Twenty-five years ago, Art Spiegelman published the first of his Maus books—a pair of graphic novels about the experiences of the author’s father during the Holocaust, with Jews drawn as wide-eyed mice and Nazis as menacing cats. Maus II was awarded the Pulitzer prize in 1991—the only graphic novel ever to win—and both books continue to move and provoke readers. In his new book MetaMaus, Spiegelman talks with Hillary Chute, a professor of English at the University of Chicago, about how the Maus books came into being. What follows is the first of two excerpts from their conversation.

—The Editors

Hillary Chute: So…how did you come across the idea of drawing mice, anyway?

Art Spiegelman: Ah, mice…

Actually, it all started with me trying to draw black folks. In 1971, when I was twenty-three, I was part of an extended community of underground comix artists centered in San Francisco, that had come together in the late ’60s in the wake of R. Crumb’s Zap Comix. A cartoonist pal, Justin Green, was put in charge of getting together a comic book called Funny Aminals.

I wanted to do something in that melodramatic pulp illustration mode, complete with venetian blind shadows, but with animal faces in which the denouement would have the protagonist getting crushed to death by a giant mousetrap that snaps shut on his body. I made some sketches but I was floundering. A filmmaker I had become close friends with, Ken Jacobs, was teaching an introduction to cinema class. On this particular day, Ken showed a bunch of old racist animated cartoons from the silent and early sound era. The blacks were cheerfully represented as subhuman, monkeylike creatures with giant minstrel lips—stereotypes stealing chickens, stealing watermelons, playing dice, all singin’ & dancin’, just the daily stock in trade of our racist cartoon heritage.

…it all led me to my Eureka moment: the notion that I could do a strip about the black experience in America, using an animated cartoon style. I could draw Ku Klux Kats and an underground railroad and some story about racism in America.

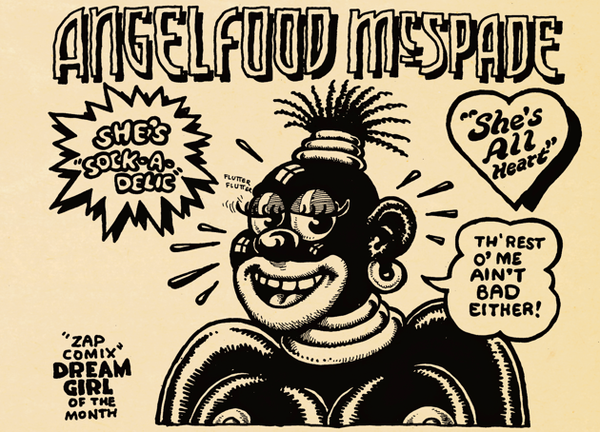

That seemed really exciting for a couple of days until I realized that it could be received as one more example of the trope that Crumb had consistently mined with Angelfood McSpade and other willful racist caricatures: the return of the repressed—all that insulting imagery that had been flushed out of the mainstream culture but existed in the back of everybody’s lizard brain—now brought back in a kind of Lenny Bruce “Is there anybody I haven’t insulted yet?” spirit, with the hope that if you say the word “nigger” over and over again, you remove its sting…

After my self-excoriating doubts settled in, I realized that this cat-mouse metaphor of oppression could actually apply to my more immediate experience. This development took me by surprise—my own childhood was not a subject for me. But I did realize that if I shifted from Ku Klux Kats and anthropomorphized “darkies” to the terrain I was more viscerally affected by, the Nazis chasing Jews as they had in my childhood nightmares, I was on to something. It became my three-page contribution to Funny Aminals.

You’ve said that Hitler was your collaborator on Maus. When did you become aware of the history of anti-Semitic caricature and stereotypes in creating your animals?

