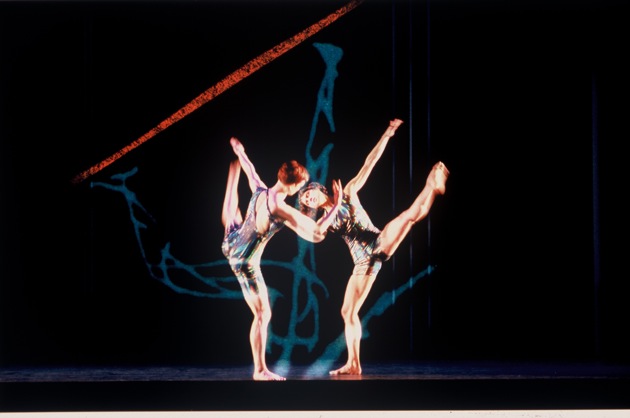

Halfway through the first section of Rainforest, the work that Merce Cunningham choreographed for his splendid company in 1968, the character initially played by Merce sits peaceably downstage left, while the character originally danced by Barbara Dilley leans against him in a position of luxurious repose, her head on his shoulder. A minute earlier, they have prowled around each other in tight circles like dogs, or lions. Great moments of stillness pass, and then the character danced back then by the much younger performer Albert Reid strides over and sits in close proximity to Merce and Barbara. In a flash, she is kneeling next to him, having transferred her head from Merce’s shoulder to his. Merce squats in alarm next to this new couple for a moment, but the situation is becoming highly fluid. Within minutes the character danced by the kingly and long-legged Gus Solomons will stride, stiff and purposeful, towards where Barbara is lying and slowly, carefully, get down on all fours and, with the crown of his head, push Barbara right below her shoulder blade, and then underneath her hip bone, until she rolls languorously away from him. He’ll push her again, she’ll roll again, and the initial moment of union between Merce and Barbara will have passed, as moments do in cities and jungles, possibilities arriving and breaking up and reforming again as something else, to our regret or perhaps, sometimes, our joy.

It is sequences of pure emotional drive like this one, and the ongoing flow of moments of sheer beauty, that kept packed audiences cheering and clapping through endless curtain calls when the piece was performed by current members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in Paris last week—but it is also nostalgia for what is about to be lost forever. In an extraordinary act of artistic self-immolation, the creator of some of the twentieth century’s most moving dance works decided in his final years that his company should not outlive him. With the company’s board of trustees giving form to his expressed wish, it was decided that following his death, which occurred on July 26, 2009, at the age of 90, the company would embark on one final world tour, and then everything would go. Company, studio, musicians, dancers, and perhaps most tragically, the school—the entire institution created with such great effort by Merce over a fifty-year period—are slated to close down at the Park Avenue Armory on New Year’s Eve

Last week in Paris, during the final days of the world tour, Trevor Carlson, the company’s executive director, told a small audience that when the board’s final plans for the company’s dismemberment were presented to Merce a few months before his death, he approved it all; the generous arrangements of a one-year transition period for the dancers, the closure of the school in the West Village. And then he asked for one more thing, Carlson said: “I’d like the final performances to be in New York, and I’d like the tickets to cost ten dollars.”

There is not a single ticket remaining at the Armory for the final three evenings of events—selections from the repertory presented in a non-proscenium setting. But if you never saw the Cunningham company you might show up before starting time on December 29th, 30th, or 31st and see what price the scalpers will let you have a ticket for. Even if the Armory gets more crowded than a department store the day after Christmas, you might still catch a glimpse of the sheer elegance of Merce’s choreography, its timelessness, the breathtaking skill and beauty of his current, and last, crop of dancers, and the reckless commitment with which they throw themselves into every movement.

