With the unemployment rate stuck at 9.6 percent, President Obama used his Labor Day speech in Milwaukee to announce a new initiative to address America’s jobs crisis. The $50 billion in new government spending on transportation and public works that he is now proposing is badly needed, and would eventually create jobs. But even in the unlikely event that the plan wins Congressional support, it will not be sufficient to stimulate enough growth to create the millions of new jobs the nation needs. Why has there been so little urgency in the White House to confront the issue that will most directly affect the outcome of the November elections?

Rarely has the job situation been more dire. Only once since World War II has the unemployment rate stood this high on Labor Day—during the steep recession of 1982 under President Reagan. It has remained at 9 percent or higher for 16 straight months and is likely to surpass the 19-month record of such high rates set in 1982 and 1983. When the rate includes those who have given up looking for jobs or are working part-time because they can’t find a full-time job, it is nearly 17 percent. Thus, one out of six Americans who want a job can’t find one today.

True, according to last week’s employment report, the nation’s private businesses created 67,000 jobs last month, more than almost anyone expected, and the fear of a double dip—back to back recessions—has been allayed. But it will take some 200,000 new jobs a month to absorb new entrants to the job market; that number will have to rise to some 300,000 a month to bring the unemployment rate down to its pre-recession level of 4.5 to 5.0 percent by 2013.

Nor are lost jobs the only problem. The Economic Policy Institute recently computed that the compensation of those who retained their jobs, including wages and job benefits, has also grown unusually slowly during the tepid economic recovery of the last year or so. In view of the fact that the income of a typical household was lower when George W. Bush left office than when he started, the very slow growth of wages during the economic recovery, when wages should grow rapidly, is punishing.

The unemployment rate has been so high for so long that some economists are now claiming there has been a significant structural change in the job market, and that the unemployment rate cannot fall to former low levels again. Too many Americans were trained for jobs that are now done overseas or are not qualified to fill new ones, they argue. These economists are saying that the economy will now reach a state of full employment with an unemployment rate of 6.5 percent to 7.5 percent, much higher than the 4.5 percent of 2006 and 2007; otherwise, the consequences will be higher wages and inflation.

But the economists are drawing dangerous conclusions from meager evidence, much of it anecdotal. If the job market were seriously tightening now, there would be some sign of renewed inflation and rapidly rising wages. There is none. For every job opening today, there are five Americans looking. And even if all 3 million current openings are filled, it will not come close to replacing the 8 million jobs lost in the recession.

In fact, there is a far simpler explanation for the slow job growth. The economic recovery has been too weak to generate enough new jobs. Without adequate sales, businesses are only beginning to hire again. Those who run companies are hesitating to invest as well, hoarding mountains of cash rather than looking for productive, innovative ways to use it.

Given the depth of the recession—the steepest since the Great Depression—the economy, with some help from stimulative government policies, should have roared back the way it did from other steep recessions in 1973-1975 and 1982. But the nation’s total income—Gross Domestic Product—is growing only about as fast as it did in the period following the far shallower recessions that ended in 1991 and 2001. And the private sector is now creating jobs at a similarly slow pace.

Obama’s $800 billion fiscal stimulus in spending and tax cuts, passed in early 2009, had a positive effect. It prevented a more serious recession, as the money was injected into the economy just in time to compensate for consumer cutbacks. But the stimulus faced new obstacles—namely, the enormous debt loads taken on in the 2000s to buy mortgages and support consumption. Now consumers are paying off debt and rebuilding savings, not spending freely. The nearly crippled financial community is far more cautious about lending to both consumers and business—the private mortgage market is just about moribund for now. And as Americans fail to find good jobs, they cut back spending still more.

