At heart he was an archivist, and what he archived was his life. Within his hermetic realm he was utterly logical and everything he did made perfect sense. A letter enclosed with a photo of Victor Borge recalled Borge’s overcoat, which he’d once “unsuccessfully tried to steal.” Reminding him: Sonja Sekula had once stolen a mink coat! The gravestone store on Suffolk Street, mentioned in a past letter, was now a Knoll’s showroom. And Sonja was dead, two years ago already. His mind was like a game of telephone caught in a dream. He was an exhaustive collector, a gleaner, a cross-indexer. His works—letters, collages, relief assemblages—were built up from the archive, and never fully complete: he loved to reshuffle and rework.

“I’m interested,” Ray Johnson said, “in things that work like tape machines and places like drug stores.” He was, in other words, an American artist of the 1960s. The one with a sense of humor. “New York’s most famous unknown artist.” He caught the end of Abstract Expressionism and anticipated Pop; was friends with Andy Warhol, John Cage, and Ad Reinhardt, but remained underground. He could hardly sell out when barely anyone understood what he was offering. “He was thought of as an artist,” said Roy Lichtenstein in the 2002 documentary How to Draw a Bunny, “but very few people saw any of the art.” Dorothy Lichtenstein goes a step further. “It was hard to tell exactly what his role” was on the scene, she said. “Other people seemed to be having exhibits or going after shows or doing work, but Ray seemed a lot vaguer. I was never quite sure what he did.”

His first shows were on sidewalks, in Grand Central Station, down in Peck Slip. He worked by his own system and on his own time. He’d wander around Manhattan, taking his “moticos”—irregularly-shaped collages, made on laundry shirt cardboard—on strolls, staging them around the city or draping them on friends. A day’s work, he claimed, might involve walking to every mailbox in Brooklyn, or else he’d visit his idol, the artist Joseph Cornell, in Queens. He once got a helicopter to drop sixty footlong hot dogs on Ward’s Island. Otherwise he might spend the day on the phone, or fussing over an envelope. For two years he made a Book About Death “to stay alive.”

He called himself a Dada character when he might have just said a romantic. He lived in “voluntary poverty” in a bare room with one stack of books piled up to the ceiling and a string in the middle of the room “dividing up the space.” His works rarely sold, and whenever there was interest, he’d pull out an absurd figure, hundreds of thousands of dollars for a few collages, and be furious when the buyer backed away. He didn’t care for money, but liked the idea of hawking his art: he described himself as a “Fuller Brush man” visiting collectors with a box of works tucked under his arm. To those in the know, he was a genius; to the ones in power, a nuisance. His “Nothings,” wry takes on Fluxus “Happenings,” might involve dumping boxes of wooden dowels down a stairwell, just out of earshot of the invited audience. “It sounded to me like a waterfall, or coal going down a chute,” he said. He thought the joke was funniest when others weren’t in on it. Richard Lippold, his boyfriend of nearly thirty years, described him as “indifferent to all the machinations of life…Incorruptible and, in this sense, unmanageable.” In early 1995 he committed suicide, jumping from the Sag Harbor bridge and appearing, to onlookers, to be backstroking out to sea. He could not swim.

When he died the house in Locust Valley where he had lived for three decades was full of neatly stacked boxes, packed with art and marked with labels like “Franz Kafka,” “Lucky Charms,” “Maybe,” “John Hancock.” “I’m very fond,” he said, “of the idea of the message in the bottle.” He liked the thought of it “never being” found. In 1992, following his last exhibit, he picked up what he called a “new career as a photographer” and went on to take over five thousand photographs. A few he mailed, mostly as photocopies, but most he stored away, still filed with their negatives and receipts. They were found soon after his death, but it took years for them to be registered as artworks. It was a final message, prank, secret, or gift.

A selection of these photographs, none of which have ever before been exhibited, is featured in PLEASE SEND TO REAL LIFE: Ray Johnson Photographs at the Morgan Library. Neither a “corrective” nor an “addendum,” as so many posthumous presentations are called, the exhibit is a recalibration, reframing his past work and introducing a new way of thinking. Call it wish fulfillment from beyond the grave. Johnson always understood that secrets have to circulate.

