As an exhibition, the New Museum Triennial is still so young that it seems almost premature to call it a New York institution. Yet in just its second iteration, “The Ungovernables,” which runs through April 22, the show has already established the very thing that even veteran surveys of contemporary art would envy: a clear identity, and one that doesn’t seem redundant with either the concurrently running Whitney Biennial –the sprawling, uptown event whose intense emphasis this year on time-based media such as film, music, and performance makes it the antithesis of the compact New Museum exhibition—or the various other museum-sponsored roundups like PS 1/MoMA’s “Greater New York.” Focusing especially on work made by very young artists––the first Triennial went by the asinine name of “Younger than Jesus”––many of whom are based outside the US and Europe, the exhibition brings a surprisingly underrepresented perspective on recent art, no easy achievement in a city with a gamut of commercial galleries and museums. The current show also tries to make a case for reading the work on view amid the political upheaval and messy, unfinished pursuit of democracy that has marked much of the developing world, but the artists don’t fit into this frame as snugly as the curators want to suggest.

The exhibition includes work by thirty-four artists or collectives, few of whom have previously been seen in New York. A large majority hail from countries other than the United States, with a preponderance of Latin American, Middle Eastern, and Asian artists. Curator Eungie Joo has emphasized the fact that many come from countries whose post-1970s existence—a span during which most of these artists were born—was marked by economic and political uncertainty: they were ungovernable in the pejorative, failed-state sense. But she also wants to underline the creative resistance and flexibility of young artists, in which she hears spiritual echoes of the ANC’s embrace of “ungovernability” as a political strategy against apartheid (the term was coined with the Soweto riots and the call to make South Africa positively ungovernable). In the catalog accompanying the show, Joo links the idea to continuing democracy movements across the globe, from the Arab Spring to the Occupy demonstrations.

Political grandiosity aside, such nebulous concepts give a rather misleading picture of the actual proceedings. (The few works that are recognizably political, like Cinthia Marcelle and Tiago Mata Machado’s video O Século [The Century], which shows an empty lot being filled with tossed garbage cans, tires, and breaking glass as if from on offscreen army of rioters, are overwhelmed in number by those that seem to have almost nothing to do with popular resistance or oppression.) What could “ungovernability” mean when applied equally to a young sculptor from neo-liberal Buenos Aires whose towering sculpture is generically detached from anything resembling South American realities, a performance-based artist from Helsinki (who has documented the Bartleby-like experience of interning at a Finnish financial firm and doing precisely nothing on the job), and a sound artist from Cairo who has made a film and piece of music that are as effective as artworks for what they refuse to make explicit about the social landscape of Egypt as for what they reveal?

From a title like “The Ungovernables,” one might further expect a willfully chaotic installation. In fact, the work on view finds an admirable coherence as an exhibition, with various other threads connecting disparate art in a range of media. The Triennial is a tidy, clean, professional-looking affair, much less rowdy than the average international biennial, and despite an admirable number of far-flung return addresses, much of it seems almost domesticated by the rigid floor plan of the New Museum itself: The Bowery building is as unforgiving to curators as is the famously difficult bays of the older Guggenheim, and—with one strong exception here—allows little room to stage the dramatic encounters between works that might be possible in a more flexible space. The art is tucked away in corners when it isn’t snugly installed in what seems a preordained plan. (Rarely do you stop to ask yourself why a particular work ended up where it did, and what this might reveal of the curatorial gambit; you simply accept that there was just no other way to lay out the show.) To be fair, a handful of Triennial artists, like the Bogatá-based Nicolás Paris, who is collaborating with the New Museum staff, city high school teachers, and groups of students to develop new youth programs for the museum, are doing projects off-site, which extending the scope of the show beyond the Bowery building proper.

