More than five years after Danish artist Kurt Westergaard published controversial cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, lives continue to be lost and—if we are to believe the police and intelligence agencies of dozens of countries—assassinations are still being attempted and plotted because Muslims have been angered by the display of such images. In December, a suicide bomber inspired by other insulting drawings of Muhammad attacked a busy shopping street in Stockholm; on Friday, a court in Copenhagen sentenced a Somali man to nine years in prison for attempting to kill Westergaard.

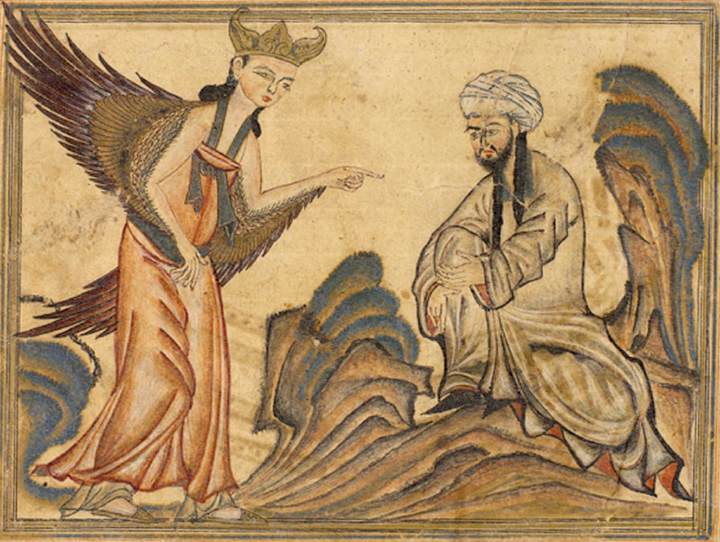

Traditional Islamic doctrine offers little explanation for this violent response. There is no explicit ban on figurative art in the Quran, and representations of Muhammad, though absent from public spaces, appear in illuminated manuscripts up until the seventeenth century; they still feature in the popular iconography of Shiism, where antipathy to pictures of the Prophet is much less prevalent. There are numerous such depictions—faceless or veiled as an indication of his holiness, or even depicted with facial features—in manuscript collections. It is only quite recently that Muslims living in the west have begun lodging objections to the reproduction of these images in books. The objections are by no means confined to a militant fringe. Populist sentiment—fuelled by the Salafist or “fundamentalist” trends emanating from the Gulf and Saudi Arabia, has produced a near consensus among a majority of Muslims that representations of the Prophet and other holy figures are forbidden by Islam.

All the more puzzling, the recent iconophobia in popular Islam has largely ignored the spread of such images on the Web. Indeed, all the images that have been cited in the cartoons controversy are readily accessible online, including Westergaard’s notorious cartoon published by the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten depicting Muhammad with a bomb in his turban, and a more recent one by Swedish artist Lars Vilks showing him as a dog, modeled on the canine sculptures that since 2006 have been installed on Swedish traffic circles.

What has been missed in the recent upheaval is that Muslim piety and Muslim militancy have been at odds. Salafists yearning for a return to the “pure Islam” of the Prophet’s era are not necessarily the same as those seeking holy war against western influences, though there may be some overlap between the two. The pious Salafist response is exemplified by Abdul Haqq Baker, imam of the Brixton Mosque in London, who says that believers should avert their gaze from blasphemous images and desist from showing them around. The militants or jihadists have taken the opposite view, using the web to publicize the images while making threats against artists and publishers who dare to display them in a public gallery or on a printed page.

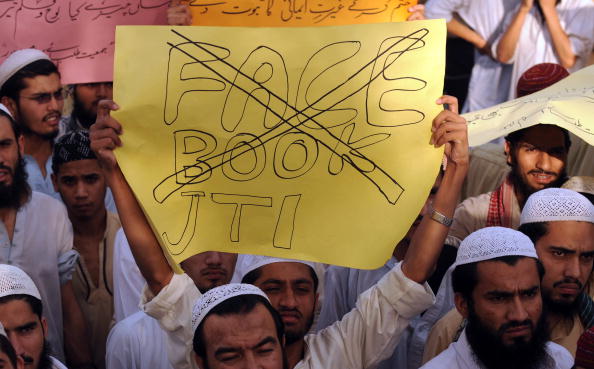

Policing the web is nearly impossible. In Pakistan and Bangladesh governments blocked access to the Internet after a Facebook group launched an “Everyone Draw Mohammed Day” last May. But the results were only local and temporary. Elsewhere, Islamic militants have launched cyber-attacks by hacking into computers, including Jyllands-Posten and Vilks’s personal website, but also others many with no connections to either. Danish victims of cyber-attacks in early 2006 included websites belonging to Girl Guide troops, school districts, private companies, and nursery schools, as well as the websites of government departments—part of a campaign of punitive actions against Danish institutions generally. Despite—or rather, because of—the furor, the images remain highly accessible.