Advertisement

*

Johnson got his start as a painter, making tiny bright mosaic-like works reminiscent of Paul Klee. He had learned a syntax of color and form from Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, where he studied from 1945 to 1948, but never settled into the medium. The canvas was too static (he told John Cage he wanted to push pins through the back of the canvas so they would poke out); his own method too formulaic. In the mid-1950s, he destroyed these works—he burned them in Cy Twombly’s fireplace—and started again. He thought like a collagist; now he would work as one.

He worked small, at postage-stamp or postcard size. The collages are the results of his wanderings, whatever detritus caught his eye—cigarette logos, train tickets, laundry receipts—and embed his perennial obsessions: snakes, the movie star Anna May Wong, false eyelashes. To these taut landscapes he’d add bits of paper, scraps of phrases, abstract geometric forms. He took elements of Pop: celebrity, mass-market advertisements, cartoon imagery. But in his hands, these became less “appropriations” than phantasmagorical riffs. (His dreaminess had will.) He called his collages “moticos,” an anagram of “osmotic,” a chemist’s term to signify concentration. And they really are only collagelike: closer to emblems of jumpiness or tiny imagist poems. They recall Cornell’s description of his shadow boxes as “poetic enactments, verbal bibelots, static theater—anything but mere works of visual art.”

Since high school Johnson had been mailing one-of-a-kind collages and drawings to friends and strangers, with the prompt “Please add to and return to…” He ramped up his mailings throughout the 1950s, and in 1962 his friend Ed Plunkett formalized his loose group of addressees with the name the “New York Correspondence School.” Before that, Johnson had called it a game. Every element of the letter—enclosures, stamps, return letterhead—had a particular meaning, tailor-made for the recipient, or for the times. To Lucy Lippard he sent an old “formal portrait of a miserable-looking family,” the photographer’s address near Lucy’s on the Bowery. In the 1980s he had a stamp made that read “Collage by Sherrie Levine,” playing off the artist’s practice of appropriating images of others. For a Gertrude Stein fan he diagrammed “How to Draw a Tender Button.” To Shelley Duvall he drew her eyes, doll eyes that roll. “It’s a marvelous art form, the letter,” said Johnson, light and sweet, “full of wonder and surprise.”

The School grew exponentially, across the US and internationally, and everyone in New York—anyone who was anyone—was sending him letters, artworks, stray bits of stuff. (Gary Indiana recalls sending Johnson empty toilet paper tubes.) The network included famous artists (Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, John Baldessari), downtown artists (Peter Hujar, Lynda Benglis), the critics, curators and dealers of the art world. Or else he’d write to movie stars (like Joan Crawford and Betty Grable), mostly without introduction, or to people with a certain cachet (he sent months working on his letter to Jacques Derrida). Or else to people he found in phone books who had interesting names, or others who were also named Johnson. It all happened somehow. He loved the poet Marianne Moore’s tricorne hat, its motico-like shape, so she was in. It’s hard not to be sentimental about something so guileless operating on such a scale, all through a solitary man living on nothing. But it’s hard to imagine who else could have done it. Nothing was the point. Why not give it away?

*

In June 1968, in a confluence he might have liked, save for the event, Johnson is mugged at knifepoint on the same day Warhol is shot by Valerie Solanas. It was the end of some kind of era. He leaves New York and moves to Long Island, where he spends the next three decades in relative isolation, slowly breaking off most of his ties with the art world. It would have been called a drop out if he’d ever been considered on the inside.

