Simone Weil once wrote that “nothing of all that the peoples of Europe have produced is worth the first known poem to have appeared among them.” She was referring to the Iliad, and, judging by the recent raft of translations, adaptations, and novelizations of the poem, we would seem to agree. Four new English versions, all published within a few months of each other, enter a market already glutted with Iliads, many of them—like Richmond Lattimore’s recently reissued classic 1951 translation and Robert Fagles’s widely used 1991 rendering—still vital. Now, the New York Theatre Workshop has staged An Iliad (up through April 1), a play that compresses the entire epic into a one-man, hundred-minute performance.

While translations abound, dramatizations of the Iliad are fairly uncommon. Of course the poem has inspired countless plays—Aeschylus, for instance, called his tragedies “scraps from Homer’s banquet.” But these typically focus on a single episode, like the Greeks’ efforts to persuade Achilles to return to battle in Book 9. The entirety of Homer’s text runs to over 15,600 lines and would take about 24 hours to recite from beginning to end; it also has hundreds of characters—men, women, gods, demigods, a crying baby, and two immortal, talking horses, among others. Remarkably, An Iliad’s ultra-condensed script—co-written by the actor Denis O’Hare and the theater director Lisa Peterson—not only attempts to encompass almost all of this, but it also places that burden on a single character.

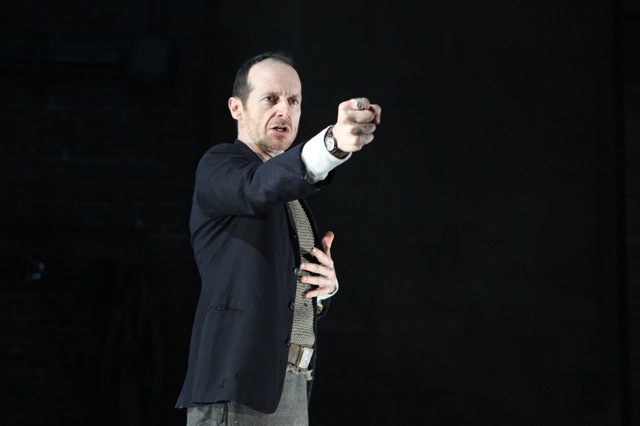

That character is The Poet—a fictional figure, mysterious, and slightly bedraggled, who, we learn, was present at Troy during the war and has been telling the story ever since. Portrayed on alternate nights by Tony-award winners O’Hare and Stephen Spinella, this lone figure is accompanied by Brian Ellingsen on bass, who, playing a haunting score composed by Mark Bennett, stands in for the voices of the muses, who provide periodic inspiration to The Poet. As his goddesses sing to him, he stalks up and down the stage paraphrasing the events of the poem, portraying the characters themselves, and, in heightened moments, quoting directly from Fagles’ translation. Like the poem itself, the set, designed by Rachel Hauck, has here been radically stripped down—there is little else besides a pair of large metal doors meant to evoke Troy’s Scaean Gates, the main entrance to the city in front of which Achilles is fated to die.

The play, according to O’Hare, had its origins around 2005, during the height of the Iraq war. A committed pacifist, O’Hare said he was drawn to the way the poem grappled with “war and its meaning, and the waste of war and the human propensity for violence.” Lisa Peterson, for her part, was more attracted to the Iliad’s oral history—the possibility that during pre-literate times a guild of itinerant rhapsodes, something like ancient Greek troubadours, preserved the poem through recitation until it could be set down in writing (Athenian sources suggest this had happened by the sixth century BC). Fascinated by the idea that these rhapsodes, relying in part on improvisation, each produced different versions of the poem, she calls An Iliad “our attempt to imagine what it would be like to hear one of those bards.”

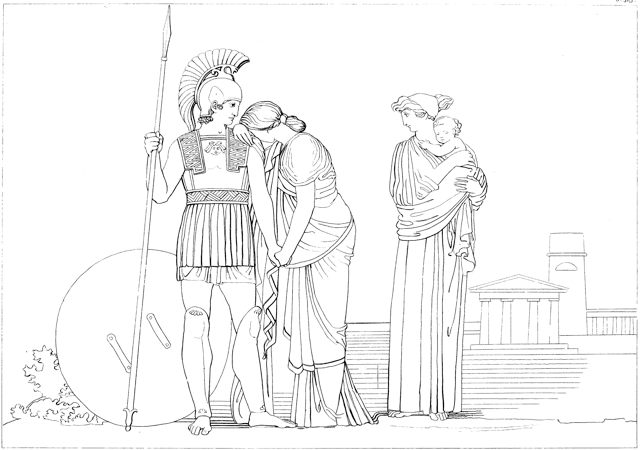

By focusing primarily on the conflict between the Trojan prince Hector and the Greek hero Achilles, the two have adroitly condensed the poem into something that takes little more than an hour and a half to perform; though pared down, the play still manages to give at least some sense of what has made the story so broadly appealing for the past 2800 years—among other things, that the author of the poem is, as Weil called him, “impartial as sunlight.” Consider the play’s rendition of the famous scene from Book 6, in which Hector rushes home from the battlefield and meets his wife, Andromache, and their son Astyanax, on the walls of Troy. The scene in the poem is brief but touching—Hector reaches for his son, who cries, frightened by his father’s helmet and its plume of horse hair. The parents laugh at their child, and Hector removes his helmet and takes his son up, praying aloud that he will become an even greater soldier than his father (tragically unaware that within a few weeks he and his son will be dead, and his wife enslaved).

