In his final story, “Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk,” Franz Kafka weighs the difference between making art and messing around:

So is it singing at all? Is it not perhaps just a piping? And piping is something we all know about, it is the real artistic accomplishment of our people, or rather no mere accomplishment but a characteristic expression of our life. We all pipe, but of course no one dreams of making out that our piping is an art, we pipe without thinking of it, indeed without noticing it, and there are even many among us who are quite unaware that piping is one of our characteristics. So if it were true that Josephine does not sing but only pipes and perhaps, as it seems to me at least, hardly rises above the level of our usual piping…that would merely clear the ground for the real riddle which needs solving, the enormous influence she has.

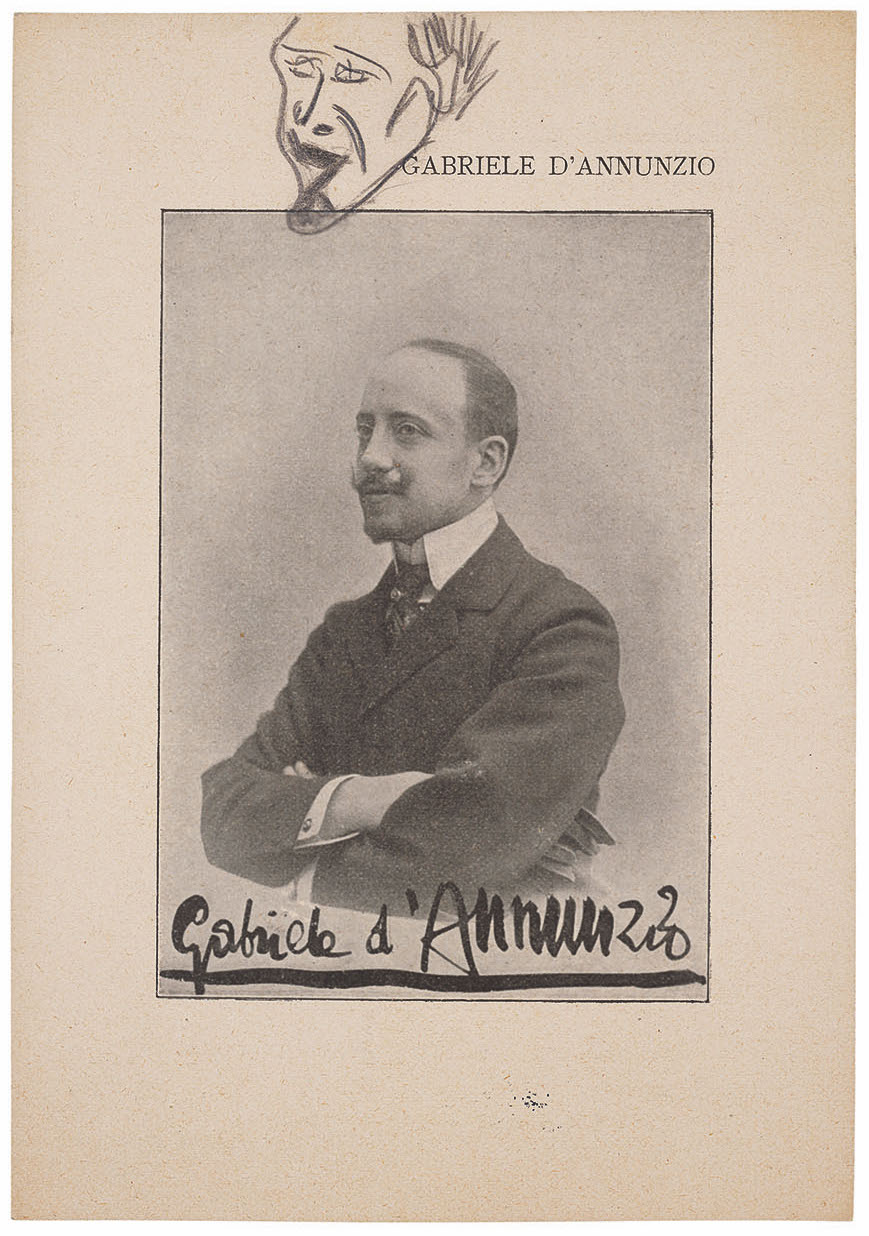

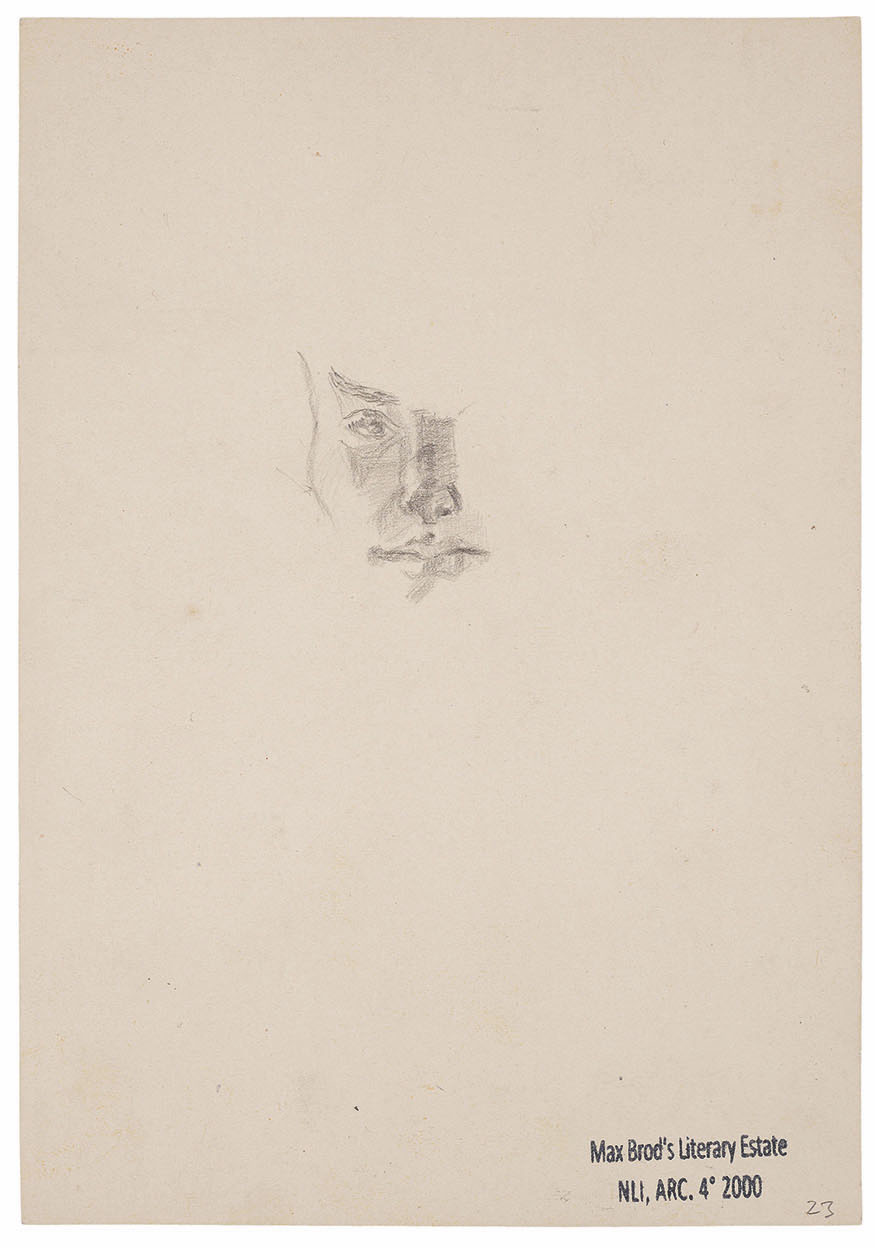

The question is whether virtuosity might be conveyed in a little whistle, and how to account for the prestige of a vaunted talent if anyone can do it. But does it change our reading to know that on the back of the story’s manuscript Kafka scribbled the leering face of a woman, possibly that of his lover Dora Diamant, the Polish émigré in whose arms he died of tuberculosis in 1924? Could it not be that, upon finishing the story, Kafka found himself wondering what it was all for—and, turning the pages face-down on the desk, absentmindedly doodled an answer to his question?

