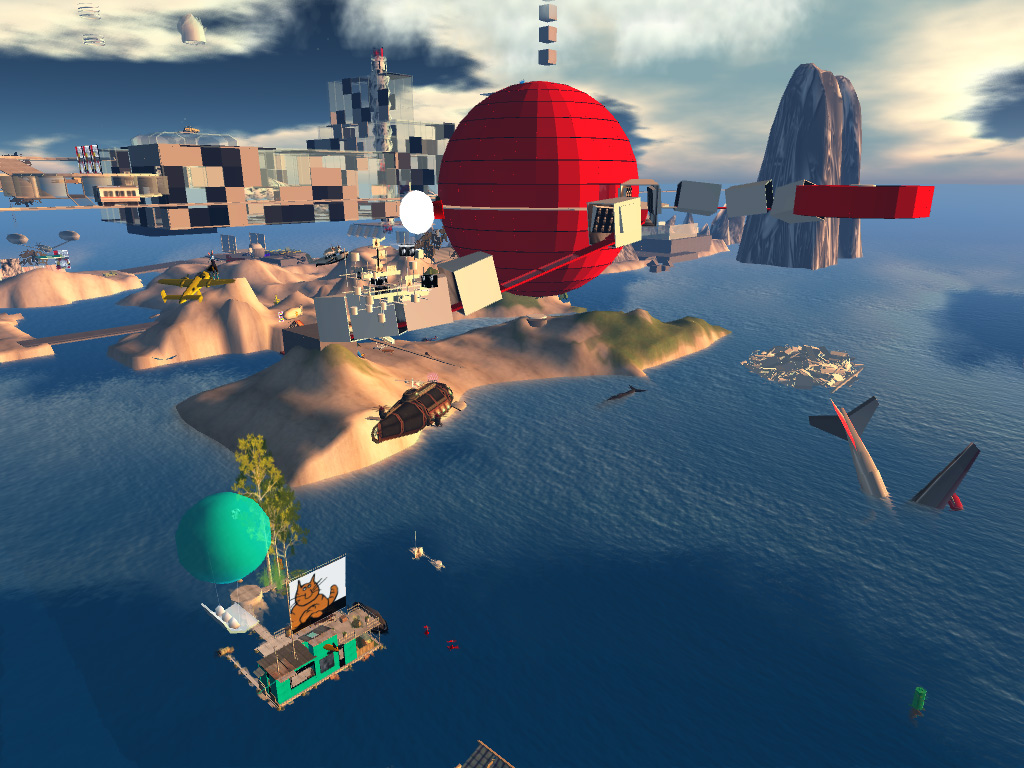

“Yes, you can fly,” said one of the moderators. “We’ll be doing that in a minute.” There was scattered laughter in the theater of the Harvard Film Archive, where what appeared to be a role-playing video game was projected on the screen behind a live panel. As the panelists moved their avatars around the setting, a cluster of islands in a digital sea, the audience took in a line of cat-headed moai, a floating red globe, and a beached whale that punctuated every few minutes with a dolorous whoop. It was May, 2009, and the online platform Second Life was in its heyday.

One of the event’s organizers mentioned that other users might drop in, and sure enough, they soon found themselves jostling for space among a mob of avatars: strangers with parrots on their shoulders, trailing fluorescent veils and sporting green skin. Word had evidently gotten around that Chris Marker was due to put in an appearance.

In the last decade of his life, the French filmmaker became an avid user of Second Life, where he went by the name Sergei Murasaki, maintained an archipelago known as Ouvroir (“workroom”), and built a virtual museum in collaboration with the Austrian architect Max Moswitzer (alias MosMax Hax on Second Life, where he often appeared as a muscular white lion with a spiked mane). Touring the digital space with Marker himself, then eighty-eight, was supposed to be the aim of the Harvard event, a rare interview from a director normally known for his reclusiveness. But when it came time to start, Haden Guest, the director of the HFA, couldn’t figure out how to get his avatar to stop dancing along to the boisterous jazz music that someone was playing in the background. It took a patiently typed intervention from Marker-Murasaki for Guest to wrangle his limbs back under control so that the discussion could begin.