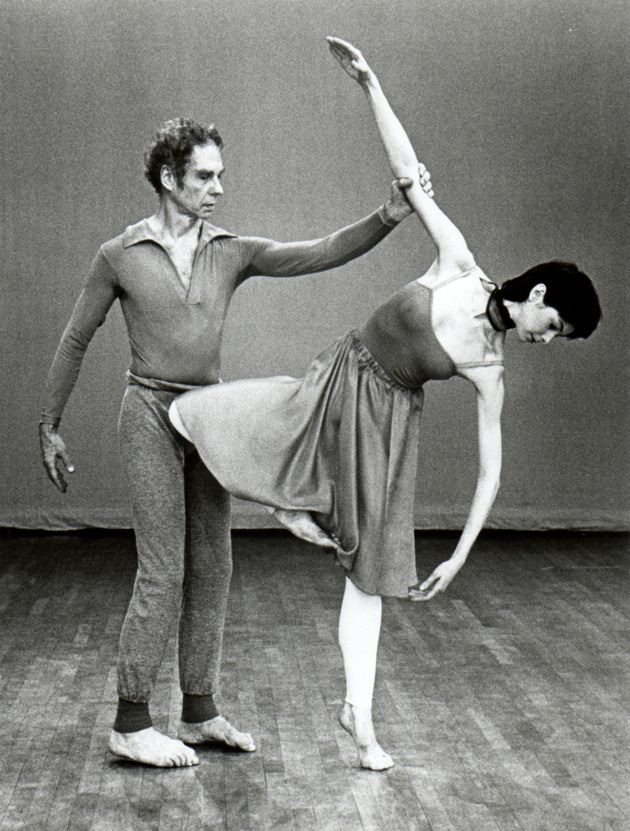

Merce developed the guiding elements of his art with his lifelong partner, John Cage, and, among others, with his frequent collaborators on stage design, Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. The group believed that dance, music, and visual arts could co-exist together on a stage, but should not be forced to depend on each other (as, to put it broadly, the music, steps, and costumes do in Swan Lake). Using the I Ching and, later, a computer, to enforce the randomness of movements and sequences, Merce nearly killed his dancers and himself in an assault on the impossible: to interrupt the body’s logical way of shifting from one movement to the next, from one single direction in space to an unpredictable multiplicity of fronts. Like other mid-century choreographers, he unmoored dancing from narrative, but until he started working with computers, he did not eliminate character from his dances: bodies were the characters. In Rainforest, Gus Solomon’s body told one story, Merce’s another. Merce insisted throughout that his dances were not abstract: “I have never seen an abstract human body” he often remarked. He himself danced like a man on fire.

Advertisement

His mode of operation was, however, cool. And he was always modern. Those of us who were privileged to study with him at whatever point in his long career will cherish forever the physical challenges he posed for a dancer, the intellectual alertness required. But we loved Merce’s unfailing courtesy, too. (Once, in the weeks after Szechuan food took New York by storm, I walked into the formica-table restaurant on Chatham Square that was the first outpost of this new cuisine and found Merce at a table with Cage, and, if I recall correctly, Buckminster Fuller. I was a bashful teenager, but he stood up to greet me as if I were a great lady.)

Followers like myself also loved his senseless determination to make every piece new, even if it meant losing audience members unwilling to work that hard for the payoff: in a favorite story, his brother once asked, “Merce, when are you going to make something people like?” We loved Merce’s courage: he showed up for work when he was exhausted, when he was injured, when he was suffering, and as several former dancers who flew over to the Paris season last week to say good-bye recalled, he never, ever, just went through the motions even in rehearsal; he always danced full-out. In his later years, wheelchair-bound with rheumatoid arthritis, he turned to computerized movement programs to choreograph, and was working out a new dance in his mind the day he died.

Perhaps I loved most of all the times that I showed up at the studio a little early for class and found him already there in his practice clothes, carefully sweeping the floor.

Whether he should have been allowed by his board to torch everything he worked so killingly hard to create will be debated for a long time, along with the question of why he did it. “I never saw Merce express an emotion,” one of his dancers said last summer at a commemorative event at Lincoln Center, but watching him on stage it always seemed to me that he was a man capable of great fury, an emotion he used to marvelous theatrical effect but perhaps less fruitfully offstage. There were reasons to consider closing down the Merce Cunningham Dance Company following his death, to be sure: it faced a devastating economic crisis following the 2008 recession, and without the constant production of new works once Merce was gone it would have been increasingly difficult to fill a theater or get bookings. But mostly, the man who always loved challenges and difficulties was too old and frail to take charge of this new crisis himself. In many dances revived for the farewell tour, like Suite for Five and Rainforest, the curtain drops when Merce—or the dancer playing his character—walks off the stage, sometimes, as in Quartet, after a solo of despair or rage. That must have been the ending he needed this time, too.