This contradiction suggests a somewhat archaic and formalistic approach to the tools of communication and what constitutes private and public space. In a departure from the medieval conventions, the paper and ink of Marshall McLuhan’s Gutenberg Galaxy are now seen as vehicles of public expression: the shock provoked by a visual insult printed on the page of a journal or exhibited in public can easily be exploited by militants. Yet when the same images (or worse) appear on the Internet, any action aimed at protecting religious sensibilities will be thwarted because websites are often hosted anonymously and thus extremely difficult to shut down.

The self-appointed defenders of Islamic honor may seek redress or revenge by threatening artists and publishers, but thanks to the combined effects of television and the Internet, the main outcome of their efforts has been a quantum leap in the dissemination of the images pious Muslims find most offensive. By drawing attention to them the militants become accessories to the blasphemies they ostensibly seek to repress.

This comes as no surprise in an era of religious militancy in which the charge of blasphemy is used as a means of political arousal rather than a legal resource for defending the sacred. In Pakistan Salman Taseer, governor of the Punjab region, was assassinated in January, for daring to suggest that the country’s blasphemy laws, which human rights activists claim are routinely abused to persecute minorities or settle personal or family scores, should be abolished. Even in America, conservative and evangelical groups have objected to art works that challenge traditional notions of the sacred by using religious iconography in novel ways, thereby alerting the attention of philistine zealots. Examples include Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ (an image of a crucifix submerged in what appears to be urine) and Chris Ofili’s Holy Virgin Mary, with its image of an African Madonna crafted from the author’s trade-mark use of paint and elephant dung, with cherub-like images of female genitalia. Serrano received death threats, and in the Brooklyn Museum of Art, Ofili’s painting needed an armed guard and Perspex screen to protect it, after high-profile critics including Mayor Giuliani attacked the museum for showing it. Questioning received notions of the sacred is always dangerous.

Advertisement

The original controversy over the Muhammad cartoons arose in September 2005, when Jyllands-Posten published a number of images intended to satirize Islamic extremism, including Westergaard’s notorious caricature of Muhammad. A script on the turban displays in Arabic the shahada—the Islamic declaration of faith (“there is no god but Allah, Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah”). While Westergaard explained that he intended merely to call attention to the exploitation of Islam by terrorists and militants, the image could be taken to imply that Islam is in itself a religion of violence or a “terrorist faith.” Protests by Danish imams, spearheaded by one with an ultra-conservative Salafist background in Saudi Arabia, produced no results in Denmark, where freedom of speech is regarded as a fundamental right. The affair escalated after Muslim governments and inter-governmental organizations, whose legitimacy depends on being seen to protect the rights of Muslims, became involved.

The Danish imams took the offending images to Cairo and other Middle East capitals. The dossier included an image of Muhammad as a pedophile downloaded from a Christian evangelical website and a picture of a man wearing a pig-faced mask taken at a French food festival with no Islamic connections, neither of which had been published by Jyllands-Posten. The dossier was circulated by the Arab League, and at a special meeting in Mecca of the Organization of the Islamic Conference—an umbrella body comprising fifty-seven Islamic states and Muslim countries. The OIC passed a resolution condemning the insult to the Prophet and the use of freedom of expression as “a pretext to defame religions.”

At least 200 people—most of them Muslims —died in anti-Danish and more generally anti-Western and anti-Christian protests in various Muslim countries where the cartoons were republished (in a minority of cases), or as a result of television and press reports. Some were killed by police trying to control the demonstrations, others—as in the case of Nigeria—in clashes between Muslim and Christian mobs that broke out after demonstrations against the cartoons. In the Middle East a commercial boycott led to the removal of Danish goods from supermarket shelves: Arla Foods, one of the larger companies, estimated its losses in 2006 at $223 million. Danish embassies and consulates were attacked and burned in Syria, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Indonesia.

After Yousuf al-Qaradawi, the Muslim Brotherhood preacher and host of a popular show on al-Jazeera television, called in February 2006 for a public “day of rage” against the cartoons, the riots escalated into generalized attacks on Western targets. To add fat to the fire, there were reports that Danish Neo-Nazis, in implicit collaboration with Muslim activists, were planning a public burning of the Quran (although in the event they were intercepted by Danish police). In Damascus, protestors torched the Norwegian as well as the Danish missions. And in Libya, where demonstrators stormed an Italian consulate, at least nine people died.

Despite public statements by the US government scolding the Danes for failing to respect religious sentiments, even American franchises such as Holiday Inn, Kentucky Fried Chicken, Pizza Hut, and McDonald’s were sacked or torched in Pakistan. What one Jyllands-Posten journalist had jauntily described as an exercise in “democratic electro-shock therapy” for Islamists had snowballed into a major international crisis.