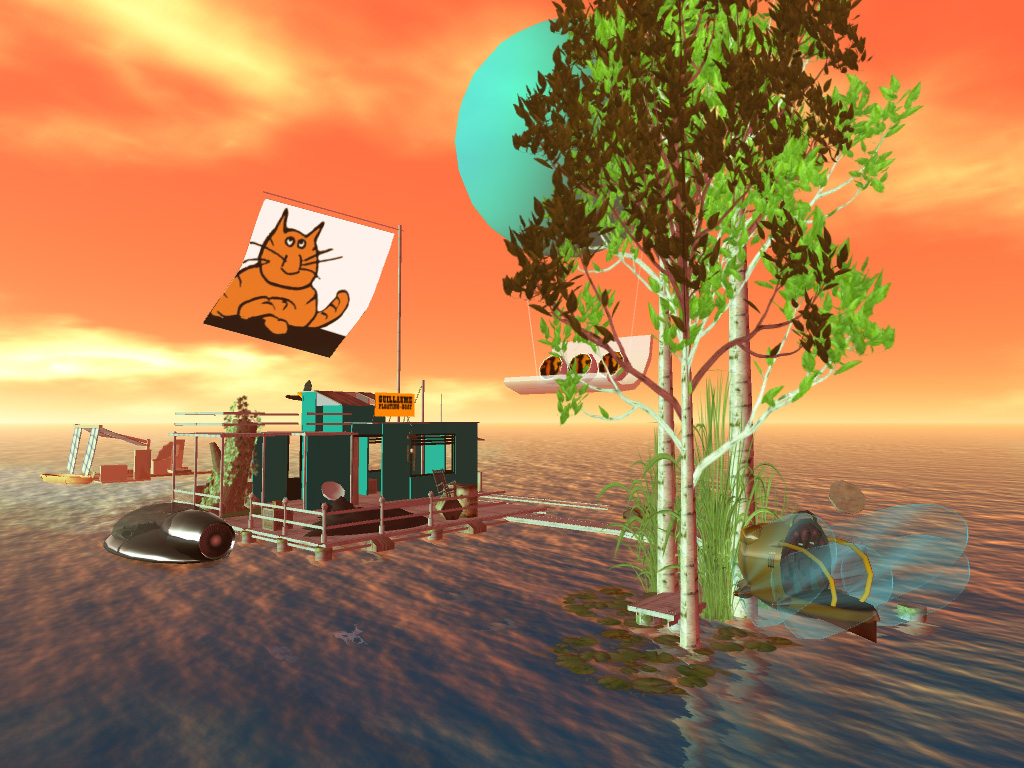

Marker spent much of his career avoiding media attention, preferring to hide behind his feline alter ego, Guillaume-en-Égypte. When journalists requested photos, he’d send them pictures of his cat; when Agnès Varda filmed the two of them strolling down a street in Paris for a TV show in 2011, he trundled along a Guillaume effigy on a dolly to shield himself from view. (Marker also frequently used Guillaume as an avatar on Second Life, where the platform’s graphics rendered the creature’s body as a series of orange dinner rolls.) An exhibition devoted to Marker in Brussels could turn up only a single photograph as evidence that the director had at one point been married. “Chris Marker” was a pseudonym, and for years he swapped even that for the anonymity of the collective to produce collaborative works like those he undertook with workers in eastern France under the banner of the Medvedkin Group. “This legendary denial,” reads a textbox at the entrance to Marker’s museum in Second Life (visible when you touch the belly of a Guillaume-shaped sign), “would suggest that he was destined to become an avatar.”

