The first film by Frederick Wiseman I saw was Titicut Follies (1967). It was the fall of 1969, my freshman year of college, too long ago to trust my memory scene by scene. What I mainly remember is the festive mood in the dining-hall-turned-theater as the lights went down and latecomers ducked under the projector’s cone of bluish light as they made their way to sit with friends across the room. A very cool senior had made introductory remarks to the effect that what we were about to see had been “banned in Boston” (always promising), and I think we half-expected the local police to show up as if we had gathered in Rick’s gambling den in Casablanca (1942). I remember a little snickering during the opening pan across the expressionless faces of the inmates singing “Strike up the Band” while they wave—tentatively, almost spastically—their pompoms. But once the film started, there was only silence in the room, interrupted now and then by a gasp.

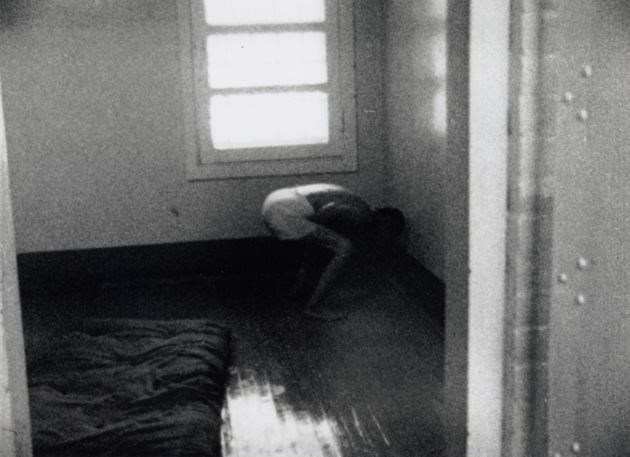

A few months ago, forty years older, I watched Titicut Follies on a DVD on my computer screen in my study at home. Memories of that first viewing came flooding back: the guards tormenting an inmate named Jim, marching him naked up and down the bright-lit hallways, peppering him with variations on one relentless question: “How’s that room, Jim? … You gonna keep that room clean, Jim? … How’s that room gonna be tomorrow, Jim? … How come it’s not clean today?” until he screams out his compliance in rage and helplessness. And then there was the German psychiatrist who looks for all the world like Hermann Goring, pestering an inmate with questions in a monotone voice about how often he masturbates. Did he feel guilty after raping his own child? “I need help but I don’t know where I can get it,” says the young man, handsome and fit, but with a deadness in his eyes. “You get it here, I guess,” says the doctor—help, as the rest of the film makes clear, in the form of lockdowns, hosings, strip searches, and assorted other humiliations.

Back in my college days everyone was reading R. D. Laing, father of the “anti-psychiatry” movement (The Politics of Experience [1967]), Thomas Szasz (The Myth of Mental Illness [1960]), and, soon to supersede them as an academic staple, Michel Foucault (Madness and Civilization [1961]), all of whom, in one way or another, attacked prevailing ideas of what was “normal” and what was “sick.” We were casually throwing around Erving Goffman’s phrase “total institution” to include schools and hospitals—as if the whole society were a gulag in which the real crazies were not the deviants or delinquents but the people in charge who deemed them so. We regarded Wiseman’s films—not only Titicut Follies but also High School (1968), Hospital (1969), and Basic Training (1971)—as advancing “the movement,” whatever, exactly, that was.

Yet however much Wiseman may have made the film in a spirit of outrage at how the patients—really inmates—were treated at Bridgewater State Hospital, he had invited us to a freak show. We were affluent late adolescents for whom it was impossible to think that the men on-screen had anything to do with us. We watched with a mixture of prurience and pity. The frequent frontal nudity—one of the pretexts for banning the film—gave us a frisson of sophistication as we pretended not to be shocked. Starting with the follies themselves, we were poised between laughter and horror as the guard, presiding as master of ceremonies, presents the chorus line as if he were doing an Ed Sullivan impression.

Watching the film today is an utterly different experience. I see images of Abu Ghraib. I see failed men exposed to mockery for having failed, men who once had families and jobs and respectable credentials, but, unable to manage their sexual or violent urges, descended into the pit into which any of us might fall. When I first saw the scene of Jim being shaved, I had not yet witnessed my father—who delighted me as a child by letting me watch him lather his face in the morning—lying prone in his final hospital bed, being shaved by a nurse not much more concerned with doing it thoroughly or gently than the barbering guard in the film was.

Upon a recent re-viewing of Wiseman’s next work, High School, about a large public school in Philadelphia, I felt the same disjunction between then and now. When it was first released, it gave my generation a view through the peephole at ourselves, or at least recent versions of ourselves. I remember feeling superior to the boys with soft mustache hair and not quite fully deepened voices. I remember the scene in which a teacher patrols the halls demanding a hall pass from every student he encounters—a squat little Nazi of whom Wiseman gives us the posterior view (not flattering) as the camera follows him from behind. The teachers, I recall, seemed to have been cut more or less from the same cloth as the Bridgewater guards—impatient and remote, going through the motions until closing hour.

