“Every aesthete in New York, Paris, and London wants to make a musical,” film critic Andrew Sarris joked at the height of French New Wave. As the Vietnam War escalated, one could have made a parallel assumption about another popular genre: Every Marxist intellectual wants to write a Western. The most notable was Franco Solinas (1927–1982), a teenaged partisan and longtime member of the Italian Communist Party, journalist for the Communist newspaper L’Unità, and author of Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano, Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers, and Costa Gavras’s State of Siege (to name a few). Solinas worked on four Spaghetti Westerns—all included in a three-week-long series at New York’s Film Forum that begins June 1—contributing to this wildly commercial and equally disreputable mode as decisively as director Sergio Leone or composer Ennio Morricone.

A reader of Fanon (for the colonized, “having a gun is the only chance he still has of giving a meaning to his death”), as well as Gramsci (“to many common people the baroque and the operatic appear as an extraordinarily fascinating way of feeling and acting”), Solinas invented what might be termed the Third World Western. Around the time he wrote The Battle of Algiers, a near-newsreel representation of the conflict between European colonizers and the colonized wretched of the earth, he provided the treatment for Sergio Sollima’s The Big Gundown (1966). Lee Van Cleef, who had just played the villain in Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), was here cast as an implacable yet idealistic bounty-hunter, poised to run for the US Senate, when he is recruited by the railroad magnate who is sponsoring him to hunt down “Cuchillo” Sanchez, a Mexican peon accused of raping and murdering a 12-year-old girl.

Déclassé, outlandish, and brutal, The Big Gundown has the standard Spaghetti Western virtues; its originality lay in making its true protagonist the fugitive. The irrepressible Cuchillo (played by Tomas Milian) turns out to be a disillusioned supporter of Benito Juarez with a class analysis (he is in fact an innocent witness to the crime). Van Cleef’s character realizes that he is the tool of ruthless plutocrats and capitalist running dogs. Thus, Solinas would use the Western as an arena in which to play out the struggle dramatized in The Battle of Algiers. “Political films are useful on the one hand if they contain a correct analysis of reality and on the other if they are made in such a way to have that analysis reach the largest possible audience,” he told an interviewer in 1967.

Solinas’s screenplays were not the first un-American Westerns. The Italian-made productions that made Clint Eastwood an international star were universal in their appeal to audience ressentiment, bloodlust, and inchoate desire for vengeance. (At the same time, they were an eminently disposable product. “This is the most difficult series I’ve ever put together,” Film Forum programmer Bruce Goldstein told The Wall Street Journal, detailing his search for usable prints.) But in turning the most American of movie genres into a subversive commentary on American Cold War politics, Spaghetti Westerns elaborated an existing tradition.

The highly popular Broken Arrow (1950), notable for preaching peaceful coexistence between white settlers and their Apache neighbors, was written by (but not credited to) blacklisted red Albert Maltz; released the same year, The Devil’s Doorway, a less commercially successful but more militant brief on behalf of a mistreated Shoshone cavalryman, was written by Guy Trosper (designated a fellow traveler by the FBI) and, unlike Broken Arrow, praised for its political perspicuity by the Daily Worker, which recognized it as an allegory on the situation of African American veterans.

Addressing another aspect of the American West, two blacklisted Communists, Lester Cole and Marguerite Roberts, worked at various times on the script for the long-germinating Viva Zapata!, set during the early-twentieth-century Mexican Revolution and celebrating the radical agrarian reformer Emiliano Zapata—although it was ultimately directed, from John Steinbeck’s screenplay, by a former Communist desperate to avoid the blacklist, Elia Kazan. Kazan strenuously promoted Viva Zapata! as an anti-Communist movie until the late ‘60s when he saw it as having a special significance for “disgruntled and rebellious people” throughout the world—a proto–Spaghetti Western.

By then, the Communist bloc was producing its own red Westerns. The international success of The Magnificent Seven (1960), also set in Mexico and the original example of what cultural historian Richard Slotkin termed the “counter-insurgency scenario,” is credited with inspiring a cycle of Soviet features. These crypto-Westerns featured Bolshevik civilizers pacifying the primitive Muslim regions of Central Asia—a Soviet wild east. At the same time, in part to counter the series of Karl May adaptations that were the most popular West German movies of the 1960s, the East Germans developed the Indianerfilme.

