One evening this past October, I boarded a bus in the Moroccan capital of Rabat for an overnight trip north to the Mediterranean coast. After several hours, we were climbing into the Rif Mountains, the vehicle groaning and swaying on hairpin turns. A relatively recent mountain range—geologically younger than the better-known peaks of the Atlas and less grand—the Rif rises steeply from the sea in the north but falls away in gentle escarpments to the south.

The landscape appeared foreboding enough in the moonlit gloom: towering massifs carpeted with maquis, copses of cedar and fir, and deep ravines walled by limestone crags. It wasn’t hard to see how, one hundred years ago, this terrain struck fear into the hearts of young conscripts from Spain, which ruled northern Morocco as a protectorate, as they faced a fierce insurgency by the indigenous Amazigh people, also known as Berbers.

“The worst war, at the worst moment in time, in the worst place in the world,” a Spanish journalist wrote of the five-year conflict known as the Rif War.

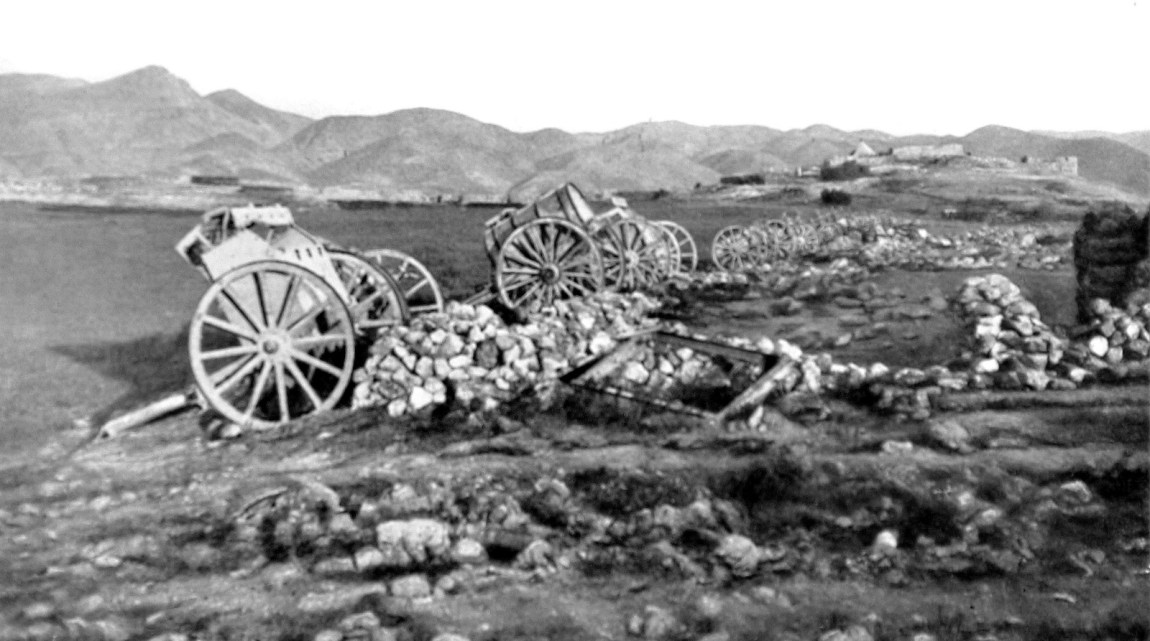

The fighting started in early June 1921 when Riffian tribes ambushed a small contingent of Spanish forces at a rocky outcrop on the northern fringe of the Rif known as Mount Ubarran. With hindsight, the engagement was merely the opening skirmish of a much more consequential and, from the Spanish point of view, catastrophic battle a month later in and around the nearby village of Annual (emphasis accented on the last syllable). The Disaster of Annual, as it is known in Spain today, resulted in the deaths of at least 13,000 Spanish soldiers at the hands of just 3,000 Riffians. Over the course of eighteen days, the fighters besieged poorly trained Spanish soldiers and native troops in sandbagged outposts depriving them of supplies and water—some soldiers resorted to drinking their urine—and cutting them down with gunfire or daggers as they retreated pell-mell to the Spanish enclave of Melilla. The Spanish field commander, a famously incautious general named Manuel Fernández Silvestre, perished in the melee, possibly by suicide. His remains were never recovered.

