This article is part of a regular series of conversations with the Review’s contributors; read past ones here and sign up for our email newsletter to get them delivered to your inbox each week.

In our March 10, 2022 issue, Nick Laird reviewed Whatever You Say, Say Nothing, a book about the Northern Ireland conflict by the Magnum photographer Gilles Peress (with text by Chris Klatell). A novelist and poet who today teaches at NYU, Laird grew up in the northern County Tyrone. A student at Cambridge in the mid-1990s, the final years of the Troubles, he switched from legal studies to English. After graduating, though, Laird switched back to law—and it was as a lawyer that his career most directly intersected with Peress’s work.

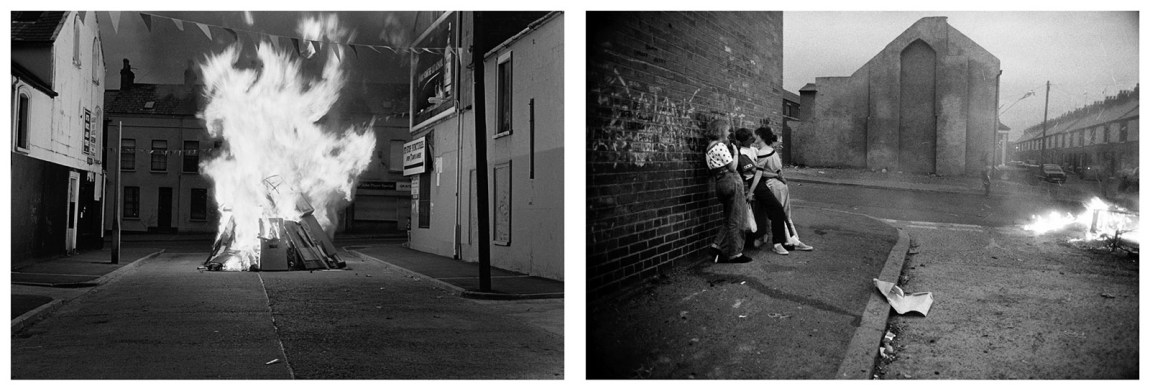

Peress was photographing a civil rights demonstration in Derry in January 1972 that turned deadly when British paratroopers, ostensibly on hand to prevent sectarian violence, fired upon unarmed protesters, killing thirteen (a fourteenth died several months later). The affair, most memorably documented in Peress’s images, became known as Bloody Sunday; it was a turning point in the conflict, helping the Irish Republican Army to justify its armed struggle and, evidently, sealing Peress’s sympathies.

Laird worked on the UK’s main official inquiry into the shooting, begun in 1998 under Tony Blair and finally published in 2010 as the Saville Report, which found that the soldiers were not in danger when they’d shot civilians and had lied to cover up their actions. It was a shameful episode for the British state, one that no effective judicial process has ever remedied. Yet, as Laird explains in his review, over the Troubles’ three decades it was the IRA that killed most—responsible for nearly half of all deaths. And Laird is sharply critical of what he sees as Peress’s partisan sympathies for the Republican cause, finding the photographer far too “enamored with casual glorifications of murder.”

Given Laird’s personal stake in the story and the astringent conclusions he draws about a celebrated photojournalist’s account, we wanted to explore further some of the issues he raises. What follows is an edited, condensed version of our e-mail exchange this week.

Matt Seaton: The anger in your review is sometimes quite palpable—anger at the lionization of murderous terrorists. How do you account for Gilles Peress, a French photographer, and Chris Klatell, an American lawyer, getting the Northern Ireland conflict so wrong? And is this part of a larger syndrome you’ve seen elsewhere?

Nick Laird: I wouldn’t presume to account for Peress’s or Klatell’s attitudes toward the Troubles beyond what I’ve noted in the review, but in general there’s a tendency (particularly among men, and perhaps among men who’ve led fairly safe and advantaged lives) to romanticize certain kinds of violence, at least until it lands on their doorstep. And many Americans did sentimentalize what happened in the North of Ireland in those years, and sponsored—in the form of Noraid [the Irish republicans’ US fundraising organization]—the murder of many ordinary people. September 11 was a wake-up call for that lobby in some ways, when terrorism suddenly became a bad word with painful, real-world results, rather than something you could sing teary-eyed songs about from an ocean away.

You mention Patrick Radden Keefe’s 2018 book Say Nothing—its title, too, drawn from an IRA poster, made famous in a poem by Seamus Heaney—as a “masterpiece” about the conflict, even though his book, too, in its way, concentrated on only part of the story—the drama of militant republicanism and the IRA. What makes it so different?