In their separate performances, both O’Hare and Spinella impressively managed the lightning transitions between Hector, Andromache, The Poet, and even the crying Astyanax, giving each character an appropriate and distinct tone—Hector proud and booming, Andromache wryly mocking but full of concern for her husband. In his unselfconscious immersion into the scene, O’Hare was the more convincing;

Spinella’s rendition, though admirable, suffered from his inclination to over-exploit the dramaturgical absurdity of the situation for comic effect. Still, both performances captured some of the overwhelming sense of warmth and sympathy present in Homer’s original, and demonstrated why, reading the Iliad, “one is barely aware that the poet is a Greek and not a Trojan.” Hector and Andromache are, after all, the poem’s ostensible antagonists.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, these moving interludes are relatively rare. One problem is that O’Hare and Peterson, in an apparent effort to make the story accessible, have written much of the script in chatty and insipid language that they attempt to elevate from time to time with awkwardly interposed quotations from Fagles’ austere translation. Here, for instance, is how the play opens:

RAGE!

Goddess, Sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles,

murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses,

hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls,

great fighters’ souls, but made their bodies carrion,

feasts for the dogs and birds…What drove them to fight with such a fury?

Ohhhh…the gods, of course…um…pride, honor, jealousy…Aphrodite… some game or other, an apple, Helen being more beautiful than somebody—it doesn’t matter. The point is, Helen’s been stolen, and the Greeks have to get her back.

Huhhh. It’s always something, isn’t it?

This hardly seems necessary. O’Hare and Peterson’s reluctance to build their script primarily from Fagles’ translation is understandable: though lovely, it is probably too complex to be recited to an audience unfamiliar with the play, and its relentless iambs tend, when read aloud, to have a soporific effect. But many others have succeeded in rendering the Iliad in language that was at once jarringly modern and easily understood, without resorting to such contrivances. Take Christopher Logue’s fragmentary adaptations—published between 1963 and 2005 and initially designed to be read aloud as part of a BBC production—which Garry Wills called the best English version since Chapman’s 1598 translation.

O’Hare and Peterson might also have taken some inspiration from Memorial, the remarkable new interpretation of the Iliad by the British poet and classicist Alice Oswald. In this short volume of verse, Oswald attempts to convey an aspect of the poem that she feels is often ignored—its enargeia, “which,” she writes, “means something like ‘bright unbearable reality.’ It’s the word used when the gods come to earth not in disguise but as themselves.” Like O’Hare and Peterson, she attempts to capture the Iliad’s relentless depiction of the waste of war. She does this by gutting the entire Trojan War narrative—no stolen brides, no quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon—leaving behind only Homer’s pastoral similes and biographies of the hundreds of soldiers slain. The first eight pages of Oswald’s text list the names of those killed, Greeks and Trojans alike, in all capital letters—a searingly stark tribute to the dead reminiscent of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall. The rest of the poem takes the simple format of the record of a soldier’s death and his brief biography followed by a simile—often repeated—in antiphonal response.

ADRESTUS and AMPHIUS

Everyone knew they were going to die

They were the sons of Merops the prophet

He begged them to stay home but they couldn’t listen

Their own ghosts were calling them to Troy

Immaculate in clean linen

They set out together but Death

Was already walking to meet themLike a goatherd stands on a rock

And sees a cloud blowing towards him

A black block of rain coming closer over the sea

Pushing a ripple of wind inland

He shivers and drives his flocks into a cave for shelter

The cumulative effect of these scenes and similes, one after another, is disquieting, and not only for the emphasis they bring on the mass of slaughter contained in the Iliad. Still more strikingly, for perhaps the first time in English, these battle passages, which too often breeze by in a monotonous blur of gore, have been turned into real poetry. Oswald forces us to look closely at the carnage, and in doing this, quite faithfully captures an essential aspect of the poem in language that is nevertheless powerful and affecting. This should be the goal of any good translation. That the Iliad is still capable of prompting works as moving as Oswald’s gives us some hint as to why, for millennia, we have returned so often to this poem, endlessly excavating it in search of answers to the same questions that have confronted us since it was first sung around a campfire somewhere in antiquity.

Advertisement