It was the worst military debacle in modern Spanish history and arguably the most severe defeat any European colonial army had then suffered on the African continent, surpassing even the 1896 rout of the Italian army at the Battle of Adwa in Ethiopia. Its aftermath rippled across North Africa, the Mediterranean, and Asia, reaching even the United States, where it stirred public sympathy for the Riffian cause and electrified Black American pan-Africanists such as the followers of Marcus Garvey. The centenary of Annual in July of this year went virtually unnoticed in the Anglophone world, yet it remains as a great source of pride among the Amazigh of the Rif Mountains, an unsettling legacy for the Moroccan monarchy, and a lingering national trauma in Spain.

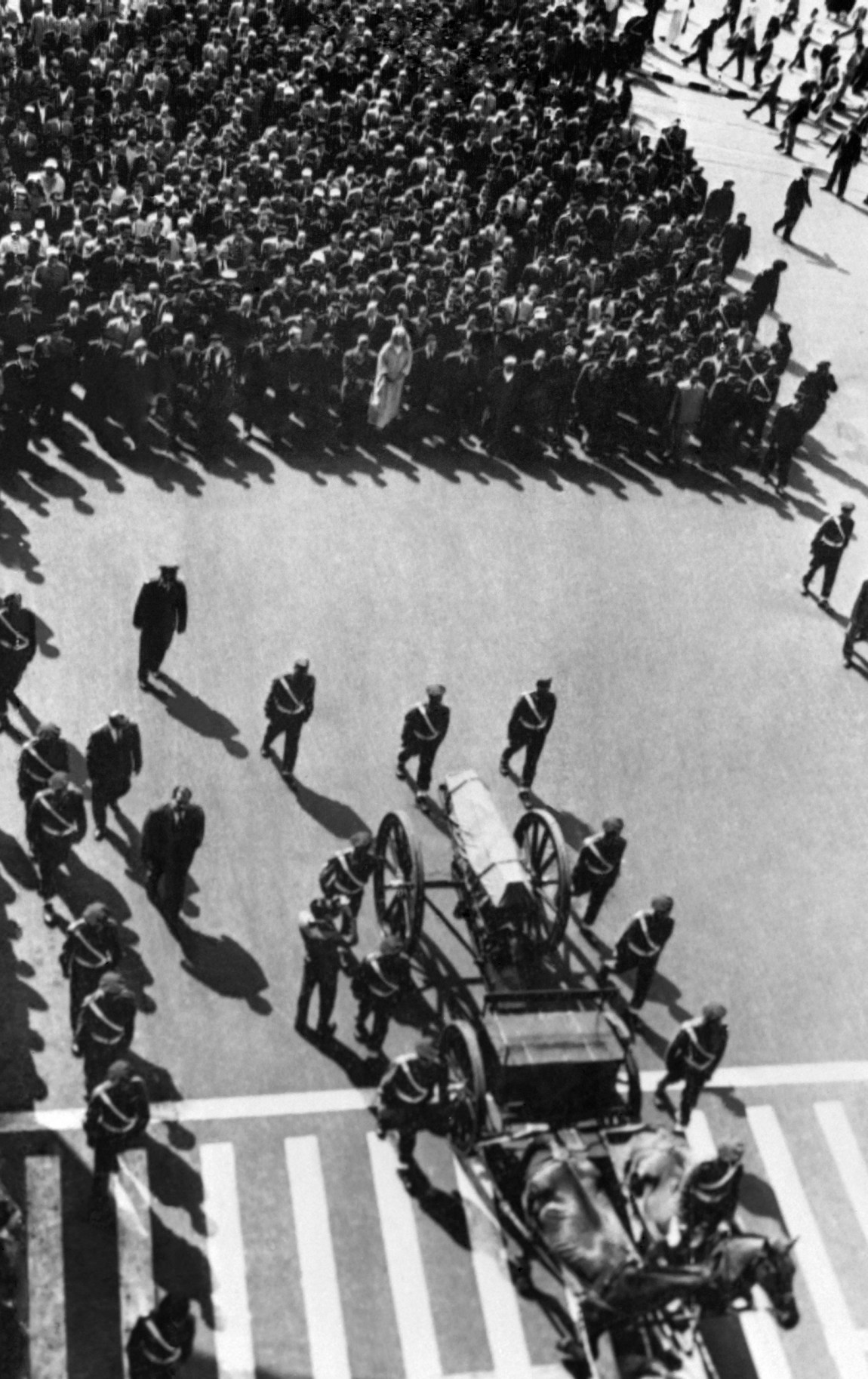

News of the rout at Annual threw Spain into a political crisis. It prompted public demands for the abandonment of the Spanish protectorate in the north that had existed since 1912 through an agreement with France, which governed the territory to the south. It contributed to the overthrow of the parliamentary government in Spain and the establishment of a dictatorship by General Miguel Primo de Rivera. And it spurred a campaign of revenge and reconquest in Morocco by the Spanish military that enabled the meteoric rise of a young Spanish officer named Francisco Franco Bahamonde.

Ascending to command the feared Tercio de Extranjeros, or Spanish Foreign Legion, the diminutive, pot-bellied future dictator would rely upon Spanish and Moroccan veterans of the Rif War as the shock troops in his assault on the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939—indeed, Franco’s first act in joining the Nationalist coup was to assume control of the Spanish Army of Africa in Morocco. Historians have argued that the earlier years of fighting in Morocco had helped forge a supremacist, authoritarian, and militarist identity among the so-called Africanista current within the Spanish officer corps—a chauvinism that later underpinned the Nationalists’ dehumanization and murderous persecution of Republicans during the Spanish Civil War.

“Without Africa, I can scarcely explain myself to myself,” Franco told a journalist in 1938.

In particular, a hardline faction within the Spanish military became determined to avenge itself for the humiliation at Annual, and in the most ruthless manner possible. The Spanish high command and Rivera’s military government decided to use chemical weapons in Morocco to overcome the Riffians’ fighting superiority. Starting as soon as 1923, and possibly earlier, Spanish forces deployed, by artillery and later by airplane, large quantities of mustard gas—then also known as yperite, after its use in the Battle of Ypres during World War I—as well as phosgene, diphosgene, and