Advertisement

Sons of the Great Bear, adapted in 1966 from a children’s novel by the Communist anthropologist Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich, established the template: Indian tribes, usually led by the Yugoslav bodybuilder Gojko Mitic, struggle against various combinations of avaricious settlers, mendacious military officers, corrupt lawmen, and rapacious imperialists. Populated by greedy seekers of lebensraum and loot, as well as whip-cracking martinets shouting in German at their presumed racial inferiors (often played by Slavs), these movies have an unintended subtext. Still, there is no missing that the forward march of history is embodied by enlightened Native Americans. In one movie, Mitic calls upon “Indians of all lands” to unite; in another he announces a domestic program based on farming, animal husbandry, and light manufacturing.

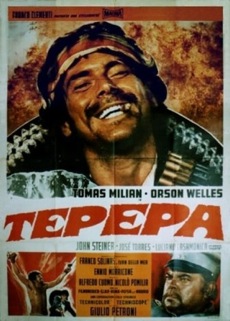

Solinas’s Westerns resembled none of these, except perhaps as critiques of Viva Zapata!—the 1910–1920 Mexican Revolution being his main historical marker. He went deeper into the Mexican revolution with A Bullet for the General (1966), The Mercenary (1968), and Tepepa (1969) all of which told essentially the same story of European or North American freebooters who throw in their lot with revolutionary bandits. The premise is somewhat diluted in The Mercenary, directed by Sergio Corbucci, in which the protagonist pragmatically switches teams, abandoning the sleazy representative of Porfiro Diaz’s cruel military dictatorship for a more sympathetic if unstable rebel (despite his distaste for the bandit’s ultra-left mistress).

A Bullet for the General and Tepepa are less ambiguous in siding with social banditry and peasant revolt, however problematic that may be. Vengeance is collectivized. Both movies end by extolling the therapeutic aspect of Third World violence that, per Fanon, liberated “the native from his inferiority complex” and feelings of despair. US interventionism is embodied in A Bullet for the General by a CIA agent avant la lettre whose civilized cool effectively hypnotizes the unsophisticated revolutionary. Tepepa, which has Milian’s ripest performance as the eponymous guerrilla leader (and features Orson Welles as a Porfirista commandant) further complicates the scenario. No less than the revolutionary cadre in The Battle of Algiers, the illiterate rebel makes expert use of explosives and it is not the gringo interventionist (here a thin-lipped, half-mad British doctor) who betrays him so much as the foolishly accomodationist leader of the Mexican revolution, Francisco Madero.

Solinas’s example successfully politicized the Spaghetti Western. Carlo Lizzani’s Requiescant (1967) cast Pier Paolo Pasolini as a revolutionary priest. Sollima revived the Cuchillo character in his 1969 Run, Man, Run—an honest rogue who steals but ultimately returns gold used to finance the Mexican revolution—and, in a sort of autocritique, starred Milian in the 1970 Face to Face as a social bandit who fascinates a fanatical professor of history. In the aftermath of Italy’s “hot autumn,” Corbucci’s Compañeros (1970) features militant leftwing students, as well as villainous American whose pet eagle feeds on dead Mexicans. Even Leone’s last Western, known in English as Duck You Sucker! (1970), began with a facetious quote from Chairman Mao. (All of these, save Run, Man, Run are included in the Film Forum series.)

Solinas also impressed Hollywood’s most radical director of Westerns, Sam Peckinpah—although the lineage of The Wild Bunch (1969) can, along with that of the Spaghetti Western and also The Magnificent Seven, be traced back to Akira Kurosawa’s samurai films. Still, Peckinpah commissioned Solinas to write a screenplay known in English as Life is Like a Train that was never produced and save for a few stray references seems to have been lost to history.

The series “Spaghetti Westerns” is showing at New York’s Film Forum from June 1 to June 21.