Stalin is guilty. On January 13, four days before the first round of Ukraine’s presidential elections, a Kiev court condemned him and six other Soviet high officials for genocide committed against the Ukrainian nation during the famine in 1932-1933. All seven men, of course, are long dead—but the history at issue in the case is very much alive.

The famine certainly did happen, and it was deliberate. In the course of Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan for the industrialization of the Soviet Union, farms were collectivized so that their yields could be appropriated by the state. The resistance of peasants was broken by tens of thousands of executions and millions of deportations. Collective agriculture proved inefficient, especially during the violent transition. When Soviet Ukraine began to suffer a famine in 1932, Stalin ordered the seizure of grain, the slaughter of livestock, the isolation of Ukrainian villages from the outside world, and the sealing of the Ukrainian Republic’s borders.

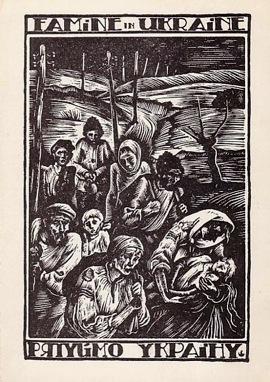

The victims of the famine died slowly, in humiliation and in agony. Peasants made their way to cities, where they starved on the sidewalks. In the countryside, people ate grass and roots and worms. Women prostituted themselves for bread. Children in orphanages drank each others’ blood and ate their own excrement. Mothers asked children to eat their bodies when they died. Roving groups of bandits kidnapped the weak and vulnerable and sold their flesh. In spring 1933, the villages went quiet. The cattle and horses and chickens were gone. The cats and the dogs, too, had been eaten. The birds stayed away. Burial crews took the dead (and the dying). Those crews kept no good records, and Stalin suppressed the next census. Historians estimate that more than three million people died in Soviet Ukraine.

Then came the Great Terror of 1937-1938, which struck Ukraine with particular force. The “kulaks,” a Russian word for prosperous peasants, were the first target. Very often these were Ukrainians, people who had somehow survived collectivization, famine, or the Gulag. They were condemned by an “operational troika”—a party member, a state police officer, and a prosecutor. The troikas would review hundreds of files a day and almost always issue one of two verdicts: death or the Gulag. A minute-long examination of a file was the entire judicial process; the defendants were not present, they did not hear the case, they had no legal defense. If they were sentenced to death, they were taken to a forest, or a field, or a garage, and shot. If they were sentenced to the Gulag, they learned the verdict on the train to Siberia. Of the 681,692 recorded death sentences in the Great Terror, 123,421 were carried out in Soviet Ukraine. The Soviet death pits are still being discovered.

The outgoing Ukrainian president, Viktor Yushchenko, welcomes the Kiev court’s verdict against Stalin. Having placed fifth in the first round of the elections on January 17, he knows his term of office will soon come to an end. Yushchenko has worked hard to institutionalize a Ukrainian national memory these last five years, and knows that neither Viktor Yanukovych nor Julia Tymoshenko, the two presidential candidates competing in the run-off election on February 7, will take anti-Stalinism to such lengths—not least because it annoys Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. In Russia, in contrast to Ukraine, Stalin still enjoys a certain popularity; and some politicians have assailed the court ruling as a provocation. This would only be true insofar as Russians choose to identify themselves with Soviet leaders: most of the defendants (including Stalin himself) were neither Russians nor born within Russia’s present boundaries. The difference in attitudes towards the Stalinist past is in some measure the result of Yushchenko’s preoccupation with history. He seems to hope that this verdict will make the label of genocide impossible to undo, since it “shifts any discussion of the famine in Ukraine from the political to the legal realm.”

Should history be a matter of law? This trial, approved by Yushchenko and arranged by the Security Service of Ukraine, summons the spirit of Stalinism that it was meant to dispel. Rather than a regular judicial proceeding, the trial was conducted by a modernized troika: a Security Service officer, a prosecutor, and a judge, meeting in closed chambers for a single day, then passing judgment on ghosts. The Ukrainian Security Service, which pressed the charges, is the institutional successor of the Soviet state police of the 1930s. Perhaps this explains why none of the seven defendants were officers of the OGPU, as the Soviet state police was known then? The OGPU were closely involved in the famine as well as in the Great Terror. Vsevolod Balyts’kyi, the head of the Ukrainian branch of the OGPU in those days, might have been considered alongside Molotov and the other five identified in the trial as Stalin’s fellow perpetrators. He threatened local officials with the Gulag, forcing them to collect grain from the starving; and he sealed the internal borders of the republic so that they could not beg in other parts of the Soviet Union.

Advertisement

In this trial, the Security Service of Ukraine served (by its own account) as censor, researcher, friend of the court, and spokesperson. Its directors decided which archival records were classified; then assembled 320 volumes of these to make its case, then proposed how the court might evaluate that material; and finally publicized the verdict as a press release. Thus carried out, the trial exhibited an unfortunate tendency of the post-Communist world: the placing of responsibility for historical research, criminal prosecution, and national memory within a single institution (or a group of closely allied institutions). Until now, access to archives in Ukraine has been easier than in Russia, which means that some young historians are writing dissertations about the Soviet Union in Kiev rather than Moscow. But this verdict is a worrying sign of a new orthodoxy.

There is a better way than legal séances to spread knowledge of the horrors of the twentieth century: keep archives open. There is also a better way to draw attention to Stalinism: treat it as European history. President Yushchenko has called for an international tribunal to judge Stalinist crimes in Ukraine. Simpler would be cooperation among the national memory institutes of post-Communist Europe: rotation of their staff historians from country to country, sharing of documents from archive to archive, and joint research on repressive policies. Without such ventilation, the memory ministries can lurch towards Orwellian nationalism. The European Union, which often fails to take account of historical differences between eastern and western Europe, might fund such cooperation, as a kind of Marshall Plan of the mind. Only international discussion can balance European history, and only a balanced history can serve European understanding.