chloropicrin on combatants and civilians alike across the Rif. It was the first time in history such weapons had been used extensively from the air and against civilians, yet their deployment went largely unnoticed or without comment in the West. (Postwar efforts by the League of Nations and humanitarian organizations at getting them outlawed, as they were by Geneva Protocol in 1925, were primarily concerned with their effects on white Europeans and regular combatants, rather than on rebellious colonial subjects.)

Advertisement

Long shrouded in secrecy, this chemical warfare was the worst example of Spain’s colonial atrocities in Morocco. Until Spanish and other European archives opened up their records to researchers in recent decades, testimony about the employment of poison gas and other Spanish abuses had been limited mainly to Riffian oral traditions, such as an epic poem called the “Poem of Dhar (Mount) Ubarran,” that immortalized the Riffians’ initial victory and the travails that followed. At a public event this summer to mark its translation from Tarafit, the local Amazigh dialect, into Spanish by two Moroccan scholars, a cultural official for Spain in Melilla acknowledged how important this Riffian account was for Hispanic readers. Activists in the Rif with whom I spoke maintain that such gestures are not enough: Spain has yet to formally admit to its use of chemical weapons during the Rif War, let alone apologize or pay reparations, even though some ministers and politicians, especially leftist Catalans, have raised the issue before the Spanish parliament.

The absence of official contrition has only spurred Riffian activists, given the suspected link between the toxins contained in those weapons and the disproportionately high rates of cancer found in the Rif Mountains. Virtually every family in the area I met seemed to have lost a close relative to the disease, known as akhenzir in the local dialect. “I thought, growing up, that akhenzir was simply something you got when you turned forty,” an English professor from the Rif named Mohamed Daoudi told me.

Morocco’s ruler, King Mohamed VI, appears reluctant, however, to press the issue with the Spanish government for fear of worsening diplomatic tensions between the two countries. (These relate to other bilateral issues, such as African and Moroccan migration to the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla in northern Morocco and the Moroccan government’s desire to secure Spain’s support for its position on the Western Sahara conflict.) Yet there is another reason for the monarch’s hesitation, one that lies closer to home. For the very meaning of the Rif War, and its implications for national identity and state-building within the kingdom, are contested and deeply sensitive matters in Morocco.