He tried to tell the whole truth, I think, and instead of glamorizing the indefensible, simply said what happened. The book’s an extraordinary feat of research and though it does concentrate, ostensibly, on one part of the Troubles, it actually covers a great deal of history. One thing leads to another, as it must.

That book also helped me understand how there had been, in mainland Britain, a constant low-level awareness of the Troubles that was really a kind of non-awareness—that the Troubles were just part of British life: an inconvenience, among others. Radden Keefe’s book sharpened the realization that the UK had been fighting a decades-long dirty war on its own doorstep. Is that right, or how do you see it differently?

I had a kind of intensified version of what you’re describing. The Troubles—the militarization, the terrorism—were normalized: for people my age in the North, it was the only thing we’d known. I suppose the army to me were the ones trying to stop the terrorists on both sides from bombing or killing, although they could be an intimidating and frightening presence. I was also aware that the squaddies, who might stop you in the road at night or you might find hiding in your garden, were just kids, not much older than we were.

Advertisement

But as I got older and began to learn the history of Ireland and England, and the shoot-to-kill policy came to light, or I worked on the Bloody Sunday inquiry, or read books like Anne Cadwallader’s Lethal Allies (about how the British forces collaborated with loyalist terrorists), it grew impossible not to see it as a dirty war. Still, most people—and I include the vast majority of the police in that designation—just wanted to live a normal existence.

In your earlier article for the Review about Brexit and Northern Ireland, you sketch your upbringing amid the Troubles, and you emphasize the psychic toll they took on so many. How do you think all of that has marked you yourself?

That’s a short question with a long answer, but in brief, the weirdest things can seem normal when you’re growing up, and it’s only in hindsight you realize what an odd, militarized, segregated existence it was. Obviously, there were the bombs and bomb scares and people being shot, but also small, distinct fears: I remember being turned back from going to school one day by loyalists in balaclavas with baseball bats who’d closed the town in protest of the Anglo-Irish agreement, or coming back from a cousin’s wedding and having to drive around a burning car and being worried in case it exploded. Losing people in bombs. The windows shaking, and so on.

I think it’s made me interested in facts, which is partly why I became a lawyer, and this is not a great moment in time for those interested in facts. It’s all about feeling. And I think growing up in the North taught me that patriotism and many other modes of “belonging” can be dangerous excuses for hostility.

In Northern Ireland, there are still segregated schools, and no serious attempt at nationwide integration has yet occurred, though that would seem such a simple and obviously beneficial move. In the US, seeing various kinds of segregation being propagated by the left, as well as the right, has been painful.

Also, I think growing up in the Troubles means I have little patience for the kind of mindset that argues silence is violence or whatever: violence is violence. Wise up, as they say in Tyrone. On earth, indifference is the least we have to dread from man or beast, as Auden puts it.

You mention in your latest review that there’s been no truth-and-reconciliation process in Northern Ireland, and yet…the peace has held now for nearly a quarter-century. How do you account for that?

People much prefer it to what came before, and there are various incentives for things not to go back to the way they were. The Good Friday Agreement was a fudge in lots of ways, but a fudge everyone could live with. There’s still a lot of organized crime in the North, which is what many of the terrorists were involved in all along.

I think of myself as Irish, but it would be untrue not to also consider myself in some ways British. There are a lot of Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland who think like that, who can survive amphibiously, as it were. I have two passports, and as it happens, I’m fairly agnostic about what happens politically, though I think a united Ireland will and should happen, even if the details will take much ironing out.

Our family always viewed partition as a disaster—it split my father’s family, and saw my mother’s chased out of West Cork, from where they made their way to Armagh—and partition meant a pluralist Ireland became two singular states in thrall to separate religious power blocks. But how could one not have sympathy with all the ordinary people, Protestants and Catholics, in the North? They have suffered a great deal. As far as sides go, I’m on the side of life. Growing up in the Troubles and losing friends to IRA bombs and having relatives shot, this perhaps leaves you inoculated against certain types of idealism and ideology.

The right to rule has been won by force. And that force hangs around: as Gerry Adams famously said, referring to the IRA, “they haven’t gone away, you know.” Those in Northern Ireland know there are two forces—the one that kills, and the one that just hangs like a miasmic fog over the country, waiting to concentrate itself into some kind of solid.

There will be no truth commission, and when the truth’s hidden or disguised, its place is taken by a kind of deception that paralyzes everything. (In Greek tragedy, the hidden crime invariably gives birth to a new crime that resembles its predecessor.) When murderers are rehabilitated without admissions of guilt, and history’s rewritten, a new and awful reality occurs.

Advertisement