Few people I know in Cairo got much sleep last Sunday night. The voting stations were set to open at 8AM the following morning, and everyone was concerned that the day would be marred by the increasingly lethal violence we have witnessed in recent weeks. “I’m going to go as early as possible, before it gets crowded or anything bad happens,” my mother had told me. It seemed everyone had thought the same—by the time I reached my neighborhood voting station at 7:15AM Monday, it was already packed—there were at least 2,000 people there. A friend called me from her own voting station about 40 minutes away as I arrived, saying she couldn’t even see the end of the line.

For much of the past ten months, you could gauge the direction Egypt was moving in by seeing what was happening in Tahrir Square. Ever since serving as the epicenter of the revolution, it has been the place where the different post-Mubarak factions—the Islamists, unemployed youth, trade unions, liberal and secular parties, even government workers and the police—have staged rallies or aired their grievances. If Tahrir was calm, things were generally considered to be improving; if it was occupied, or worse—the site of confrontation with thugs or the military—it meant the country was in trouble.

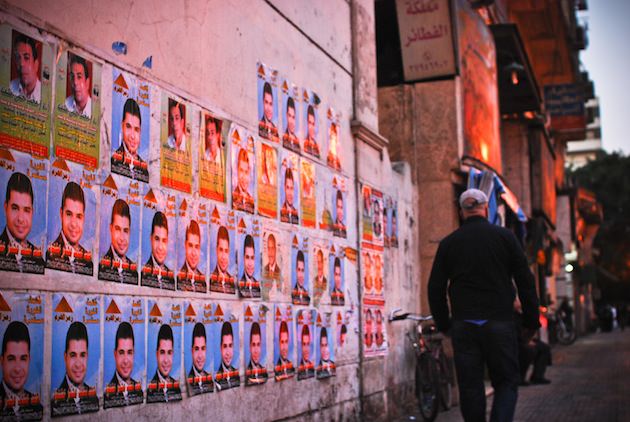

This week, however, as we started voting in the country’s first parliamentary elections since the fall of Mubarak, that center of gravity seemed to have shifted. The square was once again occupied by activists protesting the recent violence at the hands of riot and military police, and they had announced they were boycotting the vote, on the grounds that it would legitimize the rule of the Military Council that they sought to remove. But by Monday morning, the “boycotters” were a muffled minority numbering only a few hundred people. Everywhere else, throughout Cairo and across the country, voters came out by the tens of thousands, often enduring hours-long lines to cast their ballots. At the only voting station designated for women in my neighborhood—in the Egyptian system, women and men generally vote in different places—the line went down a side street, round two corners, and ended at one end of a main street a kilometer away.

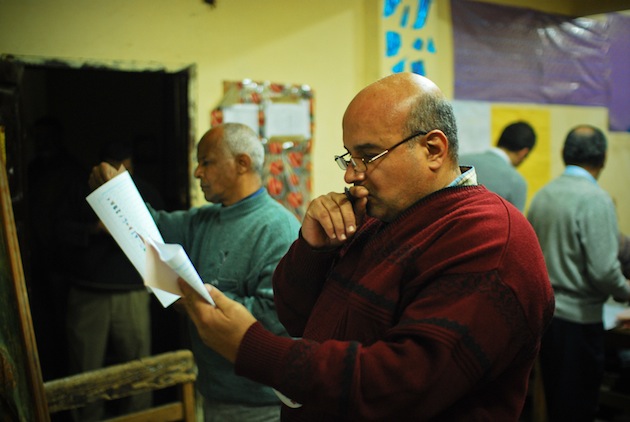

With voter turnout averaging as little as 8 to 10 percent in previous parliamentary elections, few voting stations had been allocated—as many as 24,000 people had been assigned to some, under the assumption that only a fraction of registered voters would show up. In the past few months, the term “Hezb el Kanaba,” the “party of the couch,” has been frequently tossed around; Egyptians have been cast by the media as unlikely to move beyond their sofas to the ballots. Monday’s voters proved this wrong. “I’ve been in line for four hours and I won’t give up,” one middle-aged woman told me as we waited. Three hours later, she had finally cast her vote—her first ever in the country’s parliamentary elections. There were 18,000 of us in that same line who voted—assigned to that voting station based on our National ID numbers and registered home addresses. My own wait was six hours, a cousin waited seven.

The road to these parliamentary elections has been bumpy. When we went out for our first ‘free and fair’ vote back in March—a [Yes/No vote on a package of nine constitutional amendments] (http://www.nybooks.com/blogs/nyrblog/2011/mar/24/egypts-first-vote/)—most of us expected we would already have a parliament in place by now. Instead, we have endured protests and gun-battles and church burnings and riots. Over 100 people have been killed in such violence since the fall of the old regime—including more than 40 in the chaotic week preceding the election itself. Indeed, the election took place at one of the lowest moments since the revolution. On November 18, protesters staged a large-scale protest in Tahrir Square against a government draft document that seemed to give the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) a controlling part in the writing of a new constitution. The demonstration went off peacefully, but late that night, riot police stormed the square to forcefully clear it of the remaining protesters. In the days following, clashes between the police and protesters escalated, with the state’s various security forces unleashing a kind of violence that has rarely been seen since the revolution; teargas was fired in toxic amounts, poisoning many and killing some, and specially-trained forces seemed to be targeting protesters’ eyes. In the course of a single day, five young men lost sight in one eye, and one man—Ahmed Harara—was blinded (he had lost his first eye on January 28). “You would think we’re at war,” someone had tweeted.

Advertisement

Amid the chaos, many liberal parties suspended their campaigns and some called for the elections to be postponed. But after the violence had flared on for several days, a truce was brokered by the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar (Egypt’s highest Islamic authority), and the SCAF insisted the elections must be held as planned. The vote began on schedule, and to nearly everyone’s surprise, was astonishingly calm. Indeed, in this first of a three-stage parliamentary election process that will continue on December 14-15 and January 3-4, some 52 percent, or more than 9.1 million of the 17.5 million registered voters designated to vote in phase one turned out to vote, often spending much of the day waiting patiently in line to do so.

In my line, people shared juices and coffees and biscuits and croissants. Grocery stores gave out free snacks, neighborhood residents offered chairs. People compared notes on who to vote for, and why. Except for a few women wearing the face-veil, everyone else was voting liberal. The movie star Yossra, standing behind me, answered “El-Kotla”—referring to a liberal coalition of parties—when someone asked her who she supports. In my district, young and old alike showed up—the elderly supported by children and grandchildren (some just there to watch), some with walkers, others on wheelchairs, one woman with her respirator. Of everyone I spoke to that day, only a single woman had voted before. “The polling stations were always completely empty,” she told me, “Not more than five or six people there.” Under the former regime, there seemed to be little point—we all knew that Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party would end up with a sweeping win, regardless of what the ballots said. This time, the chance of a fair vote seemed likely.

We were to vote for two candidates: one in the “professional” category, and one in the “farmer” category (candidates could register in the latter category if they had a certain amount of agricultural land to their names, the idea being to have a parliament that represented all spectrums of society); plus either a party or party coalition list. Each candidate or list was identifiable by a symbol (dreamt up and assigned, randomly it seemed, by the Higher Election Commission). Most people in my line were going for the eye, the flower bouquet, and the motorcycle. I voted for the blender, the pyramids, and the train.

The fact that the elections went off smoothly, and that such great numbers of people took part, is powerful evidence that a large majority of Egyptians have not given up on the revolution. It was an indication that the military, however much it is in disfavor, was also still capable of maintaining an orderly election process (army and police were deployed at every voting station), and keeping with its commitment to holding the elections on time. Above all, though, it suggests just how high the stakes are. When the election process finally ends on January 10, after voters in all 27 governorates have cast their ballots, they will have determined who occupies 498 of the 508 seats in parliament. Although under current rules, the new parliament will have limited powers (the Military Council continues to have overriding authority), it is expected that the parliament will pressure the military and pass legislation giving itself the absolute right to appoint a new government and draft the long-promised new constitution. Many thus believe the political balance of the new parliament will determine the ideological direction the country might take.

So when Egyptians went out to vote on Monday and Tuesday, many felt they were casting their ballots on what they hoped their future will look like. Many of the country’s 82 million live on minimum or day-to-day wages (40 percent of the population live on $2 a day or less). For them, stability, security, and basic guarantees for survival are paramount. People I spoke to at polling stations in poorer districts of Cairo, like Imbaba, Shubra, and Ain Shams, said they wanted “stability and a strong economy,” and that “ultimately it is in God’s hands.” For other groups, including the Islamists, a state governed by the principles of Islam is the answer to the country’s social and economic woes. Still others, including a minority of more secular-minded Egyptians and much of the country’s 10-million-strong Christian community, seek a modern state with the liberties afforded in any western democracy. (In my line in the affluent Zamalek neighborhood, the main topic of discussion was what the Islamists would do if they took over—“Will they ban alcohol and bikinis?”—and if they did, where people would immigrate to: America, Canada, and in the case of some 20-year-old college students, Brazil).

The broad contrasts between liberals and Islamists played out first in campaign messaging (liberals spoke of a secular state, Islamists, trying to speak for the masses, focused on the cost of food), and then in the vote itself. As the initial results slowly trickle in, they are revealing that the Islamists, with all their differences and shades of moderation and fanaticism, look set to take a sweeping majority win. As I watched votes being counted under high-security and heavy monitoring at one Cairo ballot-counting station on Tuesday night, Mohamed Fawzy, a liberal MP hopeful, told me that he was prepared for the worst: “we shouldn’t forget that the Muslim Brotherhood had been plotting and preparing for this moment for 80-years.” Even in my district, considered one of the most liberal in the city, the Islamists are reported to be ahead. (The final tally is expected next Wednesday, after Monday’s run-offs.)

Advertisement

On Thursday morning, as the news began to spread that the political arm of the Muslim Brotherhood—The Freedom and Justice Party (FJP)—was in the lead with about 45 percent of the votes, and that the ultra orthodox Salafis were now in second place with 22 percent, I received call after call from family and friends. Few people said hello. “I’m scared,” one friend began. “I can’t believe it,” another said. “What does this mean,” another started. And more and more described the results as a “slap across the face” or “reality check.” Although many expected that the Islamists would win a majority, it had been assumed at least in this first round—which includes more liberal districts—their lead, if any, would be marginal.

The reality is that most Egyptians want guarantees that basic needs will be met. They want to put their children through school, they want decent jobs, they want food each day, and they want affordable and reliable health care. The Muslim Brotherhood are, in many ways, the only organized, and as well the largest, faction who in the past have offered people what they seek; for years they have been offering social services to their communities where the government has failed, and in recent months, they are the only ones who have spoken the language of the street. At an election rally hosted by the FJP a few weeks ahead of the vote in the impoverished neighborhood of Imbaba, I spoke to dozens of men and women who had stories to share of how the Muslim Brotherhood had helped alleviate some of their basic struggles (selling meat at wholesale prices, offering subsidized school supplies, offering free after-school lessons, helping with medical treatment). One woman, the 48-year-old mother of five, told me: “One of the biggest costs for a mother is after-school lessons. The public schools here are very bad, and the only hope for our children is in private lessons, which are extremely expensive. No one can afford them without being a millionaire. God bless the Brotherhood for helping us with these, and for providing our children with better futures.”

At the polling stations themselves, the Brotherhood representatives were the most efficient; they were easily identifiable by their FJP caps and pins (in Zamalek too), and were on hand to answer any questions people might have had about their party or candidates. Even inside the voting stations, their members stood in corners tallying the numbers of people coming in to vote (“It’s to calculate voter turnout,” one of them told me.) Although many liberals were quick to accuse the Islamists of violating campaign regulations (parties and candidates are meant to stop campaigning 24 hours before the ballots open), liberal parties were campaigning too; as I stood in line waiting to vote, I received three text messages from El-Kotla, the coalition headed by the liberal “Free Egyptians” (the party founded by the billionaire telecom tycoon Naguib Sawiris). “Vote for El-Kotla, Vote for El-Kotla, Vote for El-Kotla,” the messages read in Arabic.

There are still many weeks to go until we have a final result and a concrete picture of what our parliament will look like, and in those weeks as much could happen as has unfolded in past ones. But one thing is clear: the majority of Egyptians want stability, they want promises of assurance, and they also want a party that believes in what they do—the “hand of God.” It has also become clear that while the liberals are much more concerned about countering the Islamist threat, the Islamists themselves are busy trying to push out the army and rise to power themselves. In fact, some liberals, who were initially fighting against the participation of former regime party members in these elections, and who were against the army having an upper hand over the parliament, have now changed their minds: Naguib Sawiris’ “Free Egyptians Party”, for example, includes several hard-core former Mubarak supporters who were a part of the dissolved NDP—among them, is a gentleman who was one of the biggest advocates for Gamal Mubarak’s succession from his father.

With a largely Islamist parliament, many are concerned that tourism might be affected as laws are passed to ban bathing suits and alcohol and cover pharaonic monuments (in recent months several Islamists have proposed this). People also worry that the role of women in society might change. Although the Muslim Brotherhood in particular has so far expressed its commitment to building a democratic and moderate society (their party’s campaign video shows unveiled women as well as Copts), many fear that once the Islamists settle in power, their tune might change.

In the days since the vote, the country seems, once again, to be divided: between those who support the Islamists and are already celebrating victory, and liberals who are anxious about what that victory might mean for their own day-to-day lives. In the wealthy Cairo suburb of Heliopolis, the one district where the secular and liberal candidates and parties defeated the Islamists by a huge margin (and where, as it happens, former president Hosni Mubarak kept his residence), a group of residents have started a Facebook page: “Welcome to The Republic of Heliopolis,” complete with a map that defines the borders of the new republic, and the names of the individuals who would govern it. The page administrators write:

“We’re the only district where a liberal beat a Muslim Brotherhood by a landslide. We’re the only district that voted for a candidate with long hair whose girlfriend is a movie star. People in Montazah, Alexandria, voted for a guy who called democracy “haram” or forbidden. So we presume that it is quiet understandable why we want to be separated from Egypt. Why we want nothing to do with the rest of our previous country.”

In my neighborhood, everyone is discussing what will happen. Some friends have already decided that it is time to leave. Others are more determined than ever to fight for the cosmopolitan Egypt we have long known. Groups of friends and acquaintances are busy preparing flyers and Facebook pages and email circulars to counter the campaigning of the Islamist groups. With over a month left, and two-thirds of the parliamentary seats yet to compete for, many say that the fears, and even celebrations, are premature. Worst-case scenario, an old school friend tweeted, “I’ll move to Heliopolis, I like how they think over there.”