*

Apart from its resounding impact on Spanish politics, the Battle of Annual catapulted to prominence the charismatic leader of the Rif’s anticolonial movement, Muhammad ibn ‘Abd al-Karim al-Khattabi. A former judge (or qadi) from a prominent Amazigh tribe and the onetime editor of the Arabic section of a Spanish-language newspaper, al-Khattabi by the summer of 1921 had rallied the frequently feuding Riffians into an effective fighting coalition.

Buoyed by the arms he seized at Annual and the ransom paid by the Spanish for the prisoners he captured, al-Khattabi and his lieutenants proved masterful guerrilla commanders in the coming years, seizing nearly all of Spanish-ruled land in northern Morocco. And between 1921 and 1926, when his forces were defeated by the combined military might of Spain and France, al-Khattabi presided over an autonomous statelet, which he called the Republic of the Rif. Replete with a ministerial cabinet, flag, courts, telephone system, and plans for printed currency, the republic declared its independence from Spain and also, implicitly, the dominion of Morocco’s sultan, who had been forced into a position of subservient collaboration with European colonial powers.

This was an embarrassing affront to the authority of the Arab ‘Alawi dynasty that, claiming divine descent from the Prophet Muhammad, had ruled Morocco for centuries. And the challenge from the region persisted for decades: in 1958–1959, not long after Morocco achieved independence, the Rif erupted in protests against the monarchy over its neglect of the impoverished region. By then, al-Khattabi was living in exile in Cairo but he remained a significant political player, issuing communiqués of support for the uprising and even appealing to Egypt’s president, Gamal ‘Abd al-Nasser, to back a revolt. The Moroccan regime responded with an unsparing crackdown led by then crown prince Hassan II, who ascended to the throne in 1961. Thousands were killed during the repressions, which—in a grim echo of colonial Spain’s war crimes—included the aerial bombardment of the Rif villages.

Advertisement

This pattern of protest in the Rif crushed with brutality recurred in 1984 as part of a broader, nationwide spell of state-led imprisonment, disappearances, and killings during the rule of King Hassan II, known today as the “Years of Lead.” Only with the king’s death in 1999, when the current monarch Mohamed VI came to the throne, was there a break in the cycle of violence. The new king made some modest economic reforms in the region and embarked on a program of reconciliation, which, though flawed, did allow for al-Khattabi’s partial rehabilitation—or, in the view of some Rif activists, appropriation—by naming of schools and avenues after him.

These cosmetic changes hardly compensated, however, for the Rif’s continued economic and political marginalization. The region remained wracked by steep unemployment and waves of emigration to Europe, circumstances that would eventually rekindle the protest movement.

In October 2016, Mohsen Fikri, a poor fishmonger in the Riffian port city of Hoceima, was crushed to death by a garbage compactor as he was attempting to retrieve a catch of swordfish confiscated by police. For many in the Rif, the abhorrent manner of his death seemed to epitomize the official callousness that had long bedeviled the region, and sit-ins and marches soon followed. These coalesced a month later into a widespread protest movement that became known as the Hirak al-Rif (Rif Movement). Its long list of demands included economic development and new infrastructure, and an end to the kingdom’s designation of the region as a “military zone.” In a renewed push for the regime to address the Rif’s historic affliction with akhenzir, demonstrators also called for the construction of a cancer treatment facility.

Once more, the youthful activists resurrected the memory and symbols of the Rif War by carrying banners emblazoned with al-Khattabi’s portrait and quotes and waving the flag of his Rif Republic. In contrast to the past, however, this latest iteration of dissent was amplified by diasporan networks and social media. “This new generation has more than enough tools to make the palace listen,” a young female activist and entrepreneur from Nador, a Riffian coastal town, told me.

Still, the regime accused the protesters of sedition and separatism. Up to a thousand were arrested, many simply for expressing support on Facebook, and dozens have alleged that they were tortured while detained. Some remain in prison to this day, while others have fled the country and never returned.

*

Shortly after midnight, somewhere high in the Rif, the bus lurched to a halt at a police checkpoint. Informed in advance of the schedule and the passenger manifest, officers boarded, strode down the aisle, collared a young Moroccan man, and escorted him off the bus. We waited while he was questioned in a windowless van for half an hour; his interrogation apparently over, he was able to resume his place on the bus, and we set off once again. This was just a preview, I would learn, of the security gauntlets that ring the towns of the Rif—restrictions that had reportedly tightened owing to the pandemic.

