Every so often, writers outside the architectural profession publish works on the building art that capture the public imagination and make the best-seller lists, most lamentably Tom Wolfe’s wildly misinformed fantasia on early Modernism, From Bauhaus to Our House (1981). Far more benign was Tracy Kidder’s House (1985), a numbingly detailed report on the creation of an architect-designed dwelling for a Massachusetts family. More recently, the architect and educator Witold Rybczynski has mastered the art of explaining the commonplaces and arcana of the architectural process and its products in several books commendable for their lucidity and even-handedness. Now they are joined by Edward Hollis, a British architect and preservationist whose new book, The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories, offers an advanced seminar for graduates of Rybczynski’s introductory courses. Hollis, who teaches at the Edinburgh College of Art, stands apart from other popular writers on the building art in his acknowledgement that architecture is anything but the immutable medium most people suppose it to be. As he writes:

These masterpieces, so called, are too capricious to answer to any one master. They are ruined, stolen, or appropriated. They flit away and reproduce themselves, evolve and are translated into foreign languages. They are simulated, prophesied, and restored, transformed into sacred relics, empty spectacles, and casus belli. It is the contention of this book that their beauty has not been made by any one artist but has been generated by their long and unpredictable lives.

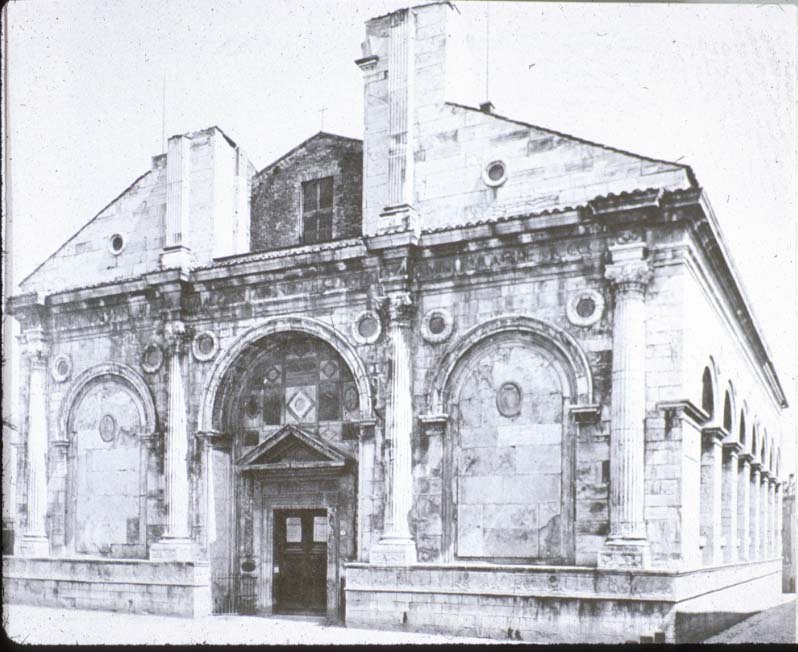

Hollis’ wide-ranging meditations encompass touristic staples (the Parthenon and Notre Dame de Paris); religious shrines (the Santa Casa of Loreto in Italy and Jerusalem’s Wailing Wall); and cult classics (Leon Battista Alberti’s Tempio Malatestiano in Rimini and Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s follies at Sanssouci palace in Potsdam). But no matter how familiar these works may be, he turns the story of each structure and its subsequent transformations into an informative parable about the inevitable metamorphoses of the built environment.

Epitomizing such adaptations, Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia has successively served as a church, a mosque, and now a museum. St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice incorporates many elements looted from Constantinople, some from Hagia Sophia itself: a Byzantine porphyry sculpture of the Emperor Diocletian; a host of golden icons; and the four larger-than-life-size bronze horses of ancient origin—expropriated by Napoleon for the Louvre but returned after his downfall—that prance above its main portal (as replicas, however: the originals are now kept inside the Basilica).

A more recent Venetian is the casino hotel of that name in Las Vegas, which features a fake St. Mark’s campanile, Doge’s Palace, Grand Canal, and Rialto Bridge. Hollis observes that this exercise in architectural escapism is not terribly different from Hadrian’s Villa at Tivoli or Schinkel’s Roman Baths at Sanssouci.

The Venetian has been so profitable that in 2007 the Chinese government was persuaded by the hotel’s majority shareholder, Sheldon G. Adelson, to build a replica of the replica in Macao, the former Portuguese island colony and the Vegas of the Far East. In a Power Point pitch, the American promoters to Vice Premier Qian Qichen in Beijing projected a motto summing up the Möbius-like contortions at play: “Authenticity is the basis for fantasy.”

However, Hollis’s thesis of architectural mutability is a somewhat mutable thing in itself, in that great buildings convey their greatness in a host of different ways. His argument holds up better in some chapters than in others, most notably where the absence of known master builders supports his welcome insistence that the Great Man Theory is particularly inappropriate to an art form that is essentially collaborative, both in a structure’s initial creation and in the many hands that leave their marks on it over time.

Hollis’s prose sometimes soars, as in this scintillating evocation of the Alhambra’s most celebrated inner sanctum:

The Court of the Lions was so cunningly wrought that it appeared to reverse the very laws of gravity. The marble columns that supported the arches seemed to hang down from them like tassels, and the walls were like screens of petrified lace, through which light could be seen. The rooms that opened off the court were vaulted with domes composed of thousands of tiny stalactites that scattered the sun in constellations of light; they seemed to drip down from the heavens, rather than rest upon the walls.

Less convincing is Hollis’s chapter on the Hulme Crescents, a high-rise English housing estate in Manchester, which opened in 1971 and was demolished in 1993. An even more short-lived American public welfare development, George Hellmuth and Minoru Yamasaki’s Pruitt-Igoe housing project of 1954–1955 in St. Louis, fell to the wrecker’s ball in 1972, just in time to become Exhibit A in the ascendant Postmodernists’ case against the Modern movement.

Advertisement

Although both these slum-clearance schemes were initially praised, they soon fell into disrepair and in due course were seen as breeding grounds for crime and anomie. That indictment was pressed by neoconservative writers who argued that the architectural conceptions themselves caused delinquent behavior.

To his credit, Hollis points out that the withdrawal of government subsidies in Britain under Margaret Thatcher (and in the US after the Great Society) had a more direct effect than any design flaws in turning a workers’ paradise into a Clockwork Orange dystopia. But he has little evident sympathy for idealistic social visions gone awry, and writes that however well-intentioned, “every future is followed by another—blueprints for everlasting utopia would, like all plans, be cast aside in pursuit of others.”

If the author’s chapters on the Hulme Crescents, the Berlin Wall, and the continuing struggle over the Temple Mount in Jerusalem lack the enchantment of his evocations of historical monuments, he can be blamed for nothing more than deciphering the latest handwriting on the wall with unremitting clarity. Here he provides the ground for a reinvigorated public discourse on the role of architecture in contemporary society, which makes even his more debatable assertions worthy of wide consideration.

Edward Hollis, The Secret Lives of Buildings: From the Ruins of the Parthenon to the Vegas Strip in Thirteen Stories (Metropolitan Books, 2009)