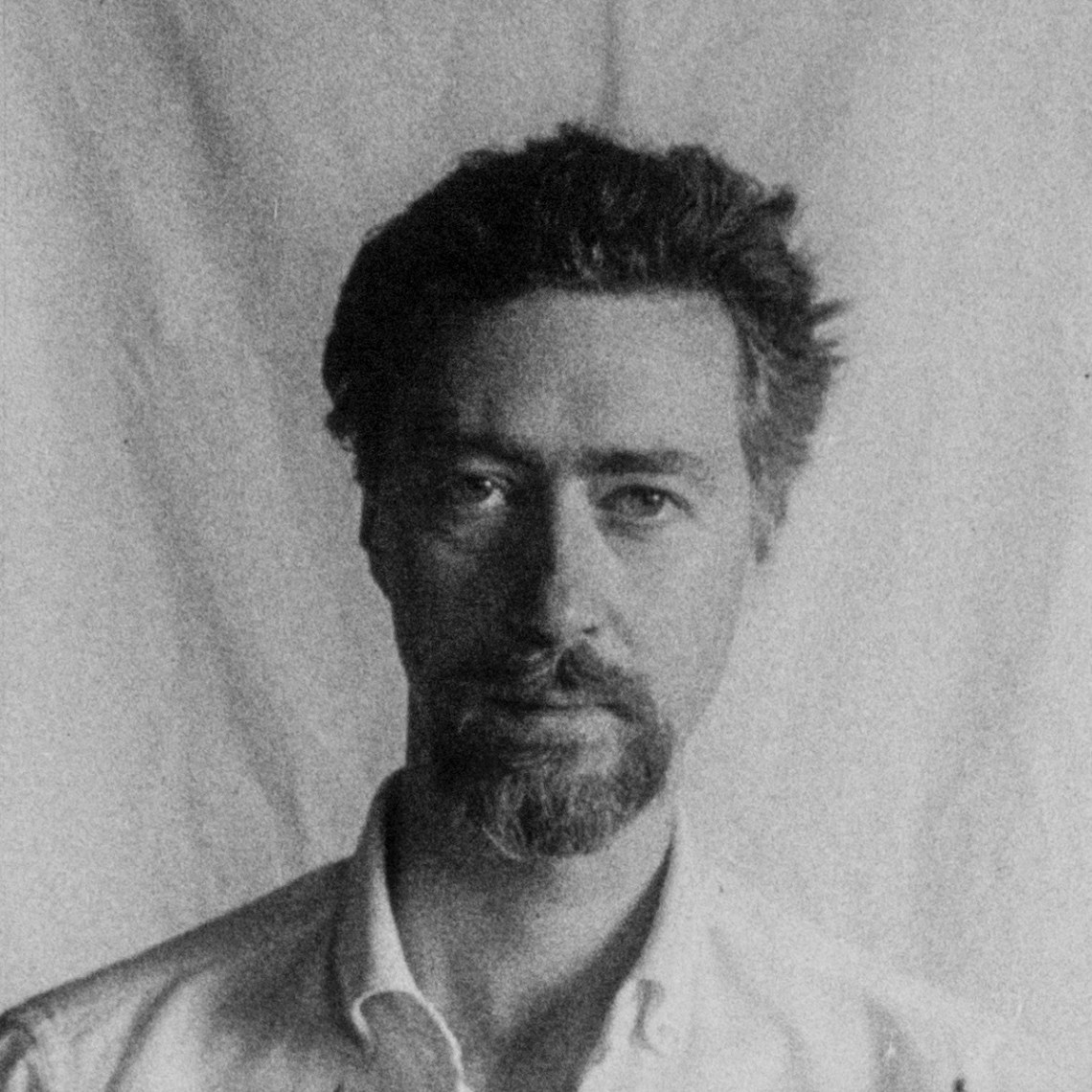

Based for most of the 1960s in Lower Manhattan, the Canadian painter, sculptor, musician, and maker of photographic objects Michael Snow was among New York’s most significant interstitial artists—associated with the New Thing jazz players who provided the soundtrack for his first important film, New York Eye and Ear Control (1964), he also acted as a bridge that connected Jonas Mekas’s New American Cinema with the serialist composers (Philip Glass and Steve Reich) and post-minimalist gallery artists like the sculptors Robert Morris and Richard Serra, who recognized in Snow an affinity for their reductive, medium-specific work.

