Martin Vaughn-James was born amid the apocalypse and never recovered. As he said on more than one occasion, his birth in Bristol on December 5, 1943, occurred “during an air raid.” The visual landscape of his childhood, he wrote, consisted of “abandoned airfields, weed-covered bomb-sites, enigmatic bits of shell-casings, helmets, rusting away in woods and fields.” Like the slightly older J. G. Ballard, who was a child in a Japanese internment camp during the war, Vaughn-James acquired a taste for post-apocalyptic architecture: the depopulated and denatured concrete monuments that will survive even atomic desolation.

Vaughn-James had a varied career as a multimedia artist, working in forms as different as painting and novel writing—but his most important innovations came in a medium that combined pictures and words. In the 1970s he produced four pen and ink “visual-novels” notable for their cinematic phantasmagorical imagery and attentiveness to the possibilities of book binding, elevating the conventions of underground comics to an enduring and artisanal form. These four books—Elephant (1970), The Projector: A Visual Novel (1971), The Park (1972), and The Cage (1975) were far ahead of their time, and now stand as landmarks in the development of the graphic novel.

Vaughn-James’s family moved to Australia in 1958, where he studied art at the National Art School in Sydney and first came under the sway of Surrealism. In 1967 he married the poet Sarah McCoy and the two moved to Canada the following year, during a time of nationalist revival in the arts there. It was also a time of revival for the surrealist tradition, thanks to the marriage in the 1960s of psychedelic culture and radical politics, and Vaughn-James found a creative home for his experiments in graphic arts.

The original French surrealist school, most fruitfully developed in the theory and practice of André Breton in the 1920s and 1930s, was an outgrowth of Marxian attempts to develop an art that would subvert conventional ideas of consensual reality. As an exile from Vichy France, where his work was outlawed, Breton lived briefly in Canada in 1944 and influenced a host of Canadian creators, both in the visual arts (for example Les Automatistes, which emerged in Montreal in the early 1940s) and literature (notably poets such as Leonard Cohen, bpNichol, and Michael Ondaatje).

The Situationist International, among others, tapped into this aspect of Surrealism during the insurrections of the 1960s, repurposing surrealist mockery of media culture in vernacular forms that could reach a radicalized urban audience through graffiti, slogans, leaflets, and posters. Vaughn-James’s early artistic statements often echo Breton as well as the Situationists. In Canadian Forum in 1970 he wrote,

The modern world is a fantasy; a fantasy of our reason, our logic, our insistence on problems and solutions. Elephant is a man living subjectively, illogically and mysteriously. Elephant is a confused whimper in a corridor of steam-irons and bank buildings. Elephant is a heart in a cardboard box, its beat almost inaudible as it stands in an empty parking-lot.

He added: “ART IS ANARCHY OF THE SPIRIT.”

There are many paths to anarchic surrealism. One of them is through comics. In Australia, Vaughn-James had started reading Mad magazine, “with its marvelously anarchic satires and astonishing draftsmanship.” Prior to that he read comics of the “staid, old-fashioned English variety, quite different from their fantastic, hyperactive American counterparts.”

