Dominique-Vivant Denon, the subject of my piece in the November 19, 2009 issue of the New York Review of Books, is known above all as the first Director of the Louvre—which, under his guidance, became the first encyclopedic public museum. But he was also an artist prized for his travel sketches and engravings. Since I could only touch on this aspect of his career briefly in my piece, I offer here some further notes and selections from his work.

Denon settled in Venice on the eve of the French Revolution, with the intention of creating his own engraving studio, and marrying his adored mistress, Isabella Teotochi. The Revolution changed all that. He had to return to France, during the Reign of Terror (under the protection of the painter Jacques-Louis David, associate of the Jacobins), to prevent the expropriation of his property. Then he was enrolled in General Bonaparte’s Egyptian Campaign in 1798, as one of its “savants.”

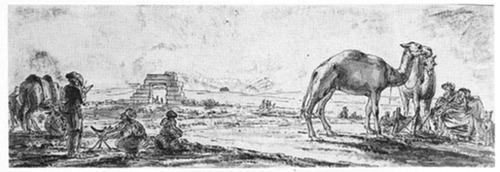

The Egyptian expedition offered an opportunity to feed the cultivated public’s insatiable curiosity for visual travelogue (photography was still some thirty years in the future). Denon became a first-rate sketcher of Egyptian ruins (his work recalls Piranesi’s views of Roman ruins, from a few decades earlier) and antiquities. The sketches were done on the spot, in haste, by the artist as he arrived on horseback with the army—the contemporary equivalent of the hand-held camera, if you will. In one of these sketches (shown above), Denon includes himself, sketching the ruins of Hierakonpolis.

There is a fluid charm and grace to the drawing, which represents Denon in what he calls his “ruined” clothing, next to his horse, with the ruins in the distance—and that somewhat startlingly large camel to the right. One wonders how many European representations of the camel there had been before this?

These sketches were engraved, to figure in Voyage dans la Basse et la Haute-Egypte pendant les campagnes du général Bonaparte, the magnificent and thorough account that Denon both wrote and illustrated, published in two large volumes in 1802, to great acclaim.

From earlier, no doubt, is his Le Roman universel (“The Universal Novel”—or in a more apt translation, “The Same Old Story”), which with some of the worldliness of his masterful erotic novella No Tomorrow (Point de Lendemain) gives us, in a kind of comic strip (read it from left to right), the story of a liaison, from meeting to separation, with clear but gracefully rendered scenes of lovemaking in the middle.

We may be reminded of Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde, and Max Ophuls’ film adaptation—though Denon’s version seems somewhat less world-weary. For all his sophistication, he is not, one feels, a cynic.

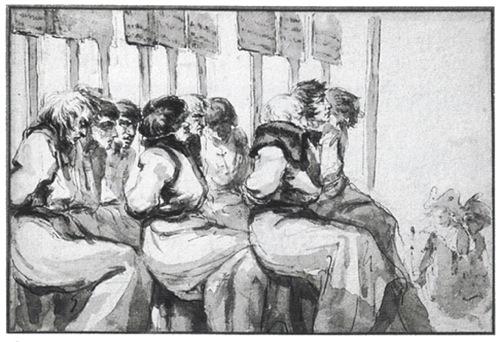

It’s a sign of the tumult of the period Denon lived through that the mood of the next image should be so strikingly different. This pen-and-ink drawing irresistibly evokes David’s famous sketch of Marie-Antoinette, her hands tied behind her back, seated in a tumbrel on her way to the guillotine.

These members of the Revolutionary Committee of the “section” named Bonnet-Rouge (all Paris was for a time divided into revolutionary “sections”) have also been sentenced—but probably not to the guillotine. The drawing dates from November or December 1794, after Thermidor, the turning point in the French Revolution that put an end to the Reign of Terror. The guillotine had fallen out of favor for common crimes: the committee members seem to have been found guilty of corruption. It’s likely that these sometime revolutionaries are undergoing a shaming punishment, mounted on a platform under signs proclaiming their misdeeds—and shivering: the final weeks of 1794 were notoriously frigid. I sense a kind of dispassionate historical gaze in Denon’s work here—surely one of his most accomplished historical evocations.

It is something of a retreat, in time and in style, to look at one of Denon’s self-portraits done, as he put it, “in the Flemish manner.”

It probably comes from his pre-Revolutionary time in Venice, and he self-consciously evokes an archaic style, setting himself, amidst old vases and busts and books, in a kind of Ruysdael-like decor. It may most of all point to the enormous prestige of Rembrandt, especially in portraiture. Like most self-portraits, it’s done in a mirror—Denon was right-handed.

Finally, I find myself circling back to the Egyptian Campaign, and Denon’s remarkable visual (as well as his written) travelogue. “Remember that from the height of these pyramids forty centuries are looking down at you!” Napoleon supposedly told his troops on the eve of the Battle of the Pyramids. Denon found the pyramids a largely depressing monument to a despotic and priest-ridden society (he was a man of the Enlightenment). But the Egyptian temples grabbed his historical imagination.

He found Karnak “sumptuous,” though lacking in finesse and artistically “barbarian.” Nonetheless, he judged the ancient Egyptians to be “giants”—and at moments, as in the outer gates of Karnak, “geniuses” as well. Denon’s transmission of Egyptian scenes would provoke a wave of Egyptomania in French decorative style—including a sumptuous set of dinnerware executed, under Denon’s direction, for the Emperor Napoleon at the Imperial Manufactory at Sèvres.

Advertisement