Advertisement

But now that I’ve watched it as a teacher myself, it’s a different film. I feel for the teachers, all of them. I sense the pressure of the “counterculture” pushing from outside the school as they deliver sex-ed and deportment lessons while the students, seething at these surrogate parents yet frightened of their own impending freedom, sense that they are on the verge of a new world in which the old norms won’t apply. The teachers—though doubtless less reflective than those in Wiseman’s later film High School II (1994), about a charter school in Harlem—seem to be trying their best, as when one of them, Dr. Allen, explains to a student indignant over having been punished with a detention that to be a man means to prove “you can take orders.”

And then there is the poignant pair of scenes with the distraught father who comes to school to protest his daughter’s poor grades. Bursting out of a suit that might once have fit him, he seems to be wearing an emblem of his superannuation. A few scenes later, we see him at a college-counseling session with his daughter and wife, pushing back against the girl’s wish to go to cosmetology school instead of to a proper college. His anger sprays out in multiple directions: at the school for underestimating his daughter, at her for expecting so little of herself, and even, I think, at himself, for his failure to steer her toward the life he hopes for her—a hope, destructive as it may be, that arises out of love.

So I have changed. But so, I think, has Wiseman. Since the late 1960s, he has been making movies at a pace of roughly one per year—all the more astonishing since he typically shoots over a hundred hours to yield anywhere from ninety minutes in the final cut (Basic Training) to six hours (Near Death [1989]), sometimes spending more than a year in the editing room. “The shooting is the research,” he has said. He begins with no a priori story or point of view, but he disavows the term “cinema verité,” which he considers both specious and pretentious. He prefers “reality fiction”—a term that registers how much is shaped by the choices of what to shoot and how to put together what remains after the radical cutting. He uses no narrator, yet his aim is not to be objective but to be, to use the word he prefers, fair. In all these respects he has managed for more than forty years to be consistent without being redundant.

Yet he has become a more profound artist. It’s not so much that Wiseman has surpassed his early technique as that his pace and tone have changed. He lingers, savors; he has become more interested in aesthetic expression, both as a subject (notably in the two films about dance, Ballet [1995] and La Danse—Le Ballet de l’Opera de Paris [2009]) and as an aspiration for what he hopes to achieve through his own art. He has become a filmmaker less interested in exposé than in revelation.

The turn is evident, to my eye at least, in his beautiful film of 1999, Belfast, Maine, in which there is a palpable simultaneity of intimacy and loneliness—as expressed by a recurring shot of cars driving urgently at dusk past shuttered shops or darkened houses. We visit the nerve centers of the town: the courtroom, school, town hall, church, where we witness legal pleadings, an English class, a debate over tax assessments, prayers for the dying and the dead. In the interstices of these scenes we get fleeting images that have a shimmer of allegory: skewered fish wriggling in their death throes, a man pushing leaves off his lawn-as likely to win his battle against the wind as Sisyphus is to roll his stone over the hill.

One of the amazing effects of this film, despite the absence of conventional narrative and the extended length (more than four hours), is its considerable suspense. As we watch workers engaged in handicraft or automated labor, Wiseman has some fun with us: what on earth are they making? We visit fish- and potato-processing plants. Decapitated sardines travel down a conveyor belt to their ultimate destination in roll-top cans; potatoes are washed and steamed, the flesh scooped out and frozen en route to the supermarket as packaged patties topped with paprika. The machinery sputters and groans like antique tractors at a country fair. I suspect that future viewers will turn to this film as a documentary record of the United States in its late-industrial phase.

Advertisement

But Wiseman is not primarily a social commentator or an investigator of this or that institution, as he is often said to be. He is a portraitist, and his favorite genre is the double portrait. A visiting nurse washes the feet of a diabetic old man. A woman picks lice from another woman’s hair. In most such scenes—I am tempted to call them duets or pas de deux—one person occupies the subsidiary position (student, patient, novice, recruit) while the other (teacher, doctor, drill sergeant, nurse) holds the authority. In the early films, there can be cruelty in this relation, but in the later work Wiseman seems more interested in unarticulated tenderness, or what is sometimes called tough love.

Belfast, Maine includes two extraordinary instances of teaching inspired by love—love of the subject as well as of the learner. A young choirmaster speaks to his choristers about Bach and Palestrina, and suddenly we see in their faces that they understand the music in a new way. The high school teacher speaking to his students about Moby-Dick credits Melville with rendering ordinary fishermen—he knows he is speaking to the children of fishermen—as heroes capable of courage and grandeur. These are moving demonstrations of what genuine teaching can be, in a film where we meet many teachers: the nurses and social workers who treat the dying, but also the dying who teach the living what’s in store for them and how best to bear it.

Frederick Wiseman seems to me a great teacher himself. He not only shines light into places we are not meant to go, but he shows us anew places whose familiarity has made them obscure to us. In this sense he puts me in mind of Emerson’s remark that “the whole secret of the teacher’s force” is the power to “get the soul out of bed, out of her deep habitual sleep, out into God’s universe.” This image of the teacher as exasperated parent shaking awake the somnolent child and shooing him out the door captures for me what Wiseman is all about.

This post is drawn from the essay collection Frederick Wiseman, published by the Museum of Modern Art in conjunction with its film exhibition on the director’s work, which ends on December 17.