“For a lazy man I’m extremely industrious.”

—William Dean Howells

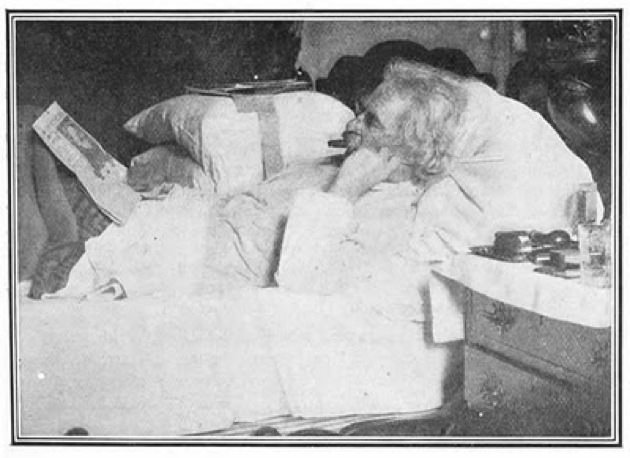

All writers have some secret about the way they work. Mine is that I write in bed. Big deal!, you are probably thinking. Mark Twain, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Truman Capote, and plenty of other writers did too. Vladimir Nabokov even kept index cards under his pillow in case he couldn’t sleep some night and felt like working. However, I haven’t heard of other poets composing in bed—although what could be more natural than scribbling a love poem with a ballpoint pen on the back of one’s beloved? True, there was Edith Sitwell, who supposedly used to lie in a coffin in preparation for the far greater horror of facing the blank page. Robert Lowell wrote lying down on the floor, or so I read somewhere. I’ve done that, too, occasionally, but I prefer a mattress and strangely have never been tempted by a couch, a chaise longue, a rocker, or any other variety of comfortable chairs.

For some reason, I’ve never told this to anyone. My wife knows, of course, and so did all the cats and dogs we ever had. Some of them would join me in bed to nap alongside me, or to watch in alarm as I tossed and turned from side to side, occasionally bumping into them without intending to, in a hurry to jot something down on a small writing pad or in a notebook I was holding. I’m not the type who sits in bed with a couple of pillows at his back and one of those trays with legs that servants use to serve rich old ladies their breakfast in bed. I lie in a chaos of tangled sheets and covers, pages of notes and abandoned drafts, books I need to consult and parts of my anatomy in various stages of undress, giving the appearance, I’m certain, of someone incredibly uncomfortable and foolish beyond belief, who, if he had any sense, would make himself get up and cross the room to the small writing table with nothing on it, except for a closed silver laptop, thin and elegant.

“Poetry is made in bed like love,” André Breton wrote in one of his surrealist poems. I was a very young man when I read that, and I was enchanted. It confirmed my own experience. When the desire comes over me to write, I have no choice but to remain in a horizontal position, or if I have risen hours before, to hurry back to bed. Silence or noise makes no difference to me. In hotels, I use the “Don’t Disturb” sign on the door to keep away the maids waiting to clean my room. To my embarrassment, I have often chosen to forgo sightseeing and museum visits, so I could stay in bed writing. It’s the illicit quality of it that appeals to me. No writing is as satisfying as the kind that makes one feel that one is doing something the world disapproves of. For reasons that are mysterious to me, I’m more imaginatively adventurous when I’m recumbent. Sitting at a desk I can’t help feeling I’m playing a role. In this little poem by James Tate, you could say, I’m both the monkey and the mad doctor performing the experiment on him.

TEACHING THE APE TO WRITE POEMS

They didn’t have much trouble

teaching the ape to write poems:

first they strapped him into the chair,

then tied the pencil around his hand

(the paper had already been nailed down).

Then Dr. Bluespire leaned over his shoulder

and whispered into his ear:

“You look like a god sitting there.

Why don’t you try writing something?”

This habit of working in bed had its beginning in my childhood. Like any other normal and healthy child, I often pretended to be sick on mornings when I hadn’t done my homework and my mother was already frantic about being late for work. I knew how to manipulate the thermometer she would insert in the pit of my arm and produce a high enough temperature to alarm her and make it mandatory that I skip school. “Stay in bed,” she would yell on her way out of the door. I obeyed her conscientiously, spending some of the happiest hours in my memory reading, daydreaming and napping till she returned home in the afternoon. Poor mother. It may have been only a coincidence, but I was shocked to learn after her death that she had almost married a Serbian composer in Paris in the 1930s who used to compose in a bathtub. The thought that he could have been my father both terrifies me and delights me. I’d be in bed dashing off verses and he would be in the tub working on a symphony, while my mother would be screaming for one of us to come down and take out the garbage.

Advertisement

In past centuries, in unheated rooms, it made perfect sense to stay under the covers as long as one could, but today, with so many comforts and distractions awaiting us elsewhere in the house, it’s not so easy, even for someone like me, to stay in the sack for hours. In the summer, I can lie in the shade under a tree, listen to the birds sing, to the leaves make their own soft, dreamy music—but that’s just the trouble. The more beautiful the setting, the more abhorrent any kind of work is to me. Put me on a terrace overlooking the Mediterranean at sundown and it will never occur to me to write a poem.

In New Hampshire, where I live, with five months of snow and foul weather, one has a choice of dying of boredom, watching television, or becoming a writer. If not in bed, my next writing-place of choice is the kitchen, with its smells of cooking. Some hearty soup or a stew simmering on the stove is all I need to get inspired. At such moments, I‘m reminded how much writing poetry resembles the art of cooking. Out of the simplest and often the most seemingly incompatible ingredients and spices, using either tried-and-true recipes, or concocting something at the spur of the moment, one turns out forgettable or memorable dishes. All that’s left for the poet to do is garnish his poems with a little parsley and serve them to poetry gourmets.