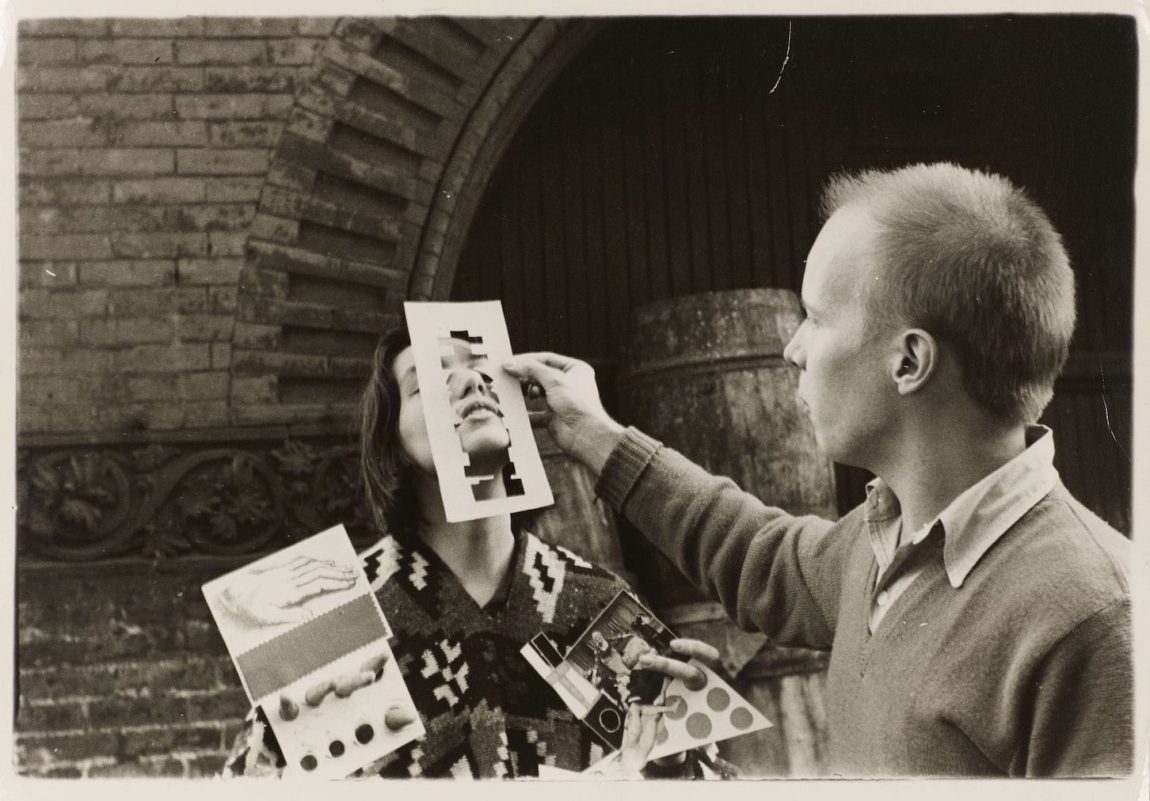

Photographs, as archive documents and performance records, had been vital to Johnson from the beginning. In 1955, he had arranged and shot hundreds of early moticos on the floor of a warehouse. In this period he often staged moticos on sidewalks, or in other disused spaces in lower Manhattan. These were occasionally documented, often at his request, by his friend Elisabeth Novick, as were his “motico-walks,” during which he’d cover friends and strangers with collages like living galleries (called the first “informal Happening” by Suzi Gablik). He might have been an American, but he never believed in “starting fresh.” His new career would be a return to the past.