Arriving in Hoceima at dawn, I walked to its expansive plaza overlooking the Mediterranean. It was along these shores in 1925 that the Spanish and the French staged a large amphibious landing involving tanks and air support that marked the beginning of the end for al-Khattabi’s Rif Republic. To the north of the plaza was the courthouse and police station where residents had gathered on the night of Fikri’s death in 2016.

I met Farid El Hamdaoui, a forty-eight-year-old teacher, for coffee in the plaza. He had attended that vigil. “We were shocked when it happened,” he told me. “I stayed up until 5 AM.”

Over the months of demonstrations that followed, he succeeded in slipping the security forces’ dragnet, but his nephew was not so lucky. Arrested in 2017, the younger man was shuttled between prisons in the Rif and Casablanca for three years, prompting his uncle to organize, along with the families of other detainees, an effort to win their release. At the same time, El Hamdaoui shifted his activism to another, more subtle, and arguably more powerful medium.

Outside of his teaching job, he is the vocalist and lead guitarist for a three-person band called Rifana, which he says aims to “renew” the traditional music of the Rif. It does so in a style that he describes as a fusion of reggae and centuries-old Amazigh songs, including the “Poem of Dhar Ubarran.”

“The kids listen to it and think they are hearing something new,” he told me. “In fact, it is actually quite ancient in origin.” Most of the lyrics he sings are not overtly political, though El Hamdaoui sees it all as part of “an artistic, cultural, historical, associative, and medical struggle.”

The latter bit is very present for El Hamdaoui. The day before we met, his fifty-five-year-old mother-in-law had died of cancer; and she was by no means the first relative he’d lost to the disease. Although he acknowledged that the full epidemiology needs further research, one of his more plaintive songs, “Thithet,” or “Truth” in Tarifit, lays the blame squarely on the toxic legacy of the Spanish chemical weapons used during the Rif War:

We know the whole truth

But we want you to confess and reveal everything

Just as the pain in my heart speaks of the many torments it has endured

Just as roses grow on the graves of the victims who fell from your crimes.

El Hamdaoui is not the only artist who has drawn on the Rif’s colonial experience to cast a harsh light on present inequities. A recently published novel, The Dawn Gates by Mustafa Oueriaghli, narrates the ordeals of a family torn apart by the dislocations of the Rif War and the predations of the Spanish. In his 2017 feature film, Iperita (Spanish for yperite), the film director Mohamed Bouzaggou depicts a Spanish air force veteran who, anguished by guilt, travels to the Rif decades after the war to seek the forgiveness of the locals. The Riffian villages he visits are places of desolation, blighted by official indifference and their poisonous inheritance. In one scene, a Moroccan teacher arrives from outside the Rif to take up a post in a scruffy classroom that holds just three students. “Everyone’s dead, who is going to make children?” he is asked.

A few miles east of Hoceima lies the town of Ajdir, bombed repeatedly by the Spanish, including with chemical munitions, before being captured and looted by Spanish troops. Once, al-Khattabi himself had lived here, when the town was the de facto capital of his Rif Republic. Today, all that remains there is an administrative building the Spanish subsequently erected, itself now a concrete shell defaced by graffiti and overrun with weeds and olive trees, though for Rif activists the site is a hallowed space.

“Abd al-Krim al-Khattabi had a radical interpretation of what an independent Morocco should be,” a Moroccan anthropologist named Zakaria Rhani told me later, in Rabat. “And so, too, do the Hirak [al-Rif] activists. In raising his flag, they were expressing a new, more subversive way to belong to Morocco.”

Rhani is part of a team of Moroccan researchers studying collective memories of colonial and postcolonial violence in the Rif. The fieldwork for the project has been fraught with risks; Moroccan security services harassed his colleague who was conducting interviews in the region, while suspicious Riffians quizzed her on the details of classic ethnographies of the Rif in order to verify her scholarly bona fides and ensure she herself was not an intelligence agent.

I asked Zakaria about the Battle of Annual and the complaints I’d heard from Riffian activists that the Moroccan regime had downplayed the centenary. I’d earlier gone to the site of the battle. All that stands in the barren valley around the village of Annual is a modest stone memorial summarizing the victory in Arabic. Nearby is a small plaque that reads, “Remember Your History,” in Arabic and in Tifinagh, the script used to write Amazigh languages. But whose history is it?