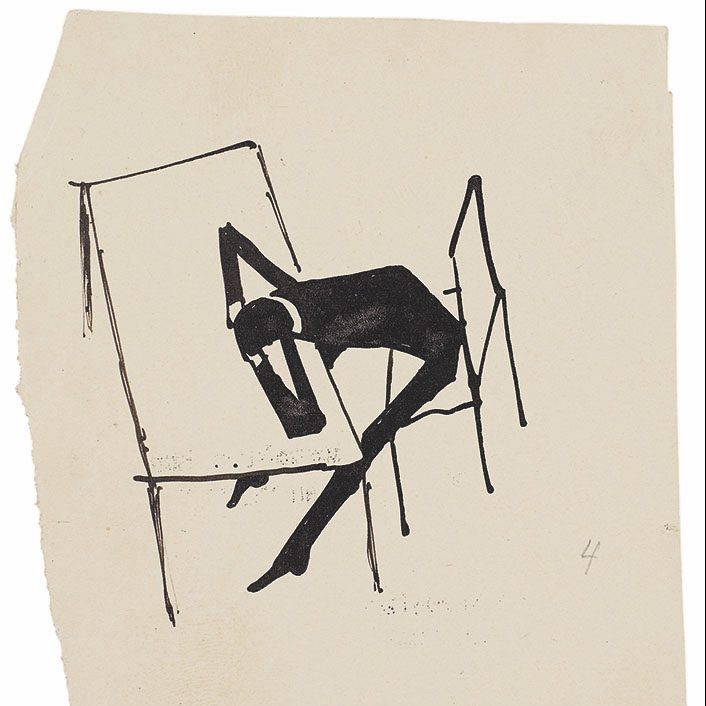

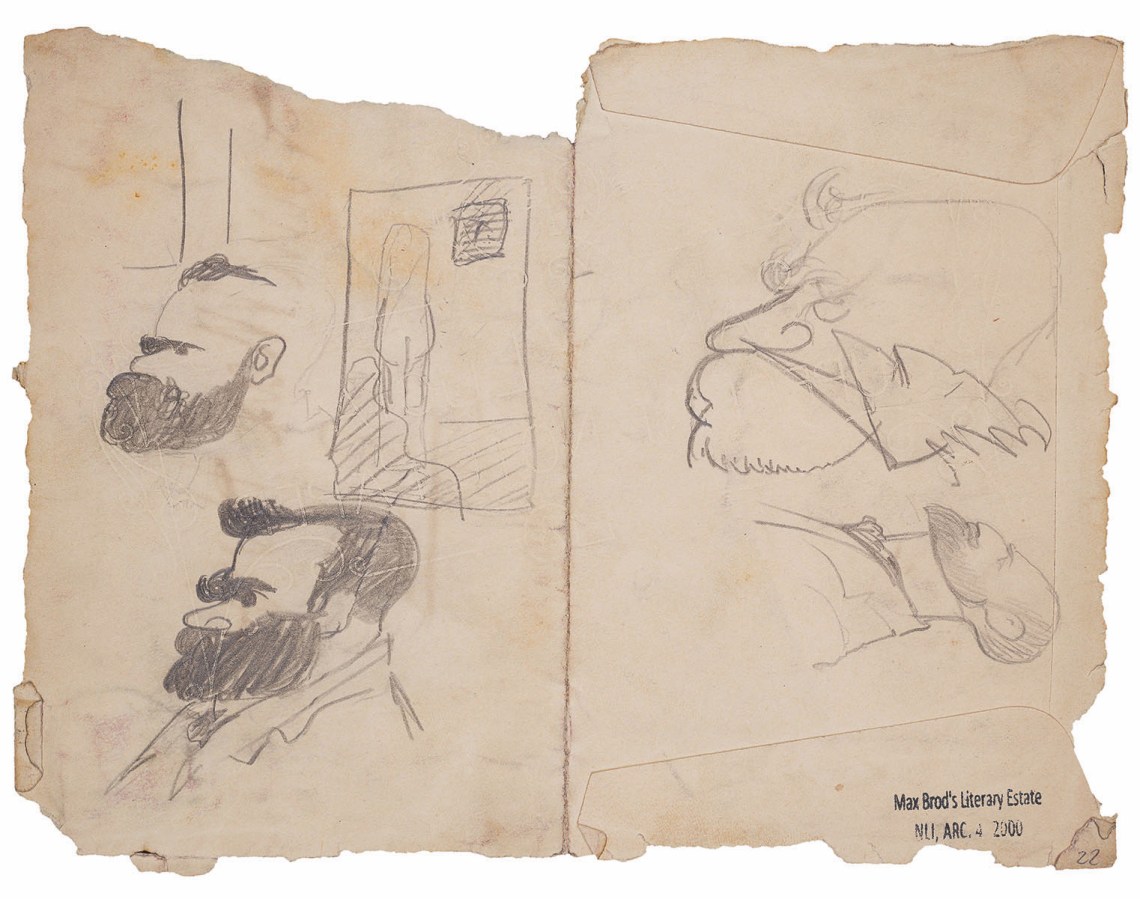

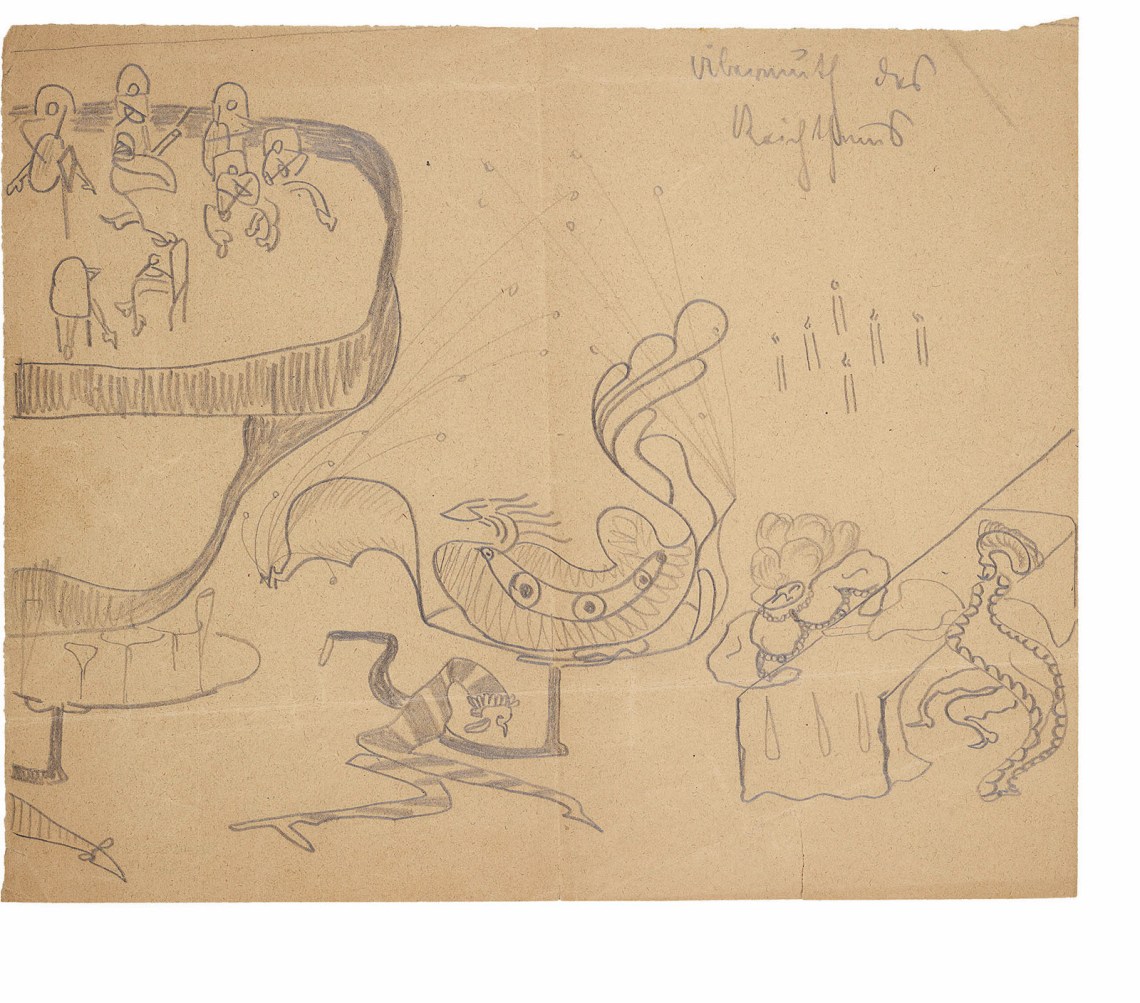

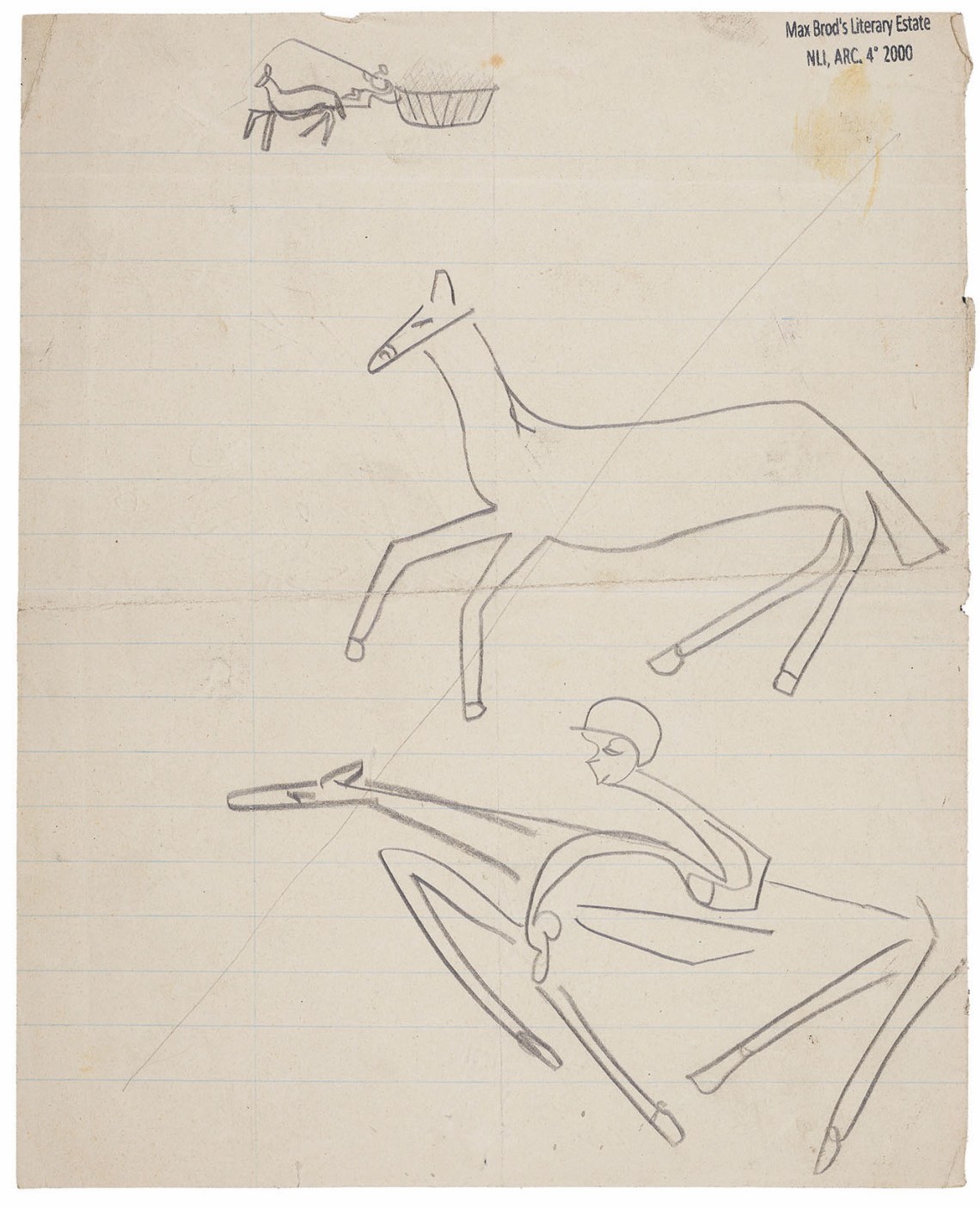

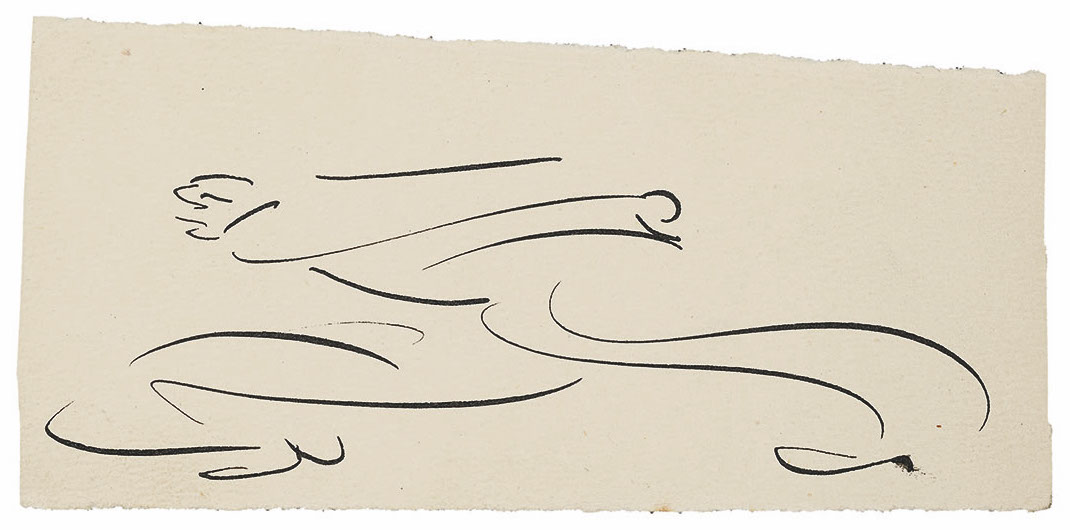

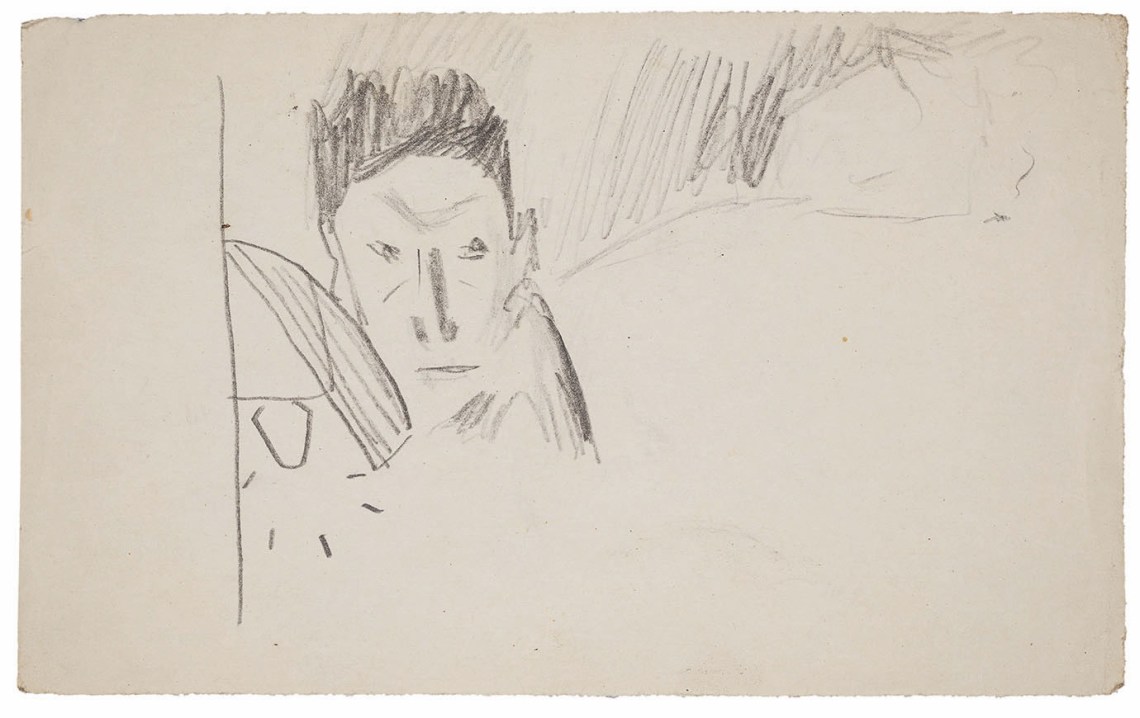

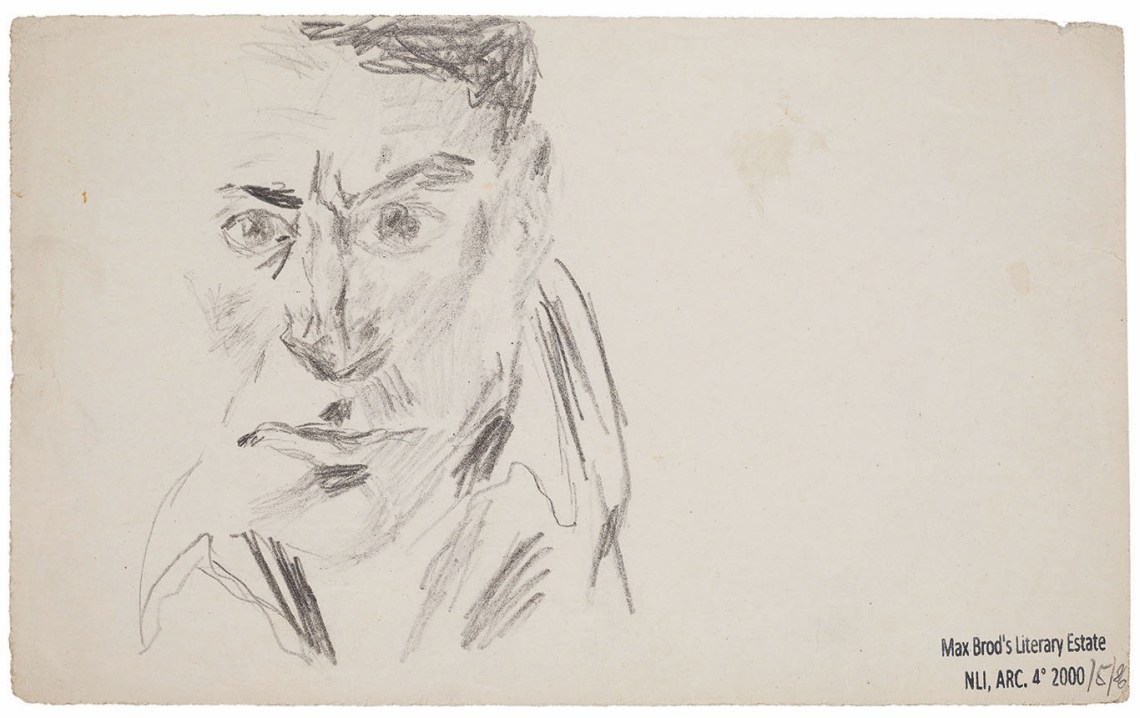