Advertisement

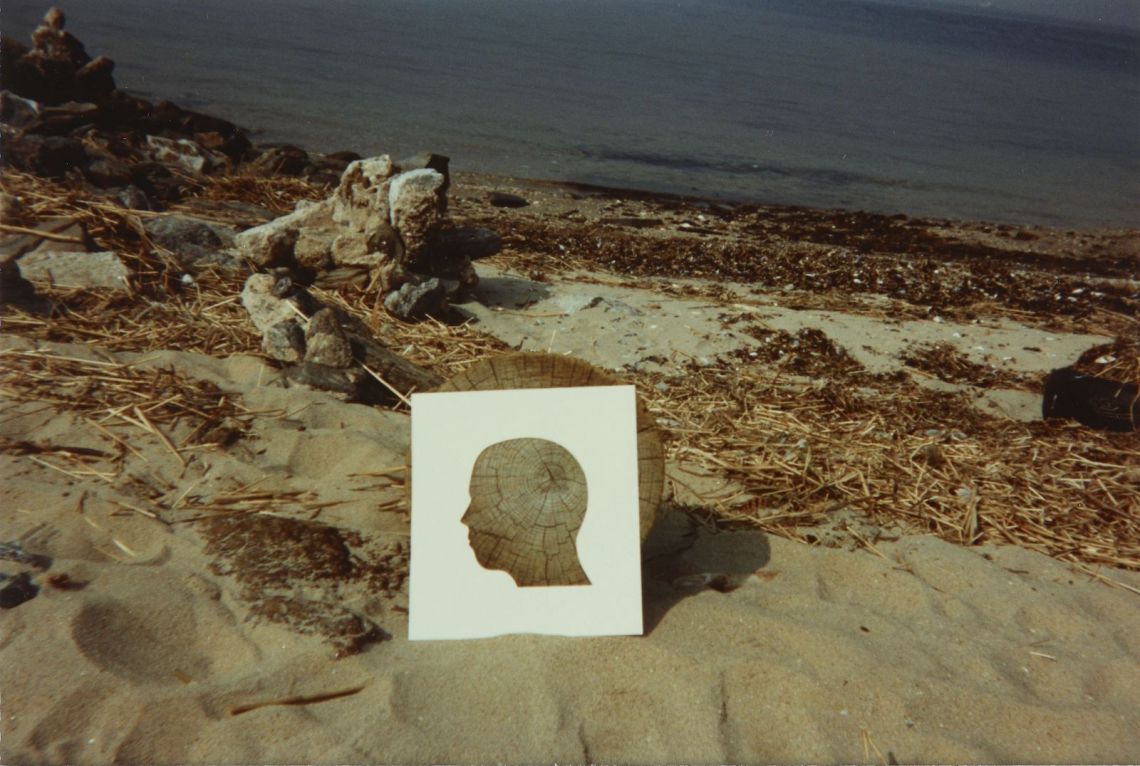

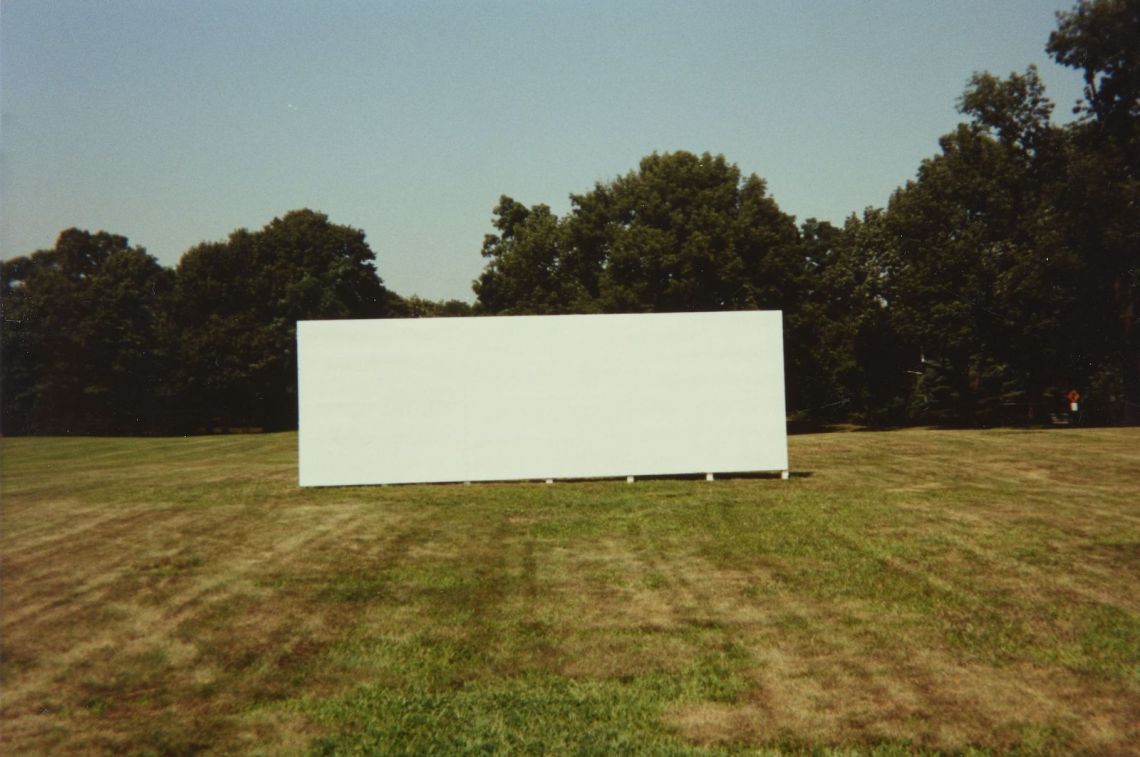

Echoing the walks he used to take on the Lower East Side, on most days he would pick up his collages and moticos and go for a drive. Almost as if they were friends visiting from out of town, he’d take them around, to the beaches, stoops, and back alleys he knew well, or to places he thought might suit them. He’d arrange them just so but without any fuss, or place them on himself, and take a photo, using what he called his “throwaway camera” (basic point-and-shoots, first Kodaks, then Fujicolor Quicksnaps). It was as if he was creating performances in the minor key, with the artist as his own audience. Almost every week he’d end up with a roll of film.

I’m afraid I’m making it sound like these photographs are the delusions of a lonely man as opposed to considered artworks. (As though the distinction between the two is ever clear.) This isn’t the case. They are as full of wit, as deliberate, and as conceptually loaded as any of his past work. But he had always lived his art, so that these late pictures hue differently, weigh heavier, is only natural. They bear the whole of his life: indexes of his relationship to his works, and of his artwork’s relationship to his surroundings.

