In the spring of 1980, I began to photograph the New York subway system. Before beginning this project, I was devoting most of my time to commissioned assignments and to writing and producing a feature film based on Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novel, Enemies, A Love Story. When the final option expired on the film, I felt the need to return to my still photography—to my roots.

I began to photograph the traffic islands that line Broadway. These oases of grass, trees, and earth surrounded by heavy city traffic have always interested me. I found myself photographing the lonely widows, vagrant winos, and solemn old men who line the benches on these concrete islands of Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

I traveled to other parts of the city, from Coney Island to the Bronx Zoo. I revisited the Lower East Side cafeteria where I’d photographed several years before. The cafeteria was a haven for the elderly Jewish people surviving the decaying nearby neighborhoods. I photographed the people I had known there, survivors from the war and the death camps who had clung together after the Holocaust to re-root themselves in this strange land. I walked along Essex Street to visit an old scribe who repaired faded Hebrew characters on sacred Torah scrolls. He and his wife, both survivors of Dachau, worked together in their small religious bookstore. Occasionally, he’d allow me to take a photograph as he bent over the parchment with his pen. When the flash went off, he would wave me away. I would return later with prints that he put into a drawer, carefully, without looking at them. Sometimes, returning from his shop during the evening rush hour, I would see the packed cars of the subway as cattle cars, filled with people, each face staring or withdrawn with the fear of its unknown destiny.

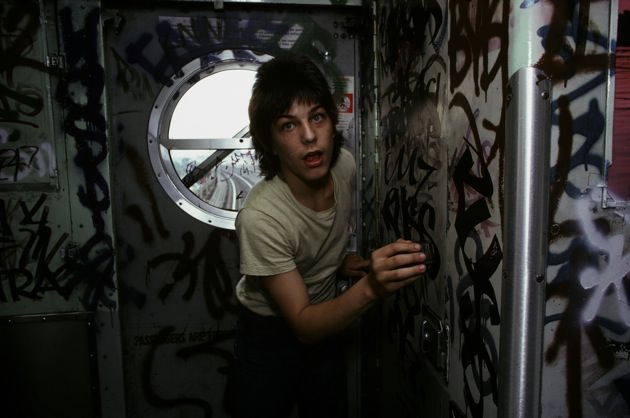

The subway interior was defaced with a secret handwriting that covered the walls, windows, and maps. I began to imagine that these signatures surrounding the passengers were ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. Every now and then, when I was looking at one of these cryptic messages, someone would come and sit in front of it, and I would feel as if the message had been decoded. I started to draw a connection between the Broadway islands, the neighborhood cafeteria, and the pious scribe on the Lower East Side. The connection was the subway.

To prepare myself for the subway, I started a crash diet, a military fitness exercise program, and early every morning I jogged in the park. I knew I would need to train like an athlete to be physically able to carry my heavy camera equipment around in the subway for hours every day. Also, I thought that if anything was going to happen to me down there I wanted to be in good shape, or at least to believe that I was. Each morning I carefully packed my cameras, lenses, strobe light, filters, and accessories in a small, canvas camera bag. In my green safari jacket with its large pockets, I placed my police and subway passes, a few rolls of film, a subway map, a notebook, and a small, white, gold-trimmed wedding album containing pictures of people I’d already photographed in the subway. In my pants pocket I carried quarters for the people in the subway asking for money, change for the phone, and several tokens. I also carried a key case with additional identification and a few dollars tucked inside, a whistle, and a small Swiss Army knife that gave me a little added confidence. I had a clean handkerchief and a few Band-Aids in case I found myself bleeding.

As I went down the subway stairs, through the turnstile, and onto the darkened station platform, a sinking sense of fear gripped me. I grew alert, and looked around to see who might be standing by, waiting to attack. The subway was dangerous at any time of the day or night, and everyone who rode it knew this and was on guard at all times; a day didn’t go by without the newspapers reporting yet another hideous subway crime. Passengers on the platform looked at me, with my expensive camera around my neck, in a way that made me feel like a tourist—or a deranged person.

