When still in my early teens I decided that over the course of time I would see the ten highest mountains in the world. It did not occur to me that I would climb any of them, but I thought I could surely see them and even get to their bases. In 1967, I went to Nepal and managed to see seven of them; I even made it to the base of a couple, including Everest. But I missed Kanchenjunga, the third highest, which is in the far east of the country on the border with the Indian state of Sikkim. I also hadn’t seen K2, the second highest, which is on the border of Pakistan and China; or Nanga Parbat, the ninth highest, which is in the Pakistani Himalayas. To see these two I would have to get to Pakistan.

In 1968, I discovered that the Ford Foundation was sponsoring visiting professorships at the University of Islamabad. I knew the head of the theoretical physics department there, a man named Riazzudin (he used a single name). Various strings were pulled and I was appointed a visiting professor in Islamabad beginning in September of 1969. So far so good, but I had an additional idea. I was going to drive to Pakistan from Western Europe. After some research I decided that the only possible vehicle for this trip was a Land Rover Dormobile. This was a Land Rover that had been converted to sleep four and had a gas stove. I recruited my friends Claude Jaccoux, a mountaineering guide from Chamonix, and his then-wife Michéle, who had accompanied me to Nepal in 1967. Our plan was to leave from Chamonix the first week in September for what we thought would be a three-week drive. This would get me to Islamabad in time for the beginning of the fall semester.

On September 5 we passed through the recently completed, seven-mile tunnel into Italy under Mont Blanc. The following nights we were in Zagreb and then Skopje, which was just recovering from a terrible earthquake. From Skopje, we went through Greece to the Bosporus. We should have gotten to Istanbul at a reasonable time the next day but I had a fender bender with a truck driven by a man who was having an argument with his wife. In Istanbul, I found a Land Rover garage and we left the automobile there for three days while we explored the city. Then we crossed the Bosporus by ferryboat and were in Asia.

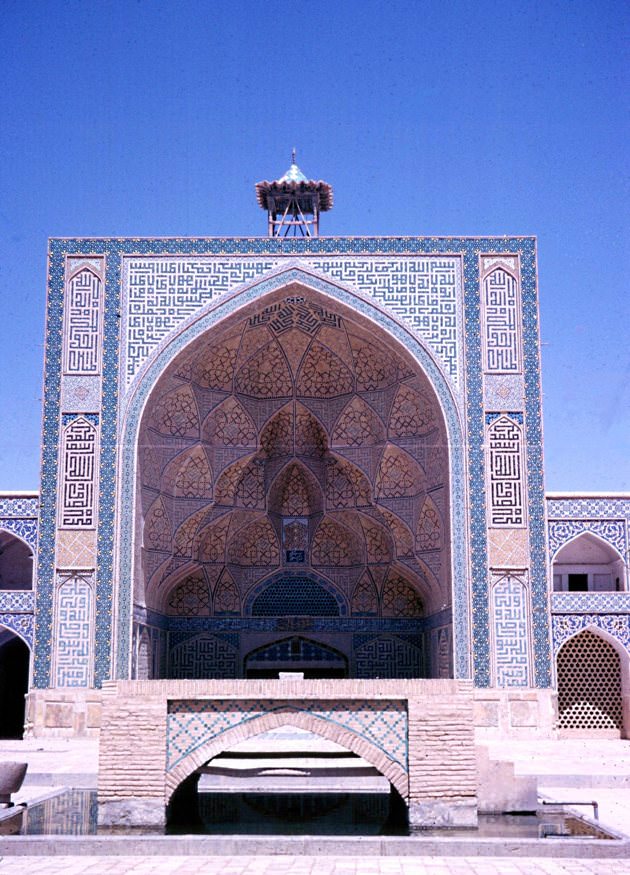

We spent our first night in eastern Turkey in Corum not far from the Black Sea, which we swam in the next day in the slightly wavy water, before continuing to Trabzon in Turkish Armenia on the Black Sea. It was part of the old silk route. Then Agri, a predominantly Kurdish town not far from the Iranian border. We passed Mount Ararat, which looked like it must have been a good port in a flood. We spent our first night in Iran in Tabriz and the next day was Tehran. We had now been on the road for two weeks and both we and the machine were a little shop worn. A couple of days in Tehran would do wonders for both. Tehran struck me as an incredibly busy place with touches of luxury here and there and many pictures of the Shah. While we were there, we visited Isfahan by commercial airliner to see the magnificent blue mosques.

