What do moving pictures reveal and what can they remember? These are questions that Sergei Loznitsa’s new documentary, Babi Yar. Context, asks the viewer as well as itself.

Loznitsa is Ukraine’s leading filmmaker as well as its most outspoken. Having quit the European Film Academy over the organization’s tepid response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he was also recently cast out of the Ukrainian Film Academy after expressing support for antiwar Russian directors. Loznitsa has made some remarkable feel-bad comedies—most recently, Donbass (2018), a brutal, prescient farce about the war in eastern Ukraine—but he is most notable for his work with archival footage. The Trial (also 2018) reconstructs a show trial from the early 1930s; State Funeral (2019) draws on material intended for a never-completed official feature documenting the March 1953 funeral of Joseph Stalin.

Neither film has a voiceover; there are occasional intertitles, but the footage itself is allowed to stand as evidence. State Funeral has been criticized, most strenuously by Masha Gessen in The New Yorker, for waiting until the final titles to call attention to the magnitude of Stalin’s crimes. But withholding this information reflects the veracity of the stupefying spectacle that precedes it: the mourning multitudes didn’t know or didn’t care to know the truth. So it is, too, with the story of Babyn Yar.

Babyn Yar, or Babi Yar, is the name of the barren, sandy ravine in the outskirts of Kyiv where, over the course of two days in September 1941, the German army massacred more than 33,000 Ukrainian Jews. (After this baptism in Jewish blood, the ravine served as a killing ground for tens of thousands of POWs, partisans, Rom, and more Jews.) Never filmed and hence impossible to show, the initial atrocity occurs midway through Babi Yar. Context. It can only be represented by the events that preceded and followed it—hence, Context.

Comprised of some two hours of material culled from Russian, Ukrainian, and German archives, Babi Yar is as strategically taciturn as Loznitsa’s earlier documentaries. The footage is largely silent but the film is not. Loznitsa makes occasional use of radio broadcasts but more frequently orchestrates a ghostly, painstakingly synchronized aural accompaniment that includes a subtle mix of ambient explosions, crowd noises, cries, and, thanks to skillful lip-reading, even dubbed commands. This is a risky strategy that renders footage both more and less naturalistic, in a manner comparable to that of 3-D movies. It also adds a dimension of immediacy that makes the documentary seem not so much a recording as a transmission. While intertitles give dates and locations, no sourcing is ever provided for images, thus leaving the viewer to puzzle out which material is drawn from official Nazi or Soviet newsreels and which was taken by German soldiers, a number of whom were amateur photographers assigned to Propaganda Units.

The film begins with bombs dropping from the skies on a bucolic landscape; they are followed by the arrival of the German army, by burning villages and corpses decomposing in the fields. The muffled, distanced sound suggests a Martian-eyed view of war that could almost be science fiction. The same applies to the images of what might be called everyday occupation—although some images are not so everyday, such as the orchestrated enthusiasm with the German conquerors are greeted in Lviv and later Kyiv.

Shocking as it may be to see ecstatic crowds welcoming the Nazis with sieg heils and bouquets, it’s useful to know that Lviv (formerly Lvov and before that Lemberg, a Hapsburg city then largely Polish with large Jewish and Ukrainian minorities) was part of Poland until the Soviet occupation of 1939: for some inhabitants, the arrival of the Germans meant throwing off the Bolshevik yoke. Another piece of information withheld: further east, nearly four million Ukrainians had died of starvation during the Soviets’ forced collectivization and the ensuing famine of 1932–1933.

Germany’s amateur filmmakers document a Ukrainian militia rounding up Jews and staging a pogrom, as well as bizarrely cheesecake images of barefooted Ukrainian women digging trenches. Are they preparing mass graves? A vast holding area, teeming with prisoners, suggests an outtake from Cecil B. DeMille’s cast-of-thousands The Ten Commandments. More overtly propagandist in their search for local color, German newsreels often focus on those Russian prisoners of war with ostensibly Tatar or Jewish features—“Oriental barbarians,” in Nazi-speak.

Soviet newsreels from before the German assault show Kyiv as a normal city, albeit with startlingly contemporary images of citizens filling sandbags, uniformed nurses strolling through the streets, and children playing amid the antitank obstacles known as Czech hedgehogs. This paean to Soviet preparedness is more or less dissolved by a sequence in which Lviv celebrates its incorporation into a Nazified Poland. Loznitsa found, or fashioned, a mini Triumph of the Will: all martial anthems, parades, and solemn ceremonies bedecked with flowers and swastikas to the glory of Governor-General Hans Frank.

Advertisement

The Germans occupied Kyiv on September 19. The Soviets bombed the city five days later; this became the pretext for the Germans to exterminate the local Jews. The killings are signified by still color photographs of abandoned clothing and personal effects—reminiscent of, perhaps an inspiration for, the French artist Christian Boltanski’s Holocaust-haunted installations of bundled belongings—piled up around the ravine. The photos are shown near-silent, as are subsequent images documenting the round-up of Jews in the nearby town of Lubny.

These frozen moments are perhaps the most wrenching images in the film. German occupiers record bewildered children and helpless adults, all doomed, staring at the camera in mute accusation. Nothing is heard but the soft whistle of the wind. Then, scrolling down the screen in the film’s only substantial annotation, two paragraphs from Soviet war correspondent Vasily Grossman’s unbearably eloquent eulogy “Ukraine Without Jews.” His firsthand report of the aftermath of the Nazi massacres in Ukraine, written in 1943, made clear that the victim were Jews. Suppressed by Soviet censors, which downplayed the ethnic aspect of the killings, it was published in Yiddish and did not appear in Russian until 1990.