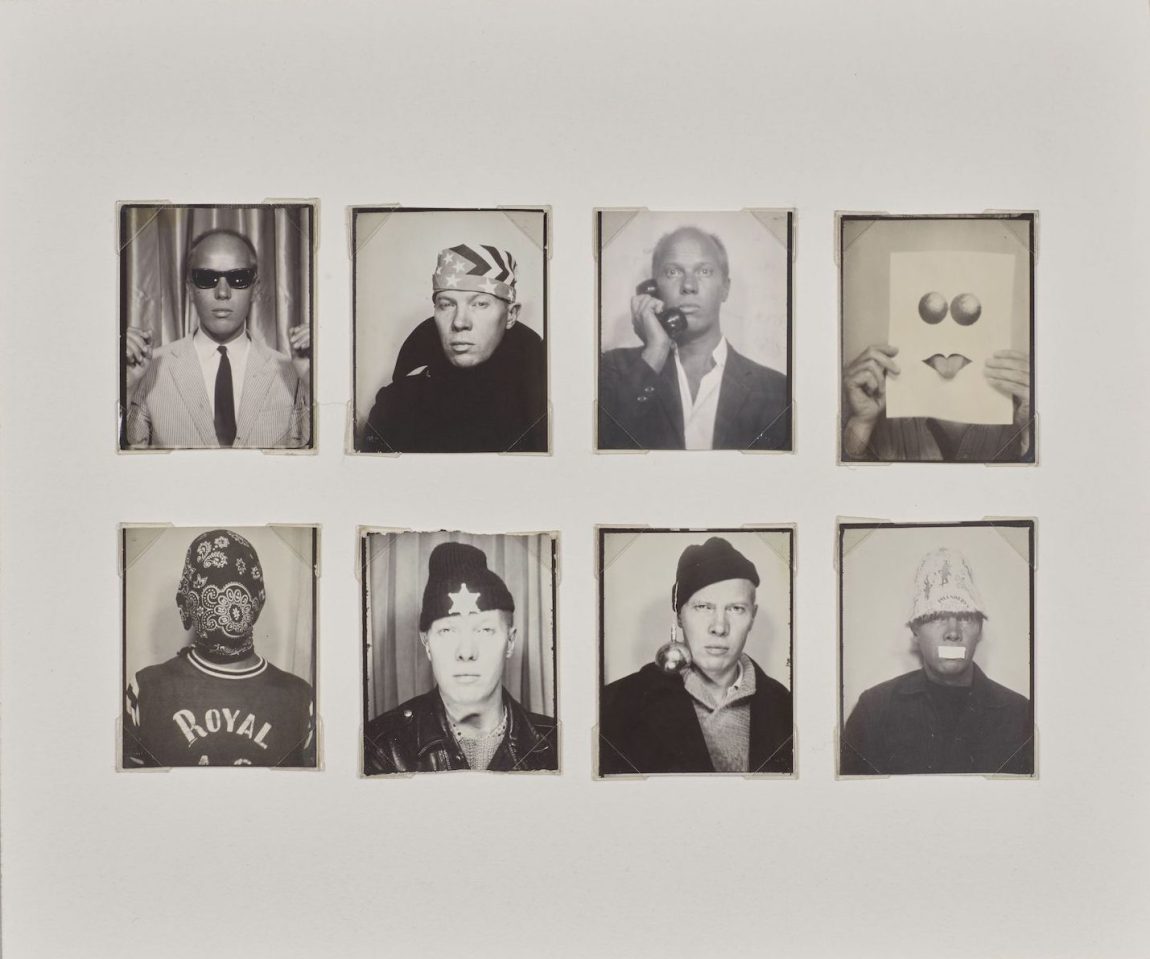

Many of the photographs in the exhibit feature Johnson, and none could really be described as self-portraits. A wink at the idea, maybe. One photograph shows a towering column of identical letter-sized photographs of Johnson stacked atop one another. The face—his face—loses specificity as the eye moves up; the final image is just the suggestion of a head. It’s not unlike a game children play, and adults too: now you see me, now you don’t, the hide-and-seek that portraits are always subject to.

He liked whatever could multiply the image: doubles, mirror effects, shadows. Sometimes that form is literal: cornflower blonde twins in plaid smiling in front of a cheap farmhouse. Other times it’s by design, as in a glossy blowup of Marilyn Monroe propped up beside its photocopy. The Xerox disintegrates the image and throws her features into relief. She’s never looked less alive. Another shows a cheery self-portrait alongside a photograph of Elvis, deadpan and glazed behind the dashboard of Johnson’s car. (Johnson, an avid fan, would have known that Elvis was a twin, his double stillborn.) This is teenage fan work pushed to the extreme, made by an adult who knows that death is the shadow of iconicity.

His collage and silhouette works had always embedded his heroes, as if depicting them would render them alive or close to him. His photos share this magical thinking. He shoots his legs in shadow above Lee Friedlander’s book Like a One-Eyed Cat, open to a page with Friedlander’s own self-portrait in shadow; another picture again portrays his shadow, lined up against a famous Walker Evans portrait. He seems to be grafting himself onto the history of photography, albeit as a wraith.

Some images function as calling cards or scrappy marketing materials: hand-painted signs that read “Ray Johnson The Paris Correspondence School” or “Photo by Ray Johnson” positioned below schoolyard plaques or tucked behind bricks; his vertical moticos draped along a lone car, or embraced by a Ronald McDonald statue. Other photographs are visual gags, as in photos where he brings a phone up to one of his silhouettes, dead air talking to a mute object.

The photos are imagined worlds and documents of loneliness. His works had become his playthings, the world a kind of living board game. In several photos we see Johnson’s outstretched hand—palm up against the ocean before him or holding a cut-out of a crescent moon before looping train tracks. The gesture looks something like a wave. “I don’t know if I really have time,” he said, “to understand my work.”