“Annual has been nationalized,” Zakaria elaborated. “We can’t say it isn’t celebrated at all…it is just celebrated differently. The state celebrates it but without specifically saying who effected the victory.”

The clearest illustration of this ambiguity for me was the Moroccan government’s announcement in October of a postage stamp commemorating the battle. The painting in the stamp depicts a figure with al-Khattabi’s likeness atop a white horse, looming over panic-stricken Spanish soldiers, against a backdrop of hilly terrain and distant fighting. Such iconography has provoked criticism among Amazigh activists from the Rif.

“The painting is all wrong,” an education official from Hoceima named Abdelmajid Azuzi told me. It was done in an Arabized style, he explained, pointing to the horse. “Nobody rode horses in the Rif War…these were mountains after all,” he chuckled.

The intention of this aesthetic choice, he said, was insultingly clear: to obscure the distinctiveness of the Riffian and Amazigh contributions to Morocco’s anticolonial struggle and to portray the Moroccan monarch as a stand-in for al-Khattabi.

*

Throughout the war that followed his victory at Annual, al-Khattabi had hoped that US citizens would see in his struggle against Old World colonialism similarities to their own revolutionary fight for independence centuries before. This proved, by and large, a correct assumption, thanks in part to sympathetic coverage of the Riffian resistance by American reporters, especially Vincent Sheean of The Chicago Tribune who made two arduous treks to the Rif and interviewed al-Khattabi. The Riffian leader’s face appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1925, and the struggles of his self-styled republic prompted the formation of a charitable organization in Massachusetts, the American Friends of the Rif. Al-Khattabi even inspired a Broadway operetta. Still, Washington’s policy toward the conflict was one of strict neutrality.

It was a position that the French sought to change, having intervened in the Rif War in 1925 on the side of the Spanish after France’s own Moroccan protectorate, sometimes known as the Empire Chérifien, was threatened by al-Khattabi’s incursions farther south. Facing a personnel shortage in its military, especially of pilots, and eager to shift American opinion in its favor, Paris resorted to a public relations gambit.

In the summer of 1925, the French military recruited a group of sixteen American aviators, some of whom had served with French forces during World War I. Dubbed the Escadrille de la Garde Chérifienne, the squadron’s members were nominally attached to the armed forces of the Moroccan sultan, even bearing the sultanate’s emblem of a five-pointed star on their uniforms. In reality, though, the pilots reported to the newly arrived French commander in Morocco, Marshal Philippe Pétain, the “Lion of Verdun” who would later be the figurehead of the Vichy regime in World War II.

The leader of the American outfit was a soldier of fortune named Charles Sweeny. A “ruddy, hawk-faced” San Franciscan and the son of a wealthy industrialist, according to a 1940 New Yorker profile, Sweeny had been expelled twice from West Point for disciplinary infractions. He had then served in the French Foreign Legion during World War I, in which he was severely wounded and decorated for bravery. In postwar Constantinople, he met Ernest Hemingway, who would become a close friend over the next two decades. But in an August 1925 letter to Gertrude Stein, the writer poked fun at Sweeny’s motives in aiding the French during the Rif War, even suggesting Sweeny had picked the wrong side:

Charley Sweeney [sic] and collection of former Capts, Majors, Lieut. Cols. off to fight the Riffs. Awfully sweet thing to do. But if you’ve got the Legion of Honor already what’s it all about? Can understand fighting for Abd-el-Krimmy [sic] against the French altho not attractive but to deliberately go and fight for [the French] in Morocco—not for adventure or whats in it—oh no—for high moral purposes. You have to admit it is touching.

With the colorful war hero Sweeny at the helm, the French had hoped that the squadron would win favor among the American public and in the American government. In fact, the scheme backfired spectacularly. The mercenaries did indeed conduct numerous missions in support of the French during their short deployment—up to 470, by one count. But many of these sorties involved the deliberate bombing of civilians. As one of the American aviators, Paul Ayres Rockwell, admitted in his diary: “It became part of our task to go over and bombard the villages that had escaped destruction…to try and terrorize them into abandoning Abd-el-Krim’s cause.”