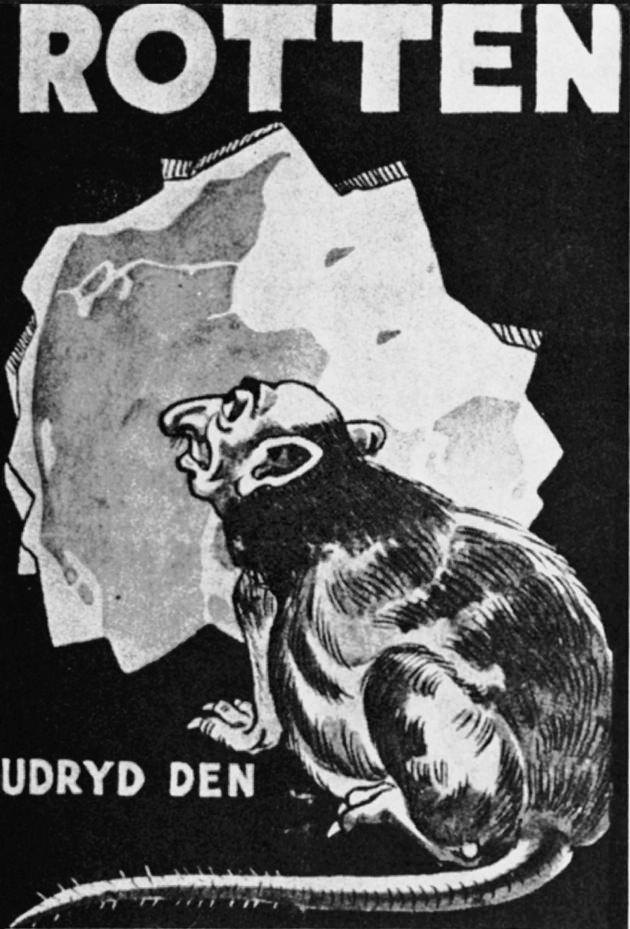

I began to read what I could about the Nazi genocide, which really was very easy because there was actually rather little available in English. The most shockingly relevant anti-Semitic work I found was The Eternal Jew, a 1940 German “documentary” that portrayed Jews in a ghetto swarming in tight quarters, bearded caftaned creatures, and then a cut to Jews as mice—or rather rats—swarming in a sewer, with a title card that said “Jews are the rats” or the “vermin of mankind.” This made it clear to me that this dehumanization was at the very heart of the killing project.

In fact, Zyklon B, the gas used in Auschwitz and elsewhere as the killing agent, was a pesticide manufactured to kill vermin—like fleas and roaches.

As I began to do more detailed and more finely grained research for the longer Maus project, I found how regularly Jews were represented literally as rats. Caricatures by Fips (the pen name of Philippe Rupprecht) filled the pages of Der Stürmer; grubby, swarthy, Jewish apelike creatures in one drawing, ratlike creatures in the next. Posters of killing the vermin and making them flee were part of the overarching metaphor. It’s amazing how often the image still comes up in anti-Semitic cartoons in Arab countries today.

Advertisement

How did you decide on the visual surface for Maus?

One thing I tried out was scratchboard illustration that reminded me of Eastern European children’s book illustration. It was interesting, but really stopped the flow of storytelling dead in its tracks. First, it insisted on my superiority to the reader, in the sense of, “I have a certain expertise at making this thing that looks like wood engravings that you don’t have, so shut up and listen.” It had the authority of looking labor intensive, but each box in that approach led to one slowing down to look at that box as a drawing—it interfered with the process of actually reading comics where one would glean the visual information necessary and march forward toward another picture.

There was one rendering of a cat in full Nazi drag that looked sort of like Marlon Brando in The Young Lions. It was the most noble and savage version of the Nazis, tying into the stereotypes that presented Nazis as somehow sexy. It reminded me of the whole Night Porter genre of pornography that involved SS uniforms and scared me away from drawing Maus with really large-scale cats.

You show mice with their mouths open so few times in the book. Was that deliberate?

When I show the mouths, they’re almost always there as cries and screams. It’s not usually used to show characters yukking it up and laughing really loud. It’s that triangle inverted as you look at it from underneath with a kind of scream face. It allows for a kind of vulnerability, coming in toward the underbelly of the mouse. The screaming mouth completes the face; it’s a way of making that face human.

MetaMaus, by Art Spiegelman, has just been published.