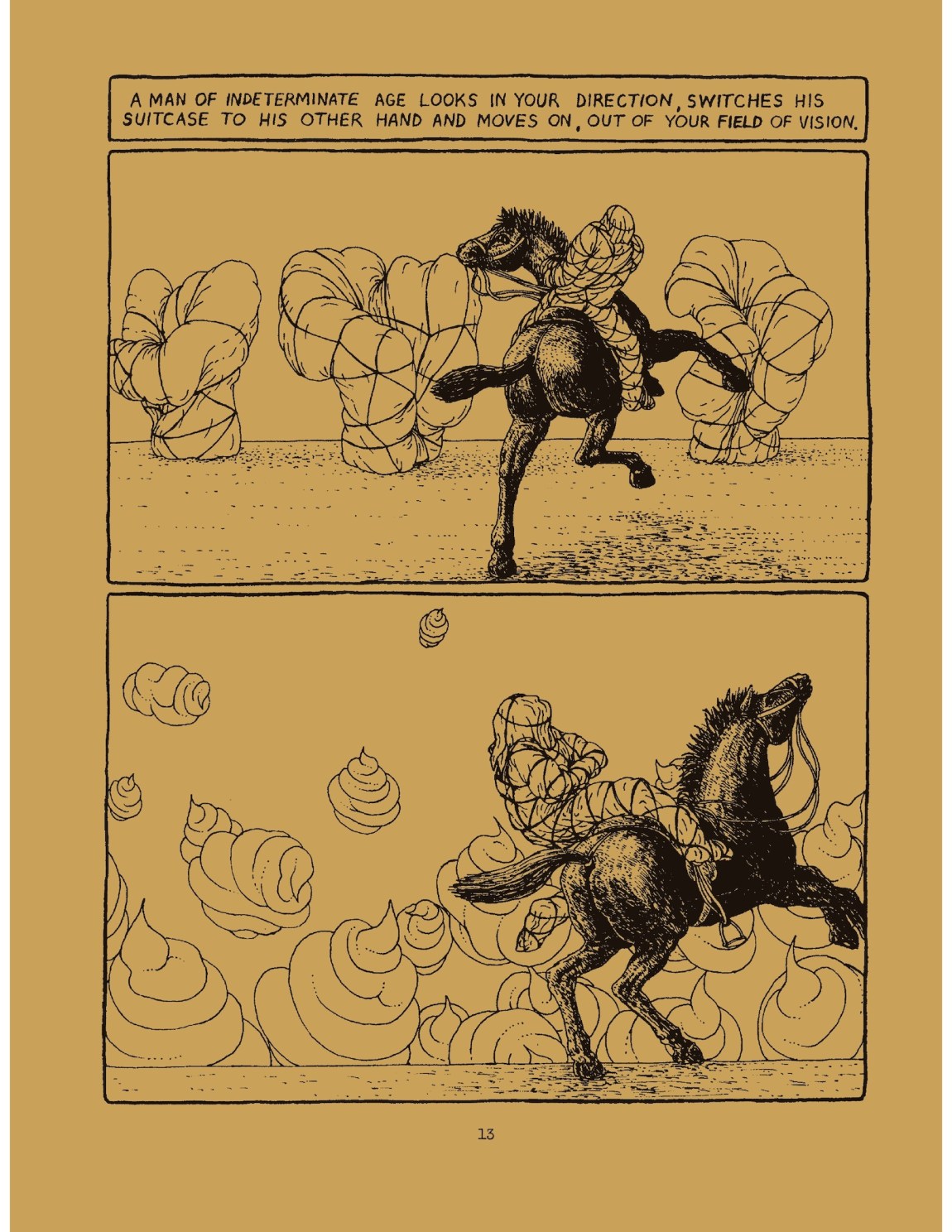

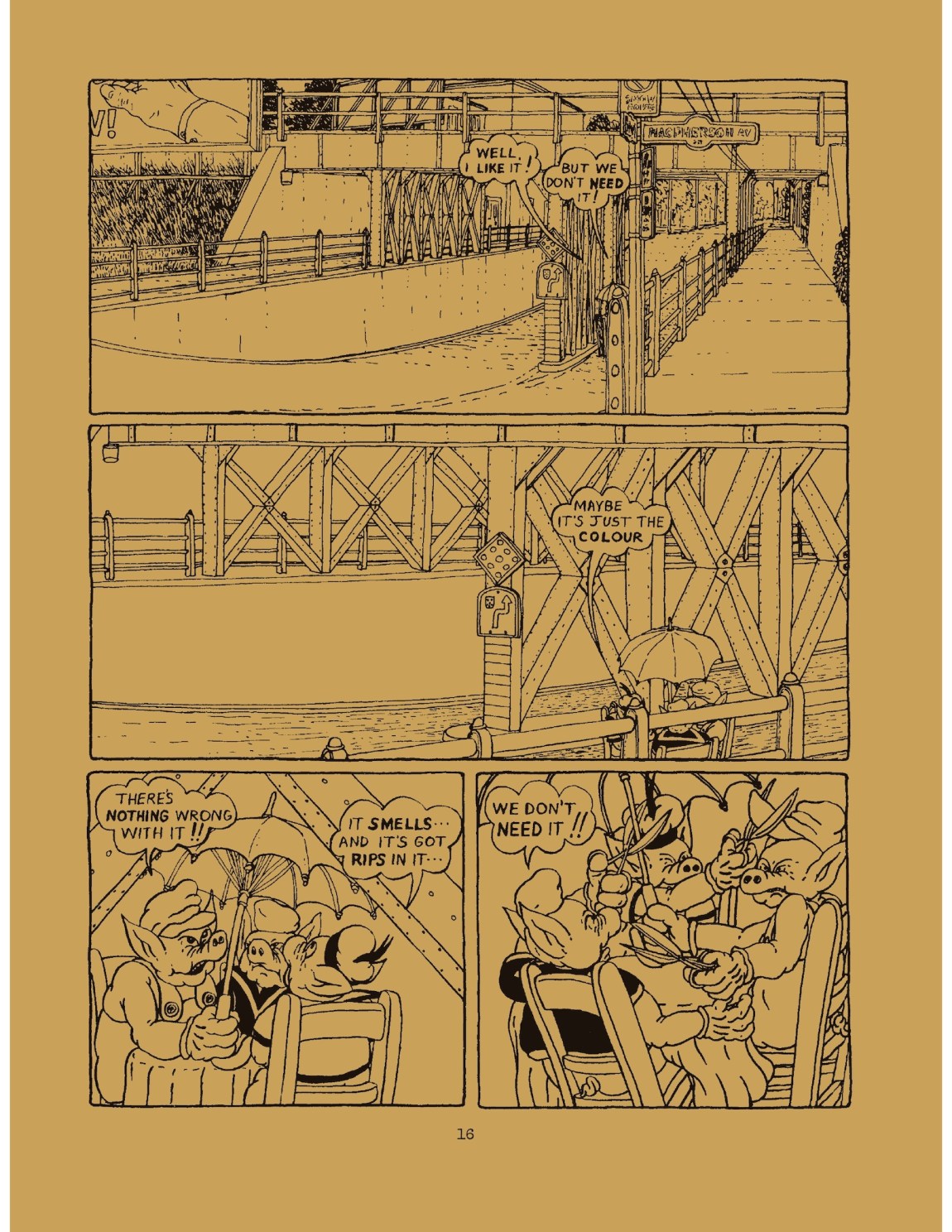

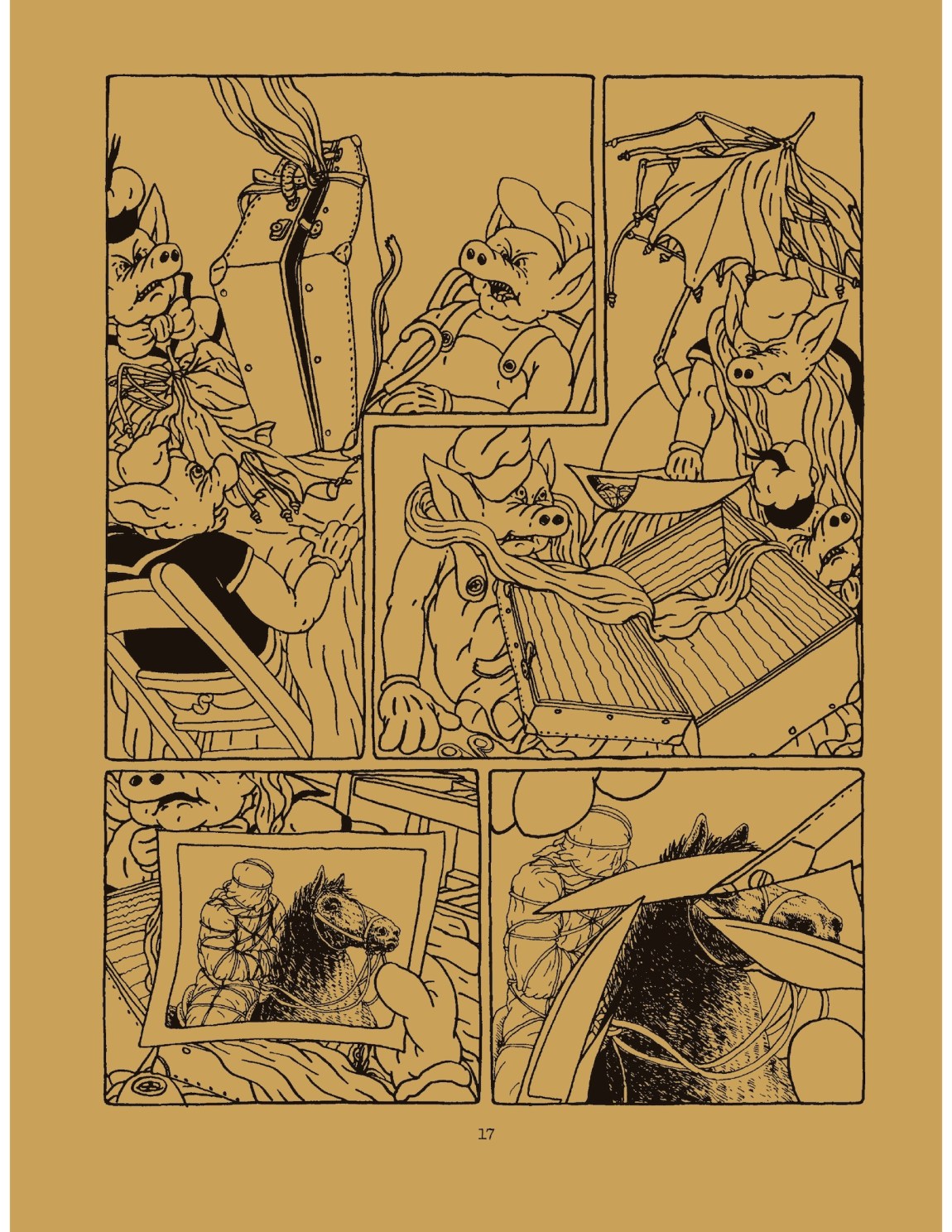

He only alludes to the American underground comics in passing, but they clearly had a strong influence. Many of the early reviewers of The Projector drew comparisons between it and the works of Robert Crumb as well as the psychedelic artist Victor Moscoso and the underground cartoonist Vaughn Bodē. The anthropomorphic characters in The Projector (a sinister incarnation of the Three Little Pigs, various dog-men) are all Disney characters gone to seed, a style Crumb pioneered. Even the gait of Vaughn-James characters—the way the nailed bottoms of their shoes are visible—calls to mind Crumb’s signature “Keep on Truckin’” slouch.

