Why does it matter that the Russian parliament has just declared the Katyń mass murder of 1940 to be a Stalinist crime? Seventy years on, no one doubts the responsibility of Stalin, Beria, and the Soviet NKVD for the murder of about 21,892 Polish citizens in the Katyń Forest and four other sites. Yet, according to an opinion poll, more than 80 percent of Poles believe that the gesture, which confirms something that in effect all Poles already know, will improve relations between the two countries. Moscow understands that better relations with Warsaw will remove an obstacle to closer ties with the EU, and that for Poles history can be central to diplomacy.

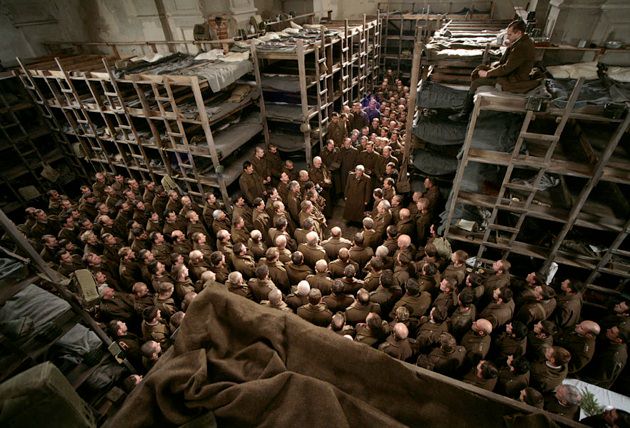

As Russian leaders have come to understand, for Poles Katyń is a special wound. Although discussions of Katyń usually refer to the Polish officers who were killed in the massacre, most of the victims were in fact reserve officers who as civilians worked as economists, doctors, lawyers, veterinarians and botanists and the like. The Katyń shootings were part of a Soviet attempt to reduce the Polish nation to a malleable social group by eliminating the upper classes. Between 1939 and 1941, when the USSR and Nazi Germany had jointly occupied Poland, Nazi Germany was pursuing a similar policy. German police forces sought, much like the Soviet NKVD, to destroy the Polish nation as a political entity.

Once Germany betrayed its Soviet ally in 1941, the war as most of us remember it began. That the true beginning of the war involved Soviet murder of men who had fought the Germans was awkward for all concerned. In 1943 the Germans uncovered the burial sites at Katyń. They immediately, and rightly in this one case, blamed the Soviets for the crime. The Soviets of course blamed the Germans, and expected their allies—the United States, Great Britain, the Polish government in exile—to go along. The Americans and the British, not wanting to antagonize their ally, preferred to accept the Soviet lie, and urged the Poles to do the same. This was too much for the Polish government to accept. Stalin then used Polish demands for a full accounting of the mass murder to break diplomatic relations.

The end of diplomatic relations between the USSR and Poland (both fighting together against Nazi Germany!) was a step towards the communist takeover of Poland. The Poles’ questioning of Stalin’s lie was used in Soviet propaganda to spread the idea that Polish émigré politicians were little better than fascists. The provisional government of Poland appointed by the Soviets naturally endorsed the Soviet version. For more than forty years thereafter, Poland’s communist regime upheld the falsehood that Katyń had been a German crime. This lie was told by the people who ruled, on behalf of the people in Moscow who ruled them. One of the great hopes of many of the men and women who led the peaceful Polish opposition to communism in the 1970s and 1980s was that the truth about Katyń might one day be told.

Since the fall of communism in 1989, Poles have been able to say what they like about Katyń, and now the basic facts of the matter are no longer in doubt. Yet many Poles believed that even after Poland joined the European Union in 2004, western allies failed to understand the particular cruelty of Katyń, and the more complex history of wartime suffering that it illustrates. The point is not just that Poles suffered more than most others during the war, although of course they did. The Holocaust, an event on an entirely different scale, often obscures this. A Polish Jew was fifteen times more likely to die during the war than was a non-Jewish Pole—but the latter was still about twenty times more likely to die than an American. The point is that acknowledgment of Katyń has not so far led to a reconsideration of the history of the war which would permit the observation that the Soviets were aggressors before they were liberators.

Any need, even the need for truth, is a vulnerability. Earlier this year, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin showed that he understood how a neighbor’s desire for historical reckoning can serve one’s own foreign policy. He began discussions about the massacre with Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk. Polish President Lech Kaczyński was preoccupied with historical memory, and perhaps concerned that Tusk, a political rival, was gaining an advantage by discussing Katyń. This led to his ill-fated flight from Warsaw on April 10, 2010 to commemorate the Polish dead at Katyń. Kaczyński’s plane crashed over a foggy military airport at Smolensk, killing him and the 95 others on board (including a dear friend of mine). This catastrophe reminded some of the Katyń crime: it killed members of the political elite, as well as family members of the victims of the mass murder of 1940.

Advertisement

Yet the Polish political class absorbed the blow, and a certain rapprochement with Russia continued. After the crash, Russian authorities published archival documents about Katyń on the internet and saw to it that Andrzej Wajda’s powerful film about Katyń was shown on Russian television. This was not only an expression of sympathy, it was the exploitation of an opportunity. Putin and Medvedev understand that Poland, acting within the European Union, can hinder Russian foreign policy. They also know that the discovery of vast shale gas reserves in Poland mean that Russia’s tried-and-true method of intimidating east Europeans by denying them gas supplies might no longer work in the near future.

The declaration of the Russian parliament deserves great praise, and the political acknowledgment of Katyń might affect Russia’s own discussions of Stalinism. It invites Poles into a conversation about history that heretofore has focused on Russia’s own wartime heroism and martyrology. Presumably, it won’t be long before a Russian or Polish historian points out that Stalin’s Great Terror, remembered as the great crime against Russians, in fact specifically targeted ethnic minorities such as Poles. However that may be, the declaration confirms a basic reality of our age of globalized commemoration: national history is becoming inseparable from foreign policy.