Then we headed to the Afghan border stopping first at Gorgan, which was then a small town at the edge of a desert-like land we had to cross. Up to this point the roads had been pretty good. But the 700 miles from Tehran to the Afghan border were terrible. We had our first and only flat tire. A rock had put a substantial gash in it. The city of Mashad, where we spent the night, is a pilgrimage destination for Shiites, but we were in a hurry to get to the Afghan border, which we knew was going to be complicated to cross and was still a hundred miles away.

We had been warned about the red tape involved in crossing this border, and indeed it took hours. But then we were in for a surprise—a super highway of a kind that we had not seen since leaving Europe. The Russians and the Americans had been competing for hearts and minds by building sections of the highway. Part of it was named after President Eisenhower. There were even gas stations with pumps—unlike anything we had seen for many days. By the afternoon we were in Heart, which was then a lovely small town with a modern hotel built by the Russians. From here to Kandahar we had to cross another very hot desert. There were from time to time mirages, which looked like lakes and forests.

Advertisement

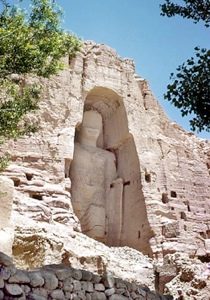

After stopping over in Kandahar, which seemed to be a very lively commercial city, we reached Kabul. We headed directly for what was then a brand-new Intercontinental Hotel where, after the variety of local cuisine we had been eating, we could get a western meal. From Kabul we made the very difficult drive to Bamiyan to see the gigantic rock carvings of the Buddha, which had been carved by anonymous Buddhist monks in the first half of the sixth century. These monumental sculptures revealed a remarkable fusion of Oriental and European traditions. The faces were Oriental but the clothing is Greek and Roman, reflecting the invasion of these civilizations that began with Alexander.

After spending time with the Buddhas we then made a very rugged forty-mile drive to the hanging lakes of Band-e-Amir. The lakes are set in craters above the valley and water spills over the top and irrigates the land below. It was hard to imagine a more beautiful place. We camped that night in the machine and were awakened the next day by the sound of a shepherd’s pipe. But then came the shock. The Land Rover would not start. No sound came from the ignition. I was wondering if we would ever get back to Kabul when Jaccoux had an inspiration. He looked at the battery. It was bone dry. We then remembered that we had some distilled water as part of our medical kit. Enough of it was emptied into the battery so that the engine started at once. I have never heard a more welcome sound.

From Kabul we headed east to the border with Pakistan. We arrived at the border station in Torkham in the early afternoon and crossed into Pakistan at the foot of the Khyber Pass. The pass was not too difficult to negotiate, although the surrounding country looked hostile and forbidding, both the people—all the men were armed—and the terrain. We headed at once for Peshawar and spent the night in the Dean’s Hotel, a Victorian establishment that featured cottages. Pakistan was dotted with traces of English colonial elegance. The next day we were in Rawalpindi, a typically overpopulated old Asian city to which Islamabad was a modern satellite. After 6,000 miles, we had made it to Pakistan. But we still hadn’t seen my mountains, which would require getting to remote parts of the North-West Frontier. That would occupy our next few weeks.

*

As I was writing this I had constantly to resist the temptation of pointing out how impossible all of this would be to do now—and maybe forever. It might well be possible to drive from France to Istanbul. Going through Anatolia in Eastern Turkey was dicey even then. We had been warned that the population was dangerous, and told never to travel by night and if we hit anything to keep on going. Jaccoux was actually armed with a pistol, which fortunately was never needed. Nothing need be said about Iran. The highway we traveled in Afghanistan is now mostly destroyed from decades of war and lack of maintenance. In 2001, the Taliban destroyed the statues at Bamiyan, a bit of cultural desecration that fills one with disgust. More recently cave paintings have been discovered and perhaps the outlines of another statue on the same site. The Khyber Pass is now the main supply route for the armies fighting in Afghanistan and the locals, who are sympathetic to the insurgency, extract large tolls. Peshawar, long since a base for the Pakistani Taliban and other jihadists in the tribal areas, has become so dangerous in recent years that many of its own residents have fled to the relative safety of Lahore and other cities. From the vantage point of 1969, it was difficult to imagine any of this.

This is the first installment of Jeremy Bernstein’s road trip to see the tallest mountains in the world. In the second installment, he recounts his experiences in the tribal areas of Pakistan’s North-West Frontier.