Snow is regarded as a national treasure in Canada, especially in his hometown, Toronto, where he has been the subject of retrospectives and has created numerous public artworks. Here he is best known for his movies, in particular Wavelength (1967). Most simply described as a slow, continuous forty-five-minute zoom across a largely empty loft into a photographic close-up of gentle waves pasted between the windows on the opposite wall, it rivals Jack Smith’s quite different Flaming Creatures (1963) as the New American Cinema’s most passionately admired—and loathed—work, as well as its most influential.

Some movies are not simply motion pictures but monuments in space and time: D. W. Griffith’s epoch-hopping Intolerance (1916) is one. So is Chantal Akerman’s domestic epic Jeanne Dielman (1975). Christian Marclay’s twenty-four-hour installation The Clock (2010) and, experienced in 3D IMAX, Alfonso Cuarón’s weightless Gravity (2013) are more recent examples. The most modest and, in many ways, the greatest of these monuments is Wavelength.

Among other things, Snow devised a perfect metaphor for narrative film—the last image is implicit in the first—as well as for cinema as temporal projection. He also created a template for his subsequent films which, as demonstrated by the unprecedented full retrospective this month at Anthology Film Archives, are invariably anti-illusionist, reflexive, and often paradoxical investigations of cinema’s unique, irreducible properties.

Snow did not hit upon the conceit for Wavelength immediately. His first two films were eccentric versions of then current underground genres. New York Eye and Ear Control—which, as much as it’s about anything, concerns the adventures of the Walking Woman, a two-dimensional icon that Snow had been painting for several years, as she inhabits cinema’s faux three-dimensional world—has affinities with the anarcho-picaresque beatnik movies of Ron Rice. The more domestic Standard Time (1967), in which the camera circles, waist-high, around Snow’s Chambers Street loft, intersecting with the movements of a cat, a turtle, and Snow’s wife, the filmmaker Joyce Wieland, is an avant-garde home movie.

Wavelength led to movies that were as visceral as they were conceptual, designed to make the viewer conscious of what it is to watch a motion picture. “The cool kick of Michael Snow’s Wavelength,” Manny Farber, a downtown painter and critic, wrote in a 1969 Artforum piece, was “seeing so many new actors—light and space, walls, soaring windows, and an amazing number of color-shadow variations that live and die in the windowpanes—made into major esthetic components of movie experience.”

The centerpiece of Snow’s retrospective is a restored version of his 1969 follow-up to Wavelength, a fifty-minute film titled <– –> (also known as “Back and Forth”), a sort of perpetual motion machine or abstract ping-pong game consisting of a constant volley of motorized panning shots across a college classroom. This was followed by an even more extreme perceptual workout, La Région Centrale (1971). Running for more than three hours, it comprised seventeen choreographed shots—impossible-seeming, yet-to-be-named camera gyrations—made using a specially designed, computerized tripod placed atop a mountain in northern Quebec.

Snow made other venturesome motion pictures—Seated Figures (1988) is a landscape film produced with a camera bolted, lens down, to a metal arm extending off the back of a motor vehicle—as well as projects defined, contrariwise, by rigorous constraint. A Casing Shelved (1970) is a single 35mm slide held for the duration of a forty-five-minute taped explication of the objects in the image. So Is This (1982) is the cinematic equivalent of a concrete poem, a film-text in which each shot is a single word.