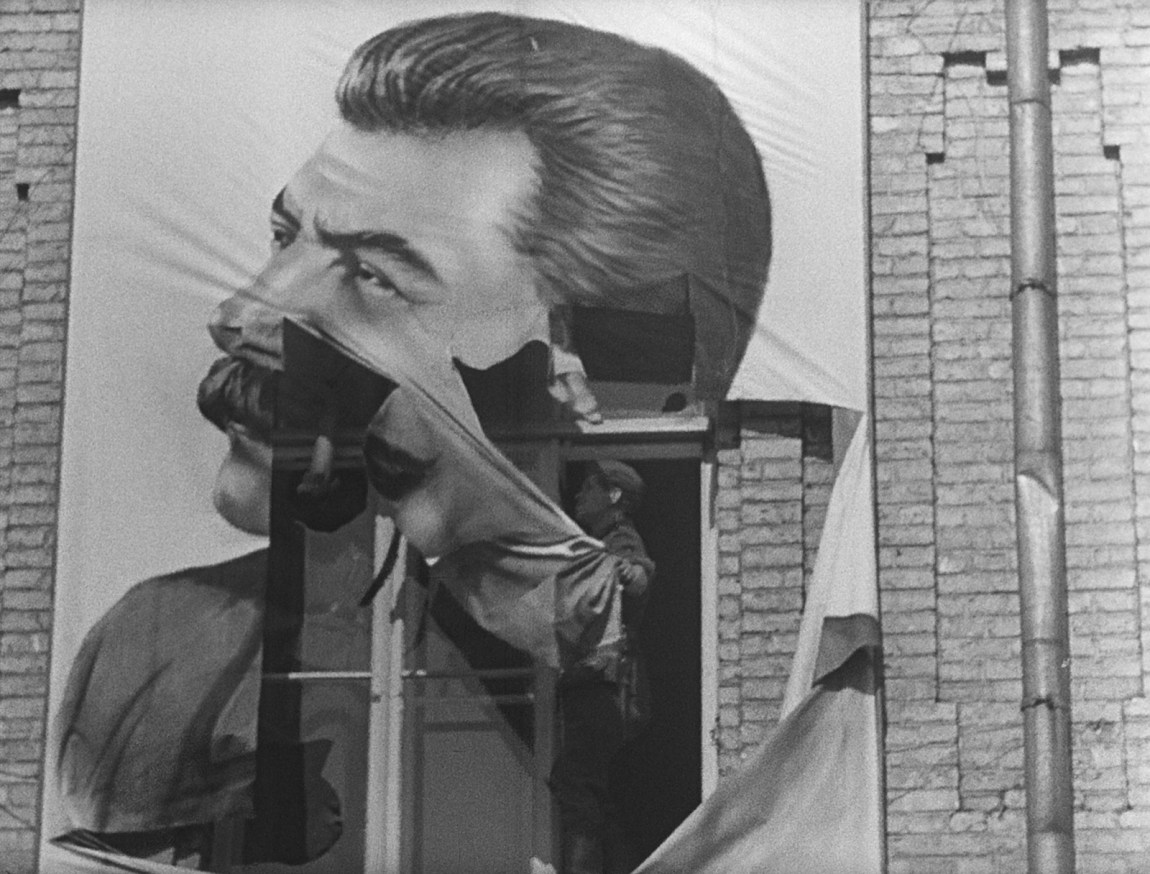

The Soviets retake Kyiv in the movie’s second half, and American journalists are led to the ravine at Babyn Yar to receive an account of the September 1941 massacre, and subsequent ones. (As per the official Soviet account, no victims are identified as Jews.) Soon after that, the Red Army liberates Lviv. German signs are knocked down, and images of Hitler are replaced with images of Stalin. No less a personage than Nikita Khrushchev, Ukraine’s former governor appointed by Stalin, appears to deliver a speech invoking the common Slav heritage of Poles, Ukrainians, and Russians, his address followed by a mad display of acrobatic kazatski dancing.

Some hearings into the 1941 massacre were filmed. Witnesses testify, notably the miraculous survivor Dina Pronicheva, a crucial witness for Anatoly Kuznetsov’s 1966 documentary novel Babi Yar—a literary event even more scandalous to the Soviet authorities than Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s 1960 poem on the subject. A German officer is put on trial and, while corpses are plentiful throughout the movie, his public execution together with a dozen other SS men is the only time an act of killing is actually shown.

In 1952, the Soviet authorities decided to bury Babyn Yar by filling the ravine with industrial waste. A decade later, a mudslide further submerged the site. Some color footage shows Babyn Yar as it is now, unrecognizable after earlier photographs have seared the original landscape into memory. Loznitsa does not show the various memorials, some more appropriate than others, that have since been created. The problem of what to do with Babyn Yar has never been resolved. Appointed as artistic director of the Babyn Yar Memorial Center in 2020, the Russian filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky planned a sort of scary, punitive theme park—a fate somewhat anticipated by Loznitsa’s 2016 documentary Austerlitz, in which a static camera, planted at several locations in a German concentration camp-turned-tourist attraction, observes bored school groups and dutiful sight-seers wandering about posing for selfies.

The effaced site that is Babyn Yar was bombed during the first days of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, when an airstrike hit a TV tower next to the park. Whether or not the memorial was an intentional target, the strike was only the latest display of Russia’s indifference to the actual victims and history of the Holocaust, which the state continues to exploit for its own ends. The impossibility of memorializing Babyn Yar is crucial to Loznitsa’s painful, provocative, sobering film. The abrupt black screen with which the movie ends suggests exactly this absence: a frame around a void.