Throughout the month of September 1925, the Escadrille bombed the town of Chefchaouen, in the western part of the Rif Mountains known as the Jbala. Originally established, in 1471, as a fortress against a Portuguese invasion, it soon became a refuge for Muslims and Jews fleeing Spanish persecution in Andalusia. Over the centuries, the town acquired something of a sacred status thanks to its numerous Sufi orders, mosques, and mausoleums. Today, it is mostly known among foreigners as an obligatory though out-of-the-way stop on Morocco’s tourist circuit, famed as the “Blue City” after the azure- and indigo-painted buildings of its old quarter.

Walking through its streets one afternoon, I found little sign of the destruction that befell Chefchaouen during this brief, lesser-known episode of American military adventurism, save for the minaret of a mosque that, I learned from locals, had been bombed and then repaired in an architectural style that differed from the others. At a seventeenth-century zawiya, or Sufi school, I met a septuagenarian Islamic scholar, historian, and former city councilor named Ali al-Raisuni.

“We call 1925 ‘The Year of the Airplane,’” he told me in the tiled courtyard of the school, referring to the oral histories that had been passed down about the Americans’ raids on the town and the defenders who fired back, armed only with rifles.

The French had singled out Chefchaouen, al-Raisuni explained, because it was the “nest of the jihad”—a hub of material and moral support for the Riffian resistance. By the time the town was bombed, however, the main guerrilla force had fled, and it was mostly civilians who died. To memorialize the victims, he had approached the city of Guernica in Spain, site of the notorious fascist blitz of 1937 that inspired Pablo Picasso’s painting, for a joint resolution against terror bombing.

As was later the case with the Basque city, the backlash in the United States—then largely under the sway of Wilsonian liberal internationalism and seeing itself, albeit myopically, as an anticolonial voice on the world stage—against the bombardment of Chefchaouen was swift and fierce, contributing to the French disbandment of the squadron in November. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg threatened the American aviators with legal penalties, including imprisonment and loss of citizenship, for violating US laws. Meanwhile, editorial pages in newspapers across the country lambasted the mercenaries for killing civilians and for embroiling America in a colonial war of aggression against a people with whom the US had no quarrel. “American Bombers and Rif Babies” ran a headline in Literary Digest. “[F]or these American soldiers of fortune, war in Morocco is plain murder,” opined the Seattle Union Record.

“It is unspeakably dirty business,” echoed the Pittsburgh Post. Sweeny and his fellow adventurers, the article continued, “would have been acting more in keeping with the spirit of their native land if they had volunteered to fight for the Riffians, instead of against them.” An even more explicit call to aid the Riffians came from Negro World, the newspaper of Garvey’s pan-African Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

“Colonel Charles Sweeney [sic], an Irishman, has thrown down the gauntlet to Africans the world over,” an essay argued, shortly after the Chefchaouen raid. “If, as Mr. Sweeney avers, this is a white man’s war, this writer also believes it is a black man’s war.” The article concluded with a plea for a “contingent of African volunteers from America to battle the French.”

This exemplified the sustained sympathy for al-Khattabi’s movement among pan-Africanist and Black American voices. In issue after issue throughout the 1920s, and especially during the war’s pivotal year of 1925, Black newspapers across America lauded the Riffian fighters as exemplars of anticolonialism and African liberation. Garvey’s UNIA was particularly active in its support, highlighting the war in its meetings in Harlem and other cities.

Yet Black writers were also attuned to the limits of African solidarity exposed by the conflict. The Baltimore–based Afro-American applauded al-Khattabi for trying to set up “an independent black nation in North Africa,” but lamented that the Riffian leader was being beaten back by “black men themselves”—the Senegalese colonial troops the French employed in their campaign against the Riffians.

“This affair muddles up things,” echoed The Chicago Defender, another prominent Black newspaper. “Black may be called by white to fight black for white supremacy.” Despite this, the author went on to tell Black American readers that they did indeed have a “representative” among the Riffians.

The newspaper was referring to a twenty-year-old Black man from San Francisco named Wesley Williams who, during a spell of wanderlust and penury, had joined the French Foreign Legion in Bordeaux but then deserted in Morocco to join al-Khattabi’s forces. News of Williams’s involvement was first reported by The Chicago Tribune’s Sheean, who had encountered him during a 1925 reporting trip to the Rif. A “sharp-witted and likeable young mulatto,” according to Sheean, Williams provided the American journalist with medical care (for a bout of malaria) and told him that he was working on construction projects in al-Khattabi’s base at Ajdir. For the author of the Defender article, of course, Williams served a valuable rhetorical purpose: as a Black American foil to the white and affluent Sweeny, who was fighting Africans on behalf of the imperialists.

