Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, opening this month in New York twenty-five years after its original release, is one of the great works of art of the twentieth century. As it begins, Simon Srebnik, a Polish Jew who was one of two survivors of Chełmno, returns to the death facility at Lanzmann’s request, and sings a song of his boyhood—about a white house, a house that is no longer—in the language of a country that was his homeland as it was of millions of Jews for centuries, a Poland made wretched by war. Mordechai Podchlebnik, the other survivor of Chełmno, in another conversation with Lanzmann, remembers human smoke against blue skies. The work of the stationary gas chambers began in German-occupied Poland on December 8, 1941. Here is the beginning of Lanzmann’s nine-hour reconstruction of the Holocaust, and in commencing with the faces and voices of Chełmno’s survivors, he has chosen well. Using no historical footage, Lanzmann instead elicits the detailed horror of mass death by asphyxiation at Chełmno, Bełżec, Sobibór, Treblinka, and Auschwitz from his own conversations with Jewish victims, German perpetrators, and Polish bystanders.

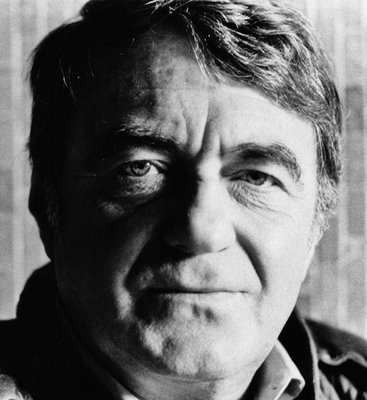

A quarter century ago, the Holocaust was not as widely recognized as it is today as an unprecedented evil. Lanzmann did much to change that. In his expansive “fiction of the real,” as he calls it, he is like a French realist novelist of the nineteenth century, addressing an injustice by painstaking research: a decade of reading; hundreds of risky conversations with victims, perpetrators, and bystanders; thousands of hours of unused film. This is “J’accuse” six million times over. Lanzmann is quite visible in the film, and heroically so. In his conversations with Jews and Germans and Poles, he is the perfect image of a French intellectual seeker of truth, doing what the existentialists spoke about but rarely did: imposing his mind and his will on a great emptiness, forcing it to take shape, and so leaving a trace of himself in history.

Lanzmann thereby helped to rescue the central event of the twentieth century from neglect. Yet his business is not history, or so he has always said. Marc Bloch, one of the greatest French historians, defined the goal of history as “understanding”; that historical comprehension of the Holocaust, in the sense of regarding its participants as human and grasping their constraints and motives, is just what Lanzmann rejects as impossible. Nevertheless, the film itself was a turning point in the history of the representation of the Holocaust, both as a source and as a model. In 1985 many survivors (and perpetrators, and witnesses) were still with us, despite the assurances to the contrary of President Reagan before his visit that year to Bitburg. Lanzmann had to find such people and induce them to speak—cajoling, insisting, intimidating them to say what they themselves regarded as unsayable. Now they are gone: Srebnik died in 2006, and we will never hear his song outside of this film.

Lanzmann’s aim was to bring the viewer into contact with the seemingly impossible, the unqualified nothingness of mass death, which he called, in a term that is inextricable from Sartre, “le néant.” During the last quarter century, libraries and archives have paid homage to his film by collecting or recording tens of thousands of video testimonies of Holocaust survivors. These are a precious record of individual lives and a valuable bulwark against forgetting, but they present difficulties as material for historians. Very few of them have been transcribed, and watching them all is simply impossible.

The leap to the visual has temporal costs for students of the Holocaust, of which the nine hours of Shoah are only a small taste; the written word has its advantages as a medium, and history (and so perhaps memory) depends upon it. Lanzmann’s marvelous work of research and selection leaves us with scenes around which the memory of the Holocaust has been framed: the former SS-man Franz Suchomel recalling Treblinka to the hidden camera, the calm mien of Treblinka survivor Richard Glazar as he describes the death facility, the Polish railway engineer Henryk Gawkowski’s gesture of a finger across the throat. The hundreds of thousands of hours of Holocaust video testimonies that we now have, precious though each of them is, are not arranged with such artistry and will never be edited with such skill. It is to be hoped that a benefactor will appear who will fund a team of historians, translators, and lawyers to select, transcribe and annotate some of this priceless material. This would add much to the value of the indexes and finding aides already compiled with much labor.

In Shoah, Lanzmann pays tribute to history in his conversations with Raul Hilberg, the man who wrote the first serious scholarly study of the Holocaust. We are reminded, watching Hilberg speak, of his heroic empiricism, his ability to confirm mass killing on the basis (for example) of records of one-way conveyance by rail. Yet between the scholarship of an extremely cautious institutional historian such as Hilberg and Lanzmann’s visual reconstruction of the Holocaust lies a world of valuable written material about the lives and deaths of Jews—much of it, twenty-five years later, still little used. This owes not least to Hilberg’s own skepticism about the reliability of survivor testimonies. Thanks in part to the powerful intimacy of Shoah, Lanzmann’s assumption is now widespread: we know what we need to know of the Holocaust, but we need help to “see” or “experience” it, in order to best identify with its victims. Yet the clearest records of the victims are often written documents produced by survivors during or after the war, such as those at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

Advertisement

Viewers’ identification with the Jewish victims of the Holocaust was not at all something Lanzmann could take for granted in 1985. Through unbearable conversations about unthinkable horror, such as his conversations with a Jewish barber who cut the hair of naked Jewish women just before they were gassed, he brings the viewer into seemingly unambiguous emotional contact with Jews, in this way acclimating us to the Holocaust while denying that it can be understood. The Jews with whom Lanzmann speaks are, sadly, exceptional; the main victims of the Holocaust were those millions of Jews who were killed. In the film the small number of tragic survivors help bring us into contact with the millions of tragic dead, their families and friends. Would the victims have wanted for us to identify with them? More likely, as Auschwitz survivor Filip Müller suggests, they would have wanted us to help them. Identification and solidarity are perhaps related, but they are not quite the same thing.

Now that we take for granted that most people feel sympathy with the Jewish victims of the Holocaust, we might ask how far this truly brings us to some moral understanding of the tragedy itself. Perhaps it would make more sense, at least as a thought experiment, for those of us who were not in fact victims to also try to identify with the bystanders? Bystanding is what people generally do at times of moral need, and is thus the moral risk that we have confronted ever since the Holocaust. Lanzmann makes such an alternative experience of the film impossible: this is its demagogic appeal and substantive weakness. The chief bystanders in Shoah are toothless, uneducated, anti-Semitic Polish peasants, names absent or misspelled, impossible objects of identification.

The traditional objection to this portrayal of Jews’ Polish neighbors is that Lanzmann should have included conversations with Polish rescuers or with Polish Jews who survived the war and remained in Poland. But Lanzmann wanted to make an important point about the continuity of Christian anti-Semitism after and despite the Holocaust, and he makes it well: fair enough. There is an undeniable moral and aesthetic power to the scenes in which Polish peasants reveal their anti-Semitic understanding of the world in their very descriptions of the Holocaust: as a catastrophe brought down on Jews by the Jews themselves. But how does Lanzmann direct this power? He flatters us with it, unmistakably separating the western allies from a barbarous Polish countryside where such things as death facilities could be erected (Lanzmann has denied that such a thing could happen in France). It would perhaps be hard, today, for a French intellectual to make such a film about the Holocaust without mentioning, for example, the notorious roundup of Paris Jews by French policemen at the Vel d’Hiv in 1942.

Lanzmann does speak with one Pole, the famous wartime courier Jan Karski, who figures as a civilized man of the West. In 1942, Karski slipped into the Warsaw ghetto, spoke to Jews, and came to understand the Holocaust. But Lanzmann does not have Karski discuss what happened next. Karski left the ghetto, made his way (no small undertaking) to London and Washington, and told leaders about the Holocaust. There was no meaningful reaction, in part because almost no one, in those anti-Semitic times, was interested in fighting a war for the Jews, or in being seen to do so. Karski is in the film to introduce the Warsaw ghetto, but his mission from its Jews to describe their fate to the West is left out. If Lanzmann had included it, we might then have to see our countries, in some limited but nevertheless significant measure, as among the bystanders. When we identify with victims, we believe we see ourselves, but perhaps we are simply looking away.

Advertisement

Shoah is playing in New York City at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas and, beginning on December 24, at the IFC. It will be screened nationally in 2011.