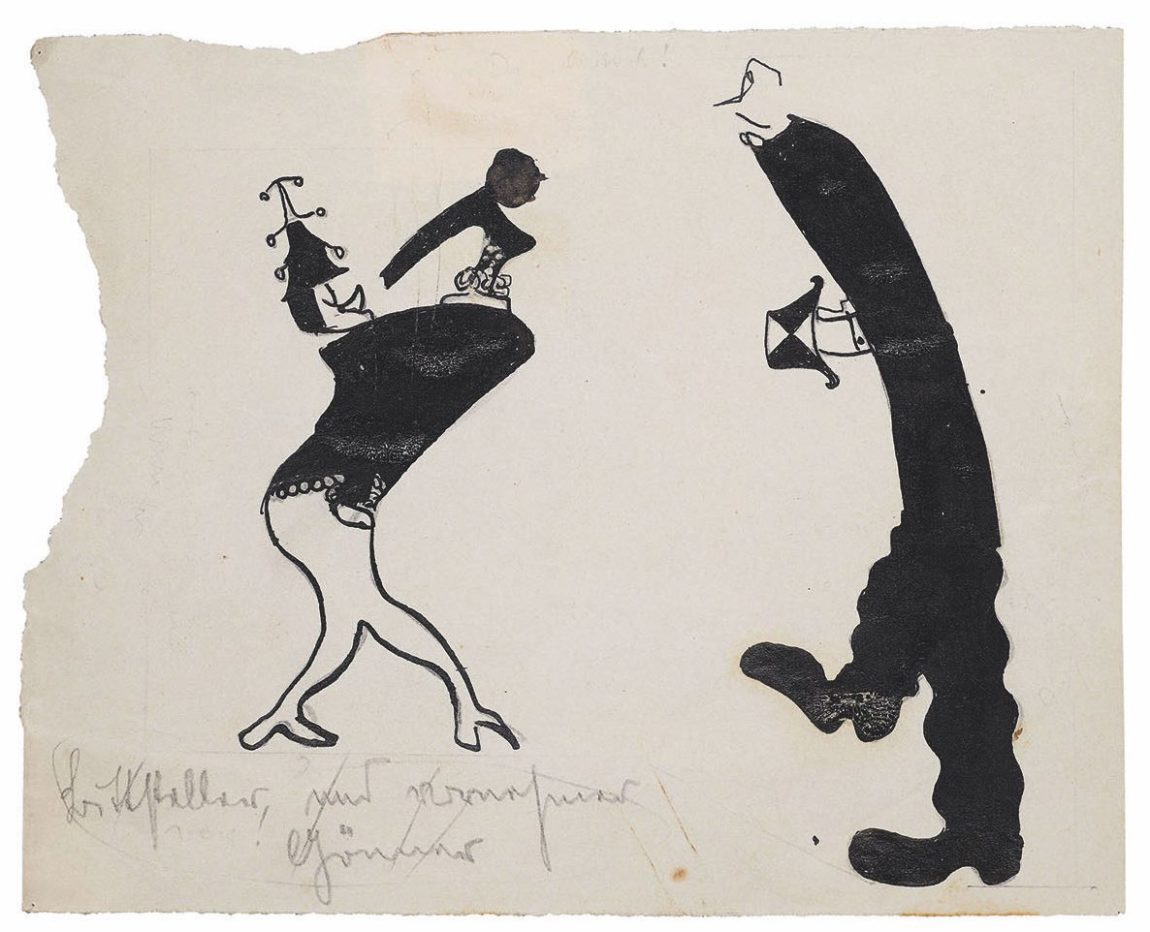

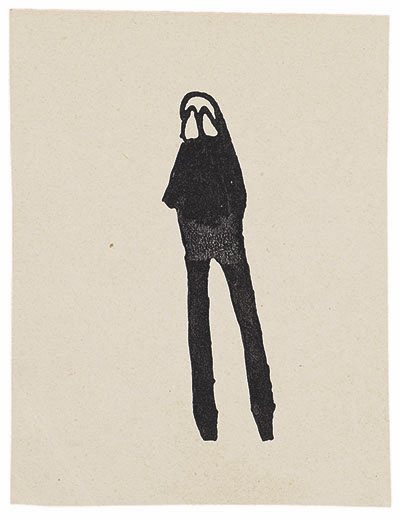

Such an active imagination—the fever for annotation, familiar from Pale Fire or Flaubert’s Parrot, that distorts the inner life of the artist even as it seeks to illuminate it—is required of any reader hoping to get their money’s worth from Franz Kafka: The Drawings, a volume of the writer’s archival sketches and ephemera edited by Andreas Kilcher and Pavel Schmidt. A bearded maestro presides from the back of a business card. A stick figure seems to throttle a mass of squiggles. A harlequin frowns under the chastisement of an irate lump. Two curvilinear ink blots pass each other on a blank-page boulevard. A bushy-browed Captain Haddock-type glowers in profile on a torn envelope and, in the margins of a letter, a wrigglesome delinquent is bisected by a torture device that seems to clearly reference the one from “In the Penal Colony.” Limbs jut out cartoonishly from bodies, loopedy-loop acrobats snake up and down the gutter of a magazine, figures of authority preside in faded pencil, and then there are the stray marks on manuscript pages, neither fully letters nor drawings.