Williams was an unwitting harbinger of a more robust internationalism that would crystallize a decade later, when Black Americans organized recruitment and fundraising drives to defend Ethiopia (then known as Abyssinia) against the Italian fascist invasion of 1935–1936. Prevented from taking an active part in the fighting of the East African war by US laws, nearly a hundred Black volunteers would quickly find in the Spanish Civil War a similarly worthy struggle abroad against the racial injustice and oppression they faced at home, joining about three hundred other American men and women who risked criminal prosecution to aid the beleaguered Republican government. “This ain’t Ethiopia but it’ll do,” a Black American member of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion, the racially integrated American volunteer unit fighting the Nationalists, wrote in a short story.

Upon arriving in Spain, however, these Black volunteers and their supporters—most notably, the poet Langston Hughes, who covered the war as a newspaper correspondent—were anguished to find, once again, fellow Africans in the enemy’s ranks: the tens of thousands of Moroccan soldiers who served under Francisco Franco. “I know that Spain used to belong to the Moors,” Hughes wrote in a 1937 dispatch for the Afro-American. “Now the Moors have come again to Spain as cannon fodder in the fascist armies.”

*

With al-Khattabi’s defeat in 1926, the Riffian armed opposition all but collapsed, though sporadic clashes would continue into the following year. A decade later, in launching their mutiny against Spain’s Second Republic from its protectorate in northern Morocco, Franco and his army conspirators relied heavily on long-serving Moroccan troops of the Army of Africa, the so-called Regulares, and other native auxiliaries. They also enlisted additional soldiers from Morocco, including from the Rif, with some members of al-Khattabi’s tribe even joining Franco’s personal guard.

This tragic and ironic coda to the Rif War persists to this day as a source of discomfort for people in the region. Some Riffian recruits to the Nationalists’ side were already longtime collaborators with the Spanish and others were coerced. Many, however, appear to have been drawn simply by Franco’s financial inducements and the imperative of survival; by the mid-1930s, drought and poor harvests had pushed the Rif to the brink of famine. Added to this, Franco plied the Riffians with propaganda about a Catholic-Islamic coalition to fight the “godless” Spanish communists and anarchists among Republicans, though how effective this messaging was remains a subject of debate among historians.

For his part, al-Khattabi was exiled by the French to the island of Réunion in the Indian Ocean soon after his surrender. He would never return to Morocco. In 1947, while transiting the Suez Canal en route to southern France, he escaped French captivity by jumping ship and found asylum in Egypt. Al-Khattabi died in Cairo in 1963, at the age of eighty-one, and is buried there, despite calls by Rif activists on the Moroccan monarchy to seek the repatriation of his remains.

Aside from his animating effect on successive uprisings in the Rif during his lifetime, al-Khattabi’s legacy continued to be felt beyond Morocco. Setting up a Committee for the Liberation of the Arab Maghreb in 1948 in Cairo, he sought to lend political and military assistance to anticolonial struggles across North Africa. His irregular warfare campaign was cited approvingly by the Chinese revolutionary leader Mao Zedong, and it apparently also influenced some of the battlefield tactics of the Cuban Revolution (1953–1959). Fidel Castro and his early cohort of fighters, including Che Guevara, took instruction in guerrilla warfare in Mexico before the famed Granma expedition from a Cuban-born Spanish Foreign Legion veteran named Alberto Bayo, who had himself fought in the Rif War. Taking what he had learned from his encounters with al-Khattabi’s forces, Bayo taught them “what a guerrilla fighter should do to break through perimeter when he’s surrounded, on the basis of his experience of the times Abd el-Krim’s Moroccans, in the war in the Rif, broke through the Spanish lines,” Castro told his biographer.

As for Wesley Williams, the Black American legionnaire with the Riffians, he all but disappears from recorded history, reappearing only briefly in Vincent Sheean’s memoir, which was published in 1934. There, Sheean describes receiving a letter from Williams years after the Rif War. Recaptured by the French at the conclusion of the conflict, he was spared from a firing squad only through appeals by the State Department, and eventually made his way back to California’s Pacific coast.

“He had taken a job as a steward on steamer,” Sheean writes, “and thought of his days in the Legion as something strange and improbable that had happened to somebody else.”