Advertisement

Given such deterrents, slow job growth does not mean it is time to jump to conclusions about a radically altered job market. What is required is another round of substantial fiscal stimulus and new programs aimed directly at creating jobs. In early 2009, some economists urged more spending than Obama’s original $800 billion package. In my view, getting Congress to support the bill at the time was nevertheless a courageous political achievement. Several months later, however, the administration did not adjust to the disappointing circumstances as unemployment climbed rapidly. To create jobs, the Obama team should have put together a second stimulus package by mid-year, regardless of the political difficulties it would have faced.

At this point, if jobs are to be created in sufficient quantity, the economy needs another fiscal stimulus of several hundred billion dollars as well as still more aggressive loosening of monetary policy by the Federal Reserve. The Fed chairman has said the central bank may undertake such action, but according to press accounts, with the federal deficit around 10 percent of GDP, the administration is unlikely to announce the needed bold measures as Obama reveals more policy proposals this week.

Meanwhile there remain disturbing underlying factors that threaten the American worker. A relatively high dollar, for example, by making exports expensive, has persistently placed American manufacturers at a serious disadvantage and undermined the creation of good jobs. While foreign competition from nations with trained but lower paid work forces poses a threat, the high dollar has made matters worse than they needed to be. A persistent policy to lower the dollar against major trading partners would be useful.

Educational inequality continues to weaken America’s ability to compete as well, not to mention depriving too many young people of the opportunity to make a good living. And today, other nations are sending proportionally more young people to college than America does. This requires serious changes in policy.

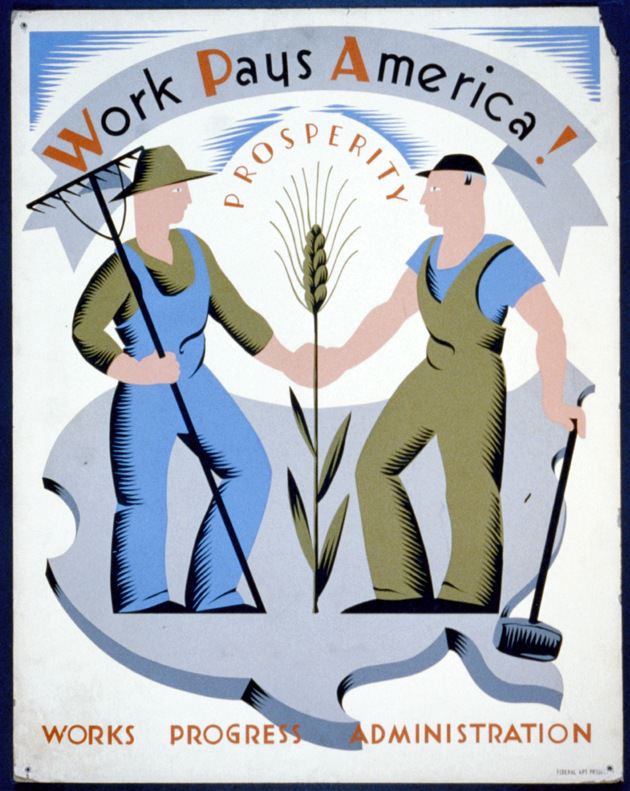

Aside from the new infrastructure plan, the administration is looking only to tax credits, mostly for small business, to create incentives for job creation. While useful, these will have a modest impact at best. Among the more pernicious consequences of lasting high unemployment is that workers begin to lose their skills and fail to develop new ones on the job. It is now time to consider a federal jobs project—an employer of last resort— like the successful programs of the 1930s.

The prospects for an immediate improvement in the labor market seem bleak: the nation will not get the fiscal stimulus required to put sufficient numbers of people back to work; in view of federal deficits, the administration and Congress are not likely to provide sufficient public investment to make the infrastructure bank a meaningful agent of change. Meanwhile, the longer people are out of work, the harder it is to employ them, and America will almost certainly not create a jobs program to hire them.

Without more immediate action, the lack of jobs in America is setting a stage for potential tragedy. Americans may not continue to tolerate such conditions as calmly as they now do. The rise of a broader populist backlash, of which the tea party is an early example, is increasingly possible.