Advertisement

A better name for the show might have been “Unmonumental,” had the New Museum not used that title for an exhibition of sculpture back in 2007. Much of the most interesting gestures in “The Ungovernables” toy in one way or another with the idea of monumentality, whether by addressing scale or by nodding to the historically deflated form of commemorative public sculpture. The six sheets of thin, hammered copper that the Vietnamese-born Berlin-based artist Danh Võ has causally sprawled on the floor or leaned against the New Museum’s fourth floor walls are fragmentary components of the replica shell of the Statue of Liberty he had fabricated in China. His work seems less like a monument yanked off its pedestal than an ambiguous dressing down of Lady Liberty. In its ambivalent approach to a piece of public sculpture overloaded with symbolic meaning, Võ’s crippled, scattered statue exemplifies a good bit of the work in the Triennial. Nearby, the Argentine artist Adrián Villar Rojas’s gargantuan sculpture A Person Loved Me reaches all the way to the rafters, its upward thrust seemingly arrested only by the physical limitations of the boxy, high-ceilinged space. Constructed of clay, which provocatively undermines the work’s futuristic, vaguely Space Invaders form with a weathered, decaying look, the sculpture is equal parts sci-fi fantasy and industrial relic. These two large-scale takes on the monument sit uneasily with each other, but as they jostle for the viewer’s attention, a kind of unspoken dialogue between them emerges.

Most of the artists do not aim for Võ and Villar Roja’s scale, but many exploit in similar ways the tension between public life and personal, sometimes hermetic meaning. Iman Issa’s four works, three of them on luminously white plinths, include one titled Material for a sculpture representing a monument erected in the spirit of defiance of a larger power. In it, a deeply veined mahogany obelisk a few feet tall is set on its side, the familiar commemoratory form transformed into a slick and beautiful slab of wood. The Cairo-born Issa’s other three “proposed” sculptures, as their titles designate them, include chic tokens of high-modernist design (an angular piece of brass that looks like it might have been pilfered from a Paul McCobb credenza, a glowing dome-glass light shade atop a dark walnut table) alongside texts that restate their titles and in doing so reframe the works as deadpan monuments that will never be built.

In the lobby, the Colombian artist Gabriel Sierra’s sculptures disappear into themselves—the materials that he apparently used to realize his sculptures (a ladder, a folding table, a level, and a 2 x 4) have been imbedded in form-fitting slits cut deep into in the wall, with only a trace of his artistic means of production, as it were, remaining. Pratchaya Phinthong’s tidy stack of 5,000 Euros’ worth of grossly inflated and now obsolete Zimbabwean paper money is no less demure than Sierra’s contribution. A sort of African version of Ron Paul’s worst hyperinflationary nightmare (the dominations include 50 trillion dollar bills), Phinthong’s sculpture is oddly small relative to the absurd number of Zimbabwean dollars it is made from. A memorial to a failed economy needn’t be very large to be monumental.

In her press release, Joo puts an emphasis on the extent to which the work included in “The Ungovernables” is contingent on the experience of growing up in “the aftermath of the independence and revolutionary movements that promised to topple Western colonialism.” More often than not, these upheavals led to new kinds of authoritarianism and economic crisis rather than fully realized liberal societies, and Joo claims that the artists manifest a shared sense of “remarkable pragmatism” in the face of their “bleak inheritance.” In the setting of large survey exhibitions, the word “contingency,” along with other terms like “provisional” and “site-specific,” functions as a curatorial dog whistle for a certain kind of hit-and-run art, one that combines an almost by-the-numbers distrust of the authority of the museum and a demonstrative allergy to churning out goods for the market. Here—at least to judge by the art works themselves, and lacking much to go by as far as the artist’s youthful biographies can tell us—the artists seem to embrace these ideas with less defensiveness or self-consciousness than usual. Even the show’s most anchored works seem designed for the moment. You might never suspect that the huge sculpture of Villár Rojas—the closest thing to a rising star and marquee-ready artist on view at the New Museum—is destined for the dump once the exhibition has closed, but it is, as is the work he is realizing for the World Finanicial Center.

Advertisement

Anyone who visits a lot of exhibitions like the Triennial knows how hard it is to find work that seems both decisive and of its moment, tied to the occasion but also somehow gesturing past it. Joo and her artists have done an excellent job of engaging those twin aims, often turning tenuousness into a buoyant strength. Take Argentine artist Amalia Pica’s arrangement of drinking glasses mounted on a wall (Eavesdropping). What looks at first like an overly thought out one-liner becomes something different when the viewer takes in the strangely humble nature of the glassware, which I guess were scavenged from the leftovers at one of the nearby Bowery restaurant supply stores (the text on one of the glasses reads “Victoria’s Forty & Fabulous! 8/8/09”). The work’s not one for the ages, but it subtly and effectively turns a reflection on political themes of surveillance and exposure into something both local and strangely everyday, even banal.