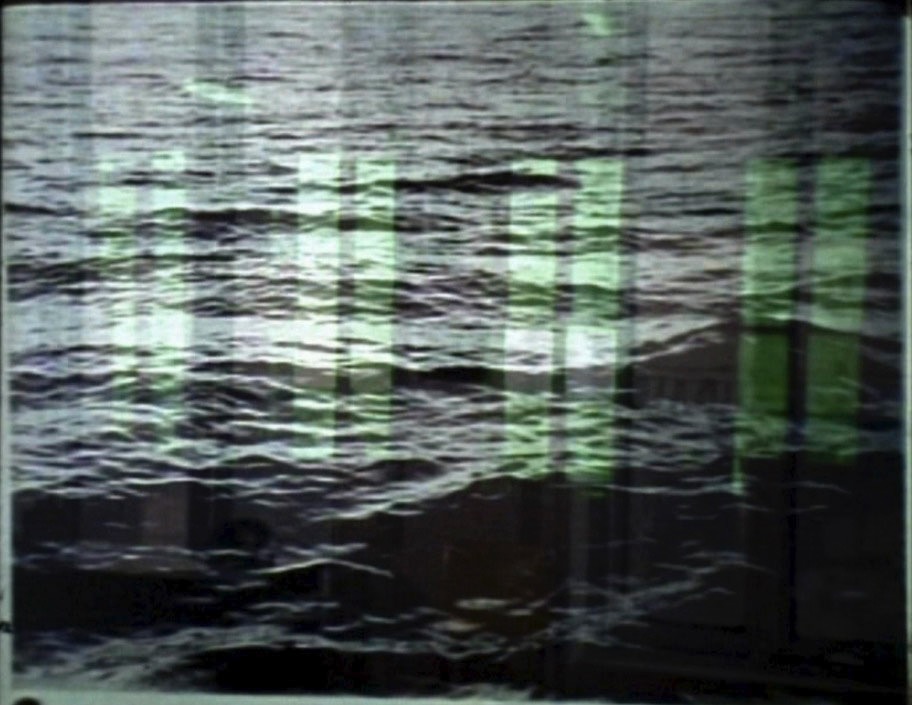

In addition to movement studies, Snow created a paean to film’s chemical basis. Named for the founder of modern chemistry, To Lavoisier, Who Died in The Reign of Terror (1991) treats a series of mundane images (a man painting, a woman cooking, a game of cards) to all manner of visual derangement by forcing chemical changes in the film emulsion. Variously scarred, light-struck, watermarked, solarized, or blotched, the footage looks as if it had been developed in a bathtub and baked in the oven. Although Snow had little control over precisely how the emulsion would be affected, the movie is, in its flamboyant visual distortions, his most expressionist.

Advertisement

In addition to New York Eye and Ear Control, which features an improvised score by Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, and others, the Snow oeuvre includes several mock performance films. Funnel Piano (1984), made in Super 8, is an improvisation in which Snow plays the piano with one hand while filming with the other. Puccini Conservato (2008) documents a stereo turntable playing a track from La Bohème. Somewhat in the same impish spirit, Snow has also made several feature-length films that, given their audiovisual jokes and sleight of hand, might be termed “perceptual vaudeville.”

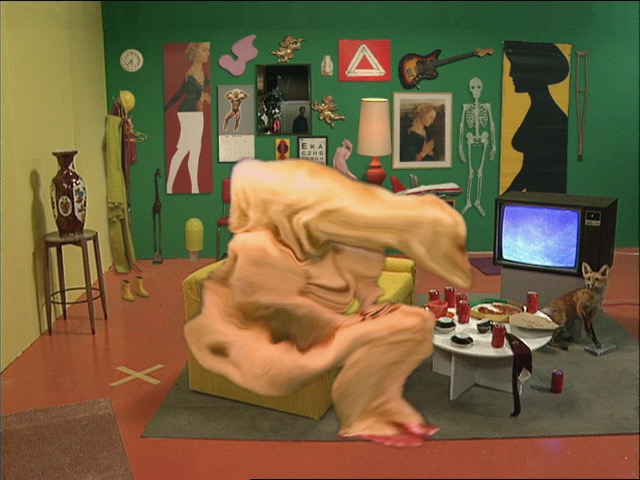

With his longest film, the four-and-a-half-hour Rameau’s Nephew by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen (1974), Snow turned his attention to the relationship between sound and image, with results that are never less than provocative and often exceedingly droll. Titled for the central region of tissue that acts as conduit between the brain’s two hemispheres, his 2002 video feature *Corpus Callosum is a bonanza of digital effects—wacky sight gags, outlandish color schemes, and corny visual puns—recalling the work of vulgar modernists Ernie Kovacs and Frank Tashlin in its playful recapitulation of the artist’s career-long interests.

