It’s not easy to make sense of the remarkable Lod Mosaic, a large, ancient floor newly discovered in Israel and now on display in the United States for the first time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. But the very difficulty of interpretation, together with the excellent state of preservation, is what makes it so fascinating. We simply don’t know whether it was part of a residence or an official building, and we can’t even say whether the owner or owners were Jewish, Christian, or pagan. The date is not secure either, although the excavator proposes about AD 300 because late third-and-fourth-century coins and ceramic scraps were found immediately above it. Miraculously, what is on display at the Met survived intact apart from one large gash near the bottom that the excavator considers ancient damage, although not everyone agrees.

The mosaic at the Met is the main part of an ensemble of floor mosaics that the Israeli Antiquities Authority uncovered in 1996 at Lod (ancient Lydda) during the construction of a road between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. (The other fragments from the same floor have not come to the United States but can be viewed online.) Measuring some twenty-three and a half feet by thirteen feet, the mosaic consists of a large square containing a central octagonal medallion, with narrow rectangular panels above and below the square.

The upper panel consists largely of predatory animals in savage encounters with one another, as for example a tiger ferociously biting a horse and a snake attacking a fish, although a handsome peacock showing off its plumage is a startling exception to the violence.

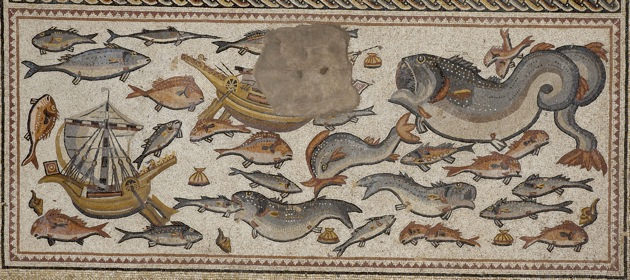

The lower panel includes two ships, one under sail and another not (in the damaged part). There are also menacing sea creatures, of which one seems to be a fantastic whale, and assorted small fish.

The large square in the center depicts mostly benevolent animals, apart from a lion on top of a deer in what looks like a mutually consensual act rather than an assault, and a gazelle that may be losing some blood. The overall impression is distinctly more serene than in the upper and lower frames.

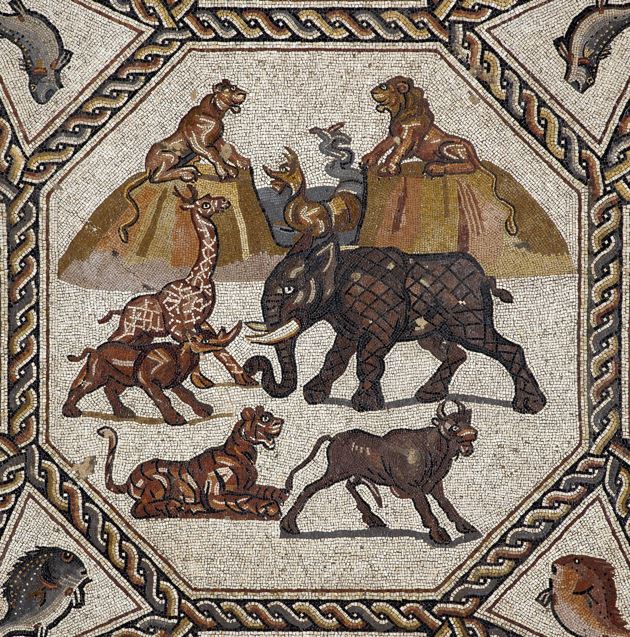

But it is the octagonal medallion occupying the center of the floor that is most arresting, with a mix of exotic beasts that looks like a zoo by the edge of the sea. An elephant, rhinoceros, giraffe, lion, and tiger appear to be enjoying one another’s company, while two lions straight out of Julie Taymor’s repertoire guard a passage to the open sea, where a Disney-like monster is cavorting in the waves.