In contrast to the herky-jerky movements of his interviewers, Marker seemed perfectly at ease in Second Life. He navigated the world and its keyboard commands smoothly, like a native, and appeared to be on friendly terms with many of the people thronging the island. For the HFA event, he’d even chosen to take a human form, appearing as a bald, olive-skinned man in cuffed jeans and a white tee. Compared to the riotous looks of those around him, he seemed almost underdressed. More to the point, aside from its body-builder physique, his avatar bore a passing resemblance to its maker. In place of his usual puckish refusal to disclose himself, there was a new openness and ease. “It is so easy to lie that I am sure some derive a perverse pleasure from saying the plain truth,” Marker mused via chat box, as a parade of oversized floating cans plowed into his avatar and bounced off.

*

Second Life was launched in 2003 by Linden Labs, the creation of a programmer named Philip Rosedale whose vision for the project was influenced by his days among the ecstatic crowds at Burning Man. With an interface that encouraged users to design their own content, Second Life garnered a reputation as a place where one’s wildest fantasies could become, if not real, at least a laggy approximation. Users may inhabit the world in a variety of customizable forms: as a banana, a mall Santa, a human-goat hybrid, a hand that “walks” on two fingers. These avatars can joust, reenact life in eighteenth-century Italy, or teleport to a moonbase. For all these features, what continue to draw people to Second Life are the bonds they can form there. Many of the platform’s most popular destinations are the sorts of venues that already exist in the real world: cafés and clubs, places where you can meet people and make friends. At Second Life’s peak in the late 2000s, when it had over a million active users, multiple countries were operating digital embassies there. Users tend to reject the term “game”: Second Life, they insist, is a world.

Advertisement

By Marker’s account, he quickly grew to find the platform “addictive.” During an interview conducted on the platform for the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles (later translated into English for the Criterion Collection), he declared that if it were possible he’d retire there forever, “like Brando in Tahiti.” The virtual archipelago he and Moswitzer built took full advantage of the platform’s otherwordly physics. The museum’s main building is shaped like Saturn and floats in the air above the sea; the approach is made via a narrow ramp flanked by walls upon which T. S. Eliot’s poem “The Hollow Men” is projected. Cats are everywhere: paving the museum floor, adorning the exterior of a submarine, even taking the form of a great mountain crowned with Guillaume’s head.

What first drew Marker to Second Life? In the Inrockuptibles interview, he described the platform as “a dream state” that evoked “the sense of porousness between the real and the virtual.” His films tend to depict video games not as amusements or means of escaping from real life but as entities capable of acting upon and even against the external world. Level Five (1997) follows a woman whose game-developer lover has recently died while working on a simulation of the Battle of Okinawa. As she explores her lover’s final creation and attempts to rewrite its ending, the computer refuses and resists; there are things it cannot or will not do. In Marker’s work, virtual worlds are “dreamlike” not in the sense of being wonderful but because upon entering them we are not fully in control, in thrall to forces we do not necessarily recognize or understand.

Navigating Second Life is indeed an uncanny experience. Objects only appear in your field of view once you’re suitably close, so that landscapes that seem from a distance to be undifferentiated fields of scrag grass reveal themselves to be teeming with buildings and beings that pop into existence as you walk. The effect is enhanced when too many people are in the same space, slowing the flow of digital reality. Like a land before object permanence, the platform’s terrain is constantly forgetting and remembering what it contains, provided there is someone there to remind it.

Second Life challenged Marker to create meaning in a world without history, a striking departure for a filmmaker who had long dwelled on the relationship between the present and the past. Often taking the form of a brocade of media—stock footage, animation, video game clips, shadow puppetry—his film essays uncover surprising linkages and breaks between one time or space and another. The montage in Sunday in Peking (1956) allows Marker to convey both the continuities and disjunctures between pre- and post-revolutionary China. His taste for strange combinations and otherworldly effects—as when, in Junkopia (1981), shots of driftwood sculptures are set to eerie electronic wails, making them appear like the jetsam of an alien civilization—would later define his Second Life archipelago. The degree of manipulation inherent in such techniques is something Marker skewers openly in Letter from Siberia (1957) by presenting the same footage of a Yakutsk street again and again, each time with a different voiceover to interpret what we are seeing.