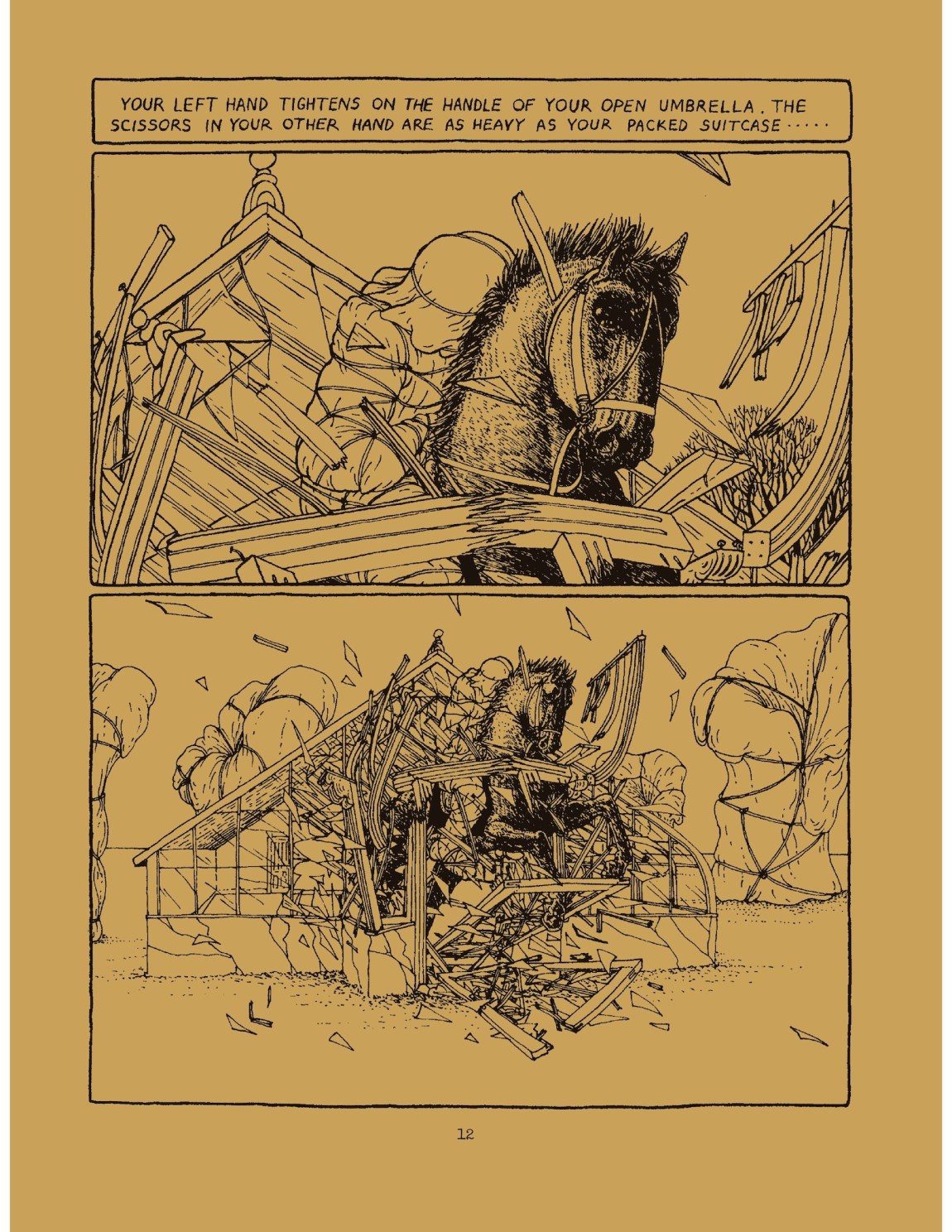

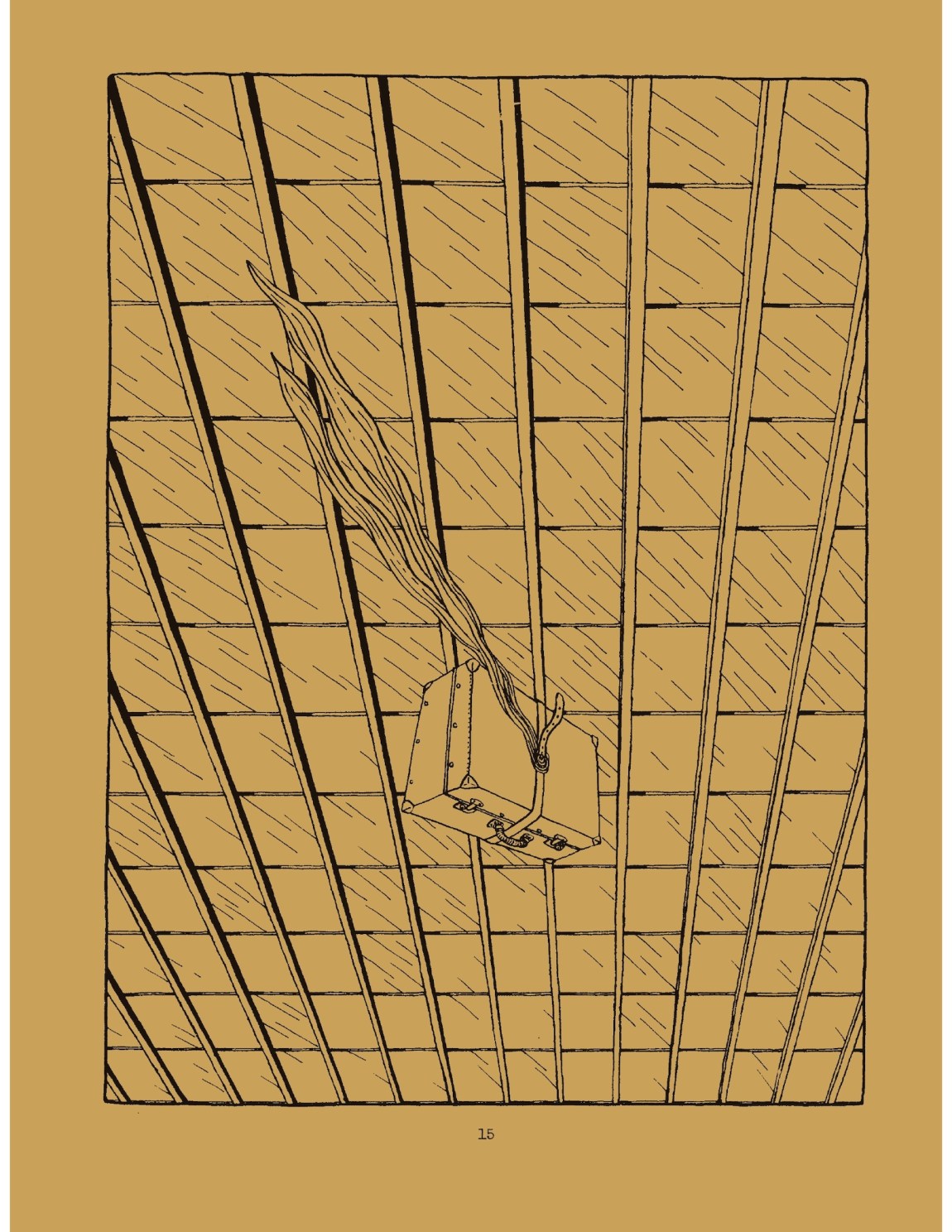

But if Vaughn-James was a fellow traveler of American underground comics, his work was more ambitious than anything the undergrounds were doing in 1970 or 1971. This ambition was evident in the length of his narratives and in his systematic mining of Surrealist iconography. Another crucial distinction is that, whereas the underground cartoonists were mainly interested in subverting the most pervasive cartoon icons of popular culture (in the Air Pirates Funnies, Disney characters performed X-rated acts), the consensus reality Vaughn-James was more interested in exploring and questioning was mechanical and architectural. His true subject was the urban, technological life-world, commanding but mute.

He was, finally, distinguished from his underground contemporaries by his interest in the bound book as a form. Elephant and The Park were stapled chapbooks rather than bound volumes. Elephant was roughly the size of a magazine (8 1⁄2 by 11 inches) while The Park was closer to the dimensions of a pamphlet (or what a later generation would call a mini-comic or a zine). The Projector and The Cage were, by contrast, books that announced themselves as books, printed on heavy matted paper and assembled by Coach House Press, a small publisher at the forefront of artisanal bookmaking in Canada. Vaughn-James’s process was to try out a storytelling gambit first in a chapbook and then dive into it at greater length in a book, taking unusual care in selecting sumptuous paper stock, trim size, and binding. Elephant was a dry run for the stream-of-consciousness flow of The Projector, just as The Park laid the groundwork for the juxtaposition of still-life images with elliptical narration in The Cage.

Advertisement

The Projector (1971)

Artists always outrun the preexisting critical vocabulary. Vaughn-James was making graphic novels with a degree of purpose and forethought perhaps unique in North American cartooning of that era, but it’s unlikely he had heard of the graphic novel before he had moved on from the form. The term was coined in 1964 by the comics fan Richard Kyle, and was later picked up and popularized by the cartoonist Will Eisner, who used it to describe his own long-form comics narrative, starting with A Contract with God (1978).