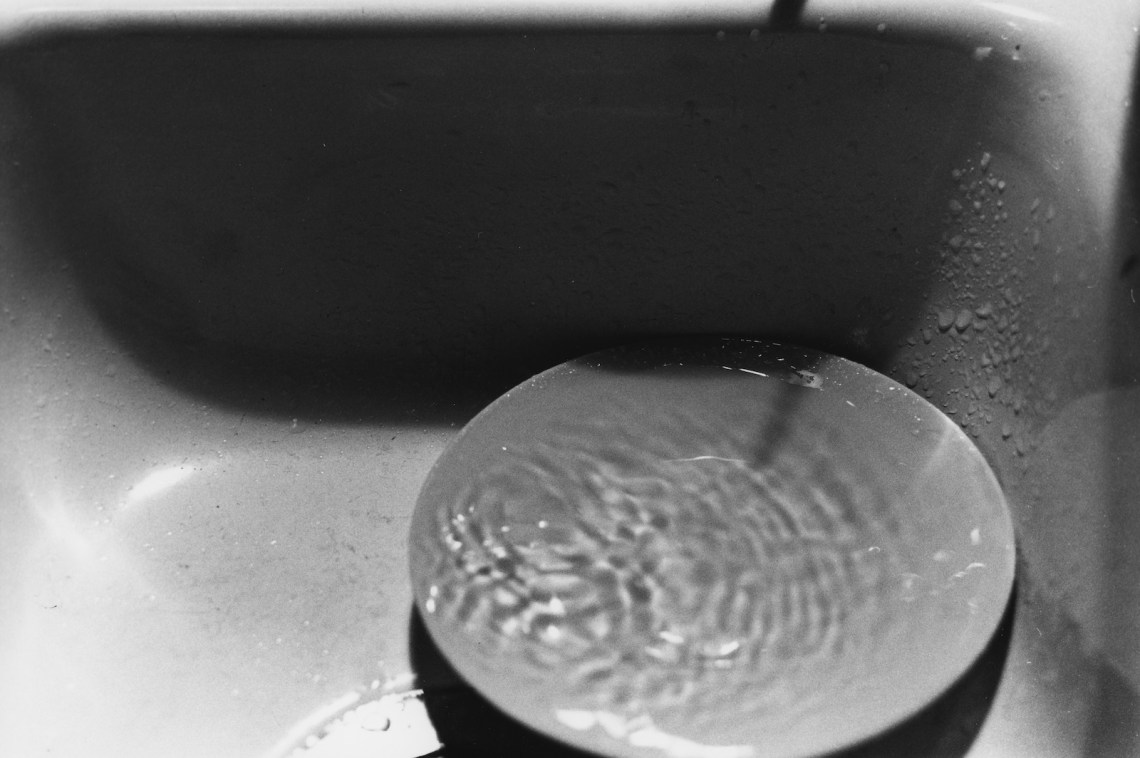

In general, Snow prefers humor to irony. Another recap of his career, Side Seat Paintings Slides Sound Film (1970), is an artist’s slide talk filmed from an angle that spatially warps the projected images, recasting rectangular canvases as trapezoids. One of several Wavelength parodies, the 1976 Breakfast (Table Top Dolly) is a fifteen-minute tracking shot down a cluttered kitchen table. Unaccountably, the camera appears to affect everything in its path—dumping wineglasses, upending orange juice containers, shoving a fruit bowl up against the wall. The moviemaking apparatus is visual only in its random physical impact.

Originally scheduled for last year, the Anthology retrospective was postponed because of the pandemic. Snow, ninety-two, is now too frail to attend. Still, I cannot imagine another artist of the minimalist, conceptual, anti-expressive persuasion whose work expresses a personality as fully as his does.