It was hard for me to approach even a little old lady. There’s a barrier between people riding the subway—eyes are averted, a wall is set up. To break through this painful tension I had to act quickly, on impulse, for if I hesitated, my subject might get off at the next station and be lost forever. I dealt with this in several ways. Often I would just approach the person: “Excuse me. I’m doing a book on the subway and would like to take a photograph of you. I’ll send you a print.” If they hesitated, I would pull out my portfolio and show them my subway work; if they said no, it was no forever. Sometimes, I’d take the picture, then apologize, explaining that the mood was so stunning I couldn’t break it, and hoped they didn’t mind. There were times I would take the picture without saying anything at all. But even with this last approach, my flash made my presence known. When it went off, everyone in the car knew that an event was taking place—the spotlight was on someone. It also announced to any potential thieves that there was a camera around. Well aware of that, I often changed cars or trains after taking pictures.

Advertisement

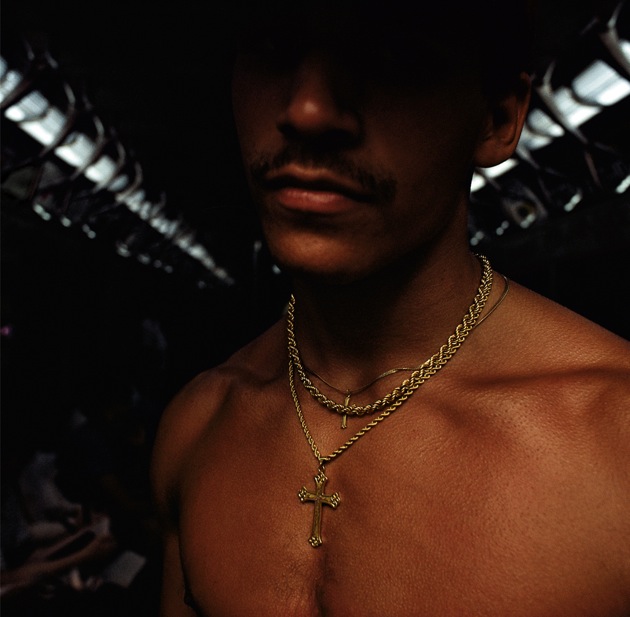

At first I photographed in black and white. After a while, however, I began to see a dimension of meaning that demanded a color consciousness. Color photography was not new for me—most of my commissioned work and all of my films have been done in color. But color in the subway was different. I found that the strobe light reflecting off the steel surfaces of the defaced subway cars created a new understanding of color. I had seen photographs of deep-sea fish thousands of fathoms below the ocean surface, glowing in total darkness once light had been applied. People in the subway, their flesh juxtaposed against the graffiti, the penetrating effect of the strobe light itself, and even the hollow darkness of the tunnels, inspired an aesthetic that goes unnoticed by passengers who are trapped underground, hiding behind masks, and closed off from each other.

I began to explore the different subway lines, taking them to the end, then back again. Most of the time I didn’t set a destination, but chose to be carried wherever the subway would take me, occasionally referring to the map and making mental notes of places I wanted to return to.

One day I entered an express train deep inside Brooklyn on the Seventh Avenue express line that runs from 241st Street in the Bronx across Manhattan to New Lots Avenue in Brooklyn, a distance of more than twenty-five miles. It was after the morning rush hour, when trains far from Manhattan are almost empty. I had little idea where I was, except that I had been crossing a neighborhood called Crown Heights. I was looking at the map when the doors opened and in came a fierce youth with a deeply gouged scar running across his face.

He sat down across the aisle from me, gave me a hard look, and said in a low, penetrating voice, “Take my picture, and I’m going to break your camera.” I quickly said, “I don’t take pictures without people’s permission, and I always send them prints.” I reached into my jacket pocket for my portfolio, walked over to him, and slowly leafed through the sample photographs while sitting on the edge of my seat. After looking, he paused for a moment, then turned to me and said, “Okay, take my picture.” I went back to my seat and began to photograph, taking a few frames. Then I wrote down his address. He left, disappearing along the platform as the train gained speed. A couple of weeks later I sent him some prints of our encounter together, but the post office returned them with a red stamp on the envelope that said: RETURNED TO SENDER—MOVED—LEFT NO ADDRESS.

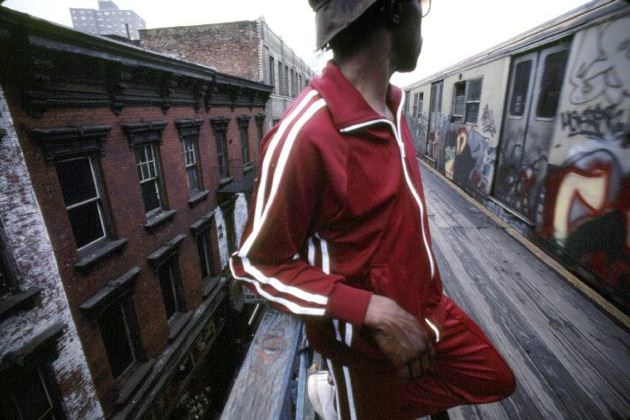

As I ventured out into various sections of the city on the different lines, I found that many of the trains emerged from underground. From the elevated tracks I could clearly see many of the neighborhoods that make up New York. Some areas of the city seen through subway windows look devastated and bombed out, with housing projects looming like impassive canyon walls. Still others were made up of neat family houses with fenced-in backyards. There were views of old ethnic neighborhoods, often with large ornate churches, reminiscent of picturesque hillside towns in other countries. The harbor docks, Statue of Liberty, and Manhattan skyline were all framed through the windows of the train.

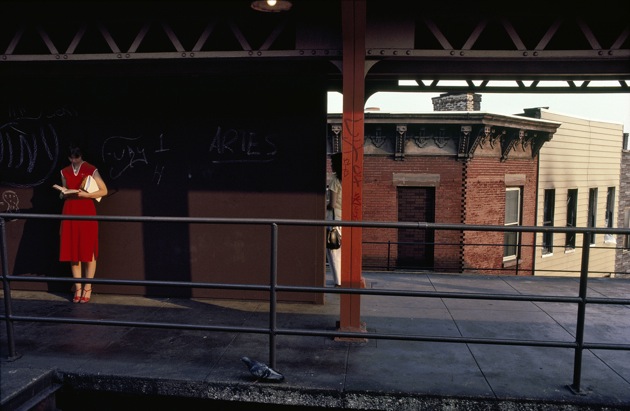

One spring day, just before sunset on the M line’s elevated platform at Myrtle Avenue, a warm breeze began to ruffle the light dress of a young woman standing alone on the platform. I wanted to photograph her, but I didn’t want to startle or frighten her. As I approached, I excused myself and explained my purpose. She gave me permission to photograph her. I told her I wanted to capture the atmosphere I felt standing on the platform, and asked if she could slip back into her mood undisturbed. The wind picked up as the light fell at sunset, and I took a few more photographs. I asked her if she felt vulnerable standing in the near dark on a desolate platform in a neighborhood some called dangerous. She told me she’d been born in the area, lived with her parents there, and would probably never move away. She went on to tell me about her animal-like sense of danger, which had made her aware of me stalking her on the platform, and placed her on alert.

Advertisement

I began to go out late at night and in the early-morning hours. There are stations that are deeper underground and warmer in winter, where I have seen people asleep on benches, wrapped in blankets, in the hours past midnight. The subway becomes an empty no man’s land for the homeless, a few late-night riders, and the roaming animals of prey who inhabit the subway until the first morning workers begin to fill the platforms and trains around 5:00 a.m.

It was about three in the morning one night when I saw, at the end of a long, dark platform, what looked to me in the dim light to be a pile of rags near some utility stairs. I thought there might be people sleeping there and cautiously approached. As I neared the heap, I saw that it was a man sleeping naked. Behind him on the stairs others were sleeping in heavy, dark coats. I came up closer to the man. Despite knowing that my flash might awaken those behind me, I took a few pictures. He moved a little. I backed off and looked around, then approached again. A train came, and I rode for a while, thinking of the man lying there, and remembering a scene I’d witnessed in Calcutta of a youth lying naked and dead on a street in the sunshine. I returned to the naked sleeping man a few more times that night, and then went home. The next night nobody was there. The wine bottles and debris had been swept away, and everyone had vanished.

It was July, and the sun had begun to warm the stagnant air in the subway. I rode the JJ line out of the tunnel of Essex and Delancey Streets on the Lower East Side across the Williamsburg Bridge over the East River to Brooklyn. Here the elevated train crosses the dense communities of Bushwick and Bedford-Stuyvesant. Through the windows of the passing train I could see an endless grid of tenement buildings and deserted Sunday morning streets. I decided to move away from this despair and changed at Broadway-East New York for the A train that would take me to Jamaica Bay and the fresh breezes of the Atlantic Ocean. I sat in the next-to-the-last car of the train, which was almost empty.

I noticed two seventeen-year-old boys in the very last car smoking pot. I entered the car to see them more clearly, but decided not to make contact with them. They looked withdrawn and dejected, slumped in their seats. I stood for a few moments watching the view of the Manhattan skyline diminishing in the hazy distance, then sat down a few seats away from them with my back turned. One of the boys got up, walked past me, and started talking to a young girl sitting across the aisle. The train slowed down and stopped at the Chauncey Street station, the doors opened and the youth quickly turned from the girl and rushed at me with the blade of a knife protruding from between his thumb and forefinger. He stood astride me, the blade next to my jugular. I heard his deep, guttural voice: “Gimme that camera.” His face was thin and dark, his eyes wide and desperate. I thought about the razor blade at my throat, and my words were, “Take the camera.” His partner behind me released the door, and they were out of the car with the camera, running down the platform stairs. As the train pulled away from the station, I stood at the door in shock. Then it occurred to me that I might be cut and bleeding. I felt my body, but there was no blood. I realized that they hadn’t gotten my camera bag, and that I had another camera and a couple of lenses left. I ran to the middle of the train to find the conductor who put out the alarm.

At the next station I was met by the police, who escorted me to the station house where I answered questions and filled out papers. Later, two detectives in an unmarked police car drove me through the neighborhood. As we cruised through the sweltering streets, people sitting on tenement stoops looked at us in a suspicious way that told me this had happened here before. Sitting in the backseat of the police car, I was no longer the heroic hunter stalking dangerous prey, but just another pathetic mugging victim. The detectives took me back to the subway stop, and I decided to continue my journey to Far Rockaway and Broad Channel, to the ocean. Here the train crosses the bay on tracks just a few feet above the water, like a racing sailboat. Moving across the inlet, it flushes marsh birds and passes pleasure yachts heading for the open sea. The sun was now low in the sky. Young people returning from the beaches along Far Rockaway began to fill the train. They all looked like muggers to me, but slowly I began to make contact with them as I took pictures during the long journey home.

In transforming the grim, abusive, violent, and yet often serene reality of the subway into a language of color, I see the subway as a metaphor for the world in which we live today. From all over the earth, people come into the subway. It’s a great social equalizer. As our being is exposed, we confront our mortality, contemplate our destiny, and experience both the beauty and the beast. From the moving train above ground, we see glimpses of the city, and as the trains move into the tunnels, sterile fluorescent light reaches into the stony gloom, and we, trapped inside, all hang on together.

This essay is drawn from the introduction to Bruce Davidson’s Subway, a collection of his photographs of New York City’s subway system. The book has just been re-published in a 25th anniversary edition by Aperture.