Vaughn-James was almost certainly unaware of Kyle, and he predated Eisner. So instead of calling himself a graphic novelist, he (or his publisher) conjured up the gawky neologism “boovie” (“book” plus “movie”) to describe Elephant. Explaining the new form in Canadian Forum, Vaughn-James wrote:

It is not a book, not a comic-strip, not a de-animated cartoon, not a scenario for a film. It is a new form, which, granted, like any new form owes something to those already in existence. The Boovie is primarily a visual experience. The book has been transformed into an object in its own right.

Thankfully, Vaughn-James quickly gave up the term and settled on the simpler “visual-novel.” As his Canadian Forum comment makes clear, he was proud of the innovative nature of the form he was experimenting with but also aware that it “owed something” to earlier work. He was chary, however, of spelling out these influences. He was a Francophile, and the two sources he cited most consistently were Surrealism and the nouveau roman of Alain Robbe-Grillet and other writers (evident in the foregrounding of objects and downgrading of events in The Park and The Cage). Beyond these movements, Vaughn-James saw the visual-novel as part of the longer history of book-form visual storytelling. As he told Canadian Fiction magazine in 1982:

I suppose the [drawn strip] has altered the history of the book in some measure over the last few decades and my small contribution could be tacked on to the end of that if you like, and of course it carries echoes of the past, reviving some aspects of the great days of the 19th century illustrated books.

One way to understand Vaughn-James’s isolated status is to realize that the graphic novel is itself a kind of phoenix art form: it’s had not one birth but many. It was invented time and again by lone-wolf artists who saw the potential of fusing sequential images with text. As more and more proto–graphic novels are brought back into print, we can track the phoenix through two centuries: the nineteenth-century drawn narratives of Rodolphe Töpffer and Caran d’Ache, the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward and others, and the “picture novel” It Rhymes with Lust made in 1950 by Arnold Drake, Leslie Waller, and Matt Barker, as well as sundry one-off experiments like Citizen 13660, a 1946 tale of Japanese-American internment by Miné Okubo. Each invention flourished briefly and was forgotten, leaving the graphic novel to be reinvented anew.