Miriam Avissar, the archaeologist who discovered the mosaic, thought that the exotic animals might allude to public spectacles in regional amphitheaters, where such creatures could occasionally be seen. But I believe that the most telling item in the whole mosaic is the large vase at the bottom of the central section, with panthers poised on either side in apparent contemplation of one another’s faces.

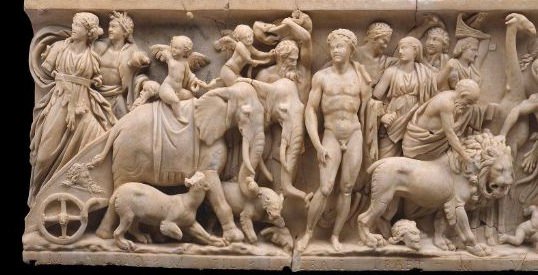

Though rare in ancient art, this scene has three astonishing parallels. All are large vessels with side handles in the form of panthers, just as they appear on the mosaic. A great marble vase (krater) with crouching panthers on either side forming handles was found in the Byzantine church at Petra, where it can now be seen in the main museum on the site, but it is of a much earlier date than the church itself. A marble basin now in the Gardner Museum in Boston also has similar panther handles, and on a sarcophagus frieze at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston a Dionysiac procession shows a satyr carrying a drinking cup with identical handles.

These three pieces, all from the late second or early third century, are the chief examples of such vessels, although objects of this kind are also depicted on lamps from Italian workshops, and two late antique gold cups with panther handles have turned up in Romania. The presence of analogous animal imagery on the Boston sarcophagus relief—its procession includes a giraffe, elephants, and a lion—would tend to confirm the suggestion made by the Met’s curator, Christopher Lightfoot that there seem to be traces of Dionysiac imagery in the mosaic.

It’s true that normally antagonistic animals were famous for consorting together in Dionysus’ company, exactly as the Boston sarcophagus shows.

In late antiquity, the Greek epic poet of Dionysus, Nonnos of Panopolis, waxed eloquent in complex verse about the comity of the god’s animals:

The lion in playful sport pressed his mouth gently on the bull’s neck… The spotted panther leaping on high with bounding feet capered toward the hare. The wolf let out a triumphal howl from a merry throat and kissed the sheep with jaws that tore not. The bear lifted her forefeet and threw them round the heifer’s neck, embracing her with a bond that did no hurt. The calf bending again and again in sport her rounded head, skipped up and licked the lioness’s body… The serpent touched the friendly tusks of the elephant.

Yet there is no trace on the Lod Mosaic either of Dionysus himself or of any other god—or, for that matter, of any human. What seems to me much more interesting is a little-studied mosaic from Daphne, near Syrian Antioch, now in the Baltimore Museum, which depicts pairs of animals that would normally be enemies facing one another in a non-confrontational, indeed positively friendly way. This scene was definitively explained decades ago by a text that appears on a comparable mosaic from Jordan: “The lion will eat straw like the ox,” which is a quotation from the famous prophecy of the peaceable kingdom in Isaiah.

The central medallion at Lod could possibly be another glimpse of the peaceable kingdom, and the surprising appearance of the panthers on the drinking krater may be somehow connected with the transmutation of Dionysiac motifs in the representation of Isaiah’s prophecy. But the frustrating thing is that, even though the connection to Isaiah would rule out a pagan context for the mosaic, it would leave completely open the possibility of both a Jewish and a Christian one. In either case, looking at the mosaic is so satisfying that one can live with this uncertainty, just as I imagine the residents of ancient Lydda did at a time when the religions of the region, including polytheist ones, borrowed freely from each other’s images and cohabited, for a while, in peace.

The Lod Mosaic is on view until April 3 in the Shelby White and Leon Levy gallery of Hellenistic and Roman art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It will be then be shown at the Legion of Honor Museum in San Francisco, the Field Museum in Chicago, and the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio, before returning to Israel, where a new museum is being constructed to house it in Lod.