Other works use quotidian materials to similarly strong effect. Canadian artist Julia Dault’s sculptures of bundled sheets of Plexiglas, Formica, and Tambour were executed on site, with the labor that went into rolling these unwieldy materials and binding them with fat black belt-like straps reflected in their fragile final form. Cinthia Marcelle’s ridiculously simple sculpture of a bucket surrounded by a real, muddy puddle of dirty water is obliquely arresting (and oddly comical) in a likewise hard-to-figure way. On the top floor of the museum, Brazilian artist Jonathas de Anrade’s installation of the pages of a diary from the 1970s found in a trash can in his native Recife, interspersed with period vacation snapshots and architectural photography of the coastal city, drops the viewer into a running commentary on the everyday from a perspective that seems achingly personal and archly anonymous at the same time.

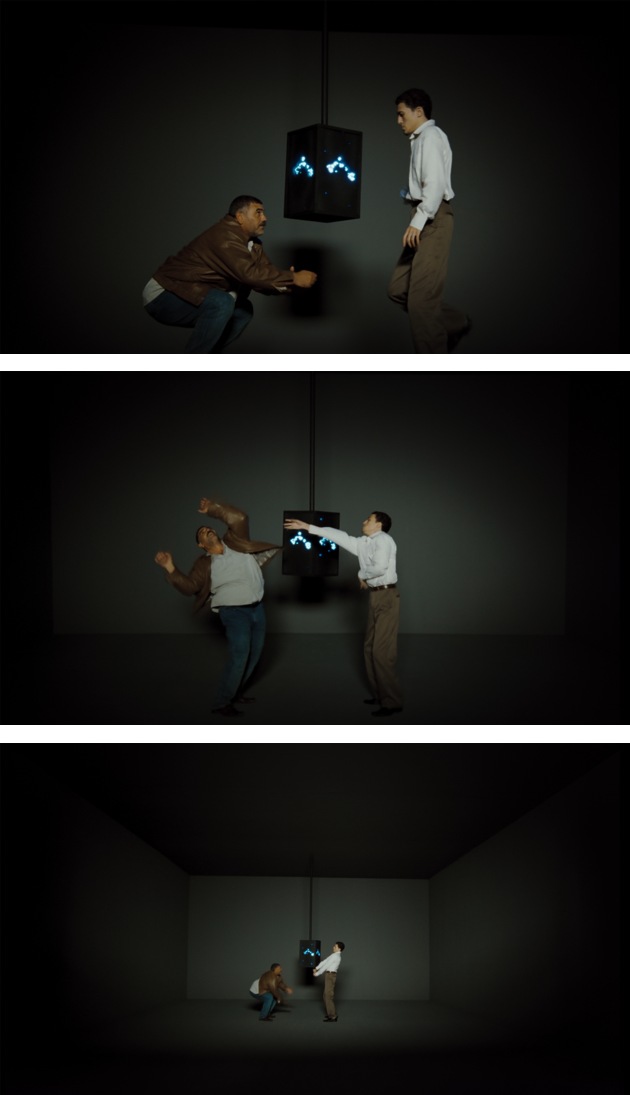

The work that leaves the most visceral sense of local realities transformed by their transport to New York is Egyptian artist Hassam Khan’s remarkable 35-mm six-and-half-minute looped film JEWEL. Best known for his sound art, Khan here has shot two men dancing in a dimly lit space on either side of a bejeweled revolving speaker that blasts infectious Cairene street music (incidentally composed by the artist himself). Installed in what at first looks like the dreaded black-box format—the bane of any number of biennials—the dark interior of the viewing room in fact mirrors the film’s set, a fact that only gradually becomes apparent. The two dancers in JEWEL are hardly mirrors of each other, though—the slender man on the right wears a crisp white shirt and tan office slacks, the chunky fellow on the left has a tan leather jacket, an untucked shirt that hangs over his belly, and jeans.

Were these two guys plunked at random off the Cairo street? What is the relationship between them? Whatever the answer, their dance moves are fantastic to watch, solo improvisations to the soundtrack. As the film progresses, the camera slowly pulls further and further back from the duo, who grow smaller and smaller like little music-box figures while the music booms forth just as loudly. Like much of the work on view in “The Ungovernables,” there’s a public space being represented by JEWEL, but one whose meaning is only fleetingly apparent.