One reason the graphic novel experiments of the 1970s had a hard time gaining a cultural foothold was that there was no secure market or distribution network for them. Underground comics were sold through head shops that were constant targets for police harassment, and the direct market of comic book stores was only fledgling. The major critical work of The Comics Journal, under the editorship of Gary Groth, in promoting the graphic novel only started in 1976, after Vaughn-James had completed his work in comics; the intellectual project of the Journal wouldn’t coalesce until the 1980s, when Art Spiegelman’s Maus and the serialized narratives in Love and Rockets by Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez provided grist for the critical mill.

Oriented as he was toward France, where he eventually moved in 1978, Vaughn-James kept his distance from Canadian nationalism, although he was always quick to express gratitude for the personal and institutional support he received from Coach House Press, the Canada Council, and the Art Gallery of Ontario (which put on a major show of his work in 1975). Despite his own disavowals, there are affinities between his work and that of other Canadian creators. As the critic Sean Rogers notes, Coach House “was home to kindred spirits,” writers, including Ondaatje, bpNichol, and Steve McCaffery, who championed Vaughn-James’s work. Ondaatje wrote a poem about The Projector for his 1973 collection Rat Jelly:

Advertisement

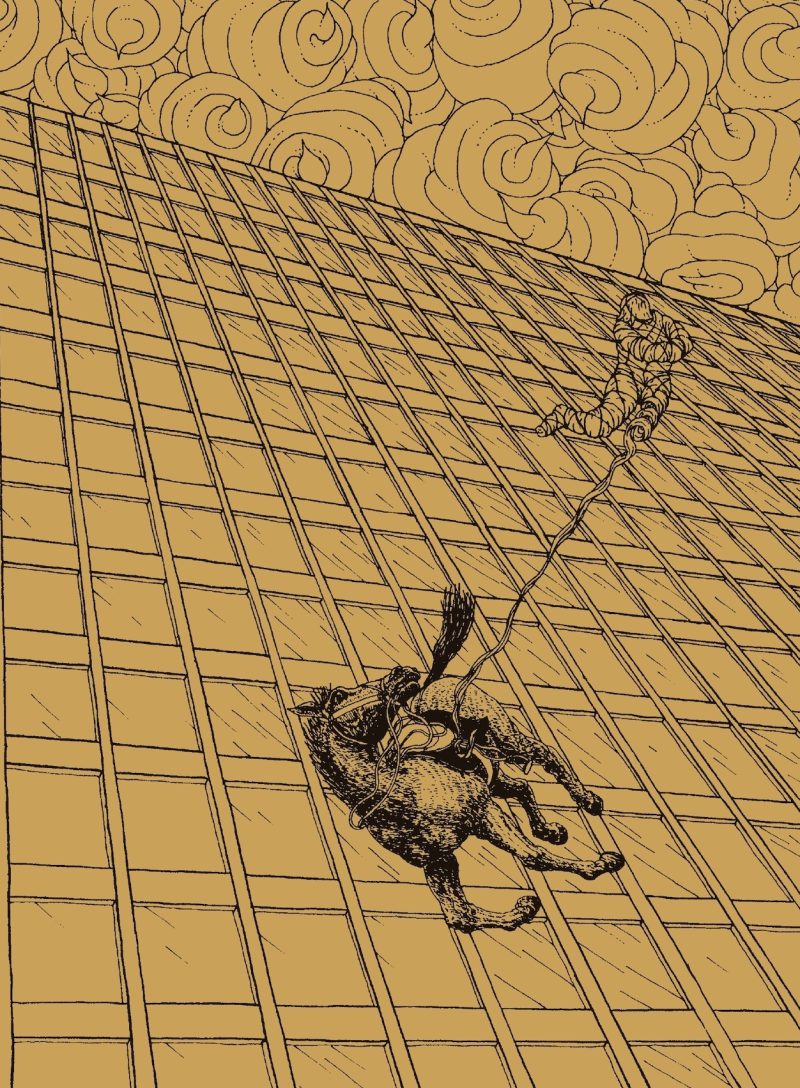

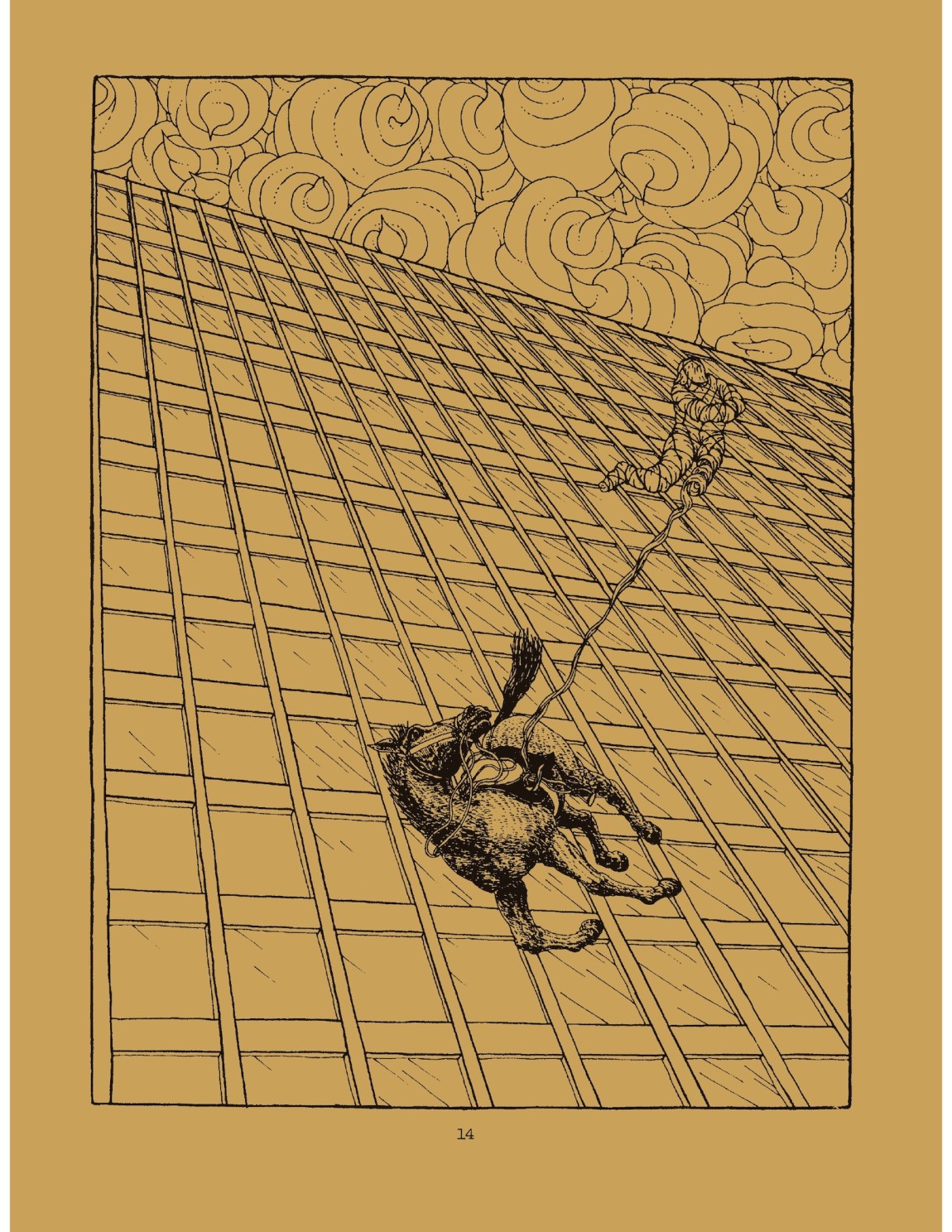

The horse is falling off a skyscraper

staggering through the air.

He will never reach

pavements of men and cars,

he is caught between

the 70th and 72nd floor of someone’s brain.

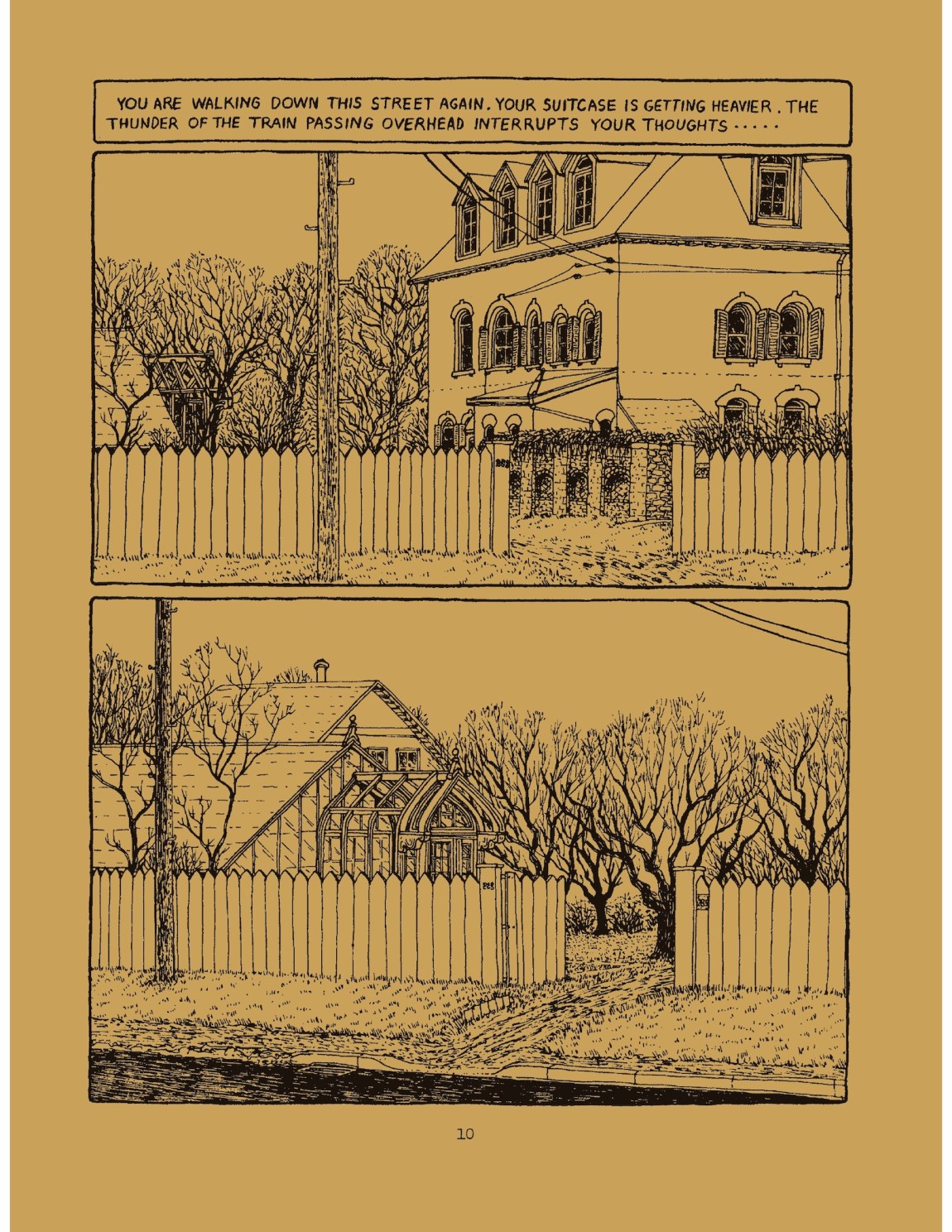

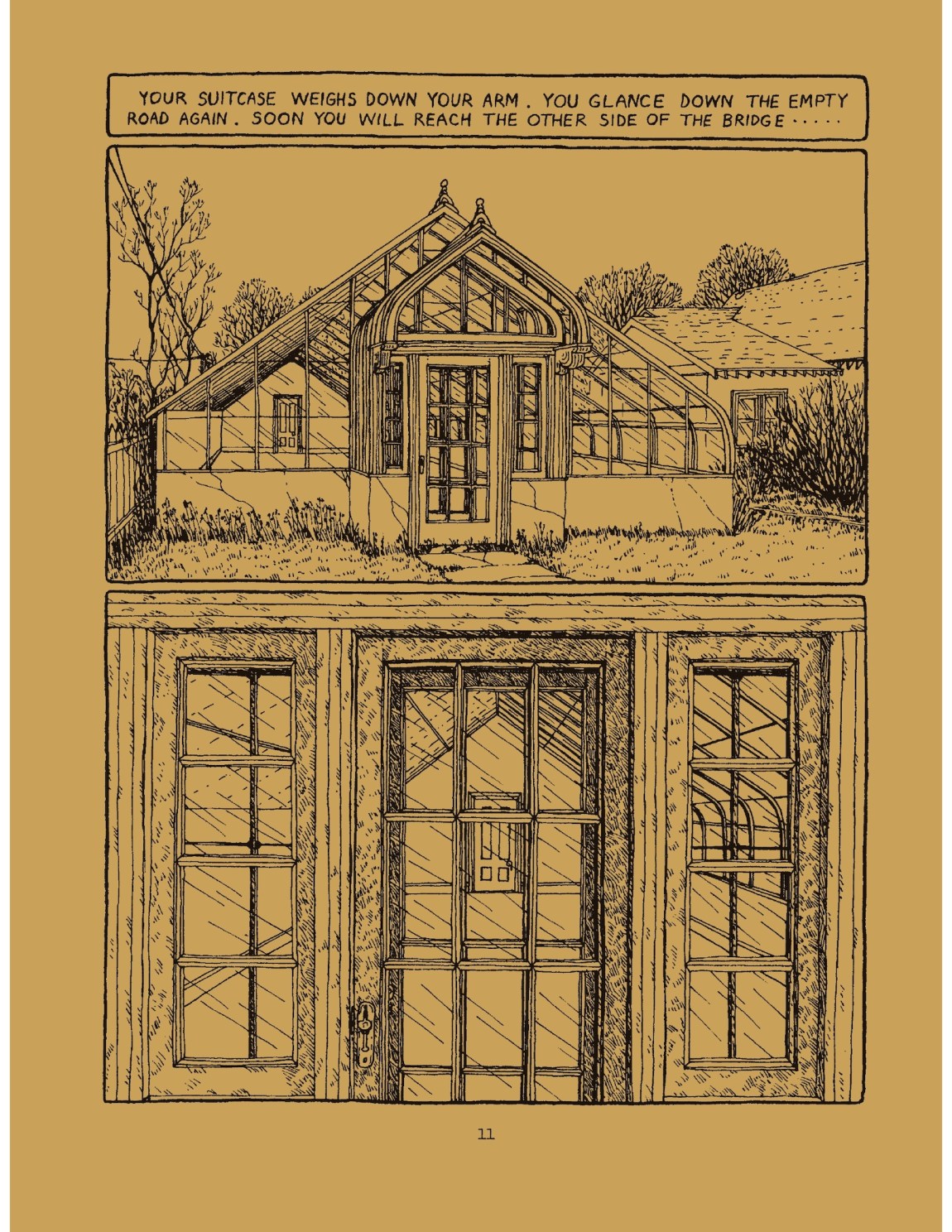

Rogers has also called attention to the felt presence of the built landscape of Toronto in Vaughn-James’s graphic novels of the 1970s. Spadina House, a historical museum with a greenhouse in downtown Toronto, appears in The Projector, and other nearby landmarks figure in subsequent works—a persistent foray into psychogeography that is another important overlap with the Situationists.

In his early essays Vaughn-James often adopted the bravado of a manifesto writer. Later in life he was more modest but still confident about the importance of his experiments. Asked about the limits of the visual-novel, he responded: “Limits? I don’t think so. The possibilities of the form seem very large to me. There are a lot more things still to be done.”