In his films, Marker maintained a distance between himself and viewers, often through layers of retrospection. La Jetée (1962), which chronicles a post-apocalyptic civilization’s attempts to travel back to a past before disaster, viewers are shown not the action as it unfolds but its reconstruction after the fact, as told through a series of still photographs. The narration of his best-known work, Sans Soleil (1983), consists of letters written by Marker pseudonymously, and it is someone else who reads them and relays to us the stories of his travels and his thoughts. Though viewers follow in his footsteps, we are left with the impression that we will never catch up.

Marker viewed attempts at exhaustive archiving—whether in the card catalog of a national library or on a computer server—with a certain degree of skepticism. In Toute la mémoire du monde (1956), a short documentary on the Bibliothèque Nationale made in collaboration with Alain Resnais, the institution’s mission of recording all human endeavor is to be both admired and feared: the library is figured at once as a fortress that imprisons all it contains and as a monster that consumes everything it comes across. When in Sans Soleil Marker’s friend uses digital effects to imagine what the film will look like when covered over with what he calls “the moss of time,” the images are fuzzy and difficult to read but also strangely beautiful, alive with riotous color.

Advertisement

Remembering, Marker’s alter ego says elsewhere in the same film, “is not the opposite of forgetting but rather its lining. We do not remember, we rewrite memory much as history is rewritten.” The psychonauts forced to go back in time through their memories in La Jetée must do so with their eyes covered; there can be no knowledge without a certain blindness. Marker did not lament the vagaries of memory but celebrated and exploited them for all their poetic, impish potential. Careful viewers of Toute la mémoire du monde will notice that the book whose entry into the library’s system the film follows is a travelogue of Mars—a fake installment of the “Petite Planète” series Marker edited, a lie that manages to worm its way into the heart of Truth.

Moswitzer’s museum, which takes as its subject Marker’s own personal history, would seem to risk becoming precisely what the filmmaker’s work poked fun at: a totalizing archive. But even here Marker achieved a degree of détournement. One area, for instance, is dedicated to posters of “premakes,” iconic films reimagined as products of Hollywood’s Golden Age. There’s an ad for Rambo Minus One and another for a version of Hiroshima Mon Amour shot two decades before the city was leveled. “Once in a while,” Marker wrote, in an intertitle for his 2009 film Ouvroir, “someone in the audience screams ‘I remember… I saw this movie long ago!’ Makes my day.”

“The things that are born are due to end, aren’t they?” he said to the crowd at HFA when asked about the ultimate fate of his museum, which had recently been threatened with deletion. (The Centre Pompidou stepped in at the last minute with the funds to renew its lease.) Impermanence was built into the space itself: we move through the different stories in Marker’s museum not by taking the stairs but because, without warning, the floor beneath us collapses.

*

Poptronics, a French publication devoted to hacktivism and internet culture, called Marker “the first geek.” His studio was a rat’s nest of wires with clusters of monitors that beamed dueling video streams at one another; he had a soft spot for digital effects that were dated even at the time he used them and generally rejected professional software in favor of exploring the possibilities of consumer-level tech. (The audio for Sans Soleil, for example, was all done on a simple portable tape recorder.) Marker was preoccupied with “the petty cash of history,” ephemera both analog and digital, bits and scraps that anyone could take up and use.

In the 1980s, he spent years working on DIALECTOR, a conversation bot he coded in Applesoft Basic and stored on floppy disks. There were rudimentary plans for interactive elements and something akin to touchscreen capacity. But the ambitious project was shelved in 1988, when, as Marker put it, “Apple decided that programming should be reserved for professionals.” Tech was increasingly moving away from the proletarian, hacker spirit that had drawn him to coding in the first place. Second Life, with its sometimes muddy graphics that bespoke the homemade origins of many of the world’s objects and places, seems to have struck Marker as a way to keep that spirit alive. He had long insisted that his craft was bricolage—do-it-yourself work, cobbling something together. The platform was an extension of this impulse, indeed its fullest flowering: it was, he called it, “supercobbling.”