Judith Butler, in their excellent contribution to The Drawings, “‘But What Ground? What Wall?’: Kafka’s Sketches of Bodily Life,” links the fiction and the art when they describe the assorted sketches in pen and graphite as “images, as it were, that have broken free of writing, even as they reiterate, in a different register, some of its most fundamental concerns.” All of which is to say, Kafka’s visual art is not devoid of interest to the enthusiastic reader of “The Metamorphosis” and The Castle, even if none of the 163 scraps and stray drawings assembled here reveals an iota of secret artistic genius.

Some of these drawings you may have seen before. Kafka’s spindly penitents have graced the covers of his paperbacks since the 1950s, and a few have been included in monographs and catalogs. But the vast majority appear here for the first time. The story of their long journey into print is the volume’s principal accomplishment, and more than makes up for the fact that the images aren’t exactly Egon Schiele. Spirited away to Palestine as the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, transferred to four safe-deposit boxes in Zurich during the Suez Crisis of 1956, then subject to a succession of teases at publication that only increased the mystique around them, the sketches are now published only thanks to a decision by the Supreme Court of Israel in 2016. This was the culmination of a circuitous ten-year trial that finally overruled the claims of their parsimonious executor Esther Hoffe and her heirs and entrusted the archive to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. All of this, as is the case for the preservation of most of Kafka’s work, was made possible by the redoubtable Max Brod.

Advertisement

What a guy, Max Brod. Along with Friedrich Nietzsche’s boon companion Franz Overbeck and Einstein’s patient sounding board at the Bern patent office, Michele Besso, Brod is one of the great second bananas in intellectual history. Famously, Max Brod refused to burn his friend’s unpublished manuscripts upon his death and so gave us one of the most enigmatic repositories of psychological irrealism on file in any language. Kafka made the same request regarding his humble drawings, and this time Brod wisely decided neither to incinerate nor to publish. With the drawings entrusted to Brod, stamped with his imprimatur as executor, and then bequeathed to Hoffe, his mistress, the public might well imagine that they were in store for a visual bonanza comparable to that of Kafka’s prose.

Brod likely reasoned that the promise of an invisible body of work would tantalize a critical establishment that treated him increasingly harshly following the growth of Kafka’s popularity worldwide. Smarting from the criticism of Hannah Arendt (whose essay “Kafka: A Revaluation” sought to rehabilitate the writer from Brod’s gloss) and regularly faulted for his presentation of Kafka as a gossamer mystic—Adam Thirlwell cautioned in 1999 against reading Kafka “too Brodly”—Brod launched a series of exhibitions and publications that all ended up hastily canceled or withdrawn, exaggerating the size of the trove and what it contained while managing to damage much of the material in the process (evidence of tearing and generally shoddy preservation is extensive in the new volume). With its rigmarole, suspended conclusion, elements of incompletion, and dashed hopes for deliverance, the whole story is pure Kafka. It renders the great writer, in Butler’s words, as the figure who “seeks its dissolution into line, motion, and air, a fugitive figure, eluding capture.”

Though any attempt to know Kafka more intimately on the strength of his drawings is likely doomed to disappointment, he was in fact a patron and dutiful practitioner of the visual arts. In his essay in this volume, Kilcher makes clear that Kafka attended lectures and drawing classes and even became a member of the informal Bohemian art-appreciation society “the Eight,” almost all of these endeavors facilitated by Brod. Kafka was captivated by the Borghese Gladiator he observed at the Louvre in 1911 and susceptible to any number of fashions in the art world, including Japonisme’s stark minimalism. Perhaps most crucially, he enjoyed the friendship and encouragement of the brilliant and macabre Austrian printmaker Alfred Kubin, whose lone novel, The Other Side, vies with Amerika for inscrutable austerity.

The drawings are not entirely ancillary to the writings. The contrast they offer is like that of the plans the explorer is shown in “In the Penal Colony,” which detail, in a “labyrinth of lines crossings and recrossing each other,” the function of the sinister torture device on display. Though they seem impossible to decipher, as though made at random, the explorer is told that they are “clear enough.” “It’s very ingenious,” says the explorer, “but I can’t make it out.” Where the stories are reticulate with mystery, the drawings are a blank space in which the viewer improvises his impressions.

Kilcher notes that Kafka’s appreciation of visual art consists of a kind of terror of the literal language of drawing, which he considered a threat to the suggestive ambiguity he courted in his prose. In Kilcher’s account, he thought that “the failure of writing is compensated for by the image,” and went to great lengths to avoid having his own books illustrated, writing to one publisher that a certain frontispiece was “too pretty.” But over one hundred years of artists’ renditions have not been sufficient to erode the all-but-unspeakable disquiet at the heart of Kafka, nor are these assorted doodles likely to dislodge the language that still sticks in our throats. In other words, don’t sell yourself short, Franz.