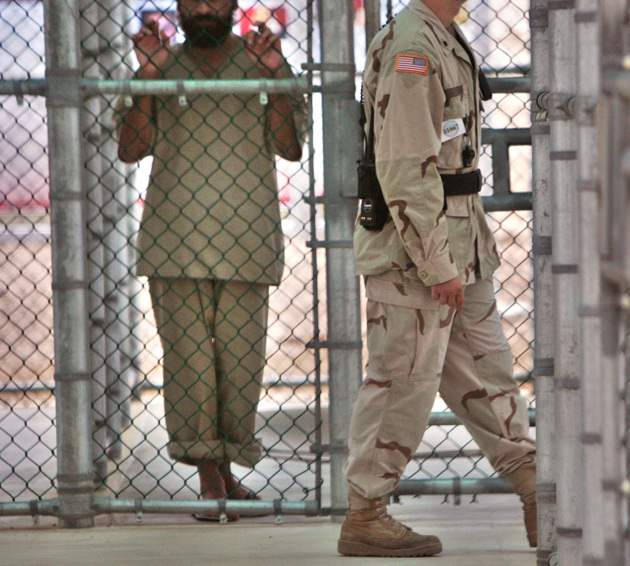

For a moment, it seemed that President Obama would actually stand up to Congress on Guantanamo and military detention, something he has not yet had the guts to do. As I wrote in the NYRblog last week, the president had threatened to veto the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) after both houses of Congress approved provisions in the new bill that made it impossible to close Guantanamo, effectively required the continued incarceration of detainees already cleared for release, expanded the government’s authority to detain suspected terrorists indefinitely, and prohibited civilian criminal trials for some terror suspects.

But on Wednesday, after the Senate and House worked out their differences and adopted some revisions to the detention provisions, the White House announced that the veto was off the table. The president didn’t even have the courage to take responsibility himself. As the White House press statement put it, “the President’s senior advisors will not recommend a veto.” Why did the president back down? Only he and his senior advisors know the answer to this—though at this point in the administration one can hardly say it is out of character. In his defense, it is never easy to veto a defense authorization bill, and it’s not clear he would have won an override fight. The Senate voted for the initial bill 93-7, and the House voted 406-17 to approve the revised bill. Moreover, under pressure of the veto threat, the conference committee did eliminate some of the worst aspects of the NDAA provisions, such as a prohibition on civilian trials for suspected terrorists, and made other provisions less onerous, for example, by giving the president more leeway to use criminal rather than military procedures for suspected terrorists, and tying many of its provisions to existing law.

Yet one senior advisor, FBI Director Robert Mueller, testified in Congress this week that the amended bill would still make his agents’ jobs more difficult, by making it unclear whether the FBI or the military had authority to arrest terror suspects in the United States. If the military become involved in a case as the new legislation indicates it must, Mueller testified, it could stymie the FBI’s vital task of gaining information from a suspect. According to Mueller, “the possibility looms that we will lose opportunities to obtain cooperation from the persons in the past that we’ve been fairly successful in gaining.”

Indeed, the law as amended continues to contain extraordinarily dangerous principles. It creates a presumption in favor of indefinite military detention for foreign al-Qaeda suspects, even if a criminal arrest and prosecution would be the preferred course. And it imposes this presumption even for foreigners caught within the United States. While the law permits the president to waive that, the presumption is still wrong: given its inconsistency with basic principles of due process, indefinite military custody should be the last, not the first resort.

Equally problematic, the law puts Congress’s stamp on a dubious—and untested—interpretation of military detention authority. The law provides that indefinite detention without charge may be imposed on anyone who has provided “substantial support” to groups that are “associated forces” of al-Qaeda; but it leaves undefined what constitutes “substantial support” and which groups might qualify as “associated forces.” Thus far, the lower federal courts have upheld detention of al-Qaeda or Taliban members, but not mere supporters, much less supporters of associated forces. And there is much dispute about whether the laws of war permit detention in those circumstances. Now Congress has essentially predetermined that question. Unless this and future administrations construe these provisions as limited by the laws of war, they risk authorizing detention that the laws of war would not.

Most disturbingly, the law still effectively prevents President Obama from closing Guantanamo. He can’t use any funds to build or modify a facility in the United States to house Guantanamo detainees—a necessary precondition to closing the prison. He cannot transfer any Guantanamo detainee to the United States, even to face criminal trial. And he cannot release any detainee to another country without meeting onerous certification requirements regarding that country’s security measures that, until now, have proven impossible to meet. (To its credit, the administration did get the conference committee to water down the certification requirements somewhat, but it still seems unlikely that they will be met.)

As I noted in my earlier blog post, the military has determined, after careful review of all the remaining detainees at Guantanamo, that more than half of them don’t need to be there. They have been cleared for release. But as a practical matter, Congress’s law cuts off all options for getting them out. Under the laws of war, military custody is lawful only where necessary to keep an enemy fighter from returning to the battle. To hold a person our own military has determined does not pose that threat is plainly illegal, and violates the most fundamental right of liberty. Yet Congress’s law mandates it. And President Obama has now agreed to sign it.

Advertisement

After hearing of the President’s about-face, the Senate passed the NDAA as revised on Thursday, December 15, 2011. It was the 220th anniversary of the Bill of Rights, although apparently those rights only apply to some.