One gets the sense that part of what attracted Marker to Second Life was the illusion of propertylessness it afforded. “I’ve never been the owner of anything,” he told Les Inrockuptibles—though his workspace was hardly sparsely furnished. In Poptronics, someone called Lucien Bookmite recalls running into Marker while exploring Ouvroir. When Bookmite rather coyly asked the director who owned that corner of Second Life, Marker played dumb. “The cat Guillaume thinks it’s his, as with everything,” he said. “He’s the biggest feline social climber on the planet.” When the HFA moderators asked him about the platform’s commercial aspects, he dodged again: “Frankly, I never approach the business side of Second Life. All I know is that a Chinese woman became a millionaire.”

The Chinese woman to whom he was referring is Ailin Graef, better known by her online moniker Anshe Chung. Dubbed “the Rockefeller of Second Life,” Graef became famous in the mid-2000s as the platform’s main landlord, dominating the market for quick currency exchanges between Linden Dollars (the platform’s in-game currency) and real-world money. At its peak, her Second Life real estate company employed dozens of people, with the most luxurious properties going for $1,000 in real currency, not to mention monthly fees. “Some day the entire affair could come crashing down,” one commentator wrote in an article about Graef’s riches from 2011. “Imagine if people suddenly lose interest in a simulated environment because a new and better one arrives. Your investments could turn out to be worthless.” Indeed.

If the sums involved in Graef’s story may seem quaint given the multi-million-dollar asking prices that NFTs command, her business empire nevertheless set the stage for the resurgence of the metaverse concept today: stratified, commercialized, and heavily enmeshed with surveillance, data collection, and engines of environmental destruction like cryptocurrency. It didn’t take long for corporations to start trying to muscle their way into Second Life: The Verge reported that Adidas dropped a million dollars for a virtual sneaker store, only for the shoes to be so poorly rendered that they caused the world around them to lag.

For all that he avoided talking about the capitalist side of Second Life, Marker was, at least earlier in his career, a dedicated communist with clear views about how the economy worked and how it should be structured. It’s therefore a bit disappointing that he had nothing to say about the flows of power and cash in the virtual world in which he spent so much time. In the intervening years, much of what Marker admired and even romanticized about the Internet has been steadily eroded. The widely panned, Wii Sports-esque graphics of Mark Zuckerberg’s proposed metaverse speak not, as Second Life’s crunchier parts sometimes do, to a spirited amateurism—to supercobbling—but to a lack of imagination and artistry. When Marker made Sans Soleil, he used digital effects to simulate the moss of time; now the digital has become more firmly associated by privacy advocates with both the all-seeing and the never-forgetting, the kind of indiscriminate archive of which Marker was so skeptical.

I first learned of Ouvroir years after its creation. By the time I watched the Harvard Film Archive interview, a recording of which had been uploaded to YouTube, almost a decade had passed since Marker’s death. But these pieces of him lived on, accessible to anyone anywhere, digital fragments embedded in the world like shrapnel in flesh. Even DIALECTOR, the conversation bot that he’d long ago given up on, had been resurrected by a group of artists in 2015. Upon booting it up, users are greeted with the comfort of familiar Markerisms: an owl’s fixed gaze, a few bars of eight-bit Mussorgsky. The program’s second line of code reads “THE SECOND SELF.”

It’s a tempting promise of authenticity from an artist whose career offers a long string of evasions. And yet Marker’s ability to lull visitors to his digital worlds into thinking that they were at last glimpsing something of “the real him” was one last trick—proof that he was, indeed, “destined to become an avatar.”

Toward the end of their tour the moderators, standing near an elephant on the shores of one of Ouvroir’s islands, asked Marker what he saw for the future of Second Life. He took a long time typing his response: “Imagine that we managed to program [our avatars] with all our memories,” he said. “We will leave them behind like ghosts. And after a while nobody could tell if the avatar he is speaking with is dead or alive.”