The turmoil appeared to subside after the paper’s editor-in-chief issued an apology. (According to a cable released by WikiLeaks, under pressure from the United States and the Danish government, the paper also decided against republishing the cartoons on the first anniversary of the controversy, averting, as the US ambassador put it, “another potential crisis.”) But a new report from Stratfor, a private intelligence agency based in Austin, Texas, states that “the dust kicked up over the cartoon issue” is far from settled and is unlikely to be so soon. While working on its forecasts for 2011 the organization was struck by the number of recent plots involving the cartoon controversy, with groups such as al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula going to great lengths to keep the “topic burning in the consciousness of radical Islamists, whether they are lone wolves or part of an organized jihadist group.” There have been several attempts on the life of Kurt Westergaard and his wife, including by the Somali, said to be associated with the al-Shabbab group, who has just been convicted in Copenhagen. (In January, 2010, he broke into Westergaard’s home, and was shot and wounded by Danish police while pursuing the artist with an axe.)

Advertisement

The most recent of several terrorist plots described by Stratfor came to light on December 29, when police in Denmark and Sweden arrested five men with a variety of ties to Iraq, Lebanon, and Tunisia. The men were allegedly planning an armed assault on the offices of Jylland-Posten in Copenhagen and were said to have obtained a pistol and submachine gun equipped with a sound suppressor, and to possess flexible handcuffs—indicating that they intended to take hostages in a theatrical operation.

Other recent plots involving depictions of Muhammad include the March 2010 arrest in Ireland of seven people with Middle Eastern and North African backgrounds, in connection with an alleged plot to kill Lars Vilks, the Swedish artist who depicted Muhammad as a traffic-circle, or “roundabout,” dog. An American woman, Colleen LaRose—known by her on-line alias “Jihad Jane” was arrested by the FBI on returning to the US from Ireland in November. In early February, she pleaded guilty to a series of federal charges that included a plot to kill Vilks. It appears that her meetings in Ireland with the would-be assassins, whom she met through Internet chat-rooms, were monitored and watched by the FBI and Irish police.

One of the most alarming attacks so far connected with the cartoon controversy was the suicide-bombing in Stockholm on December 11 by Taimour Abdulwahab, an Iraqi-born Swedish citizen. (Fortunately the attack, which could have been devastating, was frustrated when his explosives went off prematurely, killing only himself.) In an e-mail sent to the Swedish News Agency shortly before his attempted atrocity, Abdulwahab referred explicitly to Vilks’s pictures, as well as to the presence of Swedish troops in Afghanistan.

The Stratfor report reveals the risks to which named artists who have dared to lampoon Muhammad have exposed themselves, raising difficult questions for editors torn between the fear of Muslim reprisals, and accusations of pandering to extremist prejudices. In November 2009, Yale University Press published The Cartoons that Shook the World, the definitive account of the controversy by Jytte Klausen, a Danish-born scholar of contemporary Islam who teaches at Brandeis University. Shortly before the book’s appearance the Press decided to remove all the images of Muhammad, including not only the cartoons, but such well-known historical images as an engraving from Gustav Doré’s version of Dante’s Divine Comedy depicting the punishment of Muhammad in the Eighth Circle of Hell.

The publisher defended its decision stating that “all” the authorities it had consulted had voiced “serious fears” that republication of the images would provoke more violence. But this was challenged by at least one consultant, the distinguished Islamic art historian Sheila Blair, who told the London Guardian that she had “strongly urged” the press to print the images. Suppressing them, she said, would “distort the historical record and bow to the biased view of some modern zealots who would deny that others at other times and places perceived and illustrated Muhammad in different ways.” In response to the Yale decision, Gary Hull, a professor at Duke University, has printed all the discarded images in Muhammad: The Banned Images, an illustrated book published by the Voltaire Press, which he founded for this purpose. The book, which is available on Amazon, can be downloaded on Kindle. Amazon has not been intimidated, and nor has Wikipedia, which has numerous entries on the controversy that include—as Yale could have pointed out—all the cartoons as well as numerous depictions of Muhammad from the historical repertory.

In 2008, Muslims protesting against the illustrations in a Wikipedia entry on Muhammad claimed to have collected nearly half a million signatures for an online petition objecting to the reproduction of an image of Muhammad taken from a seventeenth-century copy of a fourteenth-century Persian manuscript. Wikipedia rejected a compromise that would allow visitors to choose whether to view the pages, stating that it does not censor itself for the benefit of any one group.

While it may be true that traditional notions of free speech or expression, as displayed in material media such as paint, ink, canvas, and paper are under threat from militants insistent on denying the variegated richness of the Islamic artistic heritage, the dangers should not be exaggerated. The electronic word and image are not easily suppressed—especially if authors and artists choose to remain anonymous. The liveliest depictions of Muhammad currently available are on the “Jesus and Mo” website, an online comic strip about religion that has until now attracted little criticism or vitriol: no artist signature, no terrorist target.