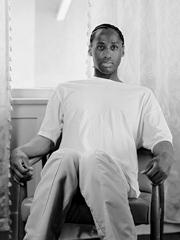

When Troy Erik Isaac was first imprisoned in California, his cellmate made the introductions for both of them. “He said to me, ‘Your name is gonna be Baby Romeo, and I’m Big Romeo.’ He was saying he would be my man.” Troy was twelve at the time. A skinny, terrified little kid, he accepted the prisoner’s bargain being imposed on him: protection for sex. He wasn’t protected, though. Soon he was attacked and raped at night by another cellmate, a sixteen-year-old. He told staff he was suicidal, hoping to be placed in solitary confinement, but they ignored him; the rapes continued.

In 2005, the Department of Justice investigated a juvenile facility in Plainfield, Indiana, where kids sexually abused one another so often and in such numbers that staff created flow charts to track the incidents. Investigators found “youths weighing under 70 pounds who engaged in sexual acts with youths who weighed as much as 100 pounds more than them.”

Reporters in Texas, in 2007, discovered that more than 750 juvenile detainees across the state had alleged sexual abuse by staff over the previous six years. That number, however, was generally thought to under-represent the true extent of such abuse, because most children were too afraid to report it: staff commonly instructed their favorite inmates to beat up kids who complained. Even when the kids did file complaints, they knew it wouldn’t do them much good. Staff covered for each other, grievance processes were sabotaged and evidence was frequently destroyed. Officials in Austin ignored what they heard, and in the very rare instances when staff were fired and their cases referred to local prosecutors, those prosecutors usually refused to act. Not one employee of the Texas Youth Commission during that six-year period was sent to prison for raping the children in his or her care.

Until now, when such stories have made it into the press, officials have been able to contend that they reflected anomalous failings of a particular facility or system. But a report released this morning by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) should change that. Mandated by the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 (PREA), and easily the largest and most authoritative study of the problem ever conducted, it makes clear that sexual abuse in juvenile detention is a national crisis.

This is a difficult problem to measure, since some inmates make false claims, and some, fearing retaliation even when promised anonymity, choose not to report abuse. Overall, most experts believe that the numbers such studies produce are usually too low. But 12.1 percent of kids taking the BJS survey across the country said they’d been sexually abused at their current facility during the preceding year. That’s approximately 3,220 out of the 26,550 who were eligible to take it.

The survey, however, was given only at large facilities that held youth that have been tried for some offense for at least ninety days. That’s more restrictive than it may sound. In total, according to the most recent data, there are nearly 93,000 kids in juvenile detention on any given day. Although we can’t assume that 12.1 percent of the larger number were sexually abused—many kids not covered by the survey are held for short periods of time, or in small facilities where rates of abuse are somewhat lower—we can say confidently that the BJS’s 3,320 figure represents only a small fraction of the juveniles sexually abused in detention every year.

What sort of kids get locked up in the first place? Only 34 percent of those in juvenile detention are there for violent crimes. (More than 200,000 youth are also tried as adults in the U.S. every year, and on any given day approximately 8,500 kids under 18 are confined in adult prisons and jails. Although probably at greater risk of sexual abuse than any other detained population, they weren’t included in the BJS study.) According to a report by the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, which was itself created by PREA, more than 20 percent of those in juvenile detention were confined for technical offenses such as violating probation, or for “status offenses” like disobeying parental orders, missing curfews, truancy, or running away—often from violence and abuse at home. Many suffer from mental illness, substance abuse, and learning disabilities.

A full 80 percent of the abuse reported in the study was perpetrated not by other inmates but by staff. And shockingly, 95 percent of the youth making such allegations said they were victimized by female staff. 63 percent of them reported at least one incident of sexual contact with staff in which no force or explicit coercion was used; staff caught having sex with inmates often claim it’s consensual. But staff have enormous control over inmates’ lives. They can give them privileges, such as extra food or clothing or the opportunity to wash, and they can punish them: everything from beatings to solitary confinement to extended sentences. The notion of a truly consensual relationship in such circumstances is grotesque even when the inmate is not a child.

Advertisement

Nationally, however, fewer than half of the corrections officials whose sexual abuse of juveniles is confirmed are referred for prosecution, and almost none are seriously punished. Although it is a crime for staff to have sex with inmates in all 50 states, prosecutors rarely take on such cases. As children’s advocate Isela Gutierrez put it to The Texas Observer, “local prosecutors don’t consider these kids to be their constituents.” A quarter of all known staff predators in youth facilities are allowed to keep their positions.

The biggest risk factor found in the study was prior abuse. 65 percent of those who had previously been sexually assaulted at another correctional facility were also assaulted at their current one. In prison culture, even in juvenile detention, after an inmate is raped for the first time he is considered “turned out,” and fair game for further abuse. 81 percent of those sexually abused by other inmates were victimized more than once, and 32 percent more than ten times. 42 percent were assaulted by more than one perpetrator. Of those victimized by staff, 88 percent had been abused repeatedly, 27 percent more than ten times, and 33 percent by more than one facility employee. Those who took the survey had been in their facilities for an average of just half a year. In essence, the survey shows that thousands of children are raped and molested every year while in the government’s care—most often, by the very corrections officials charged with their rehabilitation and protection.

The necessary precautions to prevent this horrific treatment are clear (see the June

2009 National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report, page 159). So far, however, reform has been slow. The Plainfield unit was converted to an adult facility after the Department of Justice investigation; nonetheless, two other juvenile facilities in Indiana were on the BJS report’s list of the thirteen worst nationally, as were two in Texas. In 2005, The Department of Justice investigated the L.E. Rader Center in Oklahoma. Although the state Attorney General’s office “refused to allow the United States the opportunity to tour the Rader facility,” investigators examining documents discovered, among other problems, rampant sexual abuse of the facility’s boys by female staff. It concluded that Oklahoma “fails to protect youth confined at Rader from harm due to constitutionally deficient practices.” But years later, Rader too is on the BJS’s list of worst facilities: 25 percent of its inmates still claim abuse by staff.

A recommendation by the Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS) in New York that judges avoid sentencing children to the state’s juvenile detention facilities unless they pose a significant risk to public safety has received a great deal of press lately, most recently on the editorial page of The New York Times. That recommendation followed multiple revelations of violent, neglectful, and abusive conditions—first in a Human Rights Watch report issued in 2006, then in a 2009 Department of Justice investigation, and finally in the report of a taskforce created by Governor Paterson. Most of the abuses described in these documents were not sexual. Now, though, we are told that the problems in New York are even worse than reported. New York juvenile facilities surveyed by the BJS did not in aggregate perform markedly better than the national average. It turns out that sexual abuse is yet another crisis in the state’s juvenile detention system, as it is across the country.

Unfortunately, such abuse also goes on at appalling rates in adult prisons and jails, as we’ll discuss in an essay we are now preparing for publication: in much higher numbers than have so far been reported in the press. There are effective ways to stop sexual abuse in detention, as we’ll explain. But despite the reports by the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission and the Bureau of Justice Statistics, some important corrections leaders are fighting the necessary reforms. We’ll discuss their influence in the Obama